To read Part 1 of Lisa’s series – Sports Migration during National Socialism: Reasons and Research on the Emigration of Jewish Athletes from Germany after 1933 – Click HERE

As Germany’s – and for some Europe’s – number one tennis player, at the height of his tennis career, Daniel Prenn became the most well-known victim of the anti-Semitic segregation in German sport. Amidst international outrage against his mistreatment, he left Germany for England and found a new home there.

Daniel Prenn, born in Vilnius on the 25th of August 1904 [1] and lived in St. Petersburg for the first sixteen years of his life. During the Czarist monarchy, citizens with a Jewish background were often discriminated against and the Russian Revolution aggravated the situation severely. Therefore, in 1920, Daniel’s family decided to flee to Germany.

Here, in Berlin, Daniel went to high school and later studied at the Technical College Charlottenburg. In 1929, he finished his doctorate as a civil engineer and was employed by the Baukredit Aktiengesellschaft.

At a young age Daniel had already developed an aptitude for many kinds of sports, but tennis became his true passion. Four year in a row, between 1920-1923, he was the National Junior Tennis Champion. During these years he played at Borussia Berlin, before becoming a member of the Lawn Tennis Turnier Club Rot-Weiß in 1926, home turf to many of Germany’s best tennis players.

Daniel Prenn

Daniel’s rise in German tennis can be retraced via the rankings of the Tennis Association, where in 1925 he was 15th before ascending 5 positions each subsequent year. His first major success as an adult was his victory in the 1928 German men’s championship in Hamburg, which elevated him to the very top of the national tennis ranking.

Following this, Daniel was selected for the Davis Cup Team, where he would record his greatest achievements. Playing Britain for a place in the European Davis Cup Final during the 1929 tournament, he defeated one of the world’s leading players, H.W. ‘Bunny’ Austin, thereby securing Germany’s win. In the next year Daniel and female German tennis star Hilde Krahwinkel were able to achieve second place in the mixed doubles at Wimbledon.

However, after these successes the player’s career was interrupted. Daniel had to appear in court and was suspended by the Tennis Federation after allegedly violating amateur principles by receiving rackets as well as money from an equipment company. Even though he vigorously denied the allegations, the suspension was upheld and he missed most of the 1931 season.

During this period the Davis Cup team had not been successful either, until in 1932 Gottfried von Cramm, Germany’s new tennis talent, became part of the team. With him, and Daniel returning, the team won against India, Austria and Ireland in the tournament first rounds, before meeting England in the semi-final in July. Once more, Daniel was able to succeed against England’s top players and led Germany to the European Zone final, where they won undefeated against Italy. In the Inter-Zone Final, the team lost closely to the US. But despite this defeat, Daniel was at the hight of his career. American Lawn Tennis magazine called him “Europe’s number-one man” and in the international tennis ranking he reached the top ten, being the first ever male German player, at no.6.

At this most successful time of his career and internationally renowned, Daniel became a prominent casualty of the Nazis’ sports politics. The Tennis Federation declared in 1933:

“The nomination of non-Arians for representative matches (national competitions, Davis Cup, team games) and official association matches is not permitted.”[2]

The decision led to worldwide objections, including the Swedish King Gustav V. Adolf, who played a show match with Daniel in Berlin, and his former opponents ‘Bunny’ Austin and Fred Perry, who wrote in an open letter to the English Times:

“We cannot but recall the scene when […] Dr. Prenn before a large crowd at Berlin won for Germany against Great Britain the semi-final round of the European Zone of the Davis Cup, and was carried from the arena amidst spontaneous and tremendous enthusiasm. […] we view with great misgivings any action which may well undermine all that is most valuable in international competitions.”[3]

Shortly after the exclusion from the association he had successfully represented, Daniel and his wife Charlotte decided to leave Germany for England. In an interview the sportsman gave to a British newspaper soon after arriving in England, he addressed his stay in the country as a ‘tennis holiday’. Indicating that, at first, he did not intend to immigrate to the country permanently, because he was not only active as a successful tennis player:

