With the digitalisation of archival materials, especially materials relating to genealogy such census material and the birth, marriage, and death records (BMD), sports history has seen an increase in the production of research relating to the individual, as well as the utilisation of new biographical methods. Whilst prosopography, which has effectively been utilised by the likes of Oldfield, Taylor, and myself, has been helpful in developing the external biographical elements (birthplace, occupation, club memberships, etc.) of the average members of the population, it lacks the ability to explore a subject’s inner characteristics, such as their motivations, opinions and ideas. This is where an individual biographical approach still excels. Whilst prospography overcomes issues of using biographical data that is inherently individualistic and too unique to make generalisations with, that is not to say that an individual biography cannot be used to the same, although limited effect. Through descriptions of the individual and their interaction with the environment and other historical actors, it is possible to explore complex historical developments in the context of a case study via the use of themes and trends. Presented here are the abridged biographies of Thomas Abraham, James Atkinson, and Francis Webb, all London and North Western Railway Company (LNWR) employees based in Crewe during the nineteenth century, and an examination of the shared aspects between these three men.

Thomas Maxfield Abraham (1851-1928)

Born in 1851, Abraham started life living with his chemist father William, and his wife Rebecca, before being left in the care of his uncle, Thomas Beech, a well-known farmer and landowner, when the rest of his family moved to Staffordshire shortly after Thomas was born. In 1866, a 14-year-old Abraham had joined the LNWR as an apprentice clerk in the accountant’s office, subsequently working for the railway company all his working life spending the majority of his time in the accountant’s office. Shortly after joining the railway company, Abraham, and several other interested individuals, formed the Crewe Alexandra Cricket Club, with the idea for the club supposedly coming from Abraham’s childhood, where he spent the majority of his time playing cricket in the fruit orchards of his uncle’s farm. When the Alexandra club decided to form a football section at a meeting held at the Castle Hotel in August 1877, Abraham was amongst those appointed to oversee the arrangements and upon the formation of the Cheshire Football Association in 1878, he was appointed secretary of the organisation. However, it was his contribution to amateur athletics that made him such a well-known figure in the sporting community. The athletic festival that the Alexandra club hosted annually at the Alexandra Recreation Ground and Earle Street Recreation Ground expanded over the course of the century to become one of the ‘premier athletic gatherings in the Kingdom’ and Abraham was given much of the credit for its development. Abraham’s talents in organising and management certainly made him influential in the development of the Alexandra club and he was credited with keeping the club financially healthy. There was general agreement as well that the success of the annual athletic festival, which boasted ‘a renowned programme of excellence’ and was ‘admirably conducted’, as one of the principal athletic meetings in not only the North, but throughout England, could be attributed to his efforts.

Thomas Maxfield Abraham

In 1879, the Northern Counties Athletic Association (NCAA) was formed due to the dissatisfaction of northern athletic enthusiasts, and whilst it was George Duxfield, a famed northern amateur athlete, who initiated the process in which the NCAA was created, Abraham was one of the first to publicly express support for Duxfield’s idea for the north to have its own championships. Furthermore, Abraham believed that due to the poor state that the sport was in during the 1870s, an association of sufficient power was necessary to deal with competitors of questionable character. A year later, when the NCAA received an invitation from members of the Oxford University Athletics Club to form a nationally focused athletic association, Abraham, alongside four other northern men, was given full discretionary powers to act on the behalf of the NCAA at the meeting held at the Randolph Hotel, Oxford, on April 24, 1880. Abraham served on the executive committee of both the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) and the NCAA uninterruptedly until age reduced his involvement, and he was the honorary treasurer and twice president of the NCAA, as well as serving as a vice-president of the AAA for nearly twenty years. During that time, Abraham made a significant contribution to amateur athletics, and was determined to protect northern interests on the national stage, a determination which almost caused the AAA to split apart on two occasions. On June 1, 1928, Abraham died at his home of pneumonia and senility, aged 79, ending sixty years of ‘dedicated service to organised amateur sport’.

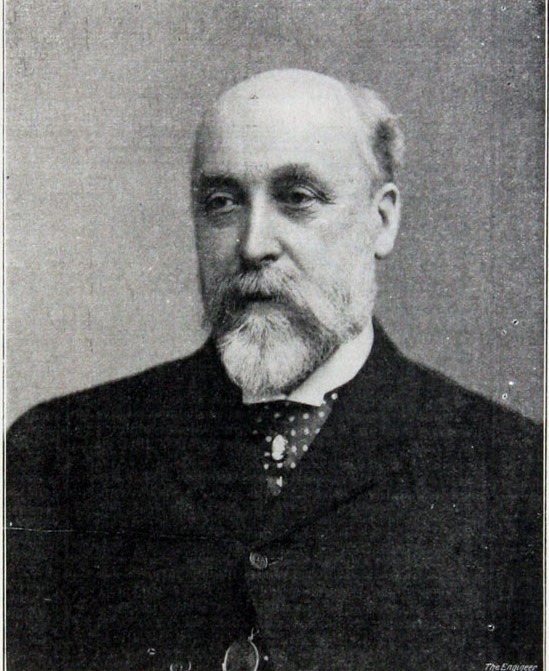

Francis William Webb (1836-1906)

