Irene Harand (1900-1975) was a woman moved by Christian ideals who established a bond of friendship with the Jewish community, a victim of Nazi persecutions since 1933. She founded a Movement against the inequalities of anti-Semitism, racism, and poverty, which rapidly became known as the Harand Bewegung (Harand Movement). Before its forced closure in 1938 following the Anschluss it had generated 30,000 adherents in Austria, and a few thousand in other countries, even outside Europe. In 1935, she published Sein Kampf (His Fight) against Hitler’s Mein Kampf (My Fight) in which she criticized the lying and delusional theses of Nazism. From 1933, she edited the weekly Gerechtigkeit (Justice) and undertook a strong, continuous, and passionate battle for friendship between Christians and Jews, and the rejection of anti-Semitism. Her guiding principle was that anyone who was a Christian must be against anti-Semitism because this ashamed Christianity. Through rallies, congresses, and conferences, Harand gave life and concreteness to this ideal.

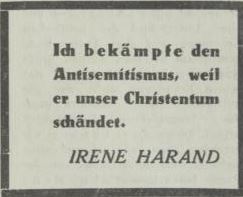

This is the motto issued in the copies of Gerechtigkeit

Anti-semitism is a shame for Christendom

Before the forced closure in 1938, when there was already a bounty announced by Hitler of 100,000 marks on her head, Harand countered the Nazi propaganda blow for blow, openly denouncing all aspects of its aggressive and coercive policy. Through the pages of Gerechtigkeit, she highlighted the intellectuals and scientists of Jewish origins who had contributed to world civilization and to Austria and Germany in particular. She also put into circulation postage stamps dedicated to these Jewish benefactors of humanity.

Just few days before the forced closure of the journal, this last series of stamps was published, not for commerical use, and dedicated to Jewish prominent people

