Niall Ferguson’s recent book, The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Power makes a compelling case that social networks have historically been the drivers of political change. It made me think that they should be formally credited with similar influence as regards the origins and early development of football. Certainly, a number of the observations that he makes about the significance of social networks is consistent with what I discovered in my study of the origins of football in Bradford.

What is remarkable about the spread of ‘football’ in Bradford in the late 1870s is the extent to which it embraced a relatively broad cross-section of people from different social groups, albeit in particular from the skilled labour and middle classes of society. The enthusiasm for the game even in its formative years appears to have been infectious but the popularity of football could never have occurred without people becoming aware of it as a recreational option. How do we explain like-minded people having been brought together to play?

The example of how the craze for cycling spread in Bradford from the spring of 1869 demonstrates the latent demand that had existed for new recreational options and the degree to which a section of the population was receptive to new activities. What is notable is how rapidly ‘velocipede mania’ became established in the town having only originated the year before in New York and Paris. Admittedly such mania was a national phenomenon, but it was the viral spread that is impressive, testament to the efficacy of communications long before the internet. According to local newspapers in the summer of 1869, cycling had become relatively commonplace on Manningham Lane, the ‘boulevard’ that led into the centre of the town from the eponymous township to the north. For people to embrace cycling they needed an awareness of it that would have come from two critical factors – firstly, the visibility of the activity and secondly, the spread of information about it. With regards the former, the fact that Manningham Lane was the only flat road out of the town centre somewhat concentrated cycling activity. As regards information about cycling, whilst there were reports in the Bradford Observer newspaper about the new activity it is my contention that social networking and word of mouth had an equally significant role to play as with any other fashionable activity. The same factor must have been relevant with regards to participation in football in the following decade.

- Cycle advert

In the first instance it was a network of public school alumni that was behind the origins of Bradford FC in 1863 as a means of recreational activity. Links with Bradford Cricket Club then encouraged the recruitment of others seeking winter athleticism and I believe that merchants were attracted by the commercial networking opportunities that the club afforded. Thus the game began to derive momentum. The next stage in its development came with football gaining visibility and a key milestone was in 1871 when Bradford FC began playing games at Peel Park, a popular public recreational venue. I believe it was this that provided the sort of exposure that the game had previously lacked as a relatively private indulgence at the ground of Bradford Cricket Club. It seems more than a coincidence that the emergence of a second football club in the town – Bradford Juniors FC – came in the same year that games were first played in Peel Park.

Of course newspapers were important conduits of information and made people aware of sporting events at a national level, in particular the FA Cup Final in 1872, Varsity football fixtures or the inaugural Scotland v England international in 1873. This served to encourage curiosity but that was distinct from providing detail of how to participate. Furthermore, in Bradford where rugby had taken hold the public was unlikely to have comprehended the subtleties of association as opposed to rugby. Newspapers alone could not have made people knowledgeable about ‘football’ although without doubt they helped make ‘football’ mainstream and respectable. Football games were reported in the newspapers in the 1870s in a matter of fact way. The accounts of matches were written by club secretaries who provided them to the press and as such newspaper coverage was entirely factual with an absence of comment about the merits or otherwise of the pastime. If anything, the occasional reports of broken limbs or injuries served to dissuade readers from participation; this meant that it was for people themselves to judge the virtues of the game and my argument is that they derived awareness and a qualitative assessment from social networks. In other words, the spread of information about ‘football’ must have been through word of mouth on a viral basis.

By 1875 there were at least 11 clubs in existence in Bradford and it is possible to talk of a discernible ‘football scene’ in the town that essentially comprised a network of networks. One place in particular can be credited with being the hub – facilitating connections between the various networks – and that was Leuchters’ Restaurant in Bradford, a central venue frequently used for annual meetings and dinners. The restaurant stood adjacent to what was reputedly the world’s largest indoor market and known for its fresh fish and oysters. The venue is better known for having been where the Barbarians rugby club was conceived in April, 1890.

