Read the earlier parts of this series

Part 1 – HERE and Part 2 – HERE

The 5 documents images are taken from:

Milano, Archivio di Stato di Milano,

Prefettura di Milano, Gabinetto, Carteggio fino al 1937 – serie I.

These images are published on the permission by Ministero dei Beni e le Attività Culturali.

Any reproduction of images is forbidden.

As we’ve already seen in the first two parts, a male-dominated public archive such as the Prefettura fond of the Milan Archivio di Stato hides some interesting sources for the history of women’s sports: in fact, while these brave women were breaking prejudices on the field, men acting as judges, journalists, sports managers and also the Prefetto were deciding their fate. Often we’re so much influenced by the sexist prejudices we can still read in newspapers and sports magazines, that we tend to forget that women’s sports are also a question of managing power: the male power to decide if the women are permitted to compete.

The façade of Milan Archivio di Stato

The Joan Miro’s sculpture, entitled Mere Ubu, was donated during the 1970s’ by the artist to the Municipality of Milan

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivio_di_Stato_di_Milano .

As SISS historian Sergio Giuntini says his 2017 Storia agonistica, sociale e politica dell’atletica leggera italiana (pp. 99-107), just a year before Mussolini took power with the Marcia su Roma coup d’état (1922), the gymnastic society Pro Patria et Libertate (‘for the Country and the Freedom’), located in Busto Arsizio – an industrial centre between the Maggiore Lake and Milan, near where the International Airport of Malpensa is today – sent some athletes to the first-ever international women’s athletics games, the Olympiades Féminines held in Monte Carlo in late March 1921. The Women’s Olympiad was organized by Alice Milliat in response to the IOC decision not to include female athletes in the upcoming 1924 Olympic Games: France, Italy, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and probably Norway sent their representatives to Monte Carlo – they competed in the gardens of the Casino!

The Wikipedia page about this 1921 Women’s Olympiad [read HERE) says that the number of Italian participants is unknown, and none of them was able to win a medal. Thanks to Giuntini, we know that the women from Busto Arsizio only competed in the events on 25 March 1921, being all eliminated in the preliminary heats. They were all very young (12 to 18-years old), it was their first ever international experience, and they were so naïve with their footwear. They didn’t even know how to start correctly during the running events, because no women in Italy were taught this skill.

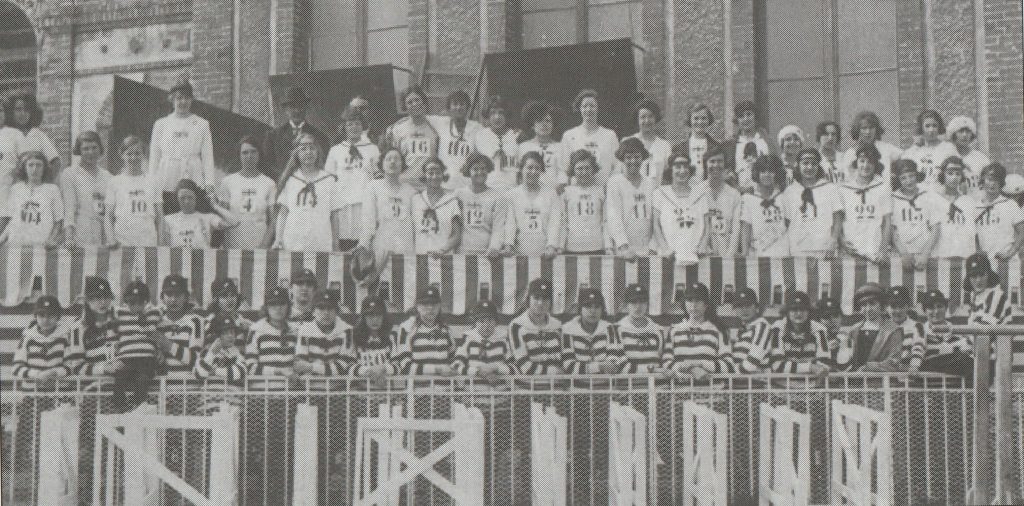

The Italy National Team at the 1921 Olympiad

Note that most athletes are wearing not the traditional light-blue shirt, but rather blue-and-white-striped Pro Patria shirt

Some of them are so young that it would seem reasonable to surmise that they were there only to attend, rather than to compete!

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Maria_Piantanida?uselang=it#/media/File:Piantanida_Olimpiadi_della_Grazia_1921.jpg

The Englishwomen are in the top left section of the group; the Pro Patria athletes are below

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1388529153893339141

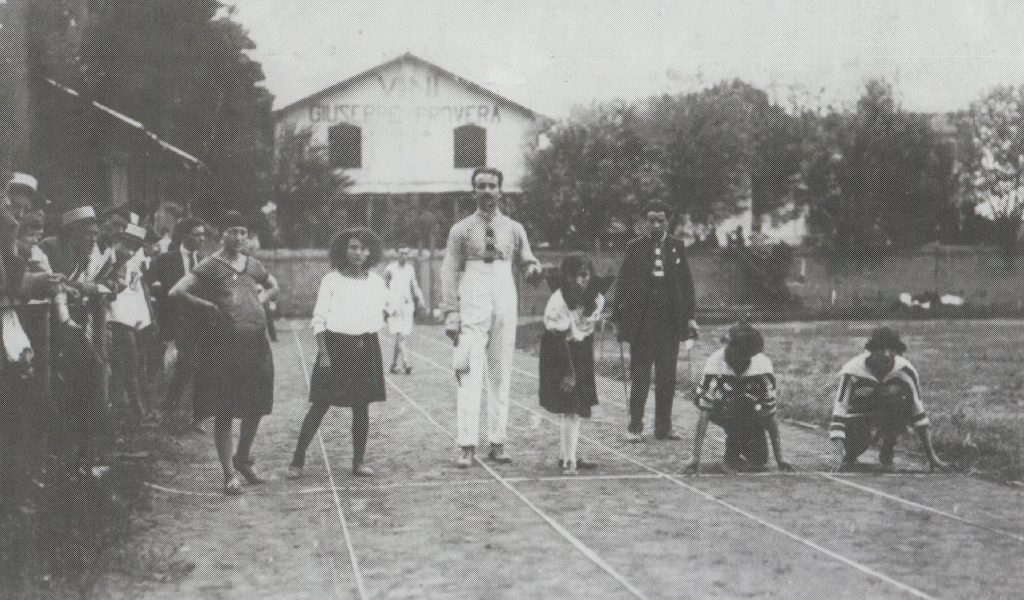

Some weeks later, in Milan, the Pro Patria athletes (on the right) were the only ones able to start properly in this 60m event: had they learnt in Monte carlo?

