To read the first parts of this series –

Click HERE for Part 1 and HERE for Part 2

The story of two editions (1933 and 1934/1935) of the Mitropa Cup for national amateur boxing teams are revealing of how problematic was a shared international organization of a sports tournament, when Germany entered the scene, moreover Nazi Germany which had a plan and a precise strategy of affirmation through sport.

The bilateral meetings between Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia in boxing, much loved by the youth of these countries, had arisen since the early post-war years. Often the meetings had also opposed regional selections of these countries, without particular problems.

After a first attempt to launch the tournament that was aired in 1930, on 12 November 1932 in Vienna was signed the agreement and at the beginning of 1933 Mitropa Cup of amateur boxing started effectively. Alongside the three classic nations of Central Europe, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, also selection of Bavaria took part. Bavaria boasted a strong representative, which often provided elements to the German national team. Certainly, Bavaria’s participation evoked memories pleasing to the Austrians. At the time of the Empire, but also during the Interwar years, strong was the connection between the Bavarians and the Austrians, in the majority Catholics and united by strong ties in the world of art, music and traditions.

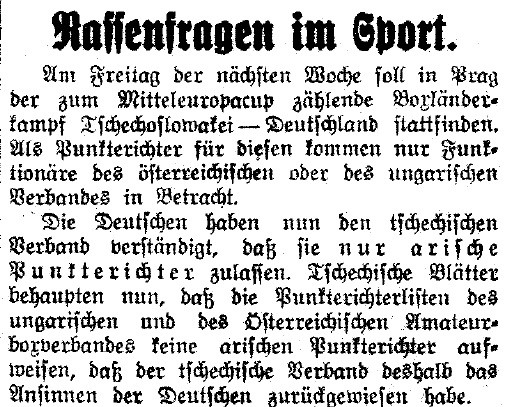

- From Kleine Blatt, 19 November 1934. Racial prejudice enters in Mitropa Cup

Artur Kankovsky, the Czechoslovakian who held the office of general secretary of the international amateur boxing federation (FIBA), was a great patron and a guarantee element of the tournament.

The Tournament developed according to the League system with home/away matches and a final classification. The weight classes were the classic ones : fly, bantam, feather, light, welters, middle, lightheavy and heavy. Four of the scheduled matches were refereed by one delegate from one nation and the other four by one representative from the other. Head referee was a representative of another Mitropa Cup nation. The winning boxer secured two points to his team, in case of a tie there was a point each. The forfeit was punished with 16 to 0.

Bavaria started brilliantly the Tournament by beating Austria in January and defeating on 5 May in Munich, in front of 3000 spectators, the favorite Hungary, thus placing a candidature on the final victory.

The controversies that emerged concerned the question of the citizenship of some boxers, such as the Vienna-born Hawelka, resident in Prague and member of Czechoslovakia.

But, in the continuation of the Tournament, political conjunctures determined the interference of Germany and its boxing authority. The Nazi ascent had accentuated the diplomatic divisions between Germany and Austria. Hitler had never made any secret that one of his main objectives was the Anschluss, that is, the reunion between the two countries. Germany had begun a strategy of infiltration and espionage, but also of attacks and disturbing actions. In July, a bombing attack in Vienna had provoked a strong reaction from the Austrian regime and its sport environment declared a boycott. Austria, the great power of weightlifting, missed voluntarily the European Championships in Essen. Germany responded by withdrawing Bavaria from the scheduled meeting of boxing Mitropa Cup against Austria.

