On the 9th October this year (2025) the former Stoke City footballer Frank Soo, was awarded a posthumous ‘honorary cap’ by the FA in recognition of his achievements on the football field, during World War Two.

Soo played nine times for England during the wartime period making him the first player of East South East Asian ( ESEA) origin and the first ‘non white’ player to represent the national team, but the sport’s World Governing Body (FIFA) did not recognise players like Frank Soo because the wartime international matches were deemed to be ‘unofficial’ due to the practicalities of war, including loss and deployment of players, which restricted the FA from selecting players and recognising games in the same way as in peacetime.

Frank Soo: Soo played nine times for England during the war years but like many others, was never awarded a cap

At the outbreak of war in 1939, English professional football was largely suspended, but soon after a modified regional league system called ’The Wartime League’ was established to provide entertainment and boost morale on the home front; inter service and ‘international matches’ were also played by England (29) Scotland (19), Wales (17) and Northern Ireland (7), primarily against each other.

Instead of the usual national divisions, regional leagues were set up in England, with teams from the same general areas competing against each other to minimise travel due to government restrictions and ‘The Football League War Cup’ was also introduced to replace the FA Cup.

Matthew Taylor in ‘The Association Game: A History of British Football’ (2013), believes that,

‘The continuation had a positive impact on society as a whole and it was during the ‘’people’s war’’ that the idea that football had a central role in British social and cultural life first took root.’

The leagues were organised for the purpose of continuation and did not therefore, involve promotion or relegation, so the 1939-1940 season featured eight regional divisions, including two in the south, one in the West Midlands, one in the East Midlands and four in the North and was witnessed by over 600,000 spectators; The 11 London clubs were split into two groups, South A and South B, which caused some dissatisfaction among some of the clubs, who called for a separate London division that they could run themselves under the auspices of the London FA.

As a result, during the summer of 1941, the London clubs rejected the fixtures organised by the Football League and voted to break away to form their own competition called ‘The London War League’, which was formally sanctioned by the FA. Crowd restrictions, wartime mobility and travel difficulties all affected attendances, but for the London clubs, the league was a qualified success; however, for the start of the 1941-1942 season they rejoined ‘The Wartime League’ and were renamed as ‘League South’, for the rest of the war.

Some notable winners of the leagues included, Wolverhampton Wanderers ( Midland League winners 1939-1940), Preston North End ( North Regional League 1940-41) and Crystal Palace ( South Regional League 1940-41).

In Scotland, competitions were suspended and were replaced by a series of leagues and cup competitions as in England, which was dominated by Glasgow Rangers, who won all six ‘Southern league’ titles between 1940 and 1946 and four ‘Southern league ‘ cups.

In Northern Ireland, football was organised through the ‘North Regional League’ which operated between 1940 and 1947 and teams in the new league were generally made up of amateur players and soldiers; Belfast Celtic were the most prominent club winning the league in 1940-41 and the Irish Cup in 1942-43.

Welsh clubs joined the English regional leagues, with Cardiff City, Swansea Town and Wrexham continuing to play in England, as they had done prior to the war; Newport County withdrew from competitions and their place was taken by ‘Lovell’s Athletic’, an amateur team from ‘GF Lovell and Co’ sweet factory, who were highly successful, winning the Football League West title in 1942-43.