“‘I am still engaged as an engineer in Germany, and when I have finished my holiday, which is to be a tennis holiday […] I will go back, probably to Berlin. But my plans at the moment are unsettled.’”[4]

That Daniel eventually settled in London indefinitely was influenced by two factors which, in his case, alleviated the rigorous immigration restrictions of the UK. Firstly, his training as an engineer put him in a privileged position regarding employment constraints which were generally aimed at securing jobs for Britons first and deterring immigrants from taking up work. However, after the impact of the economic crisis had lessened, the demand for technical goods and services increased. Because qualified technical and engineering personal was scarce in the UK, the immigration of engineers was embraced and supported.

Secondly, Daniel had close connections to Marks & Spencer owner Simon Marks, a fellow tennis enthusiast. This relationship facilitated the British policy of sponsorship by an acquaintance. In 1935, Marks also aided Daniel with the establishment of his own company, Truvox, a manufacturer for loudspeakers. This friendship to the Marks and Spencer head pervaded throughout his life.

Daniel (right) with fellow players at a tennis party in England

Following his immigration, Daniel first settled in London where he later started his own company in Kentish Town. He also found a home in some local sports clubs, becoming a member of the esteemed Queens Club London, resembling his former Berlin Club. Daniel, as well as his wife Charlotte, also joined the Anglo Russian Sports Club, another elitist institution and an establishment for upper-class Russian exiles in the UK.

In 1933 Daniel and his fellow German-Jewish émigré Martha Jacobs, competed for the British Team at the Maccabiah, the Jewish Olympiad, in Prague. The two athletes received a great deal of attention upon announcing their participation, especially because they were employed as figureheads by the British organisers who tried to recruit sportsmen but especially -women for the team:

“Lord Melchett […] made an urgent appeal to Anglo-Jewish athletes to participate in the games at Prague. It was more than ever essential, he said, that British teams should be proportionally represented in the Jewish international athletic gathering […]

Already several Jewish athletes in this country have agreed to join teams for the Prague Festivals. Prenn, the international tennis champion, Martel Jacob, the Champion javelin and discus thrower […] are among them.”[5]

Despite his attendance of the Maccabiah and other tournaments, it has often been falsely stated that Daniel’s career finished upon settling in the UK. However, he still competed for several years – even though not on the level he had reached in 1928-1933 – and only retired from professional tennis in 1939. His successes at minor British tournaments are very well documented in British newspapers. Consecutively between 1933-1935 Daniel won the Scottish Lowlands Tennis Championship, but he also attended major tournaments, such as Wimbledon. In 1937 he reached the fourth round in the men’s singles and moved to the semi-final in mixed doubles with his British partner Evelyn Dearman.

However, not these wins were not the prime concern of the press at the time, rather than his nationality. A sub-headline in the Dundee Evening Courier prior to Daniel’s fourth round single match read:

“Frankie Parker meets ‘No nationality’ Man”.[6]

In 1937 Daniel was no longer listed as a player from Germany, instead he had no nationality indicated in the official registration. The following year, the Belfast Telegraph headed an article:

“Lawn Tennis Star Wants to Become British”.

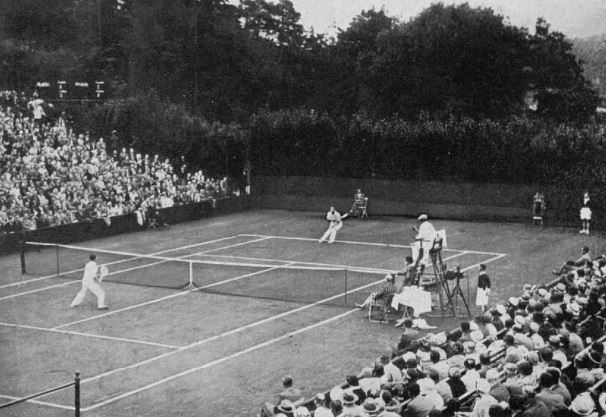

Davis Cup 1932 Austin v Prenn

Source: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News – Saturday 16 July 1932