Born on May 21, 1836, at the Tixall Rectory, Staffordshire, Francis William Webb was similar to Abraham, in regard to being born into what is considered to be middle-class family. Showing a keen interest in mechanical pursuits at an early age and on August 13, 1851, he joined the LNWR and became a pupil of Francis Trevithick, the son of the famed Richard Trevithick, the company’s first Locomotive Superintendent. He served as an apprentice and upon completion of his apprenticeship in 1856, Webb joined the drawing office. In February 1859, Webb was promoted to the position of Chief Draughtsman and two and a half years later, in September 1861, Webb was promoted again when he was appointed as Crewe Work’s General Manager. Whilst Webb left the LNWR in 1866 to take up a partnership and manager’s position at the Bolton Iron and Steel Company, he returned to the company in 1871 as the Chief Mechanical Engineer and Locomotive Superintendent, making him responsible for 13,000 men, Crewe’s locomotive facilities, and the design and execution of all mechanical engineering processes for the LNWR rail network.

Whilst the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s legacy tended to be their locomotive design work, this only formed as a small segment of Webb’s overall contribution to English locomotive history, and he is perhaps most well-known for the handling of his primary responsibility within the company, the running of the vast network of the locomotive department. As part of his responsibility, Webb was the LNWR’s primary representative in Crewe, and, therefore, it was expected of Webb (and his successors) to be active within the community. A keen cricketer, Webb often supported the Crewe Alexandra Club in their endeavours, not least in petitioning the company’s directors to donate company land on Earle Street so that the club were not left displaced when the LNWR needed the land on Nantwich Road to expand the permanent way around the train station. When the new ground was officially opened on May 21, 1898, Webb was invited to provide the keynote speech and was given the honour of receiving the first ball of the match. The assistance provided by Webb, however, was not provided out of charity. Webb believed that ‘a healthy body conduced to a healthy mind’, the typical view of most members of the middle class, as reflected in their newfound enthusiasm for public health, and, by providing a place for his employees to exercise and relax, Webb ensured that they would come to work energised and productive.

Francis William Webb

Webb also held strong views on how sport should be played. Like many of his other middle-class contemporaries, who supported the exclusion of professional competitors and gambling, Webb believed that sport should be played without thought of monetary gain. Shortly after the schism between the Crewe Alexandra Club and its football department, Webb and the LNWR released a statement stating that the company would ‘refuse to find employment in the Crewe Works for any professional football player’. Whilst this was not popular with the town’s residents, the decision was imposed to try to force the club to disband or to change its decision on their professional status. Webb was also, for a time, president of the Crewe Cricket Club, Crewe’s other major cricket club, and was one of the vice-presidents of the Memorial Cottage Hospital ‘Cup Competition’, an annual football competition organised locally between what appears to be Crewe Works-based teams in order to raise money for the local hospital. Away from sport, Webb also supported various ‘middle-class’ activities, and was the president of the Crewe Mechanic’s Institution Chess and Draughts Club, the Philharmonic Society, in which the Duke of Westminster was the society’s main patron, the Scientific Society, Shorthand Writers’ Association, and the Horticultural Society. Webb was also the vice-president of the Chrysanthemum Society.

During the 1880s, Webb became progressively more involved with the politics of the town. In 1880, Atkinson, who at this point was the leader of Crewe’s Conservative Party, approached Webb seeking permission to form a committee of Works foremen to approach prominent company officials in the town to get them to stand as ‘Independents’. This started a decade-long political struggle, known as the ‘Intimidation Affair’, which captivated political commentators, until the Independent Party ignominiously collapsed in 1891. As the company intensified their presence within the town’s political landscape, Webb became directly involved and he was elected as the town’s mayor in 1886 and 1887. From the letters that were penned by Webb a decade earlier regarding his employee’s obligations to the company, as well as noting the tactics employed by the foreman committee, which included standing at the entrance of the polling booth and reminding voters who provided their ‘bread and cheese’, it is unsurprising that Webb won election due to fear of reprisal and intimidation. Ultimately, Webb’s influence on all aspects of local life, together with his substantial philanthropic contributions, earned Webb the nickname ‘the king of Crewe’. On June 4, 1906, Webb died in Bournemouth, retiring from the LNWR three years previously.

