Introduction

This research on the history of the Herryville velodrome in Evergem near Ghent (Belgium) was started on the occasion of Evergem Ontrafeld (Evergem Unraveled), a public participation heritage project established in 2021 by local hobby historians and heritage volunteers under the initiative and guidance of the municipal council on heritage and culture. The aim of the project is to collect, examine and unlock local heritage objects on a provincial digital platform while bringing people together around the heritage in their neighborhood. Finally the results and insights are supposed to lead to new initiatives and projects.

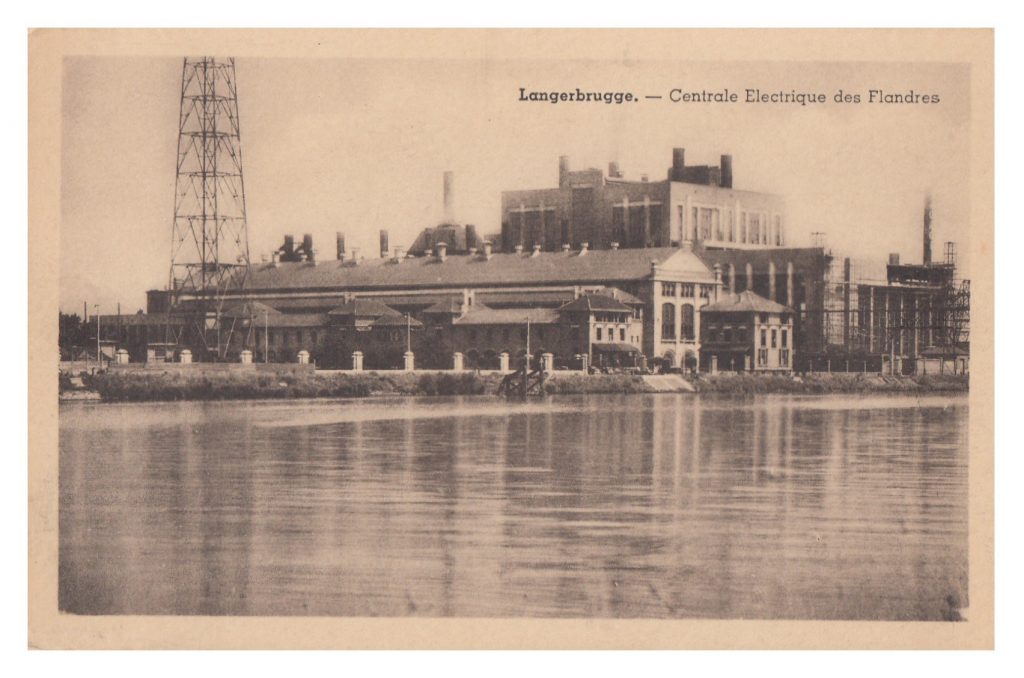

Evergem Ontrafeld started off in the submunicipality of Langerbrugge near the Ghent-Terneuzen Channel where several important industrial and architectural heritage objects were located. The power station of the Centrales Électriques des Flandres et du Brabant (CEFB) and the garden city Herryville with its sports and leisure infrastructure in particular were obviously the (sports) historical sites of our interest.

The history of garden cities

As a result of the second industrial revolution in the nineteenth century there was an accelerated urbanization and an increasing demand for decent housing for the immigrant workmen and their families. Landowners and speculators bought fallow lands in the immediate environment of the factories and erected housing blocks with very tiny fifteen to twenty square meter row houses. Industrials invested in the surrounding land of their companies as well, not only with the prospect of a possible expansion in the future, but also as a lucrative investment in low-cost housing. Besides the profits of the investment, the company directors also had an important means of exerted pressure against rebellious workers who not only could lose their job but later also be kicked out of their house by lack of income.

The miserable living circumstances, unsanitary conditions and subsequent diseases caused a lot of criticism by the city authorities. After the Great War under increasing pressure of the labor movement protective measures related to building legislation were taken by the government, while the first Garden Cities were erected. The garden city movement is defined as ‘a method of urban planning in which self-contained communities are surrounded by “greenbelts”, containing proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture’.[1] These construction projects on the outskirts of the cities were mostly build by social or urban housing companies. In some cases, the client was a company or factory that had a garden city built for the (management) staff, like the Centrales Électriques des Flandres et du Brabant in Langerbrugge near Evergem.

