The launch of European Women’s Rowing Championships in 1954, sanctioned by FISA, demonstrated institutional anxieties around the women’s sport, even as it introduced an important new competitive destination for female athletes.

The launch of the first European Rowing Championships for women, held in Amsterdam in 1954, was a milestone in the women’s sport.

For female rowers in Britain, this was not to be their first taste of international competition: clubs had occasionally competed in locations from France to Poland and Australia in the 1930s and late 1940s, and at the three International Women’s Regattas which immediately preceded the European championships.

- On tour in 1938- Eleanor Lester and her crew race in Sydney © River & Rowing Museum

- The crew find time to meet some koalas © River & Rowing Museum

Crucially though, the European Championships would be the first women’s event sanctioned by FISA (the Fédération Internationale des Sociétés d’Aviron), and as such required the sport’s governing body to endorse the competing crews. The Amateur Rowing Association was thus compelled to do so, and so this event can also be seen to have triggered the eventual integration of the Women’s Amateur Rowing Association into the ARA in 1963 – an important step in domestic administration of the sport.

The 1954 championships followed a lengthy campaign from various European countries to provide women’s events. Foremost in these campaigns was France, who had long pressed for inclusion, and took the opportunity to launch an International Women’s Regatta the day before opening the 1951 European Championships – at this point still solely a men’s event – in Macon.

- 1951- The British women relax after racing at Macon © River & Rowing Museum

A key aim of the International Women’s Regatta was to ‘give proof of the standard of women’s rowing in Europe and show the strengths of their claims for the inclusion of women’s events’ (H. B. Freestone, WARA Honorary Secretary, in Rowing, Summer 1951). Four countries competed in this 1951 regatta: Holland, Denmark, Great Britain and of course, France; and more countries would join this cohort for the regatta in following years, most notably in 1953 when Norway, Finland, Poland, Austria and Germany were also competing.

France was committed the success of this event, investing in visiting teams at both financial and human levels. One official of the FFSA (Fédération Française des Sociétés d’Aviron), Mademoiselle Antoinette Rocheux, and one Mrs. Suzanne Caverhill (a Frenchwoman who married a Scotsman – hence the surname), are credited in particular with providing the British women with hospitality and some help with their air fares for the 1951 regatta. The report from the women’s team is overwhelmingly positive, and the opportunity to mix with the men’s team presented as a novel and mutually enjoyable consequence of the event.

Domestic camaraderie apart, the British women reported their amazement at the extent of their integration into the championships:

The various men’s crews were, of course, practising daily for the European Championships, and it gave us a sense of some importance to find that we – mere women – had some place in this centre of bustling rowing activity[…] It really was wonderful while it lasted. (Irene Helps, in Rowing, Autumn 1951)

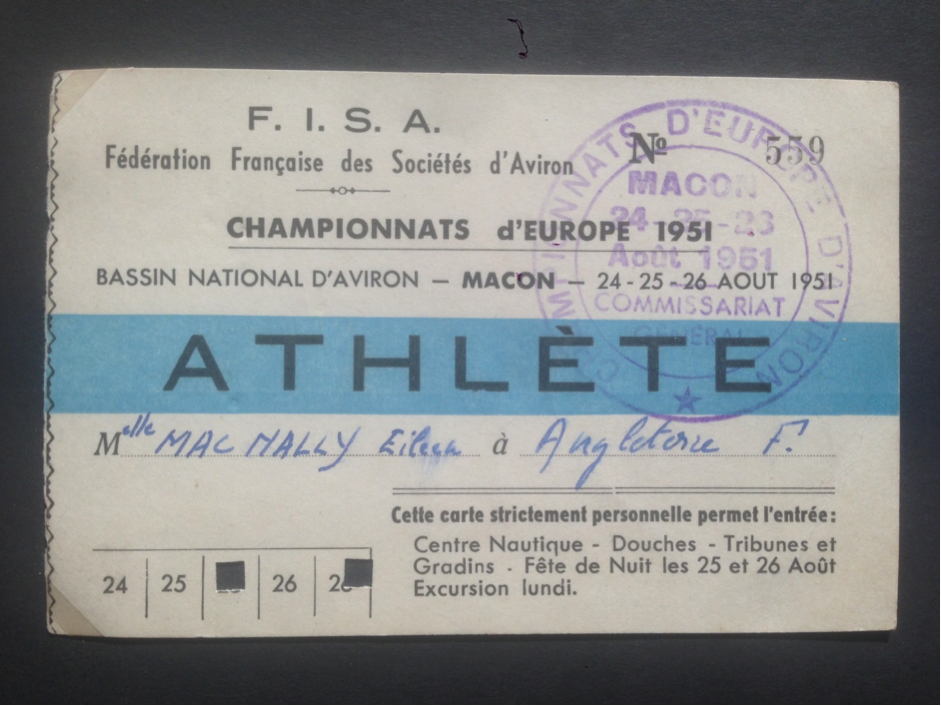

A further point made in the same report regards the status conferred by competition: ‘We shall always remember the little printed cards on which we were described as ‘Athlete’ and which seemed to open any door’. The contrast between the rowing cultures of France and Britain with regard to gender is marked.

