Introduction

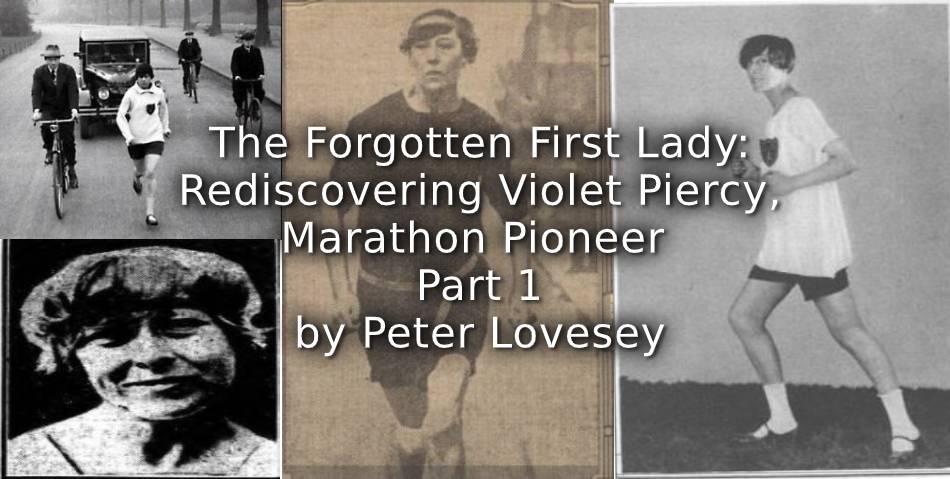

The story of a British woman called Violet Piercy running a marathon in 1926 has been around for many years.[i] However there was no reference to Miss Piercy in the two earliest British histories of the sport, Athletics of Today for Women, by F.A.M.Webster (1930) and Women’s Athletics, by George Pallett (1955). Moreover, the few details to have survived about the run don’t square with known facts. She was said to have run unofficially in the Polytechnic Harriers marathon from Windsor to Chiswick, but Chiswick stadium wasn’t opened until 1938. The date was given as 3 October, whereas the Polytechnic race that year, from Windsor to Stamford Bridge, was on 29 May. Another anomaly is that 3 October, 1926 happened to be a Sunday, when athletics simply didn’t take place in the 1920s. The erroneous information is still disseminated in books and on the internet.

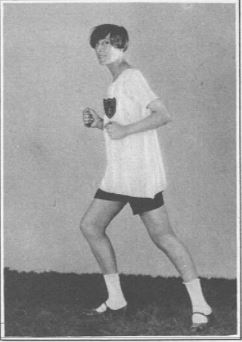

In 2011, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography assessed a number of eminent sports people for possible inclusion in a special update to coincide with the 2012 Olympic Games and Piercy was among them. If, indeed, she was the first British woman to have run a marathon, thirty-seven years before any others attempted such a distance, she had a strong claim to be honoured. But how genuine was her “record”? A request for more information was sent to the National Union of Track Statisticians and a small group of five enthusiasts – Mark Curthoys of the Oxford DNB, Andy Milroy of the Association of Road Running Statisticians, Peter Jefferson Smith of the Clapham Society and Kevin Kelly and Peter Lovesey of the N.U.T.S. – started searches on three fronts: in newspaper archives; in census records and registers; and among veteran athletes who might have remembered Violet Piercy. The story emerged of a pioneering athlete who did, indeed, run from Windsor to London in 1926 and became famous, speaking out repeatedly for women to engage in sport and take on endurance challenges, and eventually completed at least four marathons. She broadcast on BBC radio, was filmed for Pathé News, made headlines in the press and was said to have been watched by thousands when she did her solo runs. Yet within her lifetime she sank into obscurity and was forgotten until the present century except for those few inaccurate details of her first long road run.

This essay reconstructs Violet Piercy’s life story and career and places her in the context of women’s distance running. It also addresses the question of why her strong advocacy for the marathon distance was disregarded by other women for so long.

Violet Piercy

The Sketch – Wednesday 13 October 1926

Historical context

When women’s athletics began to be regulated in the 1920s, long distance running was deemed unsuitable. The maximum permitted distance was 1000 metres. A middle distance event, the 800 metres, appeared only once in the Olympic Games before 1960. The spectacle of exhausted runners in 1928 so horrified the organizers that the event was dropped. The marathon was not introduced until 1984. It was almost as if the sport had to be reinvented, for endurance running was not unknown in previous centuries.

The evidence from literature, vase paintings and inscriptions in stonework indicates that competitive running by women took place in Greece as early as the fifth century BC and for at least a thousand years into the Roman era, but most, if not all of this would have been over short distances.