The electricity power station of Langerbrugge at the Ghent-Terneuzen Channel (postcard)

Centrales Électriques des Flandres (Ltd)

On the initiative of baron Floris van Loo in 1911 the limited company Centrales Électriques des Flandres (CEF) was founded. The construction of a power station in Langerbrugge took about two years and became operational in the spring of 1914. After being shut down for more than a year due to the invasion of German troops, a gradual restart followed in 1916, but towards the end of the war the plant suffered another heavy artillery attack. In the 1920s there was a constant increase in the production of the power station under the management of the co-founder and general director Léopold Herry.[2]

Garden city Herryville

To the example of the British garden city movement the power station company constructed the Cité Jardin Herryville in 1927, a garden city with a dozen of two-family houses reserved for the executive staff.[3] Just like the power station, the plans were designed by Eugène Dhuicque, a well-known architect from Brussels who was often called upon shortly after the First World War for the inventory and restoration of damaged historic buildings in the front zone near the Belgian coast.[4] A year later Dhuicque was also asked to construct a sports and leisure infrastructure on the wasteland between the power station and the garden city.

The Herryville velodrome between the garden city and the power station near the channel (1952) [5]

Corporate sports originating from the UK were brought to the continent at the end of the nineteenth century. After the introduction of the eight-hour working day under the influence of the labor movement and the democratization of several sporting disciplines after the First World War, this new form of recreational sports experience was increasingly introduced into the corporate culture in Belgium. Under the heading of ‘well-being at work’ (Industrial Welfare), socially minded business leaders found that sports had a positive influence on the professional performance of their staff.[6] And in addition joint sports stimulated the general group atmosphere on the work floor and created a loyal corporate culture among the employees.

A sports and leisure infrastructure was built on the vacant lot between the power station and the city garden, including tennis courts, a swimming pool, a canteen and a meeting and party room (the Casino). And following the founding of the business-related cycling club VC Herryville, a 366-metre-long concrete velodrome was erected in 1929.[7]

Most resources state that the Herryville garden city, the sports fields and the velodrome were reserved for the executive staff and foremen of the power station. If so, the whole project could be considered as a selective and dubious way of company welfare, because while the works of the velodrome had started during the summer of 1929 and the executives were eagerly awaiting their playground, social unrest grew among the lower staff. The unions received complaints from workers about a deferred wage increase of five percent as a result of the index jump in April and threatened actions.[8] After several meetings with the union, the management of the company gave in and the wage demands of the employees were granted a month later.[9]

The above mentioned arguments show that in this specific case the so-called social objectives with regard to the housing policy and the sports and leisure infrastructure by the management need to be nuanced. After a few incidents at the end of the twenties, among which an explosion and a fire with a prolonged power outage as result, the director Herry was convinced that additional measures were necessary. The power station not only had to be operational on a continuous basis, but in addition to a workforce with a regular work pattern it also needed a stand-by duty. Herryville and its sporting fields were -due to the then isolated location of and the difficult access to the power station- primarily built for engineers and highly trained specialists who manned this stand-by service and could quickly reach the site in the event of major power failures. And although the construction of the velodrome was well approved by the majority of the staff, yet it was heavily criticized by the Management Board and would lead to the premature resignation of director Herry.[10]

A difficult startup

In general most of the velodromes were affiliated to the Belgian cycling federation KBWB (Koninklijke Belgische Wielrijdersbond). In order to protect them there was a regulation that a new velodrome built within a radius of fifteen kilometers around an existing velodrome was not given a permit for organizing sports events. The Zelzate velodrome already had to face the competition of those from across the Dutch border, in Sas-van-Gent and Hulst. The possible increased concurrence as a result of a cycling track in Evergem-Langerbrugge obviously caused great concern. But in an interview with the Flemish leading sports newspaper Sportwereld the president of VC Herryville Maurice Cantineau declared that “… we do not want to bother Zelzate in anything or cause any financial damage” and “… If Zelzate does not object to our affiliation to the cycling federation, we will accept their competition calendar and organize our events on other dates.”[11]