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1388529153893339141

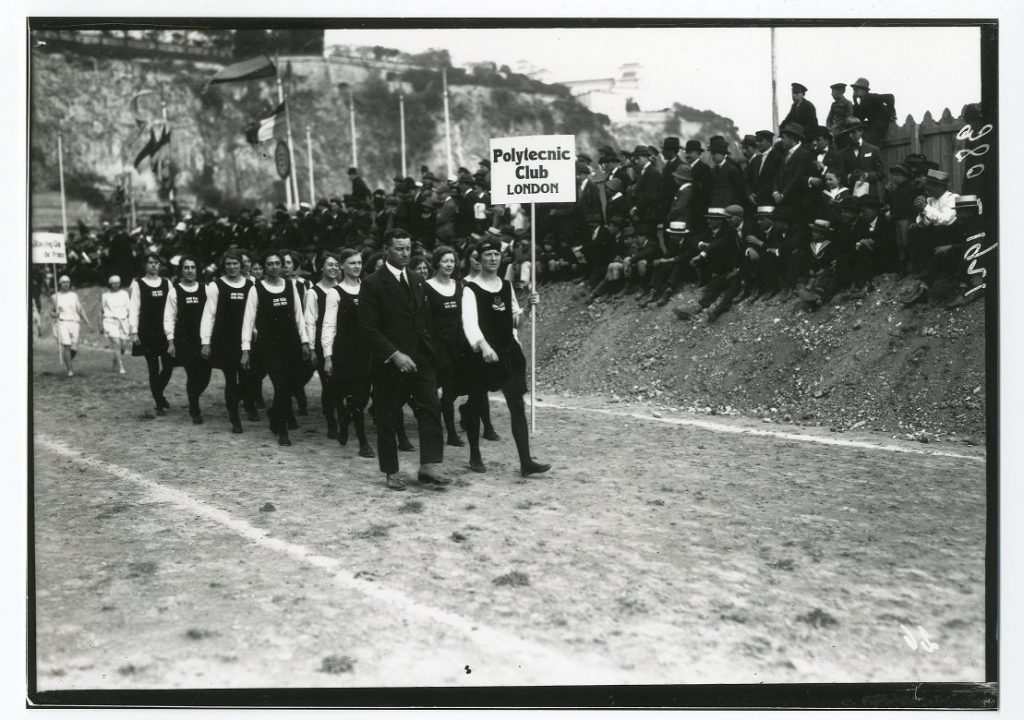

Pro Patria was not the only case of a private sports club competing as the national team, such as this Woolwich & Regent Street Polytechnics athletes photo, taken during the 1921 Olympiad opening ceremony, note both the sign and the British flag on the girls’ uniform.

The English team

Source: https://twitter.com/UoGArchives/status/707169724518555648

Further photos shared on Twitter by the University of Greenwich Archive account tell us more about the “poli girls” … As we’ve already seen in Grazia’s Barcellona’s series (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/flipping-through-grazias-photo-albums-flashbacks-from-the-career-of-a-1940s-1950s-italian-figure-ice-skating-champion-part-1/ ), building up a photo album seems to be the most common way to preserve the memory of sportswomen all over Europe!

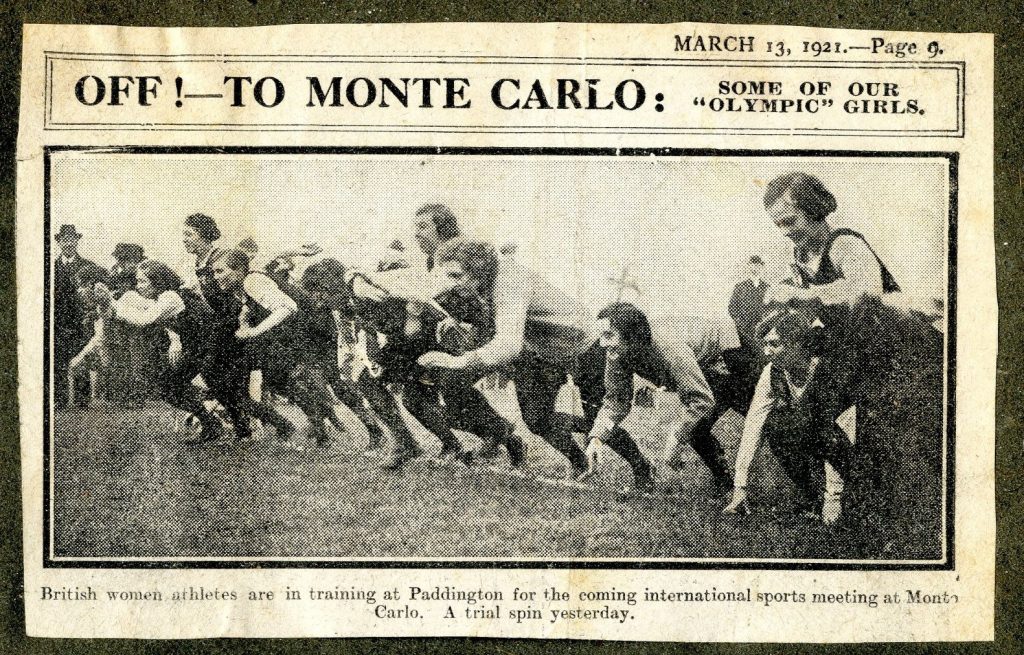

The “poli girls” training in Paddington

Source: https://twitter.com/UniWestArc/status/1178592065262780417

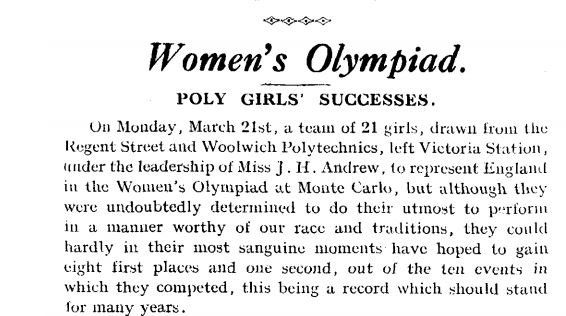

A journal clipping about the “poli girls” leaving UK for their trip to Monte Carlo

