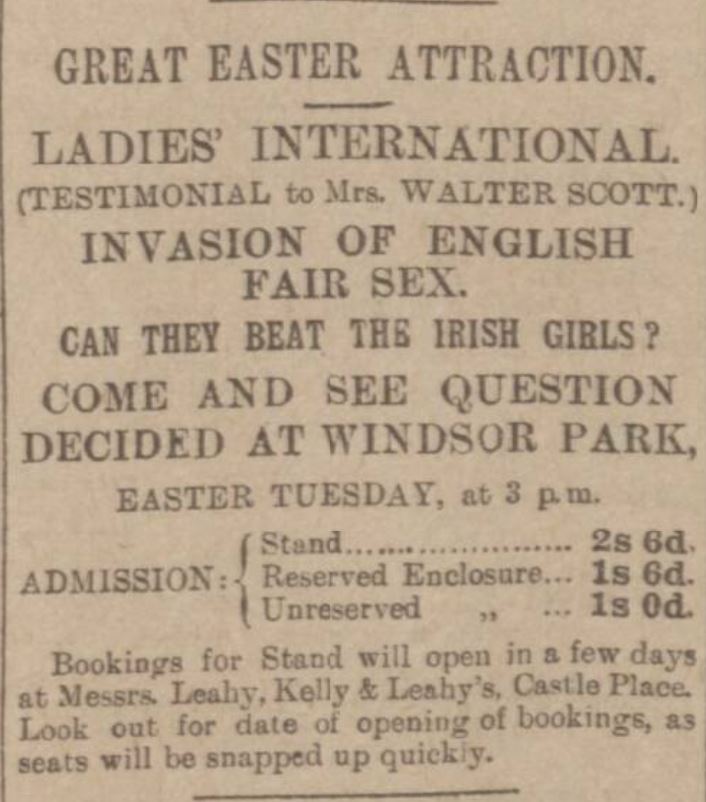

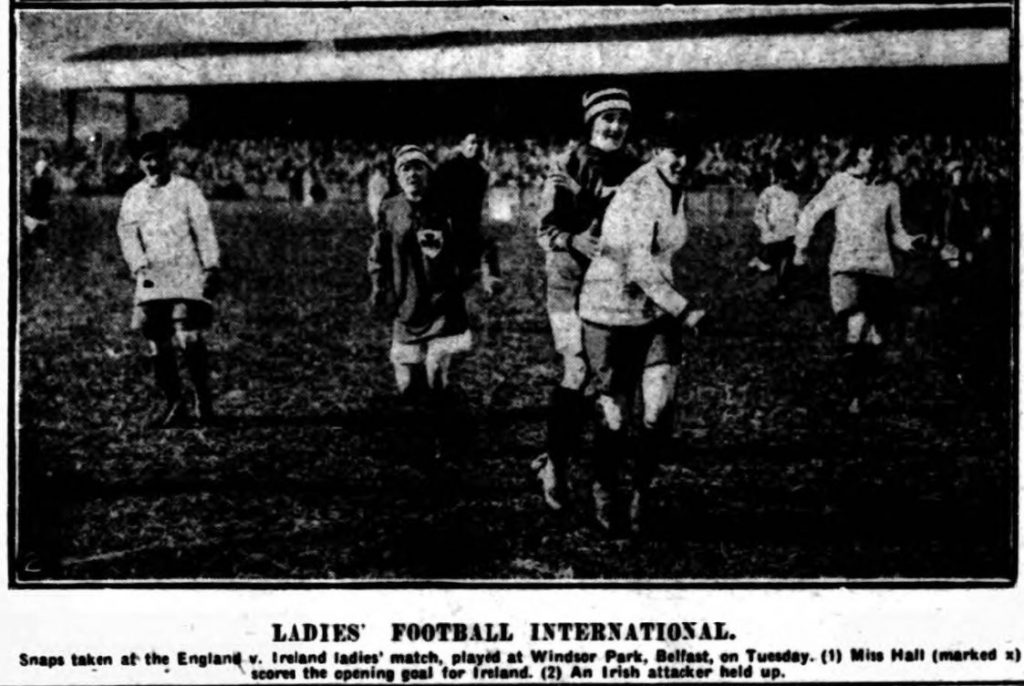

On 29 March 1921, Mrs Walter Scott became one of the first female football administrators to be honoured with a testimonial game. Despite ‘depressing weather’, some 10,000 spectators filled Windsor Park in Belfast to watch a women’s international between Ireland and England.