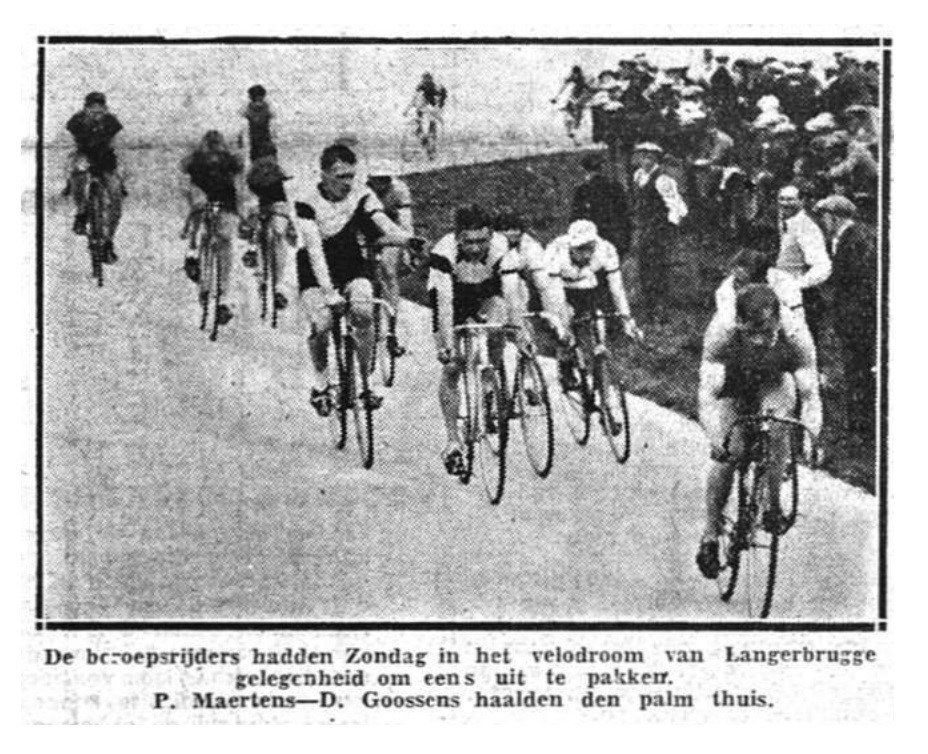

A photo of a cycling event in 1931.[12]

The Langerbrugge track was also the arrival place for several big races for independent professional riders, like the Tour of Flanders in 1932 and the Tour of Belgium in 1932 and 1938.[14]

But the aftermath of the First World War, the economic crisis and the growing popularity of football as a spectator sport had weakened track racing in Belgium significantly. Of the forty-eight velodromes in 1925, only a dozen remained in the late nineteen thirties.[15] Despite the need for approved velodromes in the region, the high expectations as the concrete track was considered one of the best in Europe and the plans to involve Herryville in all kinds of national and international championships, track cycling in Langerbrugge did not really get off the ground.[16] The isolated location, inadequate accommodation and an absent management structure prevented organizers and union members from considering the velodrome as a fully-fledged alternative. The maintenance of the track was virtually non-existent, there were no stands with covered seats for spectators, organizers, employees and commissioners of the cycling association, and there was also a lack of material available to allow the cycling events to take place safely. In addition, already during the construction of the velodrome the management of VC Herryville declared that no profitable goal was being pursued. The entire sports infrastructure was primarily intended as a training facility for the staff of the power station and as far as the velodrome was concerned, annually only four meetings would be planned in collaboration with the Belgian cycling federation.[17] After the appointment of the new director who took over the management of the power station from Leopold Herry in 1933, cycling events in the Langerbrugge were put on the back burner.

The only fatal accident in the Herryville velodrome happened during a cycling event on Sunday July 24, 1932. The race was suddenly marred by a nasty fall on the head by the young promising cyclist Edmond Caus. Despite symptoms of a concussion, the rider had no serious injuries and was taken home. The next day his condition deteriorated and he was taken to the hospital where a severe skull fracture was diagnosed. Caus underwent surgery but passed away to his injuries on Tuesday morning. The 22-year-old young man who had only turned professional the year before, was buried on Friday morning in the presence of the local cycling world and many sympathizers at the Campo Santo cemetery in Ghent.[18]

A newspaper photo of the unfortunate cycling meeting of July 24, 1932.[19]

Also during the Second World War no significant cycling events worth mentioning were organized, as VC Herryville had stopped all club activities. To meet the food shortage during the war years, the workers were allowed to grow vegetables around the power station and on the centre field of the cycling track. After the war the vegetable gardens gradually disappeared, so that from 1949 the football club FC CEFB could play its matches in the velodrome.[20] An appeal for a manager of the Herryville velodrome in an article in the newspaper Het Volk in 1948 confirms the argument that the cycling club no longer existed or that it was no longer able to manage the velodrome and organize cycling events.[21]

When, at the end of the nineteen fifties Oscar Daemers, former cyclist and director of the Ghent velodrome ‘t Kuipke, rediscovered Herryville, track specialists such as Patrick Sercu, Leo Sterckx and Willy Debosscher trained extensively again in preparation for the world championships and the Olympic Games.[22]

And in the early nineteen eighties competitive track cycling in the velodrome experienced a brief revival. From 1981 till 1985, Herryville was the battleground of the Belgian track championships with many well-known pro-cyclists like Michel Vaarten, Dirk Heirweg, Rik Van Slijcke and Stan Tourné.[23]

Due to the preparatory works of the new cycling track on the Blaarmeersen in Ghent (now the Flemish Cycling Center Eddy Merckx) at the end of the eighties, the Langerbrugge velodrome was left to its fate and fell into serious disrepair. The Belgian Department for Landscape Architecture tried to protect the velodrome as an architectural heritage object, but the costs for the restoration would have amounted to millions of Belgian francs. When concrete rot had affected the track to such an extent that it started to pose a danger to playing children and walkers, the track was demolished in 1996.[24]

The remains of the velodrome and the garden city have been protected as a village scene and architectural heritage since 1996 and are now part of the in 2019 opened Langerbrugge South Park.[25]

The remnants of the Herryville velodrome in the Langerbrugge Park.

