For previous parts to this series, please click on the following links:-

Part 1 – bit.ly/2G1OrmS

Part 2 – bit.ly/2OVewbj

Part 3 – bit.ly/2I57W1x

Part 4 – bit.ly/2G6VGeQ

Part 5 – bit.ly/2IkXinu

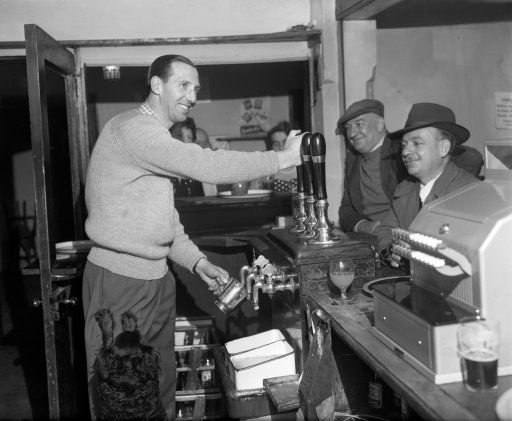

After finally being dismissed as the manager of Notts County, in the autumn of 1958, the quality of Lawton’s life began to deepen in its decline. At first he took a position as manager of the Magna Charta pub in Lowdham village, a few miles east of the city of Nottingham. Lawton stayed there for four years, but after an employee allegedly stole £2,500 from the business, he chose to leave the pub trade, and took up employment as an insurance salesman.

In 1963–1964 Lawton made a brief return to football management with Kettering Town as its caretaker manager, following the resignation of Wally Akers, but at the end of the season the club was relegated from the Southern League Premier Division. And although Tommy was offered the position on a permanent basis, he turned down the invitation preferring to stick with his steady job in the insurance business.

- Tommy Lawton pulling pints behind the bar at the Magna Carta Inn at Lowdham, Nottinghamshire

As was his unfortunate lot, in 1967 he lost his job in insurance, and opened a sporting goods shop in partnership with a friend, with the objective of launching a Tommy Lawton sports goods brand. However, this venture was also doomed to fail and the business was closed down after a couple of months of trading due to lack of sales.

There followed a period during which Lawton received unemployment benefit, before eventually finding work with a Nottingham betting company, and as a salesman for a firm making grandstand seats. His distressing decline from the halcyon days he enjoyed as a star soccer player persisted, and for a couple of years from 1968 to 1970 he made one last attempt to make a go of things as club coach and chief scout at his much loved Notts. County. However, he was sacked once and for all, by the manager Jimmy Sirrel, who chose to appoint his own backroom staff.

During the 1970s the ill-fated Lawton fell on hard times, and had difficulty finding two pennies to rub together. He suffered a heart attack and a bout of thrombosis, became deeper in debt, and returned to unemployment yet again.

As a result of his struggle with debt and its related legal problems media reports graphically illustrated the fall from grace of the once famous sporting celebrity. This led the increasingly desperate Lawton to write an emotional letter to the Chelsea chairman, the celebrated actor Richard Attenborough, asking for a loan of £250, approximately £3,700 today, together with a heartfelt appeal for potential employment.

Dear Dickie, 4 May 1970

Heartfelt congratulations. Truly a great performance and well deserved. Thank you for the tickets we had a wonderful time. Young Tommy has been invited to Leeds, but I will not allow him to leave his studies and school for two years, he’s not making the same mistake as I did. If you want him he is yours and believe me Tommy is going to be very, very good __ with luck. Ability and potential are there.

This is a sad letter for me to write, Dickie, after so many years. Could you let me have a loan of £250 to be repaid in the course of 1 year beginning from the above date. I would not ask, if it wasn’t so urgent and lose your friendship, but all I need is time.

Please, Dickie, please help me. If you cannot see your way to do so, don’t think too badly of me.

Thank you again for the tickets at Wembley and Manchester, and every good wish to Sheila, yourself and family for the future,

God bless,

Yours,

Tommy

The pair had known each other since Lawton’s playing days at Stamford Bridge, and consequently the actor and film director responded with a loan of £100, explaining that loaning him money was somewhat difficult at the time, as his private cash was tied up in a investment company.

Dear Tommy, 12 May, 1970

I really was very distressed to receive your letter since I can well imagine how bad your circumstances must be in order to persuade you that you must write it.

The question of my lending you some money is a very difficult one. You may have read in the press that all my earnings have been taken over by a large company called Constellation Investments, the result is that the private cash available to me is extremely limited and must be for the next five years if the Investment Scheme is to work. I am, however, enclosing a cheque for £ 100.00, which I hope will go towards alleviating your present situation. I will leave the manner of its repayment to you.

I am delighted to hear that you have such high hopes of your son and, needless to say, I am sure he would be immensely welcome at Stamford Bridge, bearing in mind his father’s past connections ! When the time comes perhaps you would let me know and I could arrange a trial for him.