Dr James Atkinson (1837-1917) Born in Hazel Grove, Stockport, in 1837, James Atkinson was unlike his other LNWR counterparts being the son of a local Blacksmith, signifying that Atkinson came from an artisanal working-class background. After qualifying from the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1863, Atkinson came to Crewe as an assistant to Dr Edwin Edwards, the head surgeon of the LNWR. Upon the death of Edwards in 1865, Atkinson inherited the position as the company’s head surgeon at Crewe. Like many contemporary doctors, Atkinson had an extensive private practice, which dealt with both medical and surgical conditions. As the company’s surgeon, Atkinson was outside of the LNWR’s managerial structure, and therefore, had less pressure to engage in public life, unlike Webb, his successors, and other railway. However, Atkinson was very much active within the social spheres of the town during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in the context of sport. He attended the first Crewe Alexandra Athletic Festival where his wife presented prizes to the winners of the various events. Atkinson served as the club’s president from at least 1896 until 1909. He was also involved with the Crewe Memorial Cottage Hospital ‘Cup Competition’. Atkinson was also one of the directors and chairman of the Crewe Cattle Market and Abattoirs Company, as well as the president of the Crewe Orchestral Society, and he was involved with the Crewe Engineer Corp, regularly attending camp with the battalion.

Whilst Webb commanded significant influence locally and regionally, he was not alone in pursuing the company’s objectives at the local and county political levels. Whilst a medical professional by trade, it was Atkinson’s political activities that make him a noteworthy individual in the town’s history. Despite having no political experience, Atkinson was elected as the town’s first mayor in 1877 suggesting that, at this point in his life, he was quite popular in local circles. A close friend of Webb, it was Atkinson that persuaded Webb to establish a committee of Crewe Works foremen in order to get prominent LNWR officials elected to the council during the 1880s, and upon the formation of the Cheshire County Council, Atkinson, alongside Webb, was one of the town’s three representatives. Atkinson was also vice-president of the Conservative Association in Crewe before becoming their leader, as well as being the leader of their Parliamentary division. Shortly after the county was divided into single-member constituencies, Atkinson was invited to become the Unionist candidate for parliament but declined and instead, gave his support to another candidate instead. Atkinson became one of the primary figureheads for the LNWR’s involvement in local politics, despite there being a wider selection of more experienced railway officials available, such as John Rigg, George Wadsworth, and the Worsdell brothers. Atkinson died on March 9, 1917.

Dr James Atkinson

The Sporting Railwaymen of Crewe: A Discussion

Sport and Middle-Class Amateur Values

Whilst the three men presented here differ significantly in terms of job role within the LNWR, as well as their position within local society, there are many shared aspects of their lives, despite their difference in occupation, income, and status, such as their common belief in amateur values. the values of sport, participation, and the importance of taking part, all became subject of debate during the nineteenth century, with sport reflecting wider social tensions and conflicts within Victorian society. As sport became more competitive, with bigger stakes and rewards for success, as well as the gambling that was associated with professional sporting practices such as pedestrianism, some middle-class sportsmen began to denounce the notion of serious competition. This amateur philosophy, which advocated fair play, as well as playing for enjoyment rather than for financial incentives, significantly influenced the way that English sport was organised, especially in the final quarter of the nineteenth century. As a result, sport historians have often credited public school alumni for being the organisers of, and champions for, amateur sport during the Victorian period. However, the northern middle class were significant in the development of athletics during the last twenty years of the nineteenth century, and research suggests that the north dominated the sport, especially in the context of administration. These three LNWR men shared an enthusiasm for amateur sport, despite not going to any of the prominent public schools in England, as evidenced by Abraham’s involvement with the NCAA and AAA, Webb’s restrictions of professional sportsmen in the workplace, and Atkinson’s chairmanship of the amateur athletic club.

Historians previously have argued that the north of England had ‘warped sporting instincts’ in the context of the amateur and professional debate, and that ‘the ethos of the southern sporting establishment…remained, at heart, at odds with the grassroots play of the broad mass of the industrial population’. Baker describes a ‘sub-hegemony’ within the north exercised by the northern industrial and merchant middle classes, which boasted entrepreneurial ideals and placed an emphasis on competitive success. The biographies of Abraham, Webb and Atkinson, however, seem to contradict these conclusions and suggest that, whilst a professional culture did exist in northern sport, the nineteenth-century amateur movement was very much alive in the North, and was supported at all levels by the northern middle classes.