Probably the oldest traditions of distance running by women as a normal activity, travelling from place to place, come from the Native American civilisation and the Tarahumara of Mexico.[ii]

The earliest documented performances so far traced are by British women, sometimes alone, for wagers, and less often in competition. On Temple Newsam Green, Yorkshire, in 1672, four virgins competed over 2 miles and the winner received a silver spoon, the runner-up a silver bodkin and the third a silver thimble.[iii] In 1712, a woman invited challenges for fifty or a hundred pounds for a race of a mile and a half.[iv] In 1795, a 15-year-old ran a mile in 5 minutes 28 seconds in Kent.[v] Such reports are rare.

Garments as prizes became established in smock-racing, a staple feature of English country life in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These women’s races were often the main attractions of fairs and annual sports held on traditional holidays such as Whit Monday and Midsummer and half a mile was a common distance.[vi]

Endurance walking

In 1809, a bizarre endurance performance by a Scot, Captain Barclay Allardice, caught the public imagination. He walked for 1000 hours (about six weeks) on Newmarket Heath at the rate of one mile each hour, a feat of stamina and sleep denial that numerous others would try to match in the next seventy years.[vii] Women soon appreciated that they were capable of walking long distances, and with more decorum than those who ran for smocks. In 1816 Mary Frith walked 30 miles each day for 20 days,[viii] inspiring Esther Crozier in 1817 to attempt 50 miles per day for the same period. She managed 350 miles and then retired.[ix] Various others took up the walking challenge and in 1844, on a stretch of road near Leeds, a Mrs Harrison, aged 40, became the first of many to complete the “Barclay feat” of 1000 miles in 1000 consecutive hours.[x] In the next forty years attempts were made in Britain, America and Australia. The introduction of the “bloomer costume” (loose trousers gathered at the ankles and worn with a jacket) in 1851 made walking more feasible and there is little doubt that the feat was accomplished by several women, some several times over. They included Emma Sharp in the UK, Margaret Douglas in Australia and Ada Anderson, an Englishwoman in America. Even so, pedestrianism was not without hazards. Emma Sharp in 1864 found it necessary to be accompanied by a man carrying a musket and to carry two pistols herself.[xi] Margaret Douglas was forced to stop after 832 miles when the management of the Alhambra started dismantling the track.[xii] And Emma Gawthorp in 1866 was shot at by her brother-in-law with the words, “I’ll stop her bloody walking. I’ll stop her walking altogether.” He missed, but was brought to court and fined.[xiii]

Amelia Bloomer in her famous costume 1851

Britain’s leading sports newspaper, Bell’s Life, was scathing in its condemnation in a leading article of 1872, “Public Sports for Women”:

We most emphatically say that public contests of strength and wind are not likely to find favour in the eyes of gentle English girls. . . . Public races, whether in the water or on land, are, to our English modes of thinking, only fit for hoydenish lasses at a country fair. It is enough that we have barmaid shows. Moreover, woman is physically unfit for contests of the kind we have mentioned.[xiv]

By the mid 1870s, women’s long-distance walking was known in Britain, Australia and New Zealand and became quite a craze in the United States, usually in indoor arenas, with a variety of extraordinary permutations of the Barclay feat, such as 3004 quarter-miles in 3004 consecutive quarter-hours. Women also took up six-day go-as-you-please races with some success. The press were mostly patronising, but in 1879, the New York Clipper struck a less disapproving note:

Mme Anderson is a good walker, and possesses powers of endurance that are certainly most remarkable in a woman, while of mental force she seemingly has an unlimited quantity.[xv]

Greek Pioneers of the marathon

In 1896 the Olympic Games were revived in Athens and without question the event that drew most interest was a new one, the marathon, won by a Greek, Spyridon Louis, to enormous acclaim. Over the years evidence has emerged of one, and possibly two, Greek women running the same course to prove that they were as capable of finishing as the men. The first reference was in a newspaper in the French language published in Athens, the Messager d’Athenes of 14 March, 1896, and was picked up by a German magazine, Sport im Bild, on 27 March, 1896. “There was talk of a woman who had enrolled as a participant in the Marathon race. In the test run which she completed on her own on Thursday she took 4½ hours to run the 42 kilometres which separates Marathon from Athens. She stopped for about ten minutes halfway, only to suck a few oranges. She is a woman of the people with marked features, of a tough and lively temperament.” The Olympic historian, Karl Lennartz, calculated that the run must have taken place late in February. Recalling the incident some years later, in 1927, the editor of Sport im Bild identified the runner as Frӓulein Melpomene (the Greek muse of tragedy) and stated that she sought permission to run in the official race and was turned down by the Olympic commission, a decision criticised by the Greek newspaper Akropolis.[xvi]

The second reference appeared in the Greek newspaper Asti on 12 April, 1896. Stamata Revithi, a woman of about 30 from Piraeus, the mother of a 17 month old child, ran over the course in 5½ hours on 11 April, the day after the official race. Apparently she had arrived in a cart and camped at the start. She met the local mayor and spoke to journalists. When told that she might enter the stadium after everyone had left, she answered, “Don’t demean us women, we shall always be women, whilst you men have been demeaned by the Americans.” (A reference to the disappointing showing of the Greek athletes over the duration of the games).