Source: https://twitter.com/UniWestArc/status/1178592065262780417

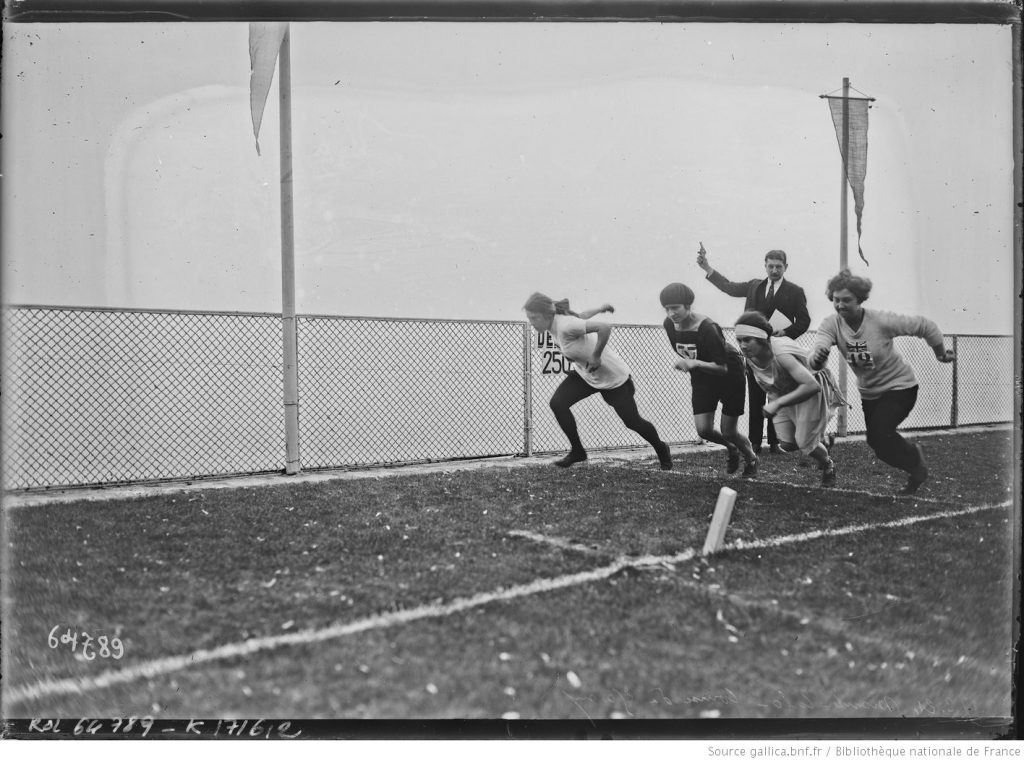

The start of a race: Note the DEPART ‘start’ sign

Source: https://twitter.com/UoGArchives/status/1066271457175515136

A group photo of the ‘poli girls’

Source: https://twitter.com/UoGArchives/status/1066271457175515136

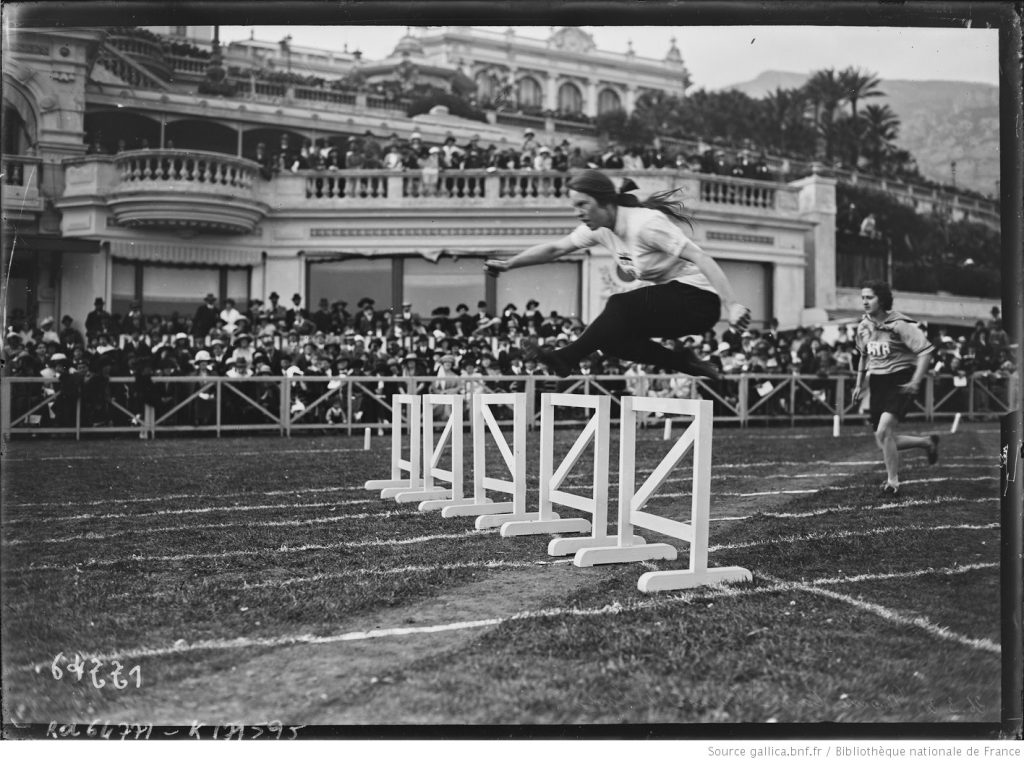

The English sprinter Mary Lines, winner of 60m, 250m and long jump, was the star of the 1921 Oympiad, as seen by the several photos depicting her.

