- The Washington Belles, 1911

Basketball was subject to racial segregation from the 1890s until partial integration of the National Basketball League (NBL) in the 1940s and the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 1950. For African American women, ‘Black Fives’ basketball presented them with barrier’s not only based upon their ethnicity but also their gender. However, black women’s teams were still able to flourish and grow post-1910, ironically because of their isolation from a white culture that refused to treat African Americans with equity. The period, 1904 to 1950 is known as the ‘Black Fives Era’ when African Americans of both sexes created their own teams and organised their own leagues often supported by churches, athletic and social clubs, ‘coloured YMCA’s’, and black-owned businesses and newspapers.

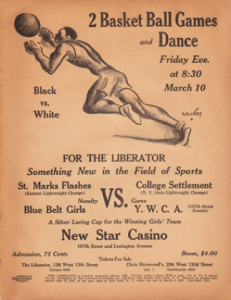

The use of ‘blacks-only’ venues such as dance halls – due to the Jim Crow Laws enforcing racial segregation (from 1877 to the mid-1960s) – provided a safe, profitable and conducive environment for women’s and men’s Black Fives basketball to thrive. The black urban districts of New York, Chicago, Washington and Pittsburg led the way in offering a unique blend of music, dancing and basketball for African Americans. This marriage of leisure activities was a cultural innovation ‘that grew out of necessity, opportunism, timing, and [a] broad cultural awareness by community leaders.’ The first recorded basketball game between two all-black women’s basketball teams – the ‘New York Girls’ and the ‘Jersey Girls’ – took place on 26 February 1910, at Harlem’s Manhattan Casino.

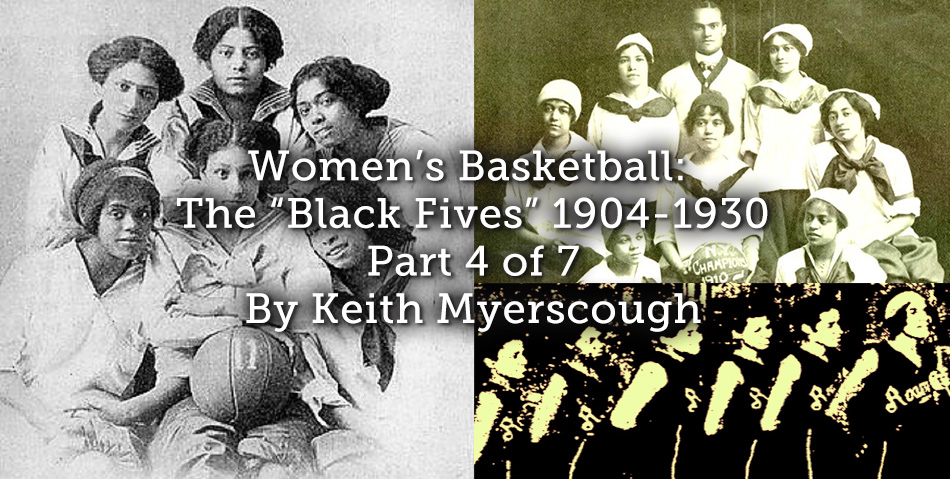

- The New York Girls, 1910-1911

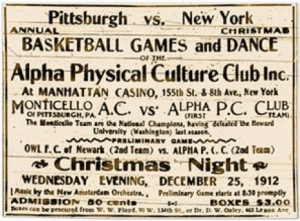

The growth of Black Fives basketball in segregated athletics clubs encouraged female club members to play basketball. By 1910 the popularity of the game in New York had encouraged the growth of basketball not only in female sections of clubs but also in local schools. In 1912, the ‘Smart Set Athletic Club’ of Brooklyn formed a women’s basketball team called the ‘Younger Set’. The team was made up of players from other distinguished teams: Edith Trice, formerly the captain of the ‘Spartan Girls’ of Brooklyn, and Rosa Mitchell, formerly the star player with the ‘New York Girls’. After seven games the Younger Set were undefeated perhaps because they had attracted some of the best players in New York with financial inducements afforded them by playing at Young’s Casino, Harlem.

- Edith Trice, 1913

The introduction of basketball into African American public schools in Washington, DC, was initiated by the ‘Grandfather of Black Basketball’, Dr. Edwin Bancroft Henderson, between 1904 and 1910. The development of Black Fives basketball was not solely reliant upon commercial enterprise and the public schools system; there was a third strand to its growth – the proliferation of local newspaper reports of forthcoming events and match results.

- Ballard HS, Georgia, 1923

The segregation of black players from their white counterparts in all aspects of daily life impacted greatly upon the development of basketball as a multicultural sport for both males and females. Paradoxically, the female game for black players stayed true to Naismith’s original 13 rules at a time when the white-female game was being reinvented by the pioneers of the girl’s game which was designed to represent the social conventions of the day. The black-female game of basketball was able to prosper free of the social conventions determined by the pronouncements of a white Western culture. The isolated growth of Black Fives Basketball benefitted the game in terms of its entertainment value for their black audiences. The flow of the game and its physical demands appealed to the athleticism of black players and spectators.

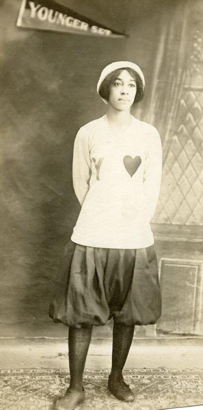

In the 1920s Chicago’s ethnic minority interest in Basketball was maintained by the ‘African-American Basketball League’, which had both male and female divisions. The most successful women’s team was The ‘Roamer Girls’ – they were formed in 1921 from a team at the Grace Presbyterian Church Sunday School. Their exploits were recorded by The Chicago Defender, a local black newspaper who treated the league as a social event for the black urban community. The star player for the ‘Roamer Girls’ was Isadore ‘Izzy’ Channels who was described by the Chicago Defender in one game in 1925, thus: ‘she played the game far above the heads of her opponents and far in advance of her colleagues, registering 19 of the points scored by her team.’

- The Roamer Girls, date unknown

The ‘Roamer Girls’ remained undefeated for 6 seasons. They occasionally played what they called ‘Nordic’ or ‘Lily’ (white) teams in order to give themselves more competitive games. By the late-1920s they were also able to play a growing number of travelling clubs, community teams, and interscholastic league teams from across the nation. Their popularity with the African American population of Chicago is illustrated by a poll of black sporting heroes carried out by the Defender. Nominees could be of either sex but they had to be amateurs. The contest ran from 21 May to the 22 July 1927 with one third of the votes cast going to female athletes who occupied the top four places. Miss Irma Mohr was first with 18,000 votes – she played golf, basketball and tennis; Mrs C O Seames was second with 10,730 votes – she played and organised tennis for African Americans in the Chicago area; in third place came Miss Corrine Robinson with 5,000 votes – she played basketball, ran track and played tennis; and in fourth place came the captain of the Olive Baptist Church basketball team with 1,400 votes. Only two men got more than 1,200 votes. The voting patterns reveal that female participation in sports was popular with the general public who voted in large numbers for the 21 black nominees. The readership of the Defender clearly had a sound knowledge of the nominees exploits, taking the time to cut out the voting coupon from the newspaper and posting it.

The community support African American females received enabled them to participate in a variety of sports, creating a black-female sporting culture – one which acted as a springboard for further developments that chipped away at the culture of segregated basketball in the Black Fives era.

Article © Keith Myerscough