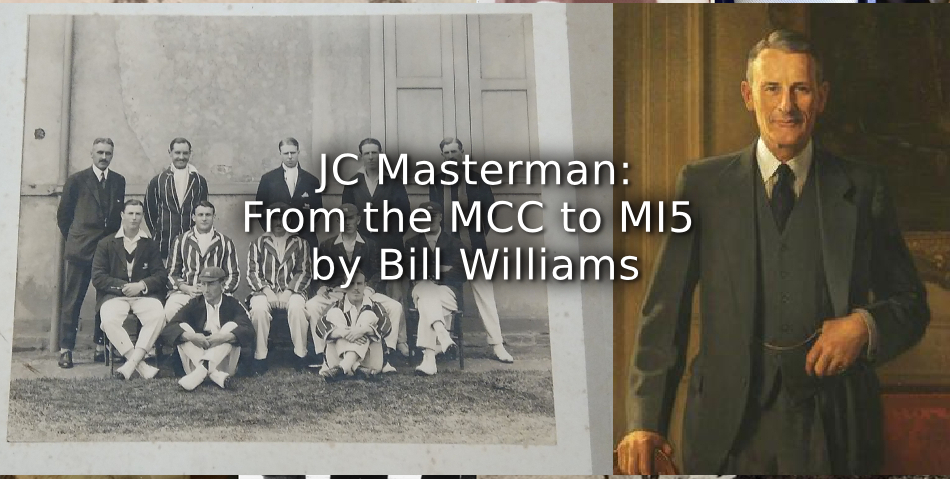

J.C. Masterman is not a name that is perhaps very widely known, despite the fact that in the early years of the twentieth century, he was extremely talented across six different sports; gaining four international ‘caps’ for England at hockey, representing England at tennis and playing at Wimbledon, a ‘scratch’ golfer, equally skilled at squash and a ‘blue’ at Oxford for athletics as a high jumper and a cricketer for the MCC.

JCM (left) sitting with his mother and brother Christopher circa 1900

However most importantly and as the 80th anniversary of ‘D Day’ approaches, he should be remembered as the man responsible for the deployment of ‘double agents’ for MI5, during World War Two, which resulted in the ‘Ultimate Deception’ on June 6th 1944.

John Cecil Masterman (JCM) was born in 1891 into a naval family and was educated at The Royal Naval Colleges of Osbourne on The Isle of Wight and Dartmouth, however to the dismay of his parents, he chose to read Modern History at Worcester College, Oxford and turned his back on a career in The Navy.

As a boy whilst staying with his uncle in Nottingham he briefly met the hero of the 1902 Oval Test Match, Gilbert Jessop (very much the ‘Ben Stokes’ of his day), who sent him a book called, ‘Giants of The Game’ with a card inside; he was to keep both all his life and credited Jessop as one of the main reasons why he loved Cricket so much and noted: ’Small wonder that he became the first of all our Cricket heroes.’

Gilbert Laird Jessop

At Oxford JCM involved himself fully in the sporting life of the college, playing Tennis, Cricket and Athletics where, in his third year he won the high-jump competition against Cambridge with a jump of 5’ 8 inches (1m 72 cm) and The Morning Post saw reason to comment on his, ‘Springy foot and straightforward unsophisticated jumps’.

In 1914 at the outbreak of war, he unfortunately found himself at The University of Freiburg in Germany on an exchange, where he was expected to learn ‘something of German methods and German university teaching’, but instead was interned in a camp called ‘Ruhleben’ where he was to spend the whole of the Great War.

In his autobiography, ‘On The Chariot Wheel’ (published in 1975) JCM reminisced about his time there: ‘Two distinct pictures of the camp are retained in my memory; one is of a prison camp and covers three or four months and the other is of a civilised and active society, fully and purposefully engaged, which lasted for three and a half years.’ His time at the camp to his extreme embarrassment in later life had actually been in many ways, a very positive experience.

When the day came in November 1918, trains arrived to take him and the other 3,000 interns home to England via Hull and Catterick Barracks in Yorkshire; the war was over.

On his return he secured a position at Christchurch College Oxford, as a History tutor and embarked on a remarkable period of his life, which saw him emerge as a very accomplished international sportsman across a range of sports.

In 1919 he played his first match at Wimbledon and was beaten in the first round however, in the following year JCM was selected to play for England against Scotland and Ireland. He would reach the fourth round of the Men’s singles Tennis tournament at Wimbledon in 1923 and the Quarter- finals of the Men’s doubles with partner Charles Kingsley and would play his last matches there in 1930.

He was very philosophical about his tennis career and reflected on it in later life by saying

Had I succumbed to the temptation of trying to go further in the world of tennis I should, I feel sure, have regretted it. As things were I could enjoy Wimbledon in a carefree and amateur way and still achieve a reasonable measure of success.