Mary Lines, born in 1893, studied at the Regent Street Polytechnic and worked as a waitress

She retired from competition in 1924, and married Mr. Smith: as usual in 1920s Europe, the marriage was also the end of the sporting career

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1921_Women%27s_Olympiad .

Mary Lines winning the long jump

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53062815f

Mary Lines winning the 60m

Note that almost participants in the final were British women, except for the one on the right, probably a French women

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53062866z

Some of the wonderful photos from the Gallica database show us that the athletics event took place in the garden of the famous Casinò …

Mary Lines during the 65m hurdles

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53062850v

Pictures taken from another prospective show that on the other part of the gardens there was … a banister, and then the sea!

Hilda Hatt (GB) during the high jump

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53062870p

The start of the 250m

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53062866z

The 250m, won by Mary Lines

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530628803

Despite these frustrating results, the trip to Monaco was important because only after that the first-ever Italian national athletics meeting was held in Busto Arsizio in September 1921. While the women were competing, the (male) leaders of their sports clubs and the La Gazzetta dello Sport journalist Luigi Ferrario organized a meeting to discuss the development of women’s sports in Italy.

In the following months, the PE teacher Anita Podestà Vivarelli founded another centre for the development of women’s sport in her club, the Forza e Coraggio, located in Milan: for this reason, the first-ever National women’s Athletics Federation, the Federazione Italiana di Atletica Femminile (FIAF), was founded in Milan on 6 May 1923, and not in Busto Arsizio. 15 sports clubs were among the founders, and 7 of them (Unione Sportiva Milanese, Sport Club Italia, Forza e Coraggio, Costanza, Sport Club Pirelli, Ricreatori Laici, Libertà e Umanità) were from Milan! On the board of FIAF there were not only Luigi Bosisio (USM President) and Luigi Ferrario, but also a woman, the Pro Patria trainer Matilde Candiani. During the same time, the first official Italian Women’s Athletics National Championship was held in the Forza e Coraggio sports centre, and the Pro Patria athlete Maria Piantanida was the woman of the day: taking the the 80m, 83m hurdles, long jump, two-hands javelin throw and 4x75m relay gold medals!

The 18-years old Maria Piantanida during the 1923 National Championship, at the Forza e Coraggio sports centre: she is wearing the Pro Patria white-and-blue striped shirt

Lina Banzi, here depicted with a discus, was the other leading Pro Patria athlete

Together with Maria Piantanida, she joined the 1921 Olympiad

Lina and Maria composed the first-ever couple of friends and foes in the history of Italian women’s athletics, before the more famous Ondina Valla – Claudia Testoni …

Source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lina_Banzi.jpg?uselang=it

After retiring, Lina Banzi devoted her life teaching PE, as can seen from this photo taken on or before 1938, probably in Arena Civica (Milan)

Source: «Donne negli stadi», Sport Illustrato, December 1938, p. 10.

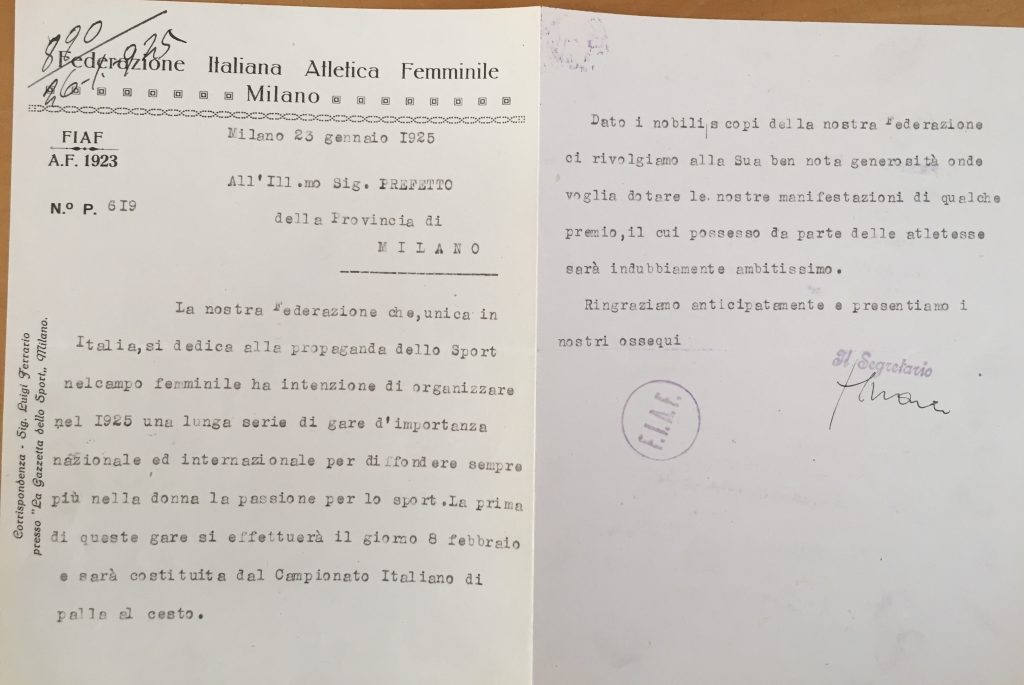

The first source from the Archivio di Stato was written on January 1925 by the FIAF Secretary (Luigi Ferrario himself) to the Prefetto. The journalist first remembers that “our federation is the only one who tries to spread out women’s sport in the country”, in order to develop among women the “love for sports” (please note the absence of any reference to an international result). Then Ferrario announces that in February the 2nd edition of the national women’s basketball national championship to be held in Milan – in fact, at that time basketball wasn’t an independent sport, but it was always practiced by Italian women with gymnastics and/or athletics. Finally, Ferrario asks the Prefetto to donate some prizes, writing that athletes would work hard to gain them. As we’ve already seen in Part 2 (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/historical-treasures-from-milan-archivio-di-stato-part-2/ ), a lot of people wrote to the Prefetto or to other dignitaries requesting prizes. In this particular case, Ferrario is quite ambiguous: on one hand, he describes the female athletes as ‘little girls’ eagerly staring at the medals; on the other hand, we should remember that in 1920s Italy, talking about female competitiveness was a very ‘open-minded’ issue, because females were taught not to be competitive – which was and still is a keystone of the patriarchy.