It is difficult to know with certainty whether “Fraulein Melpomene” and Stamata Revithi were the same individual, but it does appear that the course was run twice, some weeks before and one day after the official race.

The French marathon runner

In France, the sport of athletics was firmly established towards the end of the nineteenth century, and in 1892 a woman from Brittany, Madame Lemaux, recorded a time of 27 hours 32 minutes for a road run of 147km (91 miles 601 yards) between St Brieux and Brest. France led the way in Europe in organising athletics for women nationally and internationally and even the Great War was not allowed to delay progress any longer than necessary. During the war two women completed the Paris to Rouen walk.

Six weeks before the Armistice, the 1918 Tour de Paris Marathon was held and there was a woman among the runners. She was Marie-Louise Ledru. A photo exists showing her wearing an ankle-length dress and boots, standing at the start with the male runners, a race number attached to her bodice. The course was about a hundred metres longer than the 26 miles 385 yards that had been run in the 1908 Olympics and eventually was standardised and Marie-Louise finished in 5 hours 40 minutes.[xvii]

Marie-Louise Ledru

L’Auto-vélo 1 Ocotber 1918

The Windsor to London ‘marathon’

One positive outcome of the world war was the independence it gave many women, some of it enforced by circumstance, some enthusiastically indulged in as the spirit of a new age. Sport prospered in the nineteen-twenties and for the first time athletics for women was encouraged as more than just the annual school sports day. The leading open club in Britain, the London Olympiades, was founded in 1921. Violet Piercy was a member by 1925, when she is shown in a group photograph. And in the following year she decided to run a marathon.

The summer of 1926 was notable for women’s sport. For the first time, the English Channel was swum, first by Gertrude Ederle and then Amelia Corson. But they were both Americans, and there were understandable mutterings why no Englishwoman had conquered our own stretch of sea. This seems to have been the trigger for Violet Piercy’s first and most famous “marathon”. Although the event was named after the legendary run of Pheidippedes and was devised for the first modern Olympics of 1896, it only became internationally popular in 1908, after the famous “Dorando” incident in the Windsor to Shepherds Bush Olympic race in which the distressed Italian runner was assisted across the line and disqualified. That particular race was also the first measured at 26 miles 385 yards, a distance standardised by the IAAF in 1921.

It appears likely that Violet Piercy believed the run from Windsor to London constituted a “marathon” whichever route she took and in a sense it did because long distance races known as marathons had been run over a variety of distances of twenty miles and upwards ever since the race was introduced. Her confidence was high. She contacted the press and the London Evening Standard reported on 2 October that she was “to begin an attempt to run the Marathon course from Windsor to London this afternoon”. This was the Saturday, one day earlier than most reports give.

Read Part 2 HERE

Article © Peter Lovesey

References

[i] David E.Martin & Roger W.H.Gynn, The Marathon Footrace (Springfield, Ill, 1979) 248

[ii] Gotaas, Thor, Running: a Global History (London, 2009) 270

[iii] Roxburghe collection of English ballads, quoted by Goulstone, John, in Smock Racing: an historical study of a traditional English sport (Bexleyheath, 1997)

[iv] The Post Boy, 27 December, 1712 (Burney Collection)

[v] Ashton, John, Social Life in the Reign of Queen Anne (London, 1883) 244

[vi] Radford, Peter F., Women’s Foot-Races in the 18th and 19th Centuries: a popular and widespread practice, Canadian Journal of the History of Sport XXV, 1994

[vii] Thom, Walter, Pedestrianism … with a full narrative of Captain Barclay’s public and private matches (Aberdeen, 1813)

[viii] Morning Chronicle 12 December, 1816

[ix] Ipswich Journal 8 November, 1817

[x] Leeds Mercury 16 December, 1843

[xi] Telegraph & Argus 17 September, 1964

[xii] Lloyds Weekly Newspaper 18 September, 1864

[xiii] Blackburn Standard 15 June, 1866

[xiv] Bell’s Life in London 17 September 1872

[xv] New York Clipper 4 January, 1879

[xvi] Lennartz, Karl, Two Women Ran the Marathon in 1896, Citius, Altius Fortius, vol 2, no. 1, 1994

[xvii] www.courir-au-nord.fr/news/2855-.html