- Athlete badge belonging to Eileen MacNally, one of the British women competing at Macon

In 1952, the women’s team enjoyed their first international regatta win in the eight at Amsterdam. The timing of this, in the run-up to the Helsinki Olympics, leads Rowing magazine to report that while women did not yet race at the Olympics, ‘they have done their best to earn the right to’ (Rowing, Summer 1952): the influence of success on the British rowing community in terms of the legitimacy of the women’s team is significant. Alongside this athletic endorsement, the femininity of the team is highlighted, with the report that on hearing the national anthem following their win, ‘true to their sex, they thought it right to shed a tear’.

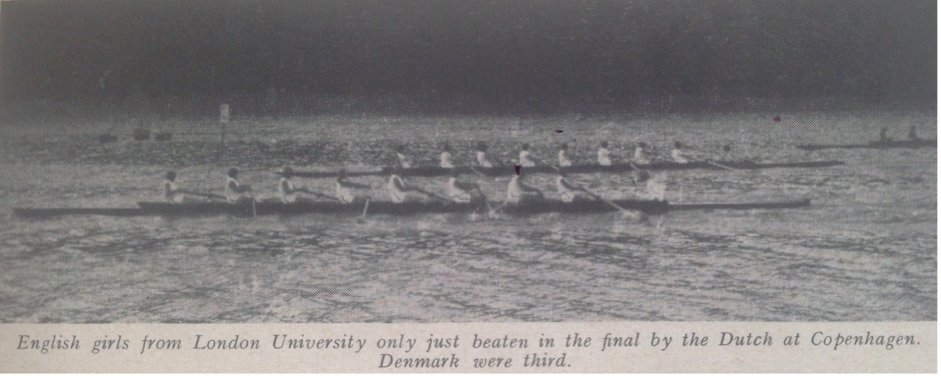

After the 1953 International Women’s Regatta, where the British eight came a very close second to the Dutch team, a Danish representative began calling for more formalised administration for the international women’s sport. The advent of women’s events at the European Championships in 1954 was awaited with some expectation.

- A close call- The women’s eights final at the 1953 International Women’s Regatta

Yet only four months before the 1954 championships, FISA displays what Rowing magazine describes as an ‘extraordinary attitude’, declaring that ‘the spectacle of young women in rowing shorts standing about in the vicinity of the boat tents is distracting to the men’, and that they must therefore race some days before the men, and then leave the venue.

This is not only significant as an indicator of the attitudes of FISA, but as posing a serious logistical problem. Women’s teams would not be able to share transport and resources with the men’s teams – in Britain’s case leading to a huge rise in transport costs and changes in the support team. The ARA is reported to describe this decision as ‘a lot of nonsense’, but as not having any voting power to change it. This approach takes a more exaggerated form in the years that followed, albeit with more notice given: men’s and women’s championships would take place in separate locations, and with some weeks between.

There was one significant benefit of these rulings to the UK, however: it was able to host the women’s championships in 1960 while still lacking the two-kilometre championship course needed for men’s events. Women raced over just one kilometre, and could be well accommodated at the Welsh Harp in Willesden.

Article © Lisa Taylor

- Poster for the 1960 European Women’s Rowing Championships, to be held at the Welsh Harp © River & Rowing Museum

![“And then we were boycotted” <br> New discoveries about the birth of women’s football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 2](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/And-then-we-were-boycotted-New-discoveries-about-the-birth-of-womens-football-in-Italy-1933-Part-2-by-Marco-Giani-440x264.jpg)

Fortunately, in the 30-year history of the Women’s European Rowing Championships, on the ten occasions when there were both women’s and men’s European Rowing Championships in the same year (there were none for men when it was an Olympics or World Championships year, of course, as was the case in 1960 when the Women’s Championships were on the 1,000m-long Welsh Harp reservoir) the women’s and men’s events were actually only in different locations twice (in 1955 and 1963). On the eight occasions when they were in the same place there were just a few days in between to allow the swapping of one set of boats for another, removal of the 1,000m start and practice for the men on the course.

Indeed. I haven’t seen primary evidence relating to the decision-making process within FISA on this issue as yet but it’s interesting that practicality seems to have prevailed after the original drive for separation. Willesden is itself a fascinating case and merits much more time than my brief allusion above; it seems to be a very specific combination of circumstances that led to hosting the 1960 event, not least being in an Olympic year as you say. Look forward to discussing this more in time!