The development of Llandudno was planned in 1849 on land owned by the Hon. E.M.I Mostyn.1 By 1860 the town had ‘risen out of obscurity.’ Cottages had been replaced by modern buildings. J.Hassan states this as a process of ‘anglicisation’, the historiography on the growth of North Wales is still limited.2 M.Booth’s well-known work highlights how theatres can be used to understand London society. This study argues Llandudno’s theatre development is a window to the town’s rapid transformation.3

Transport and Theatres:

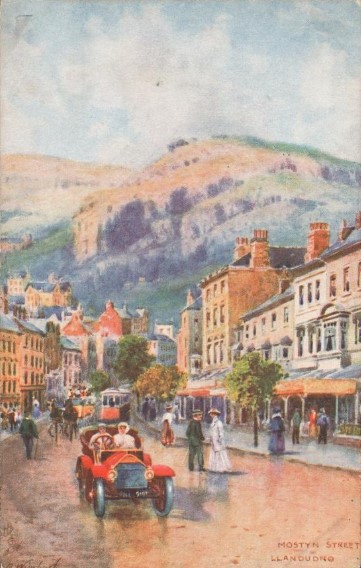

The advancement of transport during the nineteenth-century influenced the rapid growth in theatre construction. The railway station was opened in October 1858 along Vaughan Street, which is still the functioning station’s location today. The local Newspaper the North Wales Chronicle, in 1866, kept records of the visitors to the town and the enthusiasm to improve public facilities and boost tourism.4 A high proportion of visitors came from the neighbouring industrial cities, Manchester and Liverpool. Steamships alongside the railway became accessible as early as 1840, as it transported visitors to enjoy Llandudno’s sea-bathing health benefits. The Liverpool and North Wales steamship company which ran trips along the North Wales Coastline included the rivalling larger north wales resort of Rhyl. By 1907, ‘the Freeman’s Journal ‘states a ticket was ‘remarkably low cost and it could come as a package deal’.5 From the handbooks from the time, J.Hicklin in 1858 explains the advancement of mobility throughout the town was due to cheap fayres on coaches that travelled from the station to the theatres and shops along the high street, Mostyn street. Hicklin explains how the Llandudno Improvement Act of 1854 meant ‘bye-law regulations’ could be put on Hackney coaches that transported people around town. The coaches served a purpose not only to transport people to and from the theatre safely to catch the train home. The Savoy Theatre built 1914-1987 and the Palladium built 1920-1999 were examples of theatres that fitted to the tourist landscape that prioritised shopping and boosting the economy. Postcards reflect the importance of carriage transport given how crowded Mostyn street was, this being a perfect location for the theatres to be noticed.6

H.B. Wimbush, ‘Mostyn Street

Llandudno printed between 1903 and 1959’, Postcard.

Theatre Investors and the Seaside Landscape:

Whilst the high streets were developing, the railway paved the path for investors from Birmingham to find a potential for Llandudno’s seaside landscape.7 From 1840-1860, the sea was a fascination with the ‘middle classes’ for health benefits. Welsh heritage was pressured as the land was leased to make way for ‘anglicisation’ by investors.8 Following a period of financial difficulty for theatres from the 1815-1860s, there was a ‘building boom’ particularly in large developed cities such as London and Birmingham. West End shows had gained respectability, investors were now looking for potential locations that could make profits from beautiful landscapes.9 The Grand Theatre built 1901-1980 is an example of bringing the West End to the sea, ‘the Llandudno Advertiser ‘ in 1901 stated that ‘Mr. Milton Bode will give the best plays from London theatres.’ The Grand Theatre’s architecture reflected wealth influenced by the grandeur in London’s theatres, ‘the Llandudno Advertiser’ highlights that the Theatre was to be fitted with electric lighting, heating, and fire precautions. 10

Railway Networks and Llandudno Advertising:

Package deals were usually advertised underneath play advertisements in London newspapers to create a link between seaside holidays and theatre shows. Advertising was arguably a method that aided the popularity of the theatres in Llandudno that were located on the promenade by 1910.11

