In January 1912, the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA), having decided to appoint ‘a supervising trainer’ and subsidiary trainers prior to the Stockholm Olympics, asked F. W. Parker to accept the position of Chief Athletic Advisor. In March, they accepted his nominations for trainers, selected from a ‘very large number of applications’, including Alec Nelson, William Cross, Bill Thomas, and one S. Fritty. Parker considered Fritty ‘one of our best trainers and if not required for Reading would advise his appointment to one of the London tracks’. While the life courses of many trainers are gradually being uncovered, Fritty has long eluded identification but now, thanks to the painstaking efforts of Margaret Roberts, we know that ‘Fritty’ was not his real name. In fact, he was Samuel Greenhill, a draughtsman who always used the pseudonym ‘Fritty’ in his engagement with late Victorian and Edwardian sports. The critical confirmation comes from Greenhill’s will, which begins: ‘I, Samuel Greenhill of 38 Villiers Road Southall in the County of Middlesex, Trainer, known as Samuel Frilty (sic)…’.

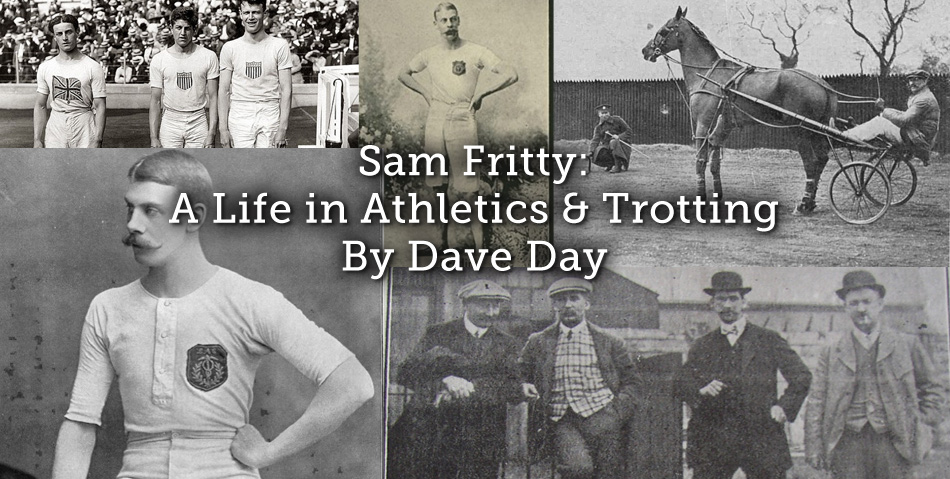

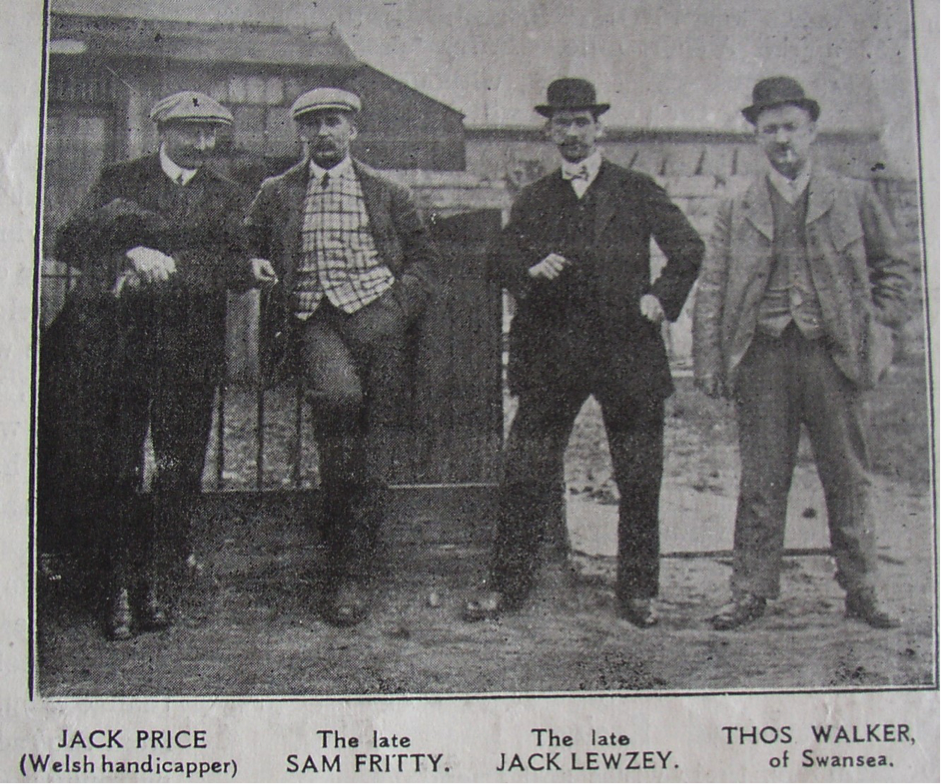