Yes, it was at that we finally won it wasn’t it. Rather more by courage than craft I fear but, nevertheless, at last, after all these years, the Cup is at Stamford Bridge.

Take care of yourself. Do let me know what you are doing.

Kindest regards,

Yours,

Richard Attenborough.

Lawton replied thanking him profusely, declaring that

‘the most important thing to my wife and I is that our friendship is not impaired’.

A short while later, Lawton wrote to Attenborough yet again, informing him he was looking for another job, and asked him if he would be prepared to put in a good word with the pop-singer Adam Faith, who was opening a furnishing company.

Fearing unemployment again, Lawton wrote,

‘Things are pretty tough, Dickie, and what would I have done without you, God alone knows. I have had a series of misfortunes over the years, and now it looks as though this job is in jeopardy’.

He wanted to try to keep his wife and his son happy, and continued by saying his wife was

‘ill with worry of what will come of it all, and I must admit, so am I.’

Attenborough decided to help his hapless friend, and on the 4 June wrote Faith a letter recommending Lawton. However, Faith’s company was based in Scotland, and as the luckless Tommy was based in Nottingham was forced to look elsewhere.

Dear Adam, 4 June,1970

I don’t know whether you will remember him, but the greatest centre-forward that I have ever seen playing for England was a man called Tommy Lawton. He in fact played for Chelsea for a number of years, where I came to know him, and has remained a friend of mine ever since.

I received a letter from him this morning asking if I could possibly put him in touch with you since he had read you were opening a Contract Furnishing Company. This is the business in which he is at present involved and he wondered if there might, by any chance, be an opportunity for him with you. He, at the moment, lives in Nottingham and his address is 55 Patterdale Road, Woodthorpe, Nottingham. I will not, in fact, give him your address since you may not wish to be involved. If, however, you feel there is anything of interest, as far as you are concerned, I would be most grateful if you would drop him a line.

Kindest regards,

Yours,

Richard Attenborough

As anticipated his fears of unemployment inevitably came true, and he asked Attenborough if the Chelsea manager, Dave Sexton, had an opening for a part-time scout. But since, for a period of eight months, no further letters are said to have been exchanged between the pair, it suggests Lawton was not offered a scouting job with the ‘Blues’.

However, in a letter to Attenborough in April 1971, Lawton wrote, ‘I am happy to tell you that I am now in a job that will bring success for the future’. The job was with a large furnishing company based in Tottenham Court Road, London, which employed him as a director of a newly created subsidiary company which bore the name, Tommy Lawton Ltd, at an annual salary of £2,000.00, with a company car, and commission. In the same letter, Tommy asked Attenborough for two tickets for the 1971 FA Cup final, as it was his intention to take his boss. Attenborough agreed to Tommy’s request and sent him the tickets, and Lawton and his boss watched Arsenal beat Liverpool 2-1 in the final at Wembley. Temporarily Tommy seemed to have got his life back on track. However, his happiness was to be brief, very brief.

Lawton’s life was spiralling out of control, and the long-term relationship he had enjoyed with the dependable Attenborough turned sour after he failed to repay the £10 he owed for the two FA Cup tickets Attenborough had provided. Attenborough’s secretary wrote to Lawton in May, and again in July, reminding him that payment for the tickets had not yet been received. And in August Richard Attenborough wrote,

‘I was distressed to learn from my Secretary that she had had no reply to a letter which she apparently wrote to you at the beginning of July. I understand that the two tickets that I obtained for you for the Cup Final have still not been paid for. Had you asked for them from me as a present, I would, as previously, have been delighted to give them to you. However, my office understood that they were to be paid for by your firm and consequently, they were to be the most expensive. I am not a little hurt that you should have caused me this embarrassment.

Misfortune continued to beleaguer the careworn ex-footballer when the large furnishing company that had employed him as a director, went into liquidation. With cumulative debts totalling around £ 2,500 almost half of which were judgments made against him in court, Lawton was once again facing financial crisis. In a foolish attempt to pay off his loans, Lawton irresponsibly continued to write cheques in the company’s name, and in June 1972 appeared in court, charged with obtaining goods and money by deception. When summarising the prosecutor maintained the offences were

‘the culmination of a bad chapter in the life of a professional footballer that had once been notable for glamour and excitement’.

Tommy pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to three years probation, and ordered to pay £240 compensation and £100 in costs. And to make matters worse he was then ordered to pay £304.50 at £1.00 a week, exacerbating his financial state of affairs even more.