Daniel’s application for naturalisation as a British citizen was eventually granted in April 1940. He was one of the few lucky exceptions, as very few migrants were naturalised at the time and citizenship proceedings stopped entirely by June 1940 following the international developments. Daniel and his wife had also been exempted from internment in 1939 while nearly all German refugees in the UK where interned as “Enemy Aliens” with those who were excepted having to prove their value for armament. Due to his engineering education and technical knowledge, Daniel was once more one of the fortunate exceptions. An obituary after his death refers to him as “a valued defence contractor during and after the war.”[7]

Charlotte and Oliver

Source: Tatler – Wednesday 07 December 1938

Daniel’s wife Charlotte had welcomed a son, Oliver, in September 1937. Twenty years later, after separating from Charlotte, Daniel had a second son, John, with Maxwell A. Taylor, with whom he lived until her early death at the age of 42. In 1980 he remarried Veronica Kristi Hauge, a movie producer.

Daniel’s personal life after his tennis career was set. Even after retiring from professional sports, he did not disappear from the public. His company was successful, and several business acquirements had made Daniel a wealthy Briton. Contemporaneously, sport remained a constant in his family’s life. His son Oliver followed in his footsteps, winning the Wimbledon Junior Championship and John became Rackets World Champion in 1981 as well as 1986. Another sport Daniel became passionately devoted to was horse racing, having several own runners. He sponsored the prize money for different races, including the Daniel Prenn Royal Yorkshire Stakes in York – which remained dedicated to him well beyond his death.

Daniel Prenn died on the 3rd of September 1991 in the United Kingdom.

Even though in past decades the stories of Jewish athletes from Germany and their fates during National Socialism have deservedly and necessarily become a focus of both research and remembrance, Daniel’s eventful life as well as his achievements have not yet been commemorated nor thoroughly studied.

Article © of Lisa Jenkel

Read Part 3 – Gretel Bergmann ~ An International Olympic Contender~ The ‘Bitter Awakening from the Wonderful Dream’ of Attending the Olympic Games – Click HERE to read

References

[1] Different information regarding Daniel Prenn’s date of birth have been found in the sources, e.g. 7th October 1904 (Ayres Tennis Almanack 1939), 7th September 1904 (Who’s who in Tennis) or 25th August 1905 (Jutta Deiss „Der Emigrant,” see below), however, in official documents the 25th August 1904 is repeatedly stated as the date of birth, therefore, this date has been assessed as the most reliable.

[2] Quoted and translated after: Hans-Jürgen Kaufhold, „Vom Licht ins Dunkel,“ in Tennis in Deutschland: Von den Anfängen bis 2002, ed. Ulrich Kaiser (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 2002), 135.

[3] Quoted after: Hans-Jürgen Kaufhold, „Vom Licht ins Dunkel,“ in Tennis in Deutschland: Von den Anfängen bis 2002, ed. Ulrich Kaiser (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 2002), 136.

[4] Sheffield Independent, Tuesday 06 June 1933, page 9 – “D. Prenn in England”.

[5] The Jewish Chronicle, Friday 28 July 1933, page (?) – “Maccabi Festivals Transferred to Prague”.

[6] Dundee Evening Telegraph, Friday 25 June 1937, page 9 – “Wimbledon Fifth Day”.

[7] The Times, Wednesday 18 September 1991, page 18 – “Daniel Prenn”.

![The Eternal Seconds of Italian Women’s Athletics:<br>The History of Gruppo Sportivo La Filotecnica [Milan, 1935-1943]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/PP-banner-maker-3-440x264.jpg)