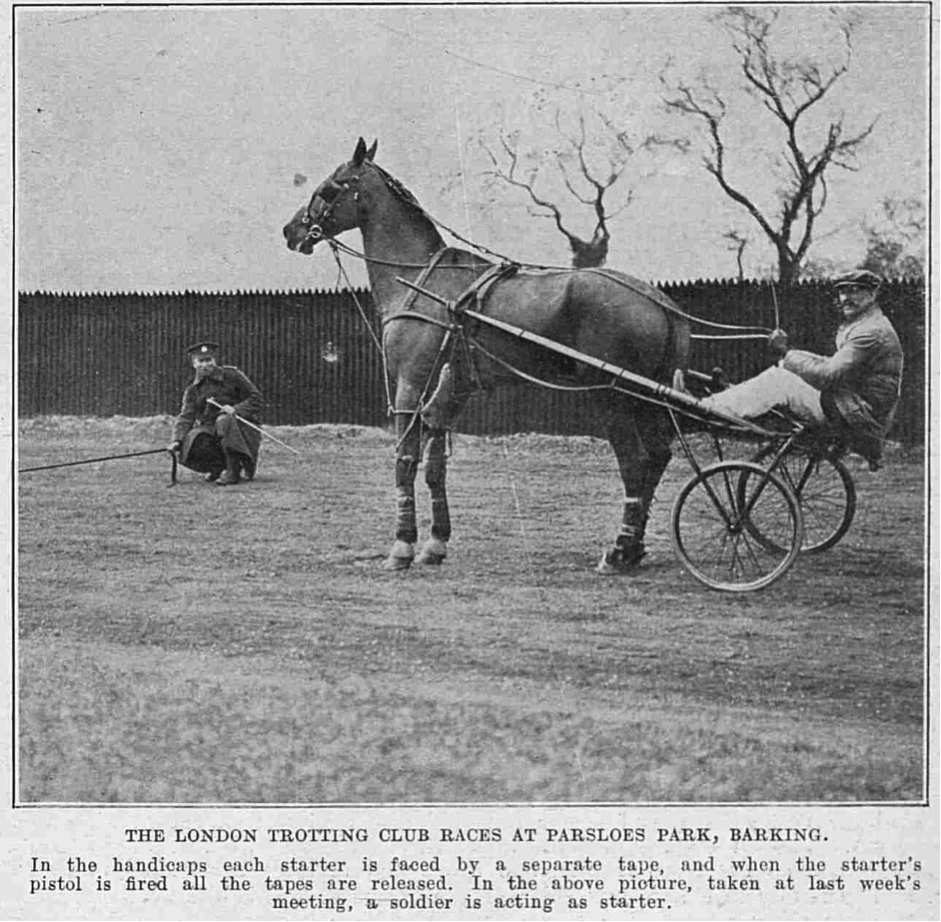

- Fritty and Trotting Acquaintances. Trotting World, 1931

Life Course

Sam’s parents, Samuel, a coachbuilder, and Harriet Greenhill, were married in 1865 and the couple had had four children, including Samuel (5) and Alex (4), by 1871. The family were in Westminster in 1881, and the fifteen-year-old Sam and his younger brother Alex were both clerks, although Alex enlisted in the army in May 1884. Describing himself as an unemployed draughtsman in 1891, twenty-five-year-old Sam was living with Ellen and son Samuel at 16 St Martin’s Street in the Strand. Ten years later, Sam was an ‘engine draughtsman’ and the 1902 and 1903 electoral registers show him living at 74 Norry Street, Putney. The family had moved to Wimbledon by 1911, by which point the forty-five-year-old was a self-employed draughtsman. In the intervening period, he also ran a business as a turf accountant in Haymarket. Sam died in 1922. In April, Trotting World reported that the ‘popular Greenford trainer’ was in a precarious condition suffering from tetanus, possibly brought on by a fall suffered when driving My Bob on Good Friday when he had split a finger badly and probably picked up the infectious germs from the track. The 1922 national probate calendar recorded that Samuel Greenhill of 38 Villiers Road, Southall, Middlesex had died on 29 April at St. George’s Hospital, Middlesex, leaving an estate worth £3,643 10s 6d. A subsequent notice in the London Gazette in February 1923 repeated Sam’s occupation as a ‘Trainer’.

Athletics

Throughout his life, Sam was involved in sport, including acting as a boxing second and competing at ‘ping pong’, but it was in athletics and trotting that he gained prominence. By August 1886, he was already acting as an athletic trainer. When Major Crackles and Fred Cairns, who won by a yard, raced 120 yards for £4 at the Prince of Wales’s Grounds, Bow, both men were in good condition having each had the services of a ‘well-known pedestrian’, S. Fritty for Cairns and T. Townsend for Crackles. Ten years later, when Anstead was preparing for his four-mile race with Bacon for £200 he went to Sandhurst for seven weeks to train with Sam in ideal training quarters which included the use of the college gymnasium and track. Anstead was in ‘good hands’ and having undergone thorough preparation was ‘wonderfully fit and well’, although Bacon won in 20min 34 4-5 secs.