Political Engagement within Crewe

The social control of Crewe’s population by the LNWR was exerted through multiple spheres of community life. In the context of sport and leisure, the company had an extensive network of managers and prominent employees that were part of the town’s various clubs, associations, and societies, who, in turn, influenced the way that these organisations developed and grew. There was also an element of using economic power to influence the way that local sport and leisure developed, as evident by the company’s decision to exclude professional football players who were employed within the company when the Crewe Alexandra Football Club turned professional in 1891. By involving themselves in every aspect of their worker’s lives, as well as in that of their families and neighbours, the company’s management could instil their own middle-class values and ideas onto the population. Through these strategically located figures, the LNWR became part of the town’s political establishment. As the town became more significant politically and evolved into a municipal borough through incorporation in 1877, the railway company saw the benefit of having control of the town’s newly formed elected council. At the forefront of this initiative was Webb and Atkinson. The railway company used an extensive network of their prominent employees and those involved with the company’s management ranging from its foremen, up to its mechanical engineers and superintendents. As the head of this locally centred network and as two of the company’s most prominent employees outside of London, Webb and Atkinson were in the best position to become county-based politicians and ensure that the LNWR’s interests were best represented at this level.

Paternalism and Railway Patronage

Patronage of industrial and commercial companies played an instrumental role in providing sport and leisure for the working class. Whilst moral and religious beliefs persuaded some employers to provide sporting spaces for their workers, the pursuit of profit drove other companies in this respect, as well as the desire to develop a broader company culture. The LNWR were not alone in this strategy of supporting sport and leisure within the local community. The patronage of sport and leisure was an important aspect of company life for Alfred Herbert Ltd., a company founded in 1888 that produced machine tools, Sir Alfred and his wife appearing frequently at sport festivals and team matches in order ‘to be seen as a benevolent paternalist in action’ and to ‘play the role of [the] paternalist’, by presenting prizes and medals at events. Webb, alongside Atkinson and his wife, displayed similar behaviour by playing a prominent place in Crewe’s local events, many of which were organised by Abraham. Webb and Atkinson were frequently the guest of honour at various events within the area owing to their position as senior railway representatives, and as former mayors of Crewe. In companies like the LNWR, the work for the majority of its employees was quite physical, so it was critical for their employees to be healthy in both body and mind, whilst also adopting middle-class notions regarding fair play and sportsmanship.

Whilst Webb and Atkinson obviously had a significant impact on the company’s paternalistic policy, having a substantial input in deciding what that policy was and how it should be delivered, Abraham, a clerk much lower down the company’s hierarchy, had less influence in this respect. However, he still had an indirect impact on the company’s social control agenda, using sport as a means of controlling its workers and the town. By forming the Crewe Alexandra Cricket Club in 1866, Abraham created a space for the LNWR to control. As his biography shows, Abraham also contributed significantly to the development of the nineteenth-century amateur ethos via his connection with the NCAA and the AAA, by ensuring that northern athletics, and ultimately, national athletics, took a firm stance on limiting professional practices and gambling in the sport. This means Abraham supported Webb and Atkinson in the promotion of values that they, and the company, endorsed, as emphasised by Atkinson’s presidency of the athletics club during the 1890s and 1900s, and Webb’s open hostility to professional sportsmen.

Whilst each individual’s life story is unique and arguably, incomparable to someone else, by highlighting and exploring key themes and ideas, such as attitudes to amateurism, paternalistic behaviour and political actions, it is possible to connect unique biographies in a way that allows historians to use these individuals to study broader historical developments. By presenting the biographies of Abraham, Webb and Atkinson and then comparing key themes, it shows both the uniqueness of all three men’s life story and how they are all connected beyond a shared working and living space. All three individuals were keen supporters of amateurism and contradicts the established view that northern sporting culture evolved into one that placed a heavy emphasis on winning and commercial gain when compared to the south of England, which is considered to the centre of the amateur movement. Ultimately, the findings presented here, as well as the findings presented elsewhere by the likes of Porter and Harrison, demonstrate that the amateur-professional dichotomy in the context of the north-south divide is not as easily definable as previously suggested. By contrast, the political activities of Webb and Atkinson described here are less surprising and are more in line with the established literature regarding political activity in industry-dominated urban spaces. Both men were political ‘heavyweights’ in the local context, using their economic and social influence respectively to be elected to the town council during the 1870s and 1880s and supports the theory that the LNWR used a complicated network that comprised senior management and socially-prominent employees to infiltrate every aspect of local life.

Whilst these biographies offer an insight into the northern industrial middle class and their relationship to both sport and paternalism, they also offer the opportunity to reflect on the use of biography as a method historical inquiry. As noted by Adejunmobi, ‘history is biography and biography is history’, suggesting that history is in essence, a collection of an incalculable number of biographies all woven together to form what is regarded as human history. Whilst historians are increasingly advocating broad biographical studies, such as prosopography, that focus on a collection of individuals, a notion that obviously has merit in terms of presenting a more holistic view, in certain cases, such as the one presented here, it is only by studying individuals, such Webb and Abraham, that we can see the impact made by the individual on historical events.

Article © Liam Dyer

Is it possible for you to tell me where Dr Atkinson had his private surgery and do you have any information on his family as I think that I may related. Thank you