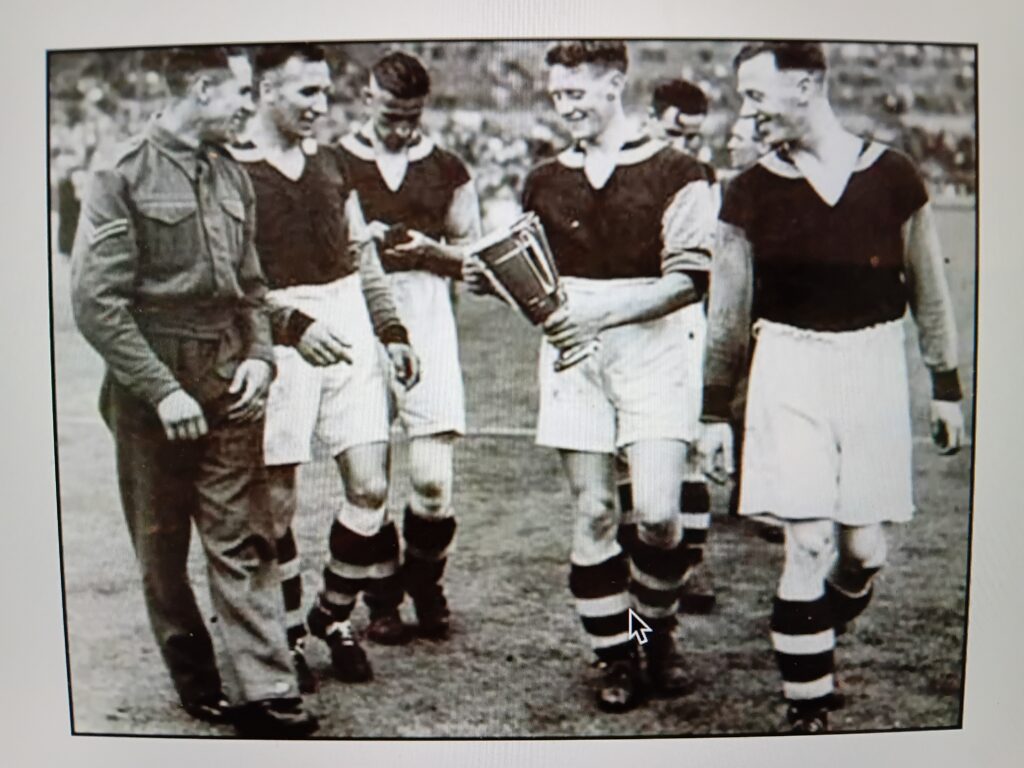

‘The War Cup’ in England took on a different complexion as North and South sections combined for the ten games in the qualifying competition and then the leading 32 teams entered the ‘competition proper’ attracting 72,000 fans for the final at Wembley in June 1940, where West Ham beat Blackburn Rovers 1-0; Reading, Brentford, Arsenal, Aston Villa, Preston Noth End and Charlton Athletic were all winners during the war years.

West Ham players with the War Cup’ in 1940

Source: https://goalchatter.blogspot.com/2014/09/wartime-football-1940-west-hams-cup-win.html

Interestingly, the number of available leather footballs had begun to become a concern as the loss of Singapore to the Japanese in February 1942, severely hit the supply of bladders, due to controls introduced on the manufacturing of rubber, which led manufacturers to develop and use synthetic rubber as a substitute.

While there was no official league, women’s football did take place during the war, despite the decision by the FA in 1921 to ban it from all affiliated grounds and matches were popular, sometimes drawing crowds of up to 50,000; an estimated 150 teams were formed, many from the munitions factories that played games to raise money for the war effort.

The tradition of playing football on Christmas Day, which began in the late 19th century, continued through wartime and in 1940, over 40 matches were played, but when Norwich faced Brighton, the visitors arrived with only five players, so they borrowed volunteers from the crowd – Norwich won 18-0 with striker Fred Chadwick scoring six; several teams also played two games that day, with Leicester losing 5-2 at Northampton in the morning and then Northampton losing 7-2 at Leicester in the afternoon.

As Christmas Day became more family orientated and perhaps more importantly public transport became more limited, most football matches moved to Boxing Day, with the last English League match between Blackpool and Blackburn Rovers played on December 25th 1965 – Rovers winning 4-2.

Image above shows Football in January 1942

Many top players were called up to military service, including established internationals like Stanley Matthews, Willie Thornton, Tom Finney, Ron Jones, Johnny Carey and Billy Wright and in total over 600 professional footballers joined the services, leading to depleted teams that often- fielded ‘guest players’ like Frank Soo ( who was in the RAF and was stationed at various bases around the UK) and despite restrictions, matches often attracted huge crowds with attendance sometimes reaching close to 100,000 for some games, when they were not affected by air raids or sirens; others went into war work and at one time in 1940 for example,18 West Bromwich Albion players worked at a munitions factory in Oldbury.

Image above shows Sir Matt Busby ( centre) in uniform. He was a coach with The Army Physical Training Corps, while also playing for several clubs as a ‘guest’

Inter-service matches were also used to maintain fitness and foster positive relationships between Allied forces, through various competitions like ‘The Inter-Allied Services Cup’, which in 1943 was played between The Army and The RAF at Stamford Bridge; these games provided a vital source of entertainment and a welcome distraction for servicemen and the public alike.

‘Football’ comments Matthew Taylor, ‘was the first British sport to consider seriously how it might be organised and played when peace returned’. However, it would take several years for the sport to resume to its full, pre-war state, with regional competitions being held in the 1945-46 season before the full Football League and a standard FA Cup was restored a year later in England; in both Scotland and Northern Ireland, the official competitive structure resumed in 1946-47.

The ‘British Victory Home Championship’ was played during the 1945-46 season between the four home nations and was won by Scotland with the other nations all finishing as runners up; but as was the case during the war, the so called ‘Victory Internationals’ were not regarded as ‘full internationals’, so no caps were awarded.

Image above shows One of ‘The Victory Internationals’ in 1946. at Hampden Park Glasgow in front of 139, 000 fans. Scotland won 1-0.

England played France at Wembley in May 1945 ( a 2-2 draw) in front of 65,000 fans, a benefit match for war charities, but the first ‘official’ international fixture for the England team was a 7-2 loss away to The Republic of Ireland in September 1946; their first home fixture was a 1-1 draw against Scotland in April 1947; Wales waited until 1946 to play Scotland in Glasgow losing 3-1,but Northern Ireland would wait until 1949 to resume their international fixture list, losing to England in a 1950 FIFA World Cup qualifier 9-2 at Maine Road, Manchester.

By the end of the war, football had provided far more than entertainment as it offered what Matthew Taylor describes as

consistency and comfort in a time of upheaval and a sense of normalcy for the public which became a way for communities to feel unified after six years of war.

Article copyright of Bill Williams

A leather football c 1943

Footballs were in short supply during the war years.