The first letter by Ferrario to the Prefetto

Note that the address (written in vertical on the left) is La Gazzetta dello Sport headquarters, where Ferrario worked

Source: b. 1114.

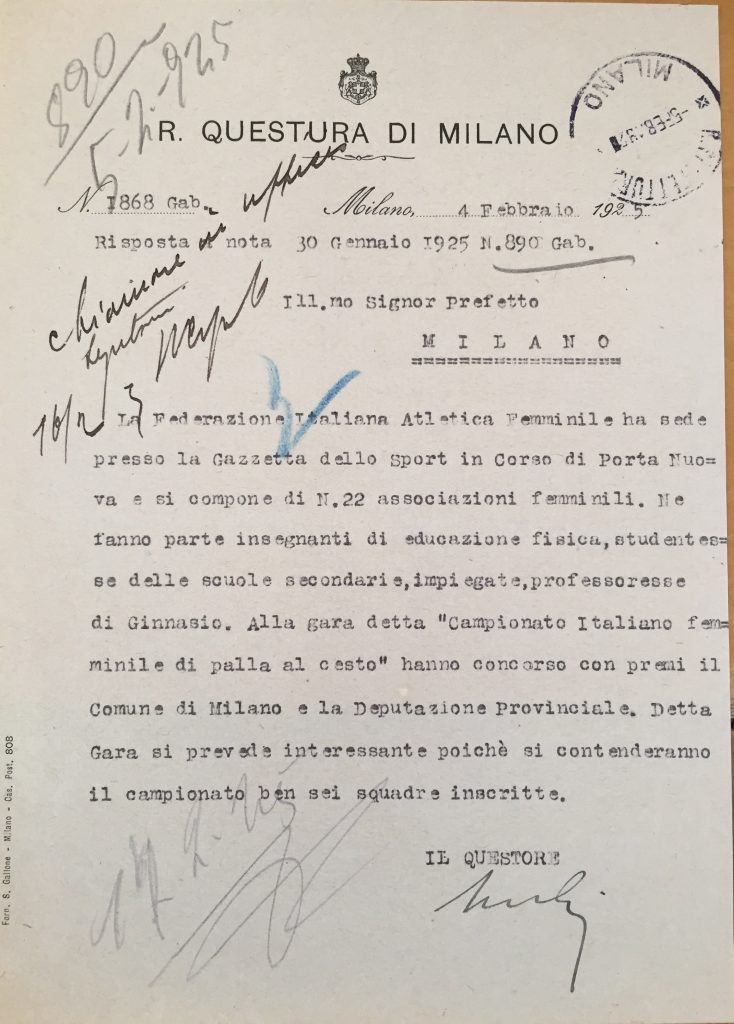

As usual, before answering, the Prefetto ordered one of his assistants to undertake some enquiries: in the second document, we can read what the Questore wrote to the Prefetto on 30 January 1925. The FIAF located in Corso di Porta Nuova (La Gazzetta dello Sport headquarters) is described as the federation of 22 women’s sports clubs: their members are female PE teachers, high schools students and teachers, office workers (quite the same social milieu of the 1933 calciatrici …). The Questore writes that 6 teams will compete in the basketball tournament, which is described as an “interesting event”; the Municipality of Milan, and the Provincia of Milan had already given prizes: the Prefetto wouldn’t be the only dignitary supporting the event.

The Questore’s letter to the Prefetto

Source: b. 1114.

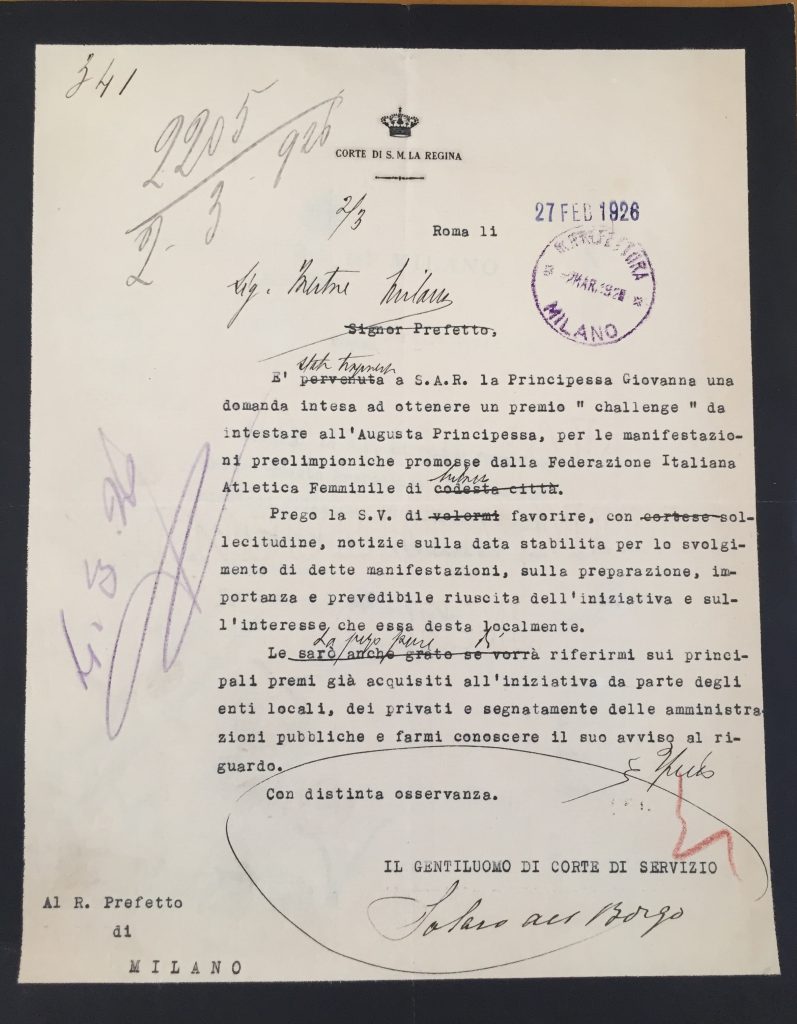

One year later, the Prefettura’s attitude towards FIAF got worse, maybe because, despite the generous help, the federation struggled with reaching its goals. In a letter written in Rome on 27 February 1926, a groom of the Bedchamber of Princess Giovanna of Savoy (King Vittorio Emanuele III’s daughter) asks the Prefetto about FIAF, which had requested that a prize but named after the Princess during an athletics event to be held in Milan. The groom would like to be informed about the FIAF, the event and the good name of FIAF among Milanese citizens.