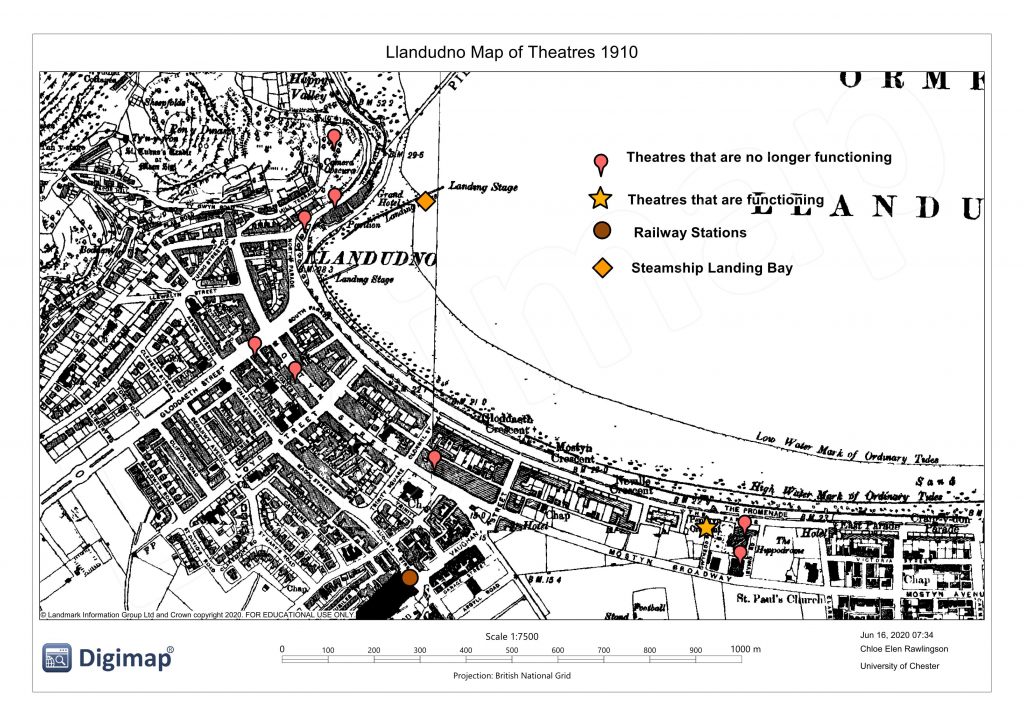

Map of Llandudno’s Theatres, 1910

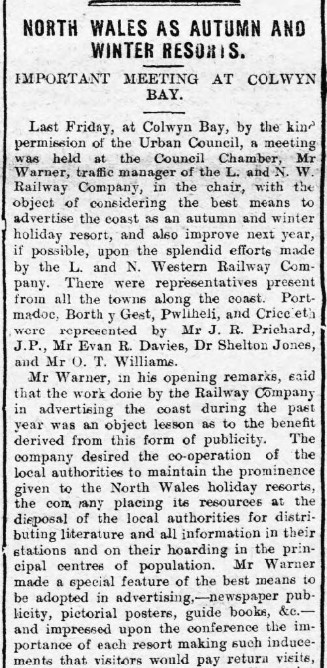

In September 1909, The North Wales Company established the North Wales Advertising Board which represented the pooled resources of 21 resorts. The railway agreed to distribute the board’s materials and guidebooks across its networks. The NWAB in 1909 was spending £3,000 to £4,000 on advertising Wales. The LNWR by 1910 agreed to handle all advertising of North Wales in London, the overall message was to promote the region as a place of ‘health, leisure, and residency’.12 Whilst advertising was creating an attractive image to invite visitors, J.Lawson-Raey argues there were some failures in their campaign for example in 1891 the station was rebuilt in Ruabon Brick, reflecting the town’s welsh resources. The result was functional rather than impressive inspiring arrivals with little sense of excitement.13 Birmingham New Street station in comparison, had the world’s largest glass roof at the time.14

‘North Wales as Autumn and Winter Resorts’ <br< Source: North Wales Express, 3 September 1909

Theatres and the Working-class:

Social reform also aided the need for theatres. Living costs declined from 1870-1900, as Britain was importing food cheaply from Europe and there was a rise in wages. The 54-hour working week was gradually shortening and the introduction of Bank Holidays meant the working-classes had more time for leisure.15 The study by H. Shapayer Makov highlights the importance of day trips to the seaside as part of workday trips. The police force in England by 1870 consisted of 43,000 employees, it was a good example of a public institution that combined work and leisure by providing employees with entertainment.16 Booth explains that theatre is a window into societal life, the rhetoric of laissez-faire in Victorian Britain, many employees retained an older conviction that the free time of workers was not their own, this should be supervised.17 The Pier Pavilion Theatre built 1884-1984 backed onto Llandudno’s pier. The Pavilion was popular at first as a music hall for the Manchester police force day trips, but later plays were enjoyed. By 1886 the Pavilion attracted the working-classes for drinking which caused tensions with the police workers who had pressure to be a role model for citizens as part of their career.18