Northern Whig, 14 March 1921

With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

It had been only four years earlier that she had organised her first women’s game, helping to raise funds for charities during the First World War. But in the intervening years she had become a leading figure, credited as the ‘pioneer of ladies football in Ireland.’ Now, her efforts in promoting women’s games on behalf of wartime and post-war charities was being recognised in spectacular fashion. That so many spectators turned out in bad weather says a great deal, not only about the popularity of women’s football, but of the regard in which Mrs Walter Scott was held.

Belfast Telegraph, 31 March 1921

With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk), Independent News and Media PLC

Who was Mrs Walter Scott? Whereas we know a great deal about male administrators and organisers in the early years of the men’s game, we still know little about their female counterparts in the women’s game. To modern eyes it is noticeable that in all the contemporary newspaper reports, even in the advert for her testimonial game, Mrs Walter Scott’s first name was never used. This, now outdated mode of address, illustrates the image of women at that time as wives first, and people second. Nor have I been able to find image of her so far.[1]

As part of the National Football Museum’s 50:50 strategy and our current Lilly Parr Project (Funded by the AIM Biffa Award History Makers) this two-part article will explore the story of this forgotten figure.[2] In the summer of 2021 we will be opening a new gallery dedicated to the life and legacy of Lilly Parr, a leading player in the famous Dick, Kerr Ladies. As part of this work, we have been researching and exploring the lives of those involved in women’s football before and after the FA’s 1921 ban. It is an early sketch of Mrs Scott, drawn principally from digitised resources. As will be seen, there is much more to research and understand about her and the history of the women’s game, particularly in connection with the First World War, Irish and British history.

What was her first name? It is believed that her maiden name was Diana McDonald.[3] By cross-referencing small clues in newspaper reports with the 1911 Census, she and her husband can be found living at 21 Lothair Avenue, Duncairn, Aintrim. She was 25 when the census was taken and had been born in Co. Fermanagh, while he was 24 and from Belfast. Their marriage certificate reveals that they married in Belfast on 15 April 1910 and that her father was a publican while the 1911 Census describes Walter’s father as a buyer for a wholesale warehouse. Walter worked as a ship building clerk and both he and Diana were Presbyterians. Walter came from a sporting family. He was the youngest of three brothers, all of whom were active in the football community. James played for Cliftonville, one of Belfast’s major clubs, while Herbert was at one time the secretary of Ulster Rangers.[4]