The groom’s letter to the Prefetto; on the letterhead, ‘Court of Her Highness the Queen’

Source: b. 1114.

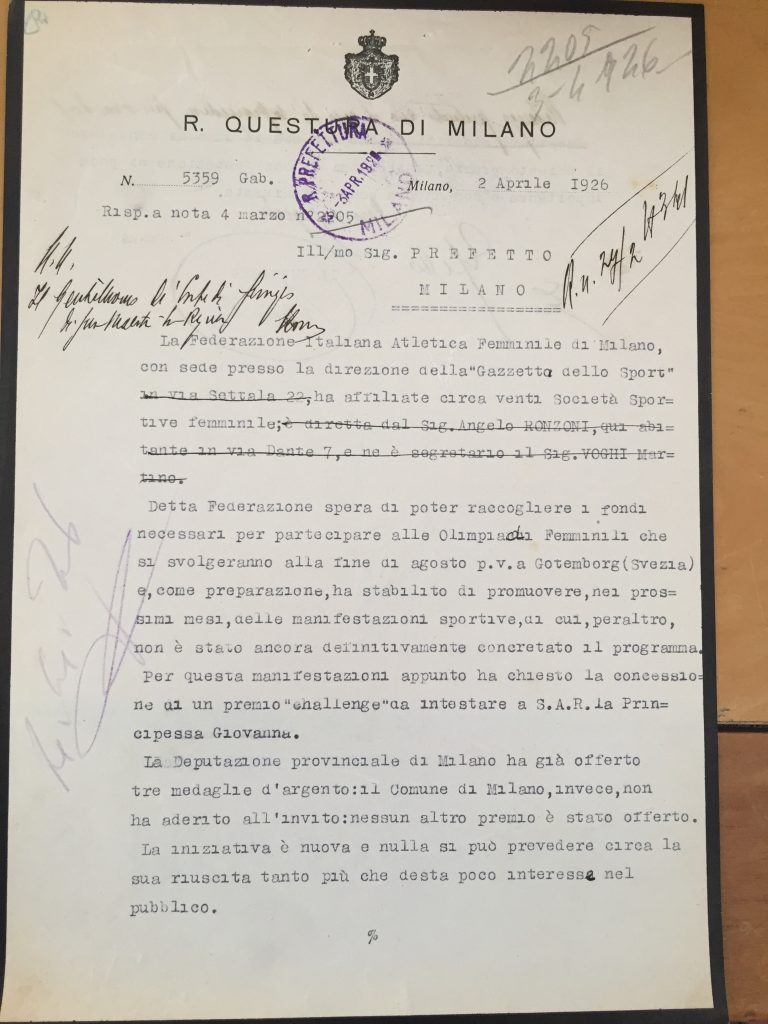

On 2 April 1926 the Questore wrote to the Prefetto, with the requested information, so the latter would be able to reply to the groom. The Federation, composed of 20 women’s sports clubs, was eager to raise funds to build up an Italian National Team to send to Gothenburg, where the 2nd edition of Women’s World Games was to be held in late August. For these reasons, FIAF decided to organize a number of athletics meetings, but there’s still a definitive program. Only the Milan Provincia gave a prize: the Municipality of Milan refused to give one and so no one else did either. The conclusion is clear

“this sporting event is new and it was impossible to make any predictions about it’s success; the public opinion is very little interested in it. So I think the best would be not to grant up to now a prize: it is an event of very little interest, and not yet organized”.

The Questore’s letter to the Prefetto. The handwritten signs tell us that the Prefetto’s answers to the groom was based upon this letter, with the necessary changes

Source: b. 1114.

In 1930 Luigi Ferrario wrote an article for the La Gazzetta dello Sport readers about the upcoming 3rd edition of the Women’s World Games, to be held in Prague: it was going to be the debut for the Italian team, because ‘in 1922 the women’s sport was taking its first steps in our country, and in 1922 we didn’t went to the Gothenburg Games because the funds failed on the very last moment’.

The Sweden National Team during the opening ceremony of the Gothenburg Games

Source: https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internationella_kvinnospelen_1926

Edith Trickey (GB) wins the 1000m, Inga Gentzel (Sweden) takes the silver medal

Source: https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internationella_kvinnospelen_1926

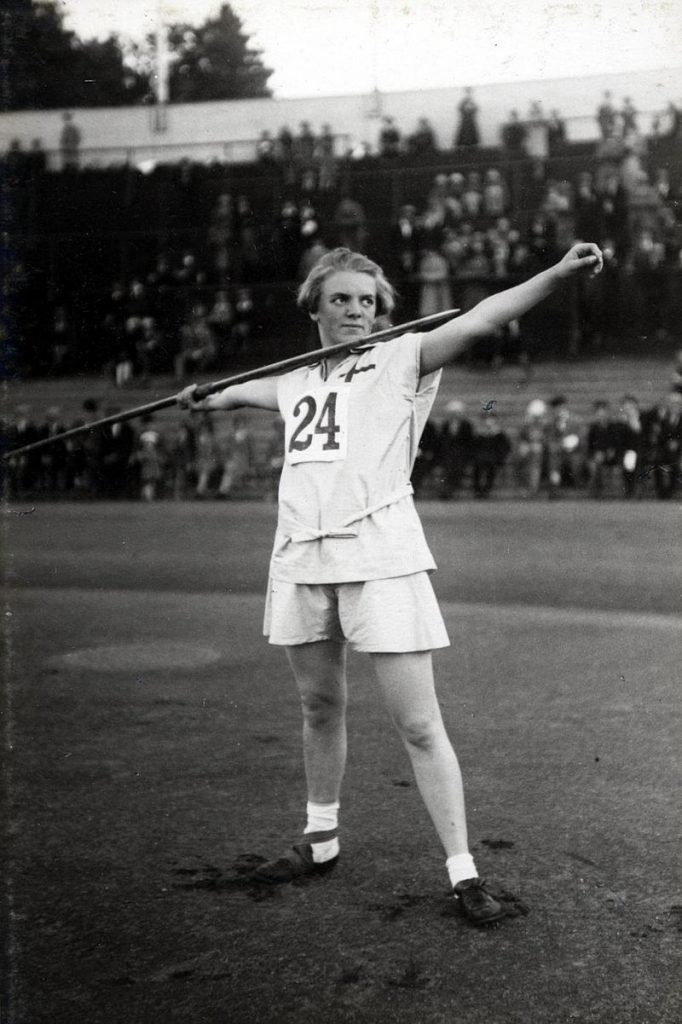

Anna-Lisa Adelsköld (Sweden), winner of the javelin throw

Source: https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internationella_kvinnospelen_1926