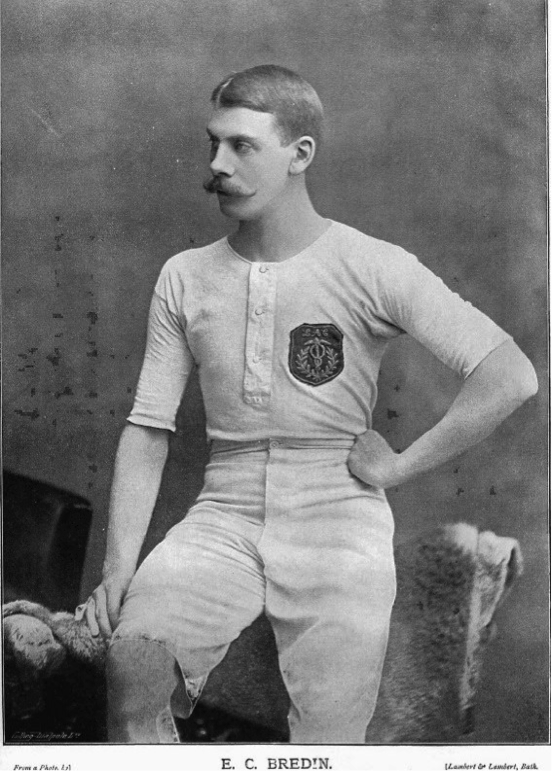

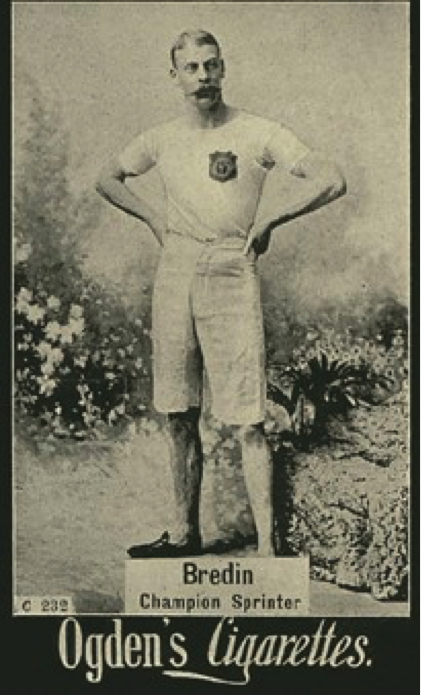

- Bredin – Amateur turned Professional

Despite the increasing power of the AAA, professional trainers like Fritty were always in demand. When E.C. Bredin, a leading amateur, turned professional in 1896, he observed in the Pall Mall Gazette that ‘I believe that with professional training I shall do much better than anything I have done as an amateur. Other men have improved considerably. As an amateur I never trained properly. Now I am having a thorough preparation have given up smoking – a thing I never did as an amateur – and have engaged a professional trainer, Sam Fritty…he has had a lot of experience and I am quite satisfied with the improvement I have made during the short time he has been attending to me’. Observers agreed, noting, for example, that Bredin had improved his start since he had been with Sam. Although Bredin publicly expressed doubts in 1897 that he might not be able to ‘stay the full quarter’ because Sam never let him run more than 400 yards in training, commentators described this as a ‘try-on’ and believed, rightly as it turned out, that, ‘with the enormous advantage derived from professional training’ he would beat Mills in his forthcoming match. Following his defeat of Mills, Bredin stayed at Rochdale before going on to race A.R. Downer over 400 yards for £100 at Bolton on 6 February. He arrived on Saturday morning accompanied by Sam, and, after winning the toss, took the outside station, thought by some to be an error of judgement, although one observer pointed out that he was an experienced runner and that Sam Fritty was an authority on such matters. In the end, Downer won by a yard and a half.

- Bredin in Ogden’s Cigarette Card Series

On Saturday 1 May, Bredin and Downer again decided a quarter of a mile match at Rochdale. Previewing the contest, one writer noted that generations of professional runners and trainers regarded the ‘after dinner nap’ as one of the most essential parts of the preparation for an important race. Experienced trainer Sam Fritty was an ‘upholder of ancient traditions in this respect’ and an hour’s sleep after dinner was part of Bredin’s daily routine. The ex-amateur champion’s preparation was conducted upon ‘strictly common-sense lines’ in other ways. Although, in company with his trainer, Bredin visited the Palmer track twice a day, he seldom ran a quarter of a mile, but indulged in sprints of 100 yards or so and ‘good pipe openers’ of 600 yards or half a mile. The sprints improved his speed while the longer distance runs improved the stamina necessary for the finish of a fast run race. Owing to the judicious manner in which he was being trained, Bredin was likely to be in better condition on May 1 than he had ever been for any of his previous engagements. Immediately prior to the race, there were concerns that Bredin had gone a ‘trifle stale’, although Sam remained perfectly satisfied with his condition and, in the end, although Downer won easily by three yards in 49 5-8secs, Bredin apparently looked much fresher. Bredin raced Downer again on March 5, 1898, after taking his ‘spins’ at Stamford Bridge. He had visited the track every week during the winter so he needed little extra training and he was once more under the care of Fritty, who had just recovered from a severe illness. A year later, there was a great interest in the half-mile race for £100 between Bredin and G.B. Tincler at Rochdale on 18 February, Bredin winning by half a yard after training at home with Sam.