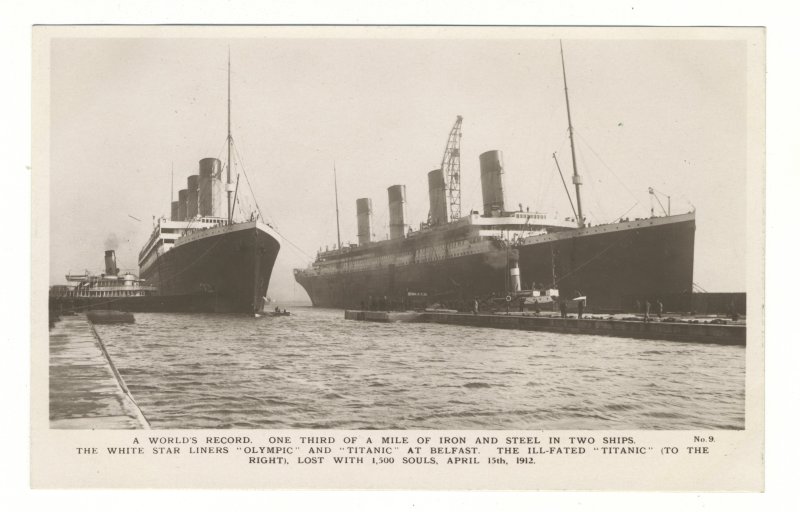

In 1911 they lived within a few miles of the vast shipyards of Harland and Wolff. Two years earlier, work had started on two great ocean liners, RMS Olympic, and her more famous and ill-fated sister, RMS Titanic. A few months after the census was taken, Titanic was officially launched, with over 100,000 people in attendance. Over 15,000 men had worked on her construction and it is possible that Walter may have been one of them.[5]

BELUM.W2011.1295.29, The White Star Liners “Olympic” and “Titanic” Postcard, Walton

© National Museums NI, Collection Ulster Museum

The years after the launch of Titanic saw growing tensions in Ireland over the issue of Home Rule. Irish Nationalists, who were predominantly Catholic, campaigned for greater autonomy from mainland British rule. In contrast, Unionists, who were predominantly Protestant and concentrated in Ulster, campaigned to maintain the status quo. Belfast became the focal point of loyalist Unionism.

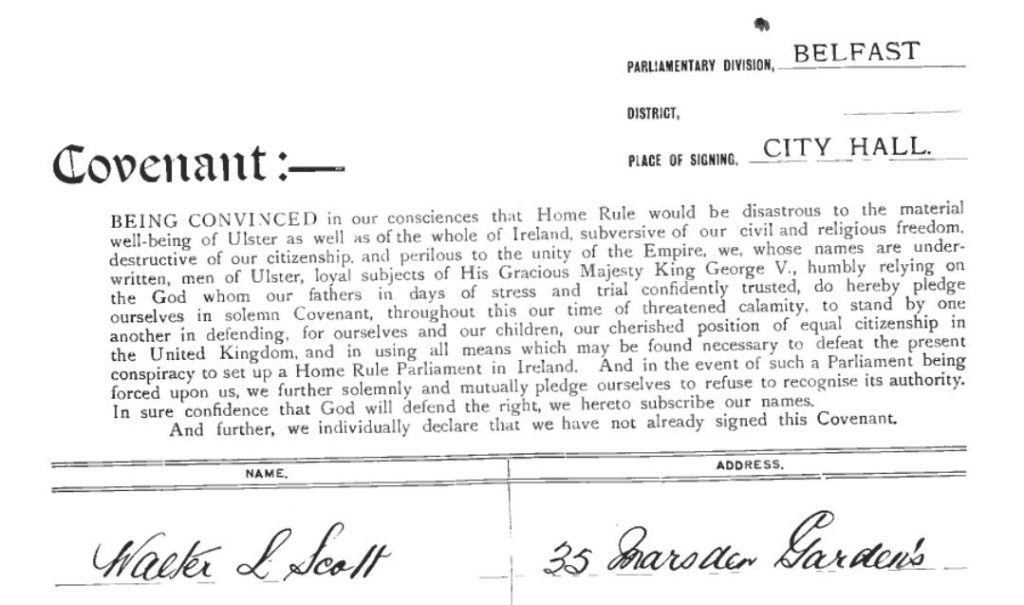

In September 1912, the Ulster Covenant was created. It was signed by over 470,000 men and women who signalled their loyalty to the United Kingdom and their determination to resist the creation of an independent Irish Parliament.[6] One of those men was Walter Scott.

Walter Scott’s signature in the Ulster Covenant

Courtesy of the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

But what of Diana? The historian Daryl Leesworthy searched through the database with me and found no record of her signing the Covenant. By now the couple were living at 35 Marsden Gardens in North Belfast and forty-one one of their neighbours signed, sixteen being women. We do not know why she did not sign but Daryl observed that Diana’s father is also absent from the list, perhaps indicating that her family did not support it. On this central issue Diana differed from her husband and much of her community, and her decision is revealing of the independent choices that women actively made in their public lives.

