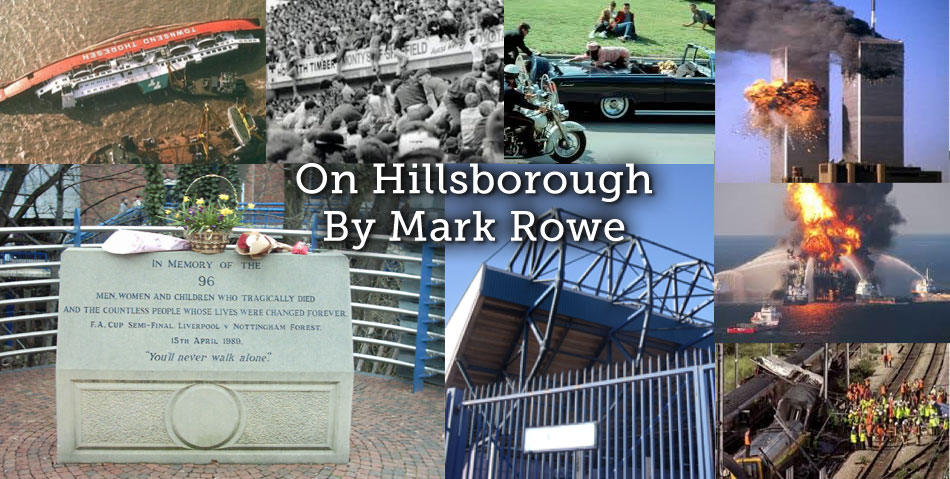

In its way, the Saturday afternoon of April 15, 1989 in a football ground in Sheffield is to English history what a pair of office blocks in New York on September 11, 2001 are to the history of the United States; their most documented times and places so far.

9-11 had its commission; the Hillsborough tragedy, eventually, had its independent panel and a new inquest. The inquest hearings began in April 2014 (and pre-inquest hearings began in April 2013); the jury gave its verdict in April 2016. The statements of hundreds of witnesses, and documents about the Hillsborough ground going back to the 1980s, are online at https://hillsboroughinquests.independent.gov.uk.

- Leppings Lane, Hillsborough 15th April 1989

- Twin Towers, New York 11th September 2001

Like Wikileaks and the Panama Papers, here is a new phenomenon; gigantic amounts of material, stored digitally and, if online, for anyone to read anywhere. The Hillsborough documents are a source for any historian of England of the later 20th century. Just as, depending on age, we can remember what we were doing when we heard of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997, or the assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963, or indeed Hillsborough or 9-11, when we remember that otherwise ordinary day, that becomes a piece of social history.

The documents detail how the police and related public services approached the management not only of sporting events but of leisure crowds in general. Partly driven by Hillsborough and other losses of life, ‘crowd science’ has developed, drawing on physics (the flow of people), architecture (the design of structures) and psychology (how people behave in crowds). We have such a thing as ‘victimology’, the study of being a victim.

Hillsborough offers a case study in crisis management. It can stand as one example in a wider study of workplace failures: alongside Piper Alpha (North Sea oil and gas), the Herald of Free Enterprise (ferries) and Ladbroke Grove (railways). And we can break down that failure into policies (the ways that people did things, that did not meet the challenge of extremes); command and control (it’s easily overlooked that the stadium was well equipped for its time, with CCTV and radio communications); and organisational culture (around such things as individual initiative); and, again, psychology (why did police officers facing the Leppings Lane end act the ways they did?). Hillsborough is – not least according to the laws of the time – a question of health and safety, according to the Health and Safety Act 1974 and the Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975, which raises the question of how Hillsborough fits into a wider, historical story of past crushings and losses of life among crowds; a story of how a society learns (or not) from experience; of how it values life; and how those in power respond to a disaster on their shift. And, while this remains controversial over Hillsborough, we can ask how people behave on sporting and other occasions; whether any people behave differently, whether in a carnivalesque or anti-social way. What is sport, or more generally leisure: a mirror of society, or a respite from it, as recreation? It must be a part of society, because it is made up of people, and health and safety and other laws apply; and yet there is something different, liminal, about moving crowds, whether in stadia or night-clubs or concert halls or open-air music festivals; different from the crowds in metropolitan train stations going to and from work. Sports fans come together with risks, as was played out so painfully on the afternoon of Hillsborough.

- Piper Alfa

- Herald of Free Enterprise

- Ladbroke Grove

And there Hillsborough becomes a more profound source for the historian; as a confirmation of history as a method, whether as the mere study of the past, or of change (or continuity, an absence of change) over time. For while geography mattered at Hillsborough – people died because they were in too confined a space – it was absolutely an historical event. Nobody got up that day wanting to die, or intending that 96 would die (and hundreds be injured). Hillsborough was an ordinary FA Cup semi-final, until a series of events over time led to a turning point; beyond it, procedures, the latest technology, and the experience of police officers, were not good enough to prevent loss of life. As one South Yorkshire Police superintendent put it to his chief constable at a meeting the day after, in a document on the inquest website, ‘the situation deteriorated from 2.30pm and never improved’. As an aside, as those words suggest, Hillsborough can also be a study in how we use language; and it raises questions about truth; of how reality is recorded (according to the website of the Independent Police Complaints Commission, its investigation, begun in 2012, into the police after Hillsborough is ‘the biggest inquiry into alleged police criminality ever in England’). Hillsborough at its most profoundest can make us question the nature of existence. If, as crowd scientists would argue, there came a point at Hillsborough when loss of life was inevitable – because too many people were in too small a space – what does that say about the free will or destiny of anyone?

- Hillsborough