-

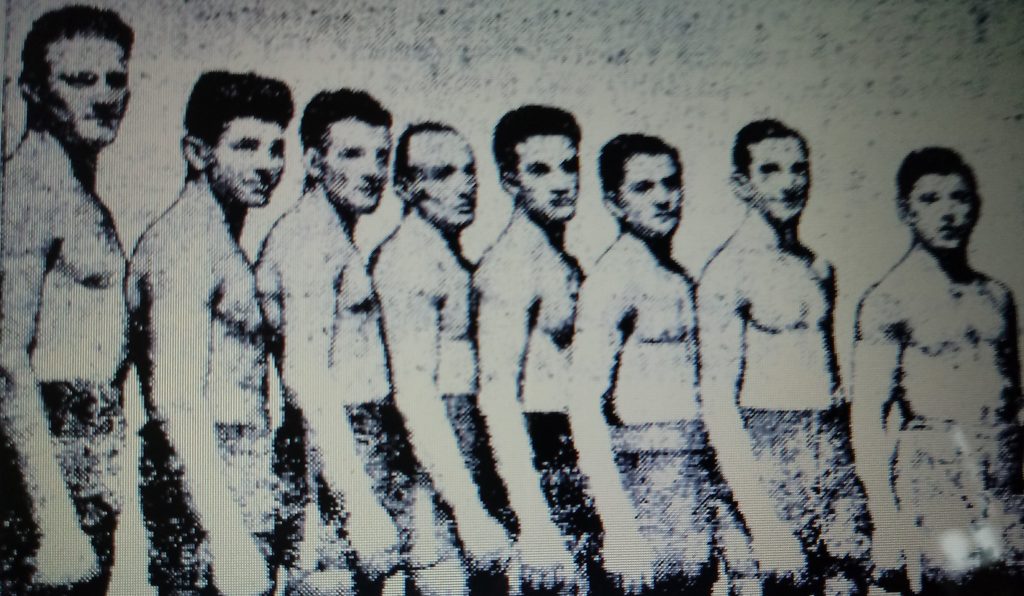

National team of Austria in 1934.

From left to right (from heavy to fly), Martinek, Weichardt, Führer, Weilhammer, Swatosch, Jaro, Illichmann, Schlänger.

The German federation at this point prevented Bavaria from any meeting and Hungary thus won the Cup for 1933. Kankovsky’s role was decisive; he could not allow a clear rift between FIBA member nations. The Tournament of 1934-1935 was then announced of a high level of participation and quality. Romania, Poland and Italy announced their membership. Only Poland, whose competitive level was soaring, then confirmed its commitment. A bit later, Germany’s request came, to which no one could say no. The referee triad became completely neutral.

On April 18, 1934, in Budapest, the second Tournament began with Hungary’s victory over Poland by 10 to 6. Quickly, Germany emerged as the strongest nation, winning all the scheduled matches with great incisiveness. The two meetings with Austria remained on paper. On 25 July, an attack of clear Nazi origin had killed the Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss. The Austrian boycott was more in force than ever and negotiations for the Mitropa Cup boxing matches weren’t even started.

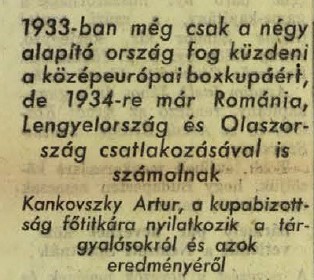

- From Hungarian journal Nemzeti Sport (National sport) announcing for Kozépeuropai Kupa (Central Europa Cup) 1934 the participation of Romania, Poland (Lengyelorszag) and Italy (Olaszorszag).

A parenthesis in the Tournament was represented by the European Championships in Budapest that confirmed the goodness of the boxers belonging to the Mitropa Cup and corroborated its prestige. But, on the other hand, this event highlighted another aspect, more similar than emerged in football and ice hockey, pertinent to the composition of a Central European block that called itself the careful executor of the FIBA rules and challenged, especially from the Hungarian side, the diversity of the application by the British referees.

The crisis of the Mitropa Cup emerged after the dispute of the European tournament that is in October 1934 when, in view of the meeting Czechoslovakia vs. Germany scheduled in Prague, the Viennese referees of Jewish origin Floh and Scholz were designated. The German federation invoked the Aryan paragraph in force in their country (1). At this point, Kankovsky’s position was firm because he could not allow FIBA to indirectly bend to the Nazi diktat. The match took place, Germany won, mathematically conquering the Cup.

- One of strongest boxers Hans Wiltschek, better known as Hans Jaro

The matches Austria vs. Germany remained undisputed, considered as canceled. Czechoslovakia, at this point, seeing future problems, thought it well to declare itself out of any new edition of the Mitropa Cup, due to financial unsustainability. The Austrian federation took the opportunity and in May 1935 announced its renunciation of the event for same reasons.

In November 1935 the Slovak federation, which was a sub-federation of the Czechoslovakian one, announced its intention to establish a competition between the cities of Vienna, Budapest, Bratislava and Zlin, this the heart of Czech-speaking boxing. The title of the event was neutral, relying on the geographical location, the Danube Cup. The proposal was not put into practice, although the town meetings between the representatives in question were held, as were again bilateral meetings between Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The “Danube” solution (to name Danube Cup instead of Mitropa) emerged again in 1939 in football at the time of the end of the International Cup, between Hungary, Yugoslavia and Romania. This symbolic downgrading from Mitropa to Danube will be used in the features of another Central European tournament, that of lawn tennis.

- Born in Graz, Austrian Hans Zehetmayer won the European championships 1934 of Budapest in lightheavyweight. Here mention of photographer Ernst Hilscher

Article © Gherardo Bonini

To read Part 4 please click HERE