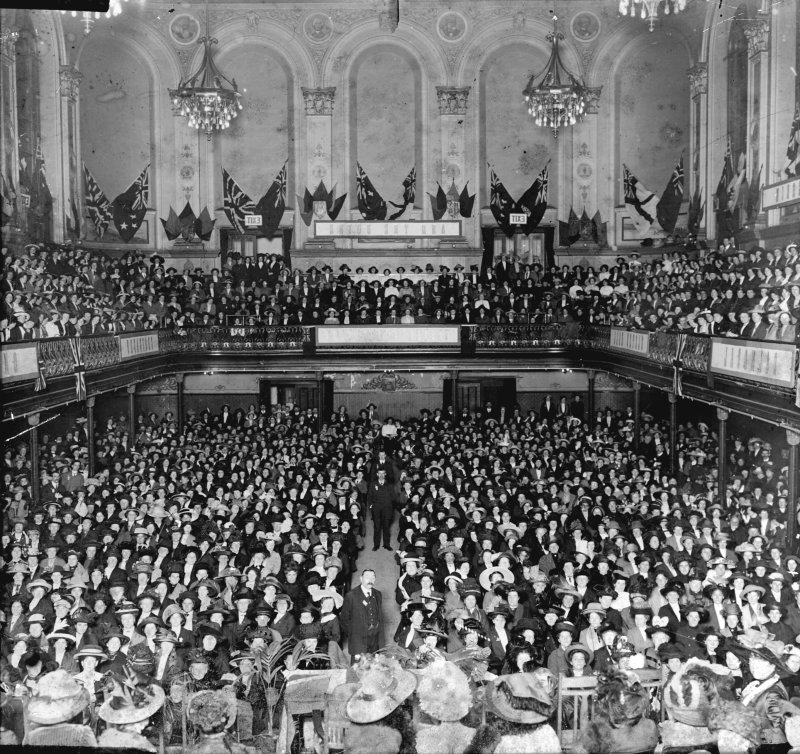

Not signing the Ulster Covenant suggests that Diana was probably not a member of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council. Formed in 1911, within a year it had between 115,000 to 120,000 members, making it the largest female political organisation ever seen in Ireland at that point. They acted as unpaid auxiliary labour, participating in fundraising, petitioning, and canvassing for Unionist politicians.

BELUM.Y11664, Ulster Women’s Unionist Council Demonstration at the Ulster Hall

18th January 1912, A.R. Hogg

© National Museums NI, Collection Ulster Museum

In 1913 the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was formed. In the event of Home Rule being passed, it was to be mobilised to obstruct any attempts to impose it. By 1914, some 100,000 men were estimated to have joined the UVF, many of whom had signed the Ulster Covenant. At present, I have not been able to find out whether Walter was a member of the UVF. At the start of 1914, it was feared that civil war would break out and it was only the outbreak of the First World War that prevented it. Unionists embraced the British cause, with members of the UVF encouraged to volunteer for the British army. An entire division, the 36th (Ulster) was formed out of UVF units and served on the Western Front, most famously at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 .[7] During the war, the UWUC’s focus switched to charity work. The Ulster Women’s Gift Fund was created to support servicemen. Over £100,000 was raised by 1918 through a variety of means and events.[8]

While many men volunteered for the armed forces, many more did not. Walter was one of those who did not join up and in October 1915 he became the secretary of Distillery FC, one of Belfast’s leading professional clubs. Formed in 1880, it was a founder member of the Irish League and the Irish Football Association. One of its most famous ex-players was the defender William McCracken, who was notorious for perfecting the off-side trap in the 1900s with Newcastle United. Football continued in Ireland during the war and while the Irish League was suspended between 1914 and 1919, Distillery played in the Belfast & District League. In June 1918 Walter resigned his post, owing to a ‘new business appointment’, but in August he returned to football, becoming the secretary of Glentoran, another leading Belfast club.[9]