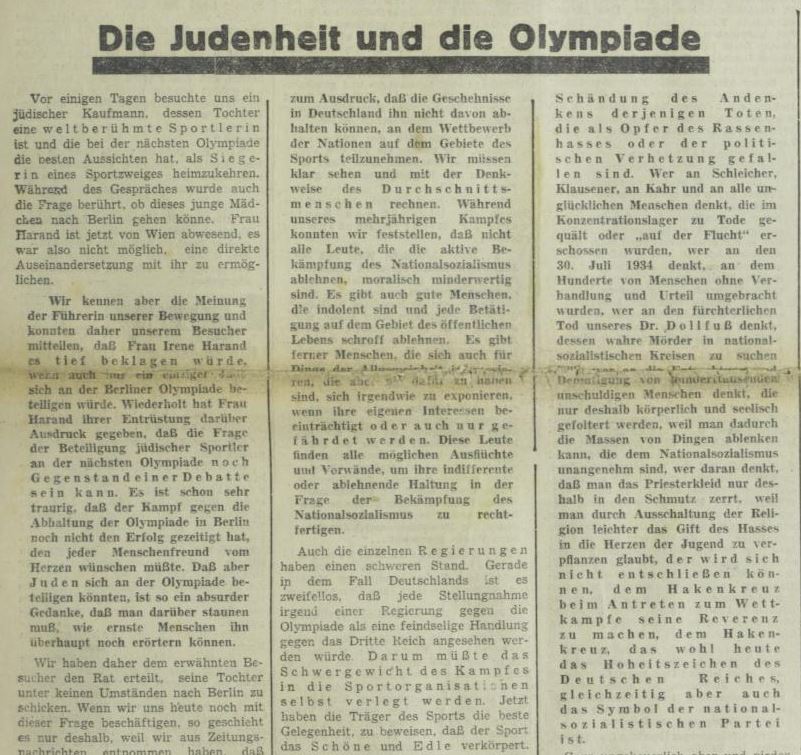

One of Harand’s arguments was for a total boycott, not only by Jews, of the Berlin Olympics since participation would imply an endorsement of racist and anti-Semitic policies. This was an almost unique position in the Austrian panorama in which the Austrian government and the Head of the Patriotic and Sports Front, Vice-Chancellor Starhemberg, adopted different positions. After the assassination of Chancellor Dollfuss in July 1934, Austria had refused bilateral competitions with Germany and, with very rare exceptions personally authorized by Starhemberg, Austrian athletes did not race in international competitions hosted by Germany. The Olympics, winter and summer, would have been an exception and strong representations were made, including by Jewish athletes, to participate respectively in Garmisch Partenkirchen and Berlin. In the issue of Gerechtigkeit on 27 August 1935, Harand had no doubts that this would be a mistake. Nazis were treating Jews appallingly and Jewish athletes had no right to compete in the Olympic qualifiers. Even non-Jewish athletes should feel the shame of not being able to compete with their Jewish colleagues and the Olympic venue must be changed, taking away that privilege from Berlin. Harand even hoped for a political shift in Germany.

Right: Harand delivering a speech on the radio

Left: Photo of Harand taken from the US journal Warren Times Mirror dated 16 Feb 1940

On 19 September 1935, Lewald, the President of the Organizing Committee, announced that Jewish athletes would be able to compete, but Harand denounced him as a collaborator in the Nazi project of world domination and argued that Tschammer von Osten was the true leader of German sport. Exceptions might be made, but this would not change the situation for Jews in Germany. By 5 December 1935, Harand was aware that Berlin would definitely be hosting the Olympics and the journal reported an anonymous interview with the father of an Austrian athlete who was likely to be an Olympic competitor, stating he was strongly opposed to participation. Harand herself has no doubts that Jewish athletes should not compete in Berlin when their community was being humiliated, persecuted, and eliminated. She knew that in the Jewish sports community, not only in Austria but also in other countries, there were doubts about any boycott. Another article in the same issue defined the IOC President Baillet Latour as a supporter of Nazi politics.

Reproduction of first page of Gerechtigkeit in which Harand wrote about Jews and Olympics

Although Jeremiah Mahoney, head of the Amateur Athletic Union, advocated for a US vote against participation, on 8 December 1935, the AAU decided to participate in the Olympics. In February 1936, Austria took part in the Garmisch Partenkirchen Winter Games and Harand did not return to the subject of Berlin until 11 June 1936 when she raised the prospect of a possible tourist boycott. On 9 July, she dedicated a short paragraph to the refusal of the Austrian Jewish swimmer Judith Deutsch to make herself available for Olympic selection, leading to a federal ban for eighteen months. Harand argued that Deutsch should be applauded for her actions, although, excluding comments in the Jewish Press, hers was a lone voice. Harand had always supported the government, even justifying its authoritarianism on occasions, but her stand was now bringing her into conflict with the authorities. According to what has emerged from archives available in Moscow, the police now began to harass the non-political Harand Bewegung. The government officially maintained freedom for minorities but wanted silence from critics in order to keep normal relations with Germany following the agreements of July 1936 that were attacked by Harand because they gave free rein to Nazism in Austria. Even before the Anschluss, Harand gradually distrusted the government, which allowed Nazi and anti-Semitic forces preach their poisonous word and “style” in Austria.

Photo of Deutsch. There are of course the usual photos of her on the Internet. This is extracted from a UK journal.

After the Games, Gerechtigkeit dedicated a good deal of space to recalling Jewish victories in Olympic history. On 22 October, Harand returned to the case of Deutsch, to whom the swimming federation had extended the disqualification to two years, proposing a complete amnesty and Starhemberg personally intervened to bring the penalty back to the initial eighteen months. On 16 September 1937, Harand argued that the majority of Austrian people were against anti-Semitism and she was hopeful that the Church, and the cooperation of democracies such as the United States, Great Britain, and France, would counteract the Nazi menace. By the time the Anschluss took place, Harand was in Great Britain. The Nazis had defeated her on the Berlin question in 1936 and forced her into exile, where she continued her battle, never abandoning her commitment to Gerechtigkeit, in favor of peace and friendship between Jews and Christians. Later, when in the United States, she helped the emigration from Central Europe of many persecuted people and Yad Vashem nominated her as Righteous among Nations in 1968. She died in 1975.

Article © of Gherardo Bonini