All of the leading Bradford clubs had meetings in Leuchters’ at some stage including Bradford FC and Manningham FC. However, it was not confined to sports clubs and the restaurant was utilised by various other societies for their meetings. The billiards room at the restaurant was reported to have been the haunt of the Bradford FC committee and it operated much like a gentlemens’ club. However, Leuchters’ had a significance beyond a social hub in that it served as a court house, hosted auctions and provided a venue for merchants and professionals to discuss business. Leuchters’ thereby assumed importance in the daily life of Bradford and should be credited with accelerating the development of football by bringing together enthusiasts of the game, particularly among the emergent middle class. Law students and clerks were prominent in the early football clubs and needless to say it was Leuchters’ that hosted meetings of the Bradford Law Students’ Society.

If Leuchters’ was a preserve of merchants, professionals and the middle class, the workplace would have provided the physical connection between young merchants and warehouse managers who became equally prevalent in football teams. Similarly, the workplace likely brought together a community to encourage new players and later, spectators.

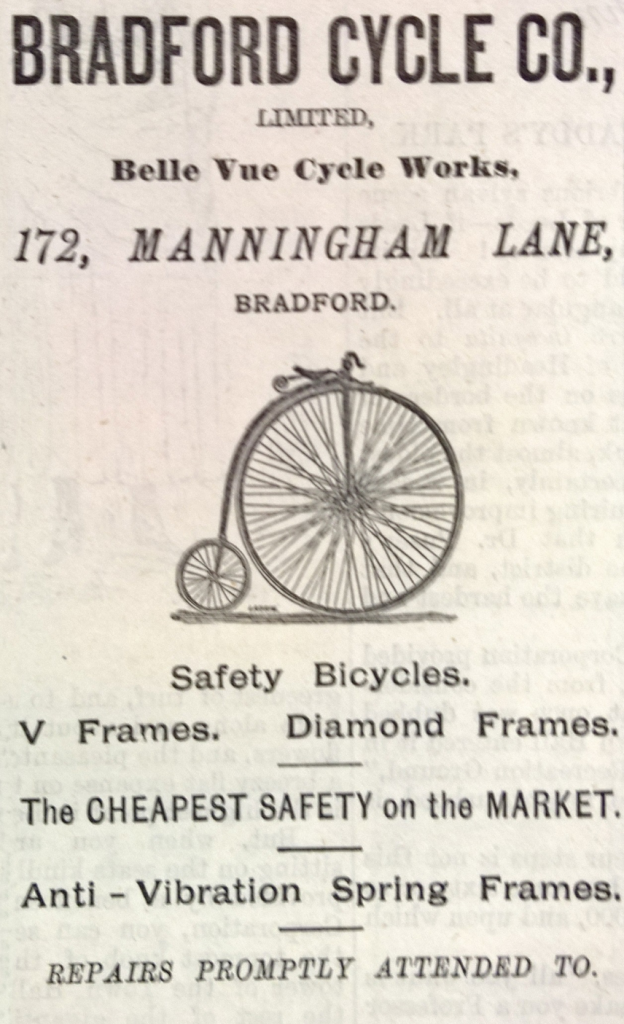

Two organisations in particular helped to encourage interest in football and athleticism in Bradford. By far the most significant was the Volunteer movement which actively promoted physical activity and in 1875 established its own football club with roughly equal representation of officers, NCOs and privates. The other was the Bradford Saturday Half-day Closing Association which existed to lobby for greater leisure time as well as to organise ‘purposeful’ recreational pursuits. People known to be active in the latter were also known to be involved with football, the best example of which was Arthur McWeeney who acted as secretary of the Bradford Saturday Half-day Closing Association, Bradford Caledonians FC and later Manningham FC.