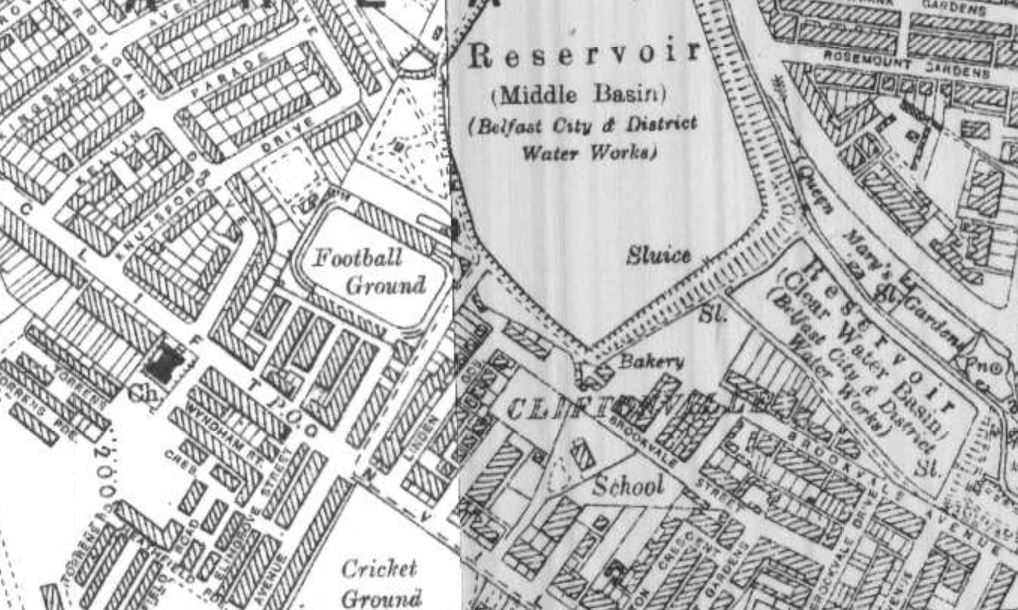

By 1912 the Scott’s lived at Marsden Gardens. Close by was Solitude, the ground of Cliftonville FC

Courtesy of the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

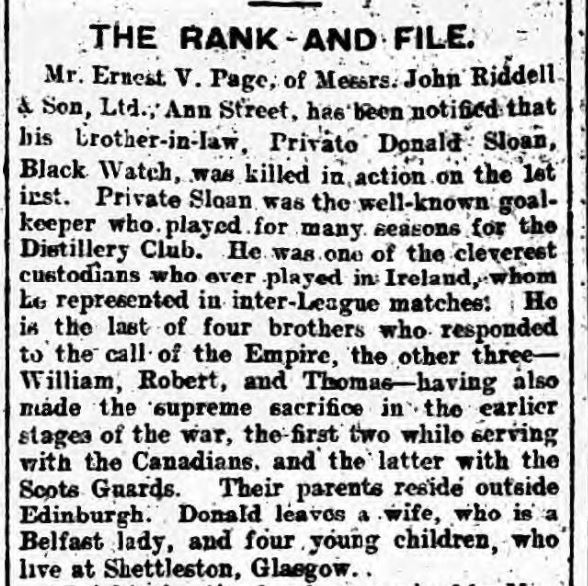

https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/services/search-proni-historical-maps-viewer

Although Walter did not serve in the army, he and Diana would have been keenly aware of the impact of the war on the communities they belonged to. Newspaper reports carried the news of the death of several former Distillery players or club members, like Rifleman David Drennan, killed in a gas attack on 1 September 1916 and who left behind a wife and four children.[10] Also killed was Private Donald Sloan, a former goalkeeper with Distillery, Everton, and Liverpool. His widow lost one of her four children three months later, whereafter she returned to her native Belfast.[11] Another widow was Minnie Hayes. Her husband, First-Class Stoker Joseph C. Hayes, drowned after his submarine sank during the ‘Battle’ of May Island, the name given to a series of disastrous naval accidents in 1918.[12]