In 1926 Emilio Brambilla was elected as new FIAF President, while Luigi Ferrario joined the IAAF Committee for the development of women’s athletics. In 1927 the FIAF was able to organize the National team, which on 11 September 1927 debuted in its first-ever international meeting, held of course at the Forza e Coraggio sports center. The Italian women were of course defeated by their French opponents (27 to 54), yet the point was that, finally, Italy had its own National team: a fact that was very important, in the country which had meanwhile fallen under the fascist regime. The following year, the 1928 Summer Olympics Games were held in Amsterdam, and the new Mussolini’s Italy, which finally decided to send some female athletes to the Olympics for the first time, could bear no international debacle.

The opening ceremony of Italy-France athletics meeting

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1378278636114079746

The fact was that the Italian girls who were sent to the Netherlands had disappointing results in the athletics events: they were all eliminated in the preliminary heats, and Pierina Borsani was 13th in the discus throw!

A video about women’s athletics events at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympic Games

Source: https://youtu.be/gCwb_IEMCRg

The 16-years old Elizabeth Robinson (USA), winner of 100m gold medal.

Source: https://youtu.be/zGcC2kn4qgU

Ethel Catherwood (Canada), gold medal in high jump

Source: http://canadasports150.ca/en/canadian-women-in-international-sport/matchless-six/14

Halina Konopacka, discus gold medallist and the first-ever Polish Olympic gold medal winner

In September 1939 Halina helped her husband Ignacy Matuszewski, (former Minister of the Treasury) evacuate the gold reserves of the Polish National Bank to France to help finance the Polish government-in-exile

After France surrendered to Germany in June 1940, the couple immigrated to the United States, where she died in 1989

Source: https://twitter.com/Jan34733995/status/1289166830209249283

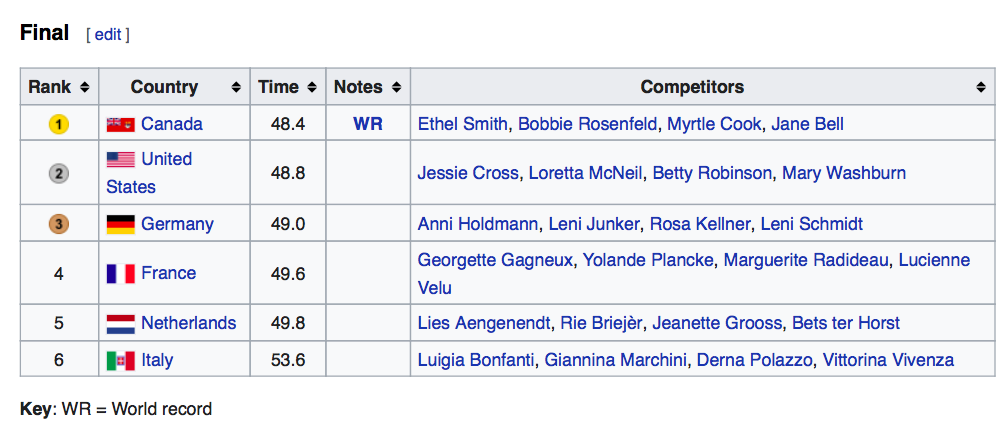

The best result was 6th place in the 4x100m relay, which was however a humiliating one. Luigia Bonfanti, Giannina Marchini, Derna Polazzo and Vittorina Vivenza tried to do their best, but while the Canadians established a new world record (48” 4/10), the Italians were last almost 4 seconds behind the team in 5th! Thanks to the left-hand side of this video https://twitter.com/Olympics/status/1032689678304997379 , we can see the light-blue shirt of the Italians just during the first change …

The Canada winning relay team

From left: Jane Bell, Myrtle Cook, Ethel Smith and Bobbie Rosenfeld

Source: http://canadasports150.ca/en/canadian-women-in-international-sport/matchless-six/14

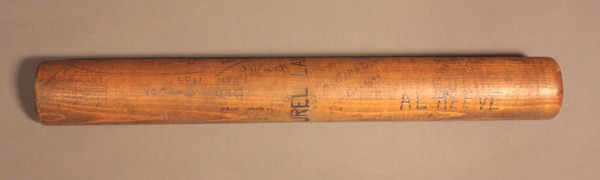

A relay baton used by the Canadians – probably not the one used in Amsterdam, but signed by Myrtle Cook

Source: http://canadasports150.ca/en/canadian-women-in-international-sport/matchless-six/14

The results of women’s 4 x 100m relay final

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athletics_at_the_1928_Summer_Olympics_–_Women%27s_4_×_100_metres_relay

