Efforts were made in late 1895 to bring the women’s cycling champions of England and France – Mrs Clara Grace and Lisette Marton – together to race each other in Paris or London. According to the American weekly The Referee & Cycle Trade Journal, the race was initially proposed by Mr Geo W. Atkinson of the British daily newspaper Sporting Life in a letter to Lisette’s coach, Choppy Warburton, to build on the women’s encounter at the first successful London six-day race at the Royal Aquarium on 18-23 November 1895. This event had seen Lisette come second overall to English rider Monica Harwood, while Clara Grace had won separate 15, 20 and 50-mile scratch races at the same venue the following week. The 20-mile scratch race may have particularly sparked interest as it had seen Lisette and Clara Grace fiercely battle each other alone after another English competitor, Nellie Hutton, had been dropped and two additional French riders had abandoned the race. Choppy Warburton had subsequently issued a challenge to any rider “in the world” to race Lisette over 100 kilometres (62 miles) and in a published letter in Sporting Life in December 1895 to Arthur Walter Gamage, the owner of the Gamages department store in Holborn, Warburton referenced an advertisement publicising Grace’s victories over Lisette at the Royal Aquarium using a Gamage racing bicycle, implying that she would be the ideal opponent. The challenge was subsequently accepted by Clara Grace to take place by the end of February 1896 in Paris with a rematch originally proposed the following month in London.

The one-off 100-km race finally took place on Thursday 5 March 1896 at the Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter Velodrome) in Paris then located in the majestic Palais des Arts Libéraux (Palace of Liberal Arts) on the Champ-de-Mars. Up to 2,000 spectators turned out to witness the spectacle, while newspapers in France and the UK detailed the race in minute detail the next day. The International Herald Tribune also covered the race, posing the question to its female readership: “Pretty maid or grande dame, how long do you suppose it would take you to cycle 100 kilometres?”

-

The Palais des Arts Libéraux (Palace of Liberal Arts) was originally built for the 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris.

Source: US Library of Congress.

A starting gun was fired at quarter past two in the afternoon with an accompanying band playing rousing music to keep the spectators musically entertained over several hours as the racing cyclists rode repeatedly around and around a banked oval wooden track. The race was refereed by Mr Atkinson representing Sporting Life with a British National Cyclists’ Union (NCU) representative the timekeeper.

Clara Grace, always known as “Mrs Grace” in newspaper and journals articles, was dressed in all-white with a Union Jack shawl proudly draped across her left shoulder. She took an early lead on her Gamage racer keeping on the wheel of a tandem bicycle ridden by two male pacers until the twelfth lap when Lisette, dressed in a light blue jersey and dark blue bloomers, closed in on her English rival and overtook her, lapping Grace at the five-kilometre mark. Assisted by pacemakers on a triplet bicycle and egged on by Choppy Warburton at the side of the track as well as a raucous home crowd, Lisette continued to put distance on her rival, covering the first 50-km in a time of one hour, 19 minutes and 46 seconds. She eventually crossed the line in two hours, 41 minutes and 12 seconds – a new women’s record for the 100-km distance and one that actually surpassed an officially-recognised men’s record for the same distance set by Frenchman Jules Dubois several years earlier.

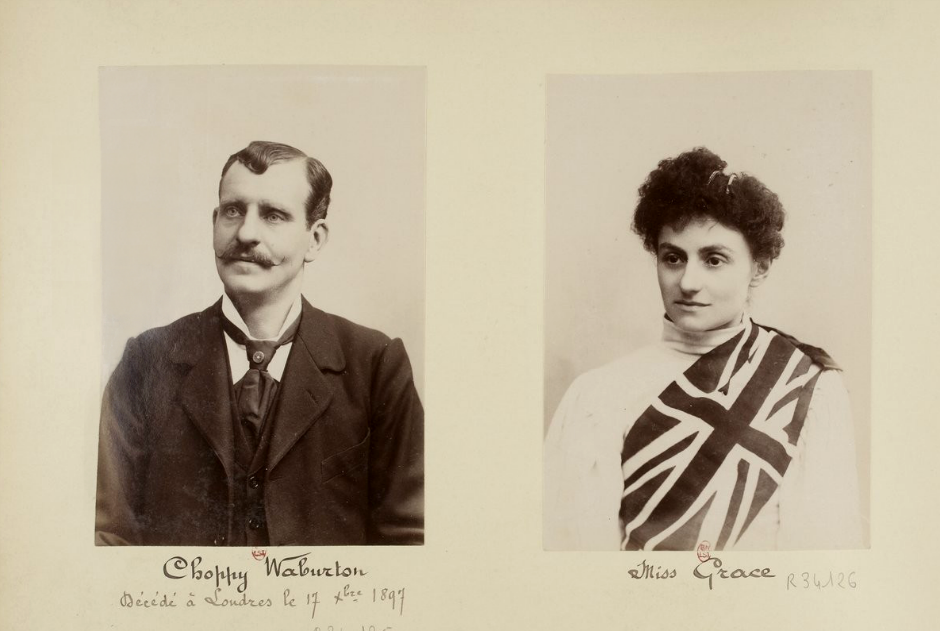

-

Choppy Warburton (left) and Clara Grace (right).

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF).

The riders sportingly shook hands once they had dismounted from their bikes at the end of the race. The spectators chanted Lisette’s name as she was presented with a bouquet of flowers, prize winnings of £100 and a tricolor sash. A correspondent for the French cycling journal Véloce-Sport described his sense of national pride at Lisette’s win and how he wished that ‘La Marseillaise’ had been played.

Lisette’s victory was partly attributed to the new British-made Simpson Lever Chain on the French-made Gladiator racing bicycle that she rode upon. It was claimed that the novel chain, which was designed by the London-based civil engineer William Simpson in 1895, improved drivetrain efficiency, enabling the rider to go faster while generating less power and thus reducing fatigue – ‘marginal gains’ 1890s-style, to coin an often over used phrase used in present day cycle racing. Lisette’s victory using the chain was then publicised in advertising literature by the manufacturer, the Simpson Lever Chain Company based in London and Derbyshire.

The poor performance by Clara Grace, who had been lapped 16 times by the end of the race, was blamed on ill-health and her preparation following her arrival in Paris by “overtraining” on the track prior to the encounter. Sporting Life additionally attributed her defeat on being supplied with a different bicycle to the model that she usually raced upon, which had “longer cranks than she was accustomed to, and the saddle too forward”.

-

Jules Beau photograph of Lisette. Note the Simpson Lever Chain on her Gladiator bicycle and the accompanying caption referencing her time and win over Mrs Grace.

Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF).

Both of these ‘cycliennes’ were clearly then stars of the cycling track in the 1890s, Lisette especially, but who were these trailblazing women? Extensive genealogical and archival research by this author presented over the next two parts provide some new and fascinating insights into these two lady racers during an era of improving Anglo-Franco diplomatic and cultural relations.

Article © Mike Fishpool

For Part 2 of the series see – bit.ly/2DBPsBF