- Willie Applegarth, Donald Lippincott and Ralph Craig, 1912

Fritty subsequently worked with one of the leading British sprinters of the Edwardian period. At the AAA Championships in June 1912, the winner of the 200 was Willie Applegarth, whose success was due ‘to the judgement of Sam Fritty, who has done well by his charge’. The Athletic News remarked later that year that Applegarth was still only twenty-two and that if he wintered well and if Sam still had ‘the care of him next year’ long-standing amateur records would be beaten. Other commentators were equally complimentary about Sam’s work, noting that the way in which Applegarth had kept his form reflected the greatest credit upon Fritty. It was also pointed out that Sam was an Englishman born and bred. Had Applegarth been managed and trained by an American there would have been ‘loud shouts all round’ but the way in which Sam had done his work supported arguments that Britain had trainers good enough for ‘anything or anybody on this side of the Atlantic’. Sam’s expertise was clearly recognised by the AAA. After utilising his expertise in preparing for Stockholm they appointed him again the year after the Games to attend Stamford Bridge to coach elite athletes on a daily basis.

- Possibly Fritty. Illustrated Dramatic and Sporting Times, 29 April 1916

Trotting

By the start of the twentieth century, Sam was equally well known and respected in trotting circles, as an owner, driver and trainer. In August 1903, it was reported that a match for £400 between Sam’s own horse Gamecock and J. Andrews’ Grace Greenlander had been ratified. Gamecock was being trained in Essex and the five-mile match was due to take place on September 7 at Parsloe Park, Dagenham. In August 1903, another five mile scratch race at the same track saw the British record broken by G.T. Tuckwell’s Uncle Bill when it beat Gamecock by a neck in 13min 10 3-5secs. A year later, Gamecock won the Mile and a Half First Class handicap at Belhus Park, off 185 yards, in 3min 30secs. Gamecock also featured in races at Imber Court in 1905, and results lists throughout the pre-First World War period indicate that Sam not only drove for himself but for other owners as well. This could be somewhat hazardous. In September 1908, the Sporting Times noted that Sam Fritty, the ‘popular and highly-respected driver’, had met with an accident and was to be given a benefit, including the entire gate from a special meeting held in October. All the officials were giving their services free and there was already a good subscription list. Ultimately, as noted earlier, another trotting accident led to Sam’s death in 1922.

Postscript.

Research into the hidden histories of trainers like Fritty never completely ends and there are always questions to be resolved. References to Sam describe him as the ‘once well-known and speedy pedestrian’, and the ‘old sprinter’ but all of the pedestrian sprint events recorded by Bell’s Life in which the competitors include a ‘Fritty’ between May 1884 and April 1886 always refer to ‘A. Fritty’ not ‘S. Fritty’. Was this brother Alex or was Sam playing another game in using his brother’s initial? Another conundrum, another quest ahead.

Article © Dave Day

I doubt the horse race was over 5 miles, that’s 8km in 13 minutes 10 seconds, 11.65 meters per second. .

All well and good if it was.

3 miles is 4,800m = 11.65 meters per second is a great speed circa 41 to 42km per hour for 3 miles is an elite Standardbred time in 2018.

Horse could be part Thoroughbred.

Hmmmm.i would like to know.

International Standardbred Trainer.

Thanks Andy – I have sent you the copy of the relevant article from The Sporting Life and as you will see the figure quoted in this article are correct according to the newspaper at the time. Whether the reporter at the time was correct in his reporting is another matter of course!!!

Kindest

Margaret (Editor in chief, Playing Pasts)

Margaret Roberts. I can’t thank you enough for all the information you unearthered about Sam. Greenhill.

His name has come down the generations in my family as there were strong links with his wife (they were not married) and my father Alfred and his sister Ellen.

Sam & Ellen had a mutual friend with my family in Julia Sherwood who was the unmarried mother of my father Alfred and his sister Ellen(ettie)

My grandparents Louise and Alfred Dunning were given Ettie to bring up but at the age of two she was taken away from them and given to the Greenhills.

Julia went on to have another baby (boy) and she gave him to my grandparents to bring up.

Ellen (ettie) was brought up as a daughter of the Greenhills but married a John B Chalmers in 1911 and emigrated to N.Z where she died within 5 weeks of being there.

My father Alfred was a great sprinter and I have photos of him in his youth with prizes won, I wonder if he was trained by Sam.

I tell you all this because my Father did not know that Ettie was his sister until late in life and we will never know who the

Father was as Julia never revealed it. The family always wondered if it was Sam.