Northern Whig, 26 January 1917

With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

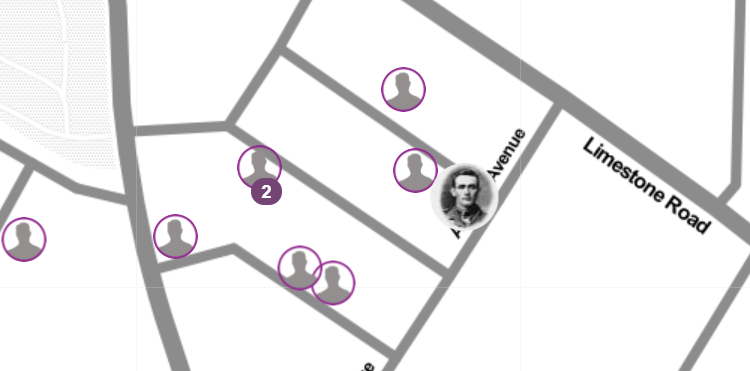

Walter and Diana would also have been aware of losses in the streets around them. The website A Street Near You reveals the loss of life amongst their neighbours at their addresses in 1911 and 1914. At Lothair Avenue there were three deaths. The widowed Thomasina Harper lost a son, Company Quarter-Master Sergeant Frank Harper in October 1916. A month later, Robert and Elizabeth Tennant lost a son, Lieutenant Thomas Tennant. A year later, Robert and Annie Vogan lost their 17-year-old son, Samuel Vogan, who had been a Mess Room Steward in the Merchant Marine.

Lothair Avenue is the first street parallel to Limestone Road

The photograph is of Lieutenant Thomas Tennant, killed in 1916

Courtesy of A Street Near You

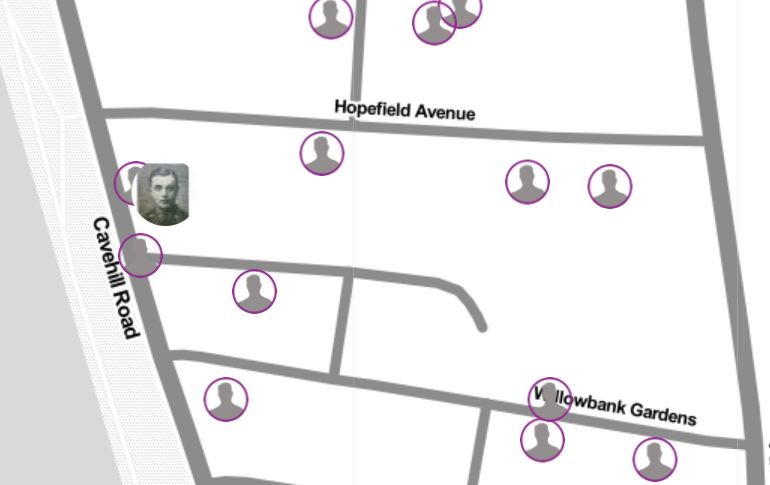

At Marsden Gardens, 2nd Lt. Joseph Cunningham was wounded in 1916. In the same year, Mrs Annie Nelson, lost her son, Private David Nelson at the Somme.[13]

Marsden Gardens is the road in the centre of the map, parallel to Hopfield Avenue

Courtesy of A Street Near You

It is possible that one way in which the Scott’s identified with the wartime efforts of the Protestant Irish community was by naming their house at Marsden Gardens ‘Thiepval.’[14] This reference appears as part of their address in a newspaper in 1918. This was the name of the area where the 36th (Ulster) Division had attacked on the 1 July, the first day of the Battle of the Somme. This was also the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne (1690) and the focus of celebrations and events in Unionist communities.