- AE Stoddart

- Stanley Shoveller- ‘The Prince of Centre Forwards

In 1925 as a member of The Hampstead Hockey Club, he was selected to play Hockey for England. Founded in 1894 and derived from The Hampstead Cricket Club, it started to attract many fine sportsmen in the early twentieth century, which included the great A.E.Stoddart who had played Cricket and Rugby for England and had been a member of the first British Isles touring Rugby team in 1888 and Stanley Shoveller, known as ‘The Prince of Centre Forwards’ having scored 79 goals in 35 appearances for England. He had also picked up Gold medals at the 1908 and 1928 Olympics and a Military Cross in WW1.

Divisional trials were the next step and then divisional matches for the south’, recalled JCM in his autobiography. ‘It was interesting to observe how my pace and skill improved with each successive step and I never knew a side to play so well as did one of our South sides against the West, where we scored nine goals

JCM on the ball for England v Ireland in 1925 at Edgbaston . England won 4-2

JCM was also President of The Oxford County Hockey Association and played alongside the ‘prolific Hartley brothers’; Frank who was also an international footballer and county cricketer, Dick who also captained the county cricket team and Ernest who also played county cricket and captained England at hockey.

He recalled them with great affection in his autobiography in 1975:

My most vivid memory is of the three Hartley brothers who were Oxfordshire farmers and sportsmen of the best vintage; they formed the backbone of the county hockey and cricket teams and became the doyens of Oxfordshire sport.

The Oxfordshire County Hockey Team circa 1925

JCM sitting second from left in a team that included the three Hartley brothers

JCM was selected at inside forward in the first of four appearances for his country and claimed in his autobiography that,

The sport had done much to improve relations between the countries of Europe, who were rebuilding after the war.

As a member of ‘The Oxford University Occasionals’, JCM had embarked on a tour in 1923, which had taken him to Paris, Budapest, and Vienna where he had witnessed a match between Austria and Italy in front of a crowd that was estimated at over 40,000.

The England team

JCM is standing fourth from the left in a team captained by Oxfordshire’s Ernest Hartley

Despite these successes, it was Cricket that was always his greatest passion and between 1922 and 1925, he made 18 appearances for Oxfordshire,( alongside his England Hockey captain Ernest Hartley and brothers Frank and Dick) in the Minor Counties competition, as well as playing for several prestigious nomadic teams such as ‘I Zingari’,’ The Free Foresters’,( whom he toured to Canada with in 1923), HDG Leverson’s XI and ‘The Harlequins’, described by JCM as ‘The best of all.’

Oxfordshire CCC, 1922

JCM sitting second from the left

The club founded in 1852, was made up exclusively of current and former Oxford University ‘first –class ‘ cricketers and after the war he played consistently for the club and described why he felt it was such an honour to play for them:

To be a Harlequin was felt in the Oxford cricket world to be a high distinction and at times those who played would refuse an invitation to play for a first-class county.

However arguably, his finest hour as a cricketer would come at the ripe old age of 46, when he was selected to play again for The MCC on their tour to Canada, which would turn out to be his last (he had toured with them to Ireland in 1924).

The MCC squad for the tour of Canada in 1937

JCM is standing fourth from the left.

In 1975 JCM wrote

I was very much the veteran of the party and my bowling was not needed, but aided by a few good ‘not-out innings, I contrived to come second in the batting averages and as I also had a good many catches in the slips, I felt that I had pulled my weight. I was never a ‘first-class’ cricketer and never pretended to be, but I have had great good fortune to play for many different kinds of cricket of varying standards and in many places and to have enjoyed them all to the full.

His final first-class match came two years later, for ‘The Free Foresters’ against Oxford University, where the former England batsman Douglas Jardine (who had captained England in the infamous ‘Bodyline Series’ in 1932-33) scored 112 in a match that ended in a draw.

Alongside his work at Christchurch and his numerous sporting endeavours, JCM also found the time to write a novel entitled, ‘An Oxford Tragedy’; a ‘murder mystery’ published in 1933 followed almost twenty -five years later by the sequel, ‘The Case of The Four Friends’.

‘An Oxford Tragedy’ published in 1933

When war broke out for a second time, JCM was drafted into ‘The Intelligence Corp’ (mainly because he spoke fluent German), which was responsible for gathering, analysing and disseminating Military Intelligence and Counter Intelligence and after producing a report into the evacuation of Dunkirk, he was appointed as a ‘Civil Assistant’ to MI5 (Military Intelligence section 5).

In his autobiography he spoke warmly of the group he was tasked to work alongside:

In joining MI5 I became one of a team, a team of congenial people who worked together harmoniously and unselfishly and amongst whom rank counted for little and character for so much.’