Conclusion

Despite a small honors list the Herryville velodrome was of significant sports historical importance. The cycling track was an outsider of its kind and, due to its socio-economic approach, unique in Flanders. Unlike the other velodromes that had direct economic motives for generating income, Herryville was built with a completely different objective. The velodrome was primarily intended to serve the interests of the corporate culture of the power station company, and consequently had an indirect economic motive. When VC Herryville disappeared from the scene and the central square was only used to host football matches, the track was left to itself. It ultimately also contributed to the inglorious end of the Langerbrugge-Herryville velodrome.

Article © Filip Walenta (Karelvanwijnendaele.be Project)

Notes

[1] Garden city movement, Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garden_city_movement> (Accessed: October 18, 2021).

[2] De Raedt, Pieter, De elektriciteitscentrale van Langerbrugge, Tijdschrift voor Industriële Cultuur (2013) 30, no. 122, 32-43.

[3] Geschiedenis KVE-Gent, KVE-Gent.

<https://www.kvegent.be/index.php/geschiedenis-kve/13-geschiedenis-kve> (Accessed: October 18, 2021).

[4] Eugène Dhuicque, Inventaris Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed.

<https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten?tekst=dhuicque> (Accessed: October 18, 2021).

[5] Luchtfoto 1952_B3-LOKEREN_186, Cartesius. Maps, plans, sketches and aerial imagery.

<https://cartesius.be> (Accessed: October 18, 2021).

[6] Crewe, Steven Lea, Sport, Recreation and the Workplace in England, c.1918 – c.1970, (Leicester 2014), 11-12.

[7] Geschiedenis KVE-Gent, KVE-Gent.

<https://www.kvegent.be/index.php/geschiedenis-kve/13-geschiedenis-kve> (Accessed: October 18, 2021).

[8] Vooruit, June 21, 1929.

[9] Vooruit, July 14, 1929.

[10] Kerckhaert Noël, De Vleeschauwer Dirk, Het nieuwe licht uit Langerbrugge 1900-1940, (Antwerpen: EBES, 1990), 438-440.

[11] Sportwereld, May 19, 1929.

[12] Kerckhaert Noël, De Vleeschauwer Dirk, Het nieuwe licht uit Langerbrugge 1900-1940, (Antwerpen: EBES, 1990), 443.

[13] Sportwereld, June 15, 1929.

[14] Vooruit, April 30, 1932; Het Volk, June 2, 1932; Het Nieuws van den Dag, June 27, 1938.

[15] Het Nieuws van den Dag, December 28, 1938.

[16] Het Nieuws van den Dag, April 8, 1938; Vooruit, May 8, 1938; Het Volk, February 18, 1948.

[17] Sportwereld, February 28, 1929; ibid, May 19, 1929.

[18] Sportwereld, July 27, 1932; ibid, July 30, 1932.

[19] Vooruit, July 26, 1932.

[20] Geschiedenis KVE-Gent, KVE-Gent.

[21] Het Volk, February 18, 1948.

[22] Geschiedenis KVE-Gent, KVE-Gent.

[23] De Voorpost, April 4, 1982; Nieuwe Gazet van Aalst, June 22, 1984; De Voorpost, May 24, 1985.

[24] Geschiedenis KVE-Gent, KVE-Gent.

[25] Tuinwijk Herryville met velodroom, Inventaris Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed.

<https://id.erfgoed.net/erfgoedobjecten/125501> (Accessed: October 16, 2021).

Other resources

Koninklijke Bibliotheek – Bibliothèque Royal, KBR:Belgicapress.

<https://belgicapress.be> (Accessed: October 10-20, 2021).

Digitaal krantenarchief – Stadsarchief Aalst. <https://aalst.courant.nu/> (Accessed: October 10, 2021).

Respect voor het industrieel erfgoed: de geschiedenis van het ECVB, Gentcement.

<https://www.gentcement.be/2013/09/respect-voor-het-industrieel-erfgoed-de-geschiedenis-van-het-ecvb/> (Accessed: October 18, 2021).

According to my family, Herryville was named after the name of my grand-grand_father, Leopold Herry, who was a director at the Langerbrugge electric factory before the 2nd Word War.