Another way they engaged was through their support for wartime charities. Like many other women, Diana became heavily involved in organising and supporting such efforts. Some joined or worked for pre-existing organisations, but some also set up their own charities. Diana was credited with inaugurating the Ladies Football Guild during the 1916/17 season.[15] In May 1918, she was described as a:

Strenuous worker in the cause of war charities. She forwards a parcel of good things fortnightly to all the sporting boys of Belfast in the trenches, and collects the wherewith at matches in all kinds of weather.[16]

It seems possible that each club had its own section of the Guild. In February 1918, the Linfield Ladies Football Guild entertained a large group of wounded soldiers at the Ye Olde Castle Restaurant. The report of the event also noted that each week they met in rooms provided free by Linfield, in which they prepared, ‘comforts for the soldiers and sailors.’[17] By 1918, the Ladies Football Guild made a regular monthly 10s subscription to the Ulster Women’s Gift Fund.[18]

Another source of income for the Ladies Football Guild would have been special events. In May 1917, a game was held between the Scottish Command Depot and a reinforced Distillery side. The Scottish team were composed of players with links to leading Scottish clubs, while one of the linesmen was Private Henry Robson, a recipient of the Victoria Cross medal, Britain’s highest award for military gallantry.[19] In the following years though, Diana would become involved in organising a variety of women’s football matches that would mark her out as one of the leading female administrators and organisers in the early history of the women’s game.

Read Part 2 HERE

Article © of Alex Jackson

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Steve Bolton, Dr. Daryl Leesworthy, Dr. David Thoms and Nick Jones for their assistance in the research and writing of this article.

References

[1] I would be most interested to hear from anyone with an image of her or with further information about her and her husband.

[2] https://www.nationalfootballmuseum.com/news/unveiling-new-womens-football-strategy/.

[3] Several reports give their address as 35 Marsden Gardens, Belfast. She is also referred to as Mrs. Walter L. Scott. Their marriage certificate reveals that Walter’s middle name was Leonard. Searching the census for a married Walter L. Scott, living in Belfast, brings up only one result. Marriage certificate obtained from the Irish Civil Records Online Database. My thanks to Daryl Leesworthy for finding it.

[4]Belfast Telegraph, 4 January 1944.

[5] https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zhnkjhv/articles/zfcdqhv

[6] John Hughes Wilson, A History of the First World War in 100 Objects (London: Cassell Illustrated, 2014), p.17.

[7] It should be noted that Irish Nationalists also volunteered in large numbers. John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party urged his supporters to support the British Government.

[8] https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/ulster-women-unionist-council-papers-d1098.pdf

[9] Sport (Dublin), 8 June 1918 and Northern Whig, 17 August 1918.

[10] Belfast Telegraph, 14 September 1916.

[11] Belfast News-Letter, 29 January 1917. Three of Donald’s brothers were also killed in the war. Information on the Sloan family from http://www.ayrshirehistory.org.uk/pdfs/Sanny%20Sloan%20the%20Miners’%20MP.pdf You can see Donald play for the Irish League in the following film clip. https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-england-v-ireland-at-manchester-1905-1905-online

[12] Belfast Telegraph, 12 February 1918. His CWGC record reveals that he served on Submarine K4. For the Battle of May Island see https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/the-battle-of-may-island/?utm_source=November+2019&utm_campaign=f99a29f6b1-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_04_23_11_47_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_05fb12fd3f-f99a29f6b1-232394473

[13] Ballymena Telegraph and Weekly Telegraph, 19 August 1916. https://astreetnearyou.org/#=undefined&lat=10&lon=0&zoom=2 accessed 27.12.2020.

[14] Belfast News-Letter, 24 May 1918. It is given as part of the address.

[15] Belfast News-Letter, 7 September 1917.

[16] Sport (Dublin), 9 February 1918.

[17] Northern Whig, 12 February 1918.

[18] Belfast News-Letter, 2 October 1918.

[19] Belfast News-Letter, 19 May 1917.