Summary:

Theatres reflect the demands of society, they brought economic prosperity to Llandudno and social development. A side effect was the damage caused to the town’s Celtic heritage. Further is needed into why so many of these theatres disappear by the 21st century, Llandudno’s story is that a ‘country is never just an economy’.20

Article © Chloe Elen Rawlingson

References

[1] D.A.Halsall, and F.A.Montgomery, ‘Refocusing on George Barrow (1803-81): An Eccentric View of Wales?’ Geographical Association, 88(2003) 117-123 at p.121 <https:// www.jstor .org/stable/40573830> [Accessed: 27 May 2020]

[2] J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps, Notes of Family Excursions in North Wales, taken chiefly from Rhyl, Abergele, Llandudno, and Bangor, (London,1860) at p. 67. Located at Internet Archive: <https://archive.org/details/notesoffamilyexc00halliala/page/n3/mode/2up> [Accessed: 1st May 2020] ; J. Hassan, The Seaside, Health and the Environment in England and Wales since 1800, (Oxon: Routledge,2016) at p.5

[3] M.R. Booth, Theatre in the Victorian Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991) at p.9

[4] J. Lawson-Reay, Llandudno: History Tour (Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing Ltd, 2015) at p.5; ‘Special Edition of the North Wales Chronicle: Original Directory and List of Visitors’, North Wales Chronicle (Saturday December 16th 1865) at p.9. Located at The National Library of Wales. < https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4448313/4448322/90/LIVERPOOL> [Accessed: 21st May 2020]

[5] D. A. Turner, ‘Delectable North Wales and Stakeholders: The London & North Western Railway’s marketing of North Wales, c.1904–1914’ Enterprise & Society, 19 (2018) 864-902 at p.879 <doi:http: //dx.doi.org/10.1017/eso.2017.70> [Accessed 14 May 2020]

[6] J. Hicklin,The Hand-book to Llandudno and it’s Vicinity, (London: Whittaker & co, 1858) at p.138 < https://archive.org/details/handbooktollandu00hick/page/n7/mode/2up/search/theatre> [Accessed: 15th May 2020];

H.B. Wimbush, ‘Mostyn Street, Llandudno’, (Raphael Tuck & Sons:The Newberry Library, 1903-1959) Located at Internet Archive: <https://archive.org/details/nby_LL8429/page/n3/mode/1up> [Accessed: 20 May 2020]

[7] Hicklin, p.9

[8] Hassan, p.5

[9] Booth, p.7

[10] ‘The Grand Theatre’, Llandudno Theatres <www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/LlandudnoTheatres.htm> [Accessed: 2 May 2020]

[11] Turner, p.895; Rawlingson, Chloe “Map of Llandudno’s Theatres 1910” JPG Map, Scale 1:5,000 (1910) , using Digimap Historic Roam,< https://digimap.edina.ac.uk/roam/map/historic> created 16 June 2020

[12] Turner, p.875

[13] Lawson-Reay, p.5

[14] ‘The History of Birmingham New Street Station’ Located at <https://www.networkrail.co.uk/who-we-are/our-history/iconic-infrastructure/the-history-of-birmingham-new-street-station/>[Accessed: 12th June 2020] ; ‘North Wales as Autumn and Winter Resorts’, North Wales Express (3rd September 1909) p.5. Located at : The National Library of Wales < https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3572698/3572703> [Accessed: 12th June 2020]

[15] Booth, p.10

[16] H.Shpayer-Makov, ‘Rethinking Work and Leisure in Late Victorian and Edwardian England: The Emergence of a Police Subculture’, International Review of Social History, 47 (2002) 213-241 at p.214

[17] Booth, p.9

[18] Shpayer-Makov, p.218

[19] P. Borsay, ‘A Room with a View: Visualising the Seaside c.1750-1914’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 23 (2013) 175-201 at p.183 < https://doi.org/10.1017/S008044011300008X > [Accessed: 20May 2020]

[20] W. Ashworth, ‘The Late Victorian Economy’ Economica, 33 (1996) 17-33 at p.28 < https://ww.jstor.org/stable/2552270> [Accessed: 27 May]; T. Gale, ‘Modernism, Post-Modernism and the Decline of British Seaside Resorts as Long Holiday Destinations: A Case Study of Rhyl, North Wales’ ,Tourism Geographies, 7(2005) 86-112 at p.107