He was appointed Chairman of ‘The Twenty Committee, (named after the Roman numerals XX or Double Cross System) whose primary aim was to turn German spies into ‘double-agents’ who worked for the British and although he ran the system, he always credited MI5 with the originality of the idea; it is also widely assumed by many that the writer Ian Fleming (who was in Naval Intelligence during the war) adapted JCM’s surname for the female character of Jill Masterson in his James Bond bestseller,’ Goldfinger’ published in 1959 and played by Shirley Eaton in the film version in 1964.

The Double Cross System first published in 1972

Also, in his role as Chairman he oversaw the cunning and brilliantly executed ‘Operation Mincemeat’ ( now a 2021 film starring Colin Firth and a West End musical of the same name) brought to his attention by Commander Ewen Montague, where the allies used the dead body of a tramp to dupe the Germans into thinking that they were planning to attack Greece and Sardinia rather than Sicily in 1943.

- Operation Mincemeat ‘The Film’ starring Colin Firth 2021

- Operation Mincemeat ‘The Musical’ 2019

Remarkably, the plan worked and is credited as having played a crucial role in the Sicily invasion and is believed to have saved the lives of over 40,000 British servicemen and women.

JCM spent four and a half years as Chairman of the committee and when reflecting on his time in charge he had no doubt of the importance of double-agents and their contribution to winning the war for the allies: ‘We actively ran and controlled the German espionage system in this country and we had learned that these agents could be the most powerful of intelligence weapons and that straightforward espionage was practically valueless during wartime.

Professor Christopher Andrew, author of ‘Defence of The Realm’, published in 2003 believes that,

Thanks chiefly to the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, who provided indispensable support for the ‘Double Cross System’, Britain had better intelligence about Germany during WW2 than any power had ever had about its enemy in any previous war.

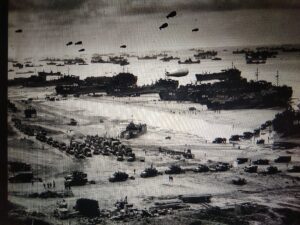

During JCM’s tenure as chairman of the committee, 120 wartime German agents were ‘turned’ by MI5 into double agents, but only when the committee were satisfied that they had been successfully recruited, could they be used to pass over misinformation to the Germans leading to what would become known as the ‘Ultimate Deception’, with the Germans believing that the invasion would take place in Pas de Calais.

With that knowledge secured ‘Operation Overlord’, (the codename for The Battle of Normandy) took place on 6th June 1944 –D Day and resulted in the eventual ‘Victory in Europe’ for the Allies in 1945.

Operation Overlord- The Battle of Normandy D-Day 1944

After the war JCM was asked to write a report on his work and became determined to privately publish a history of his time working for The Twenty Committee, which he called, ‘The Double Cross system in the War of 1939-1945’ and said that he had written it as ‘reference work to be of use in the next war.’

He acknowledged that it was probably impossible to operate a system of this type ever again, but the British Government not surprisingly, strongly objected to this under the terms of ‘The Official Secrets Act’.

They set about destroying the majority of the copies produced, however JCM managed to retain one and subsequently made successive efforts in later years to get the text released for publication and eventually got the book published in the US by ‘The Yale University Press’ nearly thirty years after the end of the war; not surprisingly, it became a great success.

Once the intention to publish became known the British Government abandoned their objections and publication went ahead in 1972; the book’s main argument being that counter-intelligence should be considered a ‘co-equal professional activity alongside espionage.’

However, JCM did not release any information in the book regarding ‘Ultra’ which was the name adopted by the Government for Cryptography (the construction and analysis of protocols that prevent third parties from reading private messages). It was, however eventually de classified in 1974.

He was awarded the OBE in 1944 and at the end of the war JCM returned to Oxford University where he became ‘Provost’ of Worcester College until 1961 and Vice-Chancellor from 1957-1958; he was eventually knighted for his services to British Intelligence, in 1959.

He became President of The Oxfordshire County Cricket Club in 1956 and held the position for ten years devoting much of his time to the affairs of the club helping it through a number of difficulties during his tenure.

In 1975, he wrote his autobiography, ‘On The Chariot Wheel’, where he attempted to sum up the end of his life: ‘

An old friend wrote to me recently and said ’We are all like a river nearing the end of its run, wider in experience, slower in movement and approaching the loss of our identity in the great unknown ocean.

JCM died at the age of 85 in his beloved Oxford in 1977.

John Cecil Masterman (1891-1977):

Sportsman and Spymaster

Source: (c) Charlotte and Stephen Halliday; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:John_Cecil_Masterman.jpg

Article Coyright of Bill Williams

Bill

A very interesting account of the life of J.C.Masterman, truly a man of many talents, particularly in the World of sport.

I enjoyed reading the account very much and noted his connections with the sporting Hartleys of Shipton under Wychwood.

Also, I noted that JCM became Provost of Worcester College, Oxford in 1961, whose excellent Cricket Ground was the home

for the Oxfordshire Constabulary Cricket Club for which I played from 1961 onwards, after I joined the Force in that year.