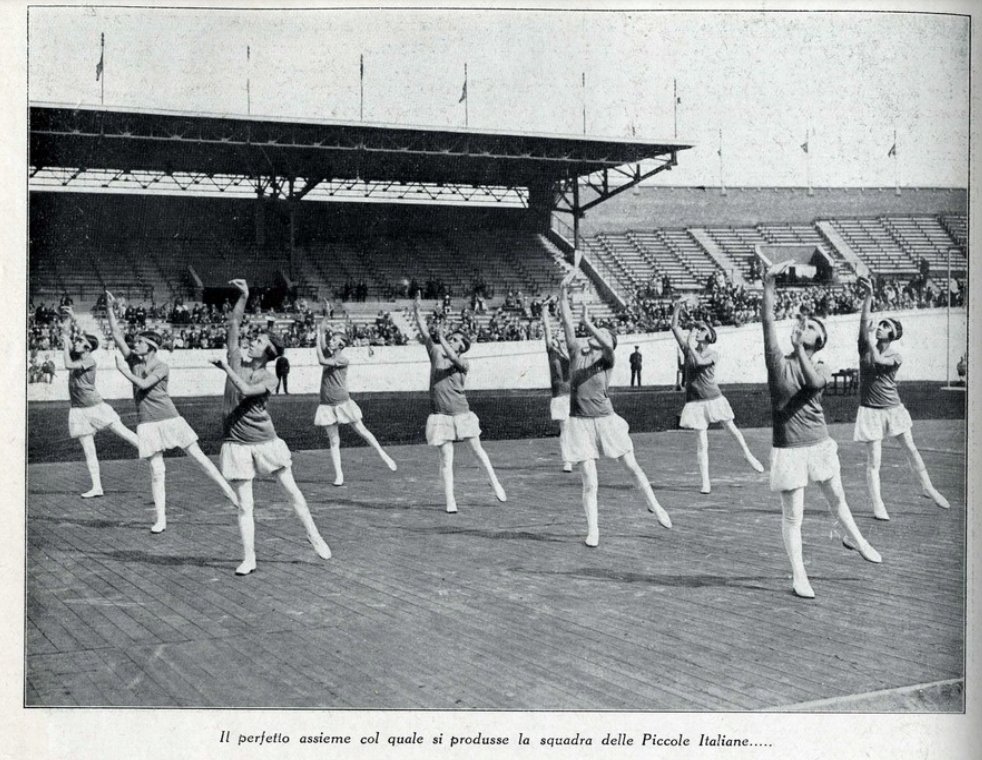

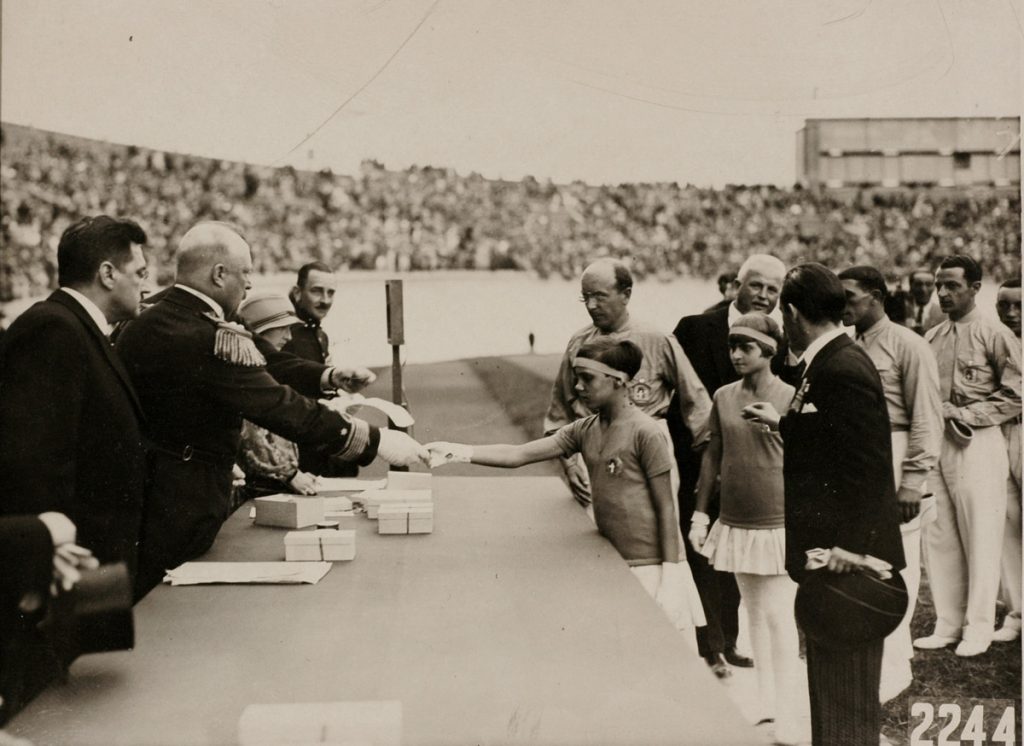

The best female results for Italy were in gymnastics: the team composed of very young gymnasts from Pavia won a silver medal!

The Pavia gymmasts with the Italian flag

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, August 1928, p. 53

The Pavia gymnasts in action

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, August 1928, p. 60

The Pavia gymnasts were very young, as you can see in this photo: most just 13 or 14 years-old

One of them, Carla Marangoni, had a little talk with Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, telling her that she was fond of football!

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1249702055918403594

After the Olympic Games, there was a public debate about the utility of FIAF, which was seen as responsible for the Italian fiasco. In September 1928 Luigi Ferrario wrote an article published by La Gazzetta dello Sport: in his opinion, the FIAF should remain an independent federation; its dismal results were caused by the lack of funding. In order to avoid the possible incorporation of FIAF into FIDAL (the male athletics federation), Ferrario invoked the ghost of promiscuity, which was an important issue for the Italian public opinion.

The 1928 National Women’s Athletics Championships, held in Bologna in October 1928, were the last ones organized by the FIAF, which was dissolved by the regime in the very last days of that year. On 30 December 1928, the Secretary of National Fascist Party and President of the CONI (Italian Olympics Committee) Augusto Turati decreed that ‘The FIAF shall no more be an independent federation: it will be integrated onto the FIDAL’.

In 1929 the new era of women’s athletics ruled by the FIDAL began, and Marina Zanetti (here with javelin thrower Elvira Faccin) would be the a very important manager of the national movement, as we already seen in https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/gender-and-sport/the-relay-runners-who-joined-the-resistance1930s-1940s-italian-athletes-lydia-bongiovanni-and-elda-francopart-1/

Source: Lo Sport Fascista, January 1930, p. 39

To read Part 4 – click HERE

Article © of Marco Giani

For more details about the Sports History funds at the Milan Archivio di Stato, and the transcription of all sources quoted in this article, see:

https://www.academia.edu/43667097/Fonti_per_la_storia_dello_sport_nellArchivio_di_Stato_di_Milano

For more images about Italian 1920s’/1940s’ women’s athletics, see:

https://sorelleboccalini.wordpress.com/le-fonti_sportive-del-ventennio/