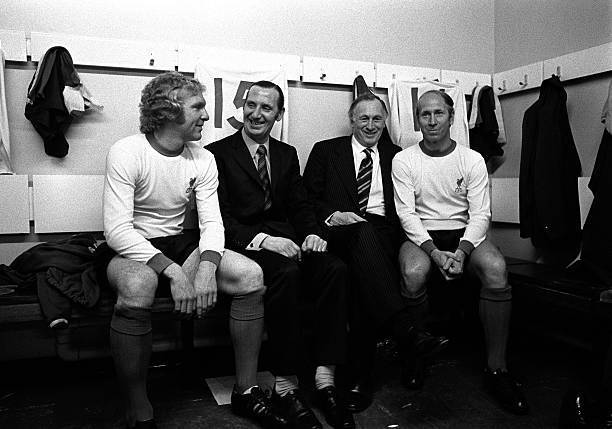

Tommy Lawton was at a really low point in his life. Unemployed, on social security benefit, and heavily in debt, in a desperate attempt to make ends meet, he even sold his football shirts and medals. Fortunately, a close friend and former team-mate, Joe Mercer, was concerned enough to try and help Tommy go some way to solving his financial problems. Mercer arranged a testimonial match for Lawton, and although Notts. County offered Meadow Lane as a venue for the match, it was decided it would be held at Goodison Park, the home of the pair’s former club Everton. The testimonial attracted thousands of fans to watch the game which Everton drew 2-2 against a Great Britain XI, featuring Bobby Moore, Bobby Charlton and Peter Shilton. The great George Best was also expected to play, but he withdrew at the last minute, although he did donate £100 as a gesture to make up for his absence.

- Bobby Moore and Bobby Charlton with Tommy at his Testimonial Game at Goodison Park

Ahead of the testimonial match in November 1972, Tommy Lawton held a frank interview with journalist Michael Carey, of the Guardian.

‘Despair – that was the only word for it. I was out of work and I had no money to speak of. I used to go out in the morning and catch the bus to make my family and the neighbours think I was going to work. Then I would come home in the afternoon and discuss the sort of day I’d had, just like any other working man. The only difference was that I used to sit in the market square or the library until it was time to go home.

At night, I would lie awake and wonder what would happen. I was desperate and there seemed no answer. More than once it crossed my mind to walk into the Trent and end it all, but I always thought about my wife and children and the stigma they would have to bear.

I have had two lives, if you like, one in football and one outside. I never made much money in either of them and I was always a soft touch. In fact, some of my so-called friends from the old days have already been on the telephone again after reading about the testimonial, but I learned my lesson.

He continued by revealing his regret at leaving Kettering for Notts. County, and is so doing planting the seed which led to his eventual downfall.

‘I should have stayed there for three or four years learning my trade. At Arsenal, Tom Whittaker and Bob Wall gave me some tips and tried to help me, but I was too ambitious too soon. I thought I could do as a manager what I did as a player. In this game, you only find out you are wrong when it is too late. Looking back, I realise I might have had a career as a manager if I had not rushed it. On the other hand, I might still have been a big flop, you can never tell. But it was a big mistake to go back to Notts County. There was unrest at the club with a divided board. Half of them hated me and I detested them and I mistakenly thought I could overcome them’.

And yet even after he lost his job as chief scout at Notts. County, he remained complacent, believing he could get find work anywhere because he was Tommy Lawton.

‘I think I could have got another job then, but I sat back expecting people to come to me. I was still conscious of my image, that I was Tommy Lawton, that something would turn up. It was the old story, my pride was shattered, and I did not appreciate that no individual is bigger than the game itself’.

In spite of the money raised through his testimonial match, his financial despair remained bleak, and in August 1974, he was again found guilty of obtaining goods by deception. This time for deceiving a publican friend, by claiming he borrowed £10 for petrol and expenses in order to visit Joe Mercer in Coventry to collect money from the benefit fund. Lawton maintained his car broke down, and by the time he got it going again, it was too late to get there, and so he went back home, and used the money to buy food instead. He couldn’t afford to repay his friend, and as a result was sentenced to 200 hours of Community Service and ordered to pay £40.00 costs.

Money problems arose again in December 1974, when he twice narrowly dodged a prison sentence after being sued by the council for failing to pay his rates arrears. On one occasion an Arsenal supporters club stepped in to pay the bill for him, and later an anonymous friend and former co-worker felt pity for him after such a long run of bad luck, and was sufficiently compassionate enough to bail Tommy out of a prison sentence.

‘You just have to help a man like Tommy, who has been left high and dry by an unkind world’.

Lawton’s monetary misery continued for a further ten years, and it fell to his pals at Brentford Town to organise another testimonial match for him. It also ended in a 2-2 draw, just like his previous testimonial match at Everton. However, on this occasion after the testimonial match, his luck took a turn for the better when, in 1984 as Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government went to war with the National Coal Board against the National Union of Mineworkers in the miner’ strike led by Arthur Scargill, the Nottingham Evening Post offered him a job as a football columnist. He readily accepted and subsequently became respected and admired by its readers.

Tommy Lawton suffered for more than fifteen years of pain and anguish caused by a series of dreadful decisions and a run of bad luck, before eventually his situation, and his life, appreciably improved.

Article © Roy Case

For the final part of this series see – bit.ly/2DCYTRI