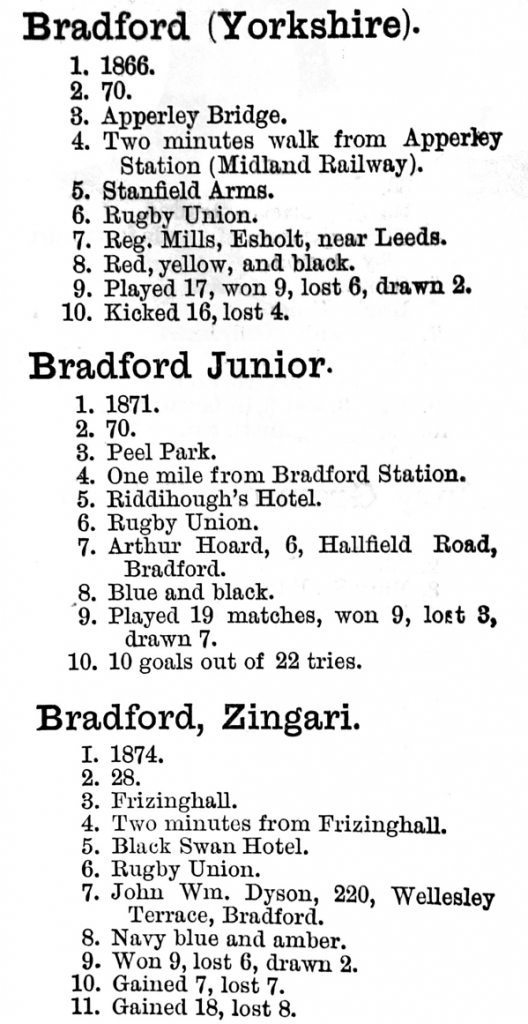

- 1876 Football Annual – Bradford Zingari

The Caledonians club (established in 1873) became the largest in Bradford, as active at football as the Bradford Caledonian Curling Club had been at its sport and as the name suggests, it is no coincidence that it comprised many people with Scottish origins. For good measure, a large proportion of those who played for the Caledonians were also members of the local Rifle Volunteers.

Social networks became significant in a number of ways. By connecting football clubs it was possible to organise fixtures and with it came the emergence of local rivalries. By connecting with existing networks related to athletics, gymnastics or cricket, new groups of sportsmen were also brought together that underpinned mutual support for, and encouragement of, athleticism. In the mid 1880s the popularity of ‘football’ as a spectator activity had a lot to do with it becoming fashionable, embraced as an appendage of so-called ‘masher’ culture in the town – mashers being the sharp dressing youth whose ostentatious behaviour signalled the gains in disposable income of their generation.

- 1876 Football Annual – Bradford clubs

It was also the case that political networks connected into sport, the best illustration of which were the efforts made in 1879 by civic dignitaries to revive the then moribund Bradford Cricket Club and develop a new, dedicated sporting enclosure at Park Avenue. Through until the 1930s, Conservative politicians remained anxious to be associated with the city’s senior sports clubs, considered a strong political endorsement. Yet the one social network that I have not found to have been significant in the emergence of football in Bradford was that of religion.

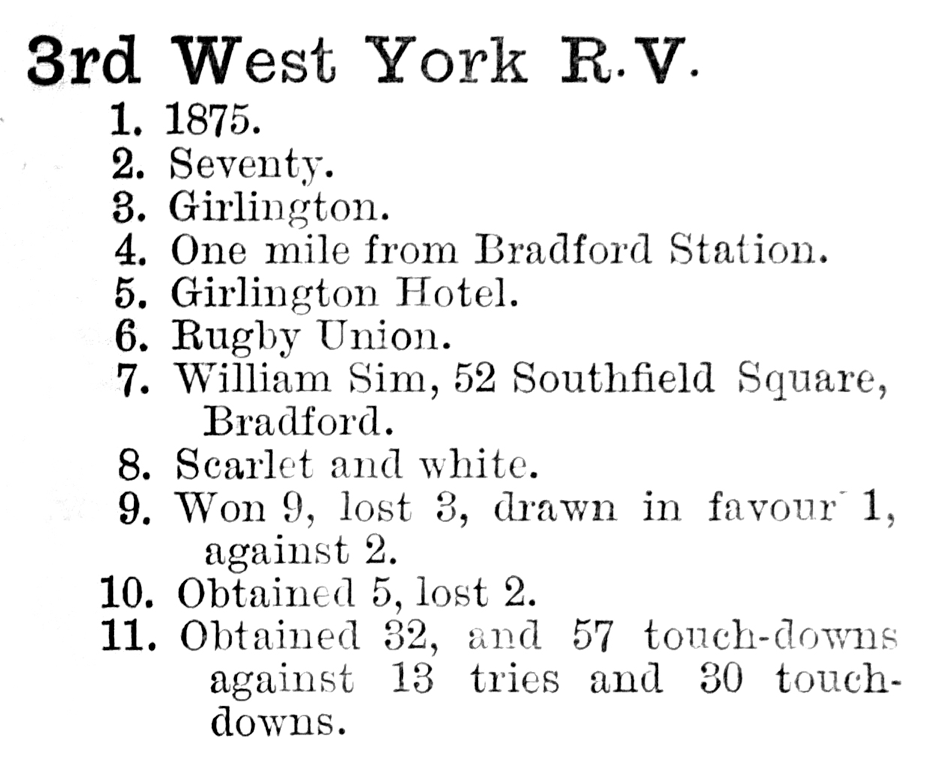

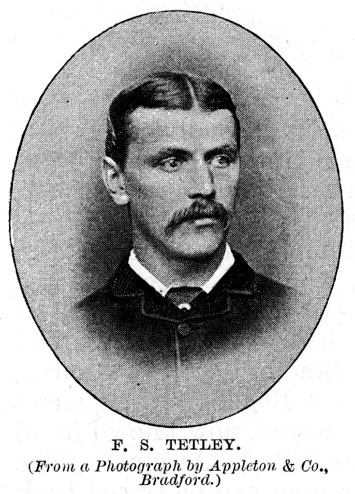

Social networks formed within football also impacted on circles beyond sport. An obvious example of this was commerce and the opportunity that football provided for young merchants to not just generate new connections, but to get to know them and derive comfort about their credit worthiness. A former Bradford FC player in the mid-1870s, Tom Tetley (pictured) later recounted that ‘One of the charms of football was the friendship, the freemasonry, that it created’. Many of his generation later became prominent as leading businessmen and councillors in Bradford. Football created new bonds and the loyalty of former Manningham and Bradford playing members to their old clubs as institutions is striking, notwithstanding the switch of codes in 1895 and at Valley Parade (to soccer) in 1903. (Admittedly less so at Park Avenue when Bradford FC abandoned rugby in 1907.)

Networks were equally relevant within football clubs and integral to their operation. As member organisations, the two leading sides in the town – Bradford FC and Manningham FC – were extremely political organisations with different factions within each, typically linked to player personalities, campaigning for representation on the respective management committees. As I argue in Life at the Top, the lobbying in 1895 of supporter groups based around the public houses managed by current or former players of Bradford FC was an important element of the intrigue that surrounded the debate and subsequent commitment of the club to the creation of the Northern Union and the split in English rugby. Likewise, by the end of the 1890s the leadership of Manningham FC at Valley Parade had become dominated by prominent members of the Primrose League and there was similarly a strong representation of freemasons, a theme that continued within the Bradford City club before World War One and that was significant for fund-raising. Notable is that the Bradford City committee of this era became further connected by marital ties between family members.

The significance of social networks is surely another illustration of why the origins and development of football needs to be examined at a local level. An awareness of the lives of early participants might also promote better understanding of those seminal social networks and their impact. Unfortunately, as Ferguson admitted in his own study, social networks invariably ‘do not leave an orderly paper trail.’

Article © John Dewhirst

John is the author of two books on the origins of sport and development of professional football in Bradford, ROOM AT THE TOP and LIFE AT THE TOP. His blog is at: https://johndewhirst.wordpress.com/