To read Part 1 of this series click HERE and Part 2 HERE

The Running Career Revived

Violet Piercy was 42 when the case came to court. It would not have been unreasonable to retire from athletics. But as her perseverance with the slander action demonstrated, she was not a quitter. In the following May an American paper, the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, published a picture of her in training, with the caption CHAMP SEEKS TO BETTER RECORD:

Miss Violet Piercy, world’s champion woman marathon runner, being given instructions by her trainer from a pace-making car at Ruislip, London, where she is training in the hope of beating her own record.[i]

The run took place on 27 May, 1933, with Charles Packford, of The Sporting Life, as referee and timekeeper. Once again it was from Windsor to London and was said to have been over “a slightly varied, but longer course” of over 26 miles, “running through thousands of cheering people” and finishing on the stage of the Shepherds Bush Empire, in 4 hours 25 minutes. She had been hampered by a slight thigh strain and by a storm of heavy rain and icy wind for the last thirteen miles. Her feet kept slipping on the wet roadway, presumably because she persisted in running in those leather shoes with the cross strap.[ii]

The newspaper’s involvement is significant. The Sporting Life had been associated with the Polytechnic Harriers marathon since 1909, the year after the official distance was established. It was the main marathon for men in Britain, and the magnificent Sporting Life trophy was confirmation of the commitment of the newspaper. It seems likely that under their stewardship Piercy was running this time over the official Windsor to London course except for the variation at the finish. The Shepherds Bush Empire was under a mile past the White City stadium, where the Olympic marathon had finished. The route taken is not mentioned in the press reports so far examined, but we know she ran on the official course in her unfinished marathon of 1928, so it seems reasonable to assume that this run five years later was along the same roads. The time she took fits neatly with her other performances.

Before the year’s end, she was off on another road run. Mr Packford of the Sporting Life turned out again in the open car on 28 November, when Piercy ran 22 miles from the Slough end of the Colnbrook by-pass to Mitcham. Not for the first time, she had to contend with extreme weather, a storm of rain and sleet. She was advised to retire at 15 miles, but battled on and finished in 3 hours 45 minutes.[iii] A picture published in Prensa, a Spanish newspaper, shows her wearing the same strapped shoes that she favoured throughout her career.[iv]

Violet in her favoured footwear

Source: La Prensa 10 December 1933

More Running and More Litigation

As a member of Mitcham Ladies Athletic Club, Piercy took part in several cross-country races early in 1934. The women’s junior national championship actually took place on Mitcham Common (the term “junior” meant that the race was open only to competitors who had never placed highly in the WAAA national race). She finished 65th, the last of the Mitcham runners to finish.[v] It was rare for Piercy to face competition and when she did, she generally finished well down the field. Her forte was her staying power. She seems to have been a runner of moderate ability who gained attention because she attempted distances no other woman was willing to consider.

In April, a bizarre item in the Baltimore Sun reported that Piercy had lent her umbrella to a deaf and dumb woman to protect her new hat from rain. The woman dumped the umbrella in a dustbin and Piercy successfully sued her and was awarded 2 shillings and sixpence in damages by a court in Croydon.[vi] The term “litigious” is occasionally applied to people who seek legal redress on the slightest pretext. Piercy seems to have been a prime example.

Daily Mirror 27 July 1934

There was more positive publicity later in 1934, when she organised the first-ever road race for women, over 3 miles. In the South London Press, she claimed that “on every side women are clamouring for longer and more exacting stamina tests.” She predicted that the time would come when women’s runs from London to Brighton (52 miles) would be no more unusual than men running the distance. She expected a line-up of “well over fifty women athletes from all the leading clubs”. The interview went on to state that she held “fully recognised women’s records over four, five, ten, twelve, fifteen and twenty-two miles” as well as the full Windsor to London marathon course. An insight was given into her diet and training. She “places great faith in pure lemon juice and brown sugar” and her training ritual started with two outings a week over comparatively short distances, building gradually to the point where “shortly before the actual race, she is running practically the full marathon course”.[vii]

The race took place at Mitcham in October and attracted only thirteen starters. As the organiser, Piercy did not take part. The winning time of 18 minutes 5 seconds by Peggy Camfield was faster than Piercy ever managed.

Sunday Mirror 21 October 1934

The Monument Stunt

Violet Piercy had a talent for publicity few sportswomen of her time could match. She would routinely contact the press to announce that she was to attempt new records. In 1930 she was filmed for Pathé News running through the streets of South London with a tame sheep on a lead.[viii] In 1935 she announced a new personal challenge. Starting from the Dick Whittington statue at Highgate she would run 5.25 miles to the Monument in central London and then, without pause, run up its 311 steps.[ix] The attempt was well supported. “Huge crowds lined up outside her Clapham home to see her start out,” the South London Press reported, and, “at points on the course the police had difficulty keeping back the sightseers.” After successfully performing the stunt she spoke up once again for the cause: “No other woman or man has yet attempted this. I did it to prove that a woman’s stamina can be just as remarkable as a man’s.” Rashly she added, “My next effort is to be an attack on the women’s mile road record. This is rather a short distance for me, but I am told I have speed as well as staying power, and I am confident I shall lower the existing time.”[x]

The Monument stunt was widely reported in the national and international press and probably gained more coverage than any of Piercy’s runs. In the Western Daily Press at the year’s end she was listed as one of the Women of 1935: “For novelty, the record established by Miss Piercy wins first place.”[xi]

Violet Piercy’s Monument run

A marathon beyond dispute

At the age of 46, Piercy ran her last Windsor to London marathon, and there could be no disputing the distance she covered, because on this occasion she was allowed to run the Polytechnic Harriers’ course on the day of the men’s race, 13 June, 1936. She started shortly before the 78 men and ran steadily to the finish at the White City stadium, in no way distressed. Her time was 4 hours 25 minutes and she was said to be “not the slightest bit out of breath.” According to the Daily Express “she made some men runners look not too good.”[xii] In an interview she stated:

I was not really competing with the men runners. I only wanted to prove that women could stick the distance. I have done this marathon three times.[xiii]

The Daily Mirror reported the run under the headline PROOF![xiv]

The last years

There is no firm evidence that Piercy ran again, although she called at the Daily Express office in 1937 and told the columnist Trevor Wignall that she was planning to attack the 2 miles record[xv]; and in 1938 she informed the Daily Mirror that she was out for a double record, first the half-mile and then within a few minutes the 4 miles.[xvi] Such ambitions were, sadly, divorced from reality. We hear of her again in Croydon in 1937 and 1938, pursuing Dr Coplans in the bankruptcy court for failing to pay the damages and costs awarded in the 1932 slander action.

The 1939-45 war seems to have put a stop to her activities on the roads, in court and in the media. Electoral registers show a Violet Piercy living in Streatham between 1946 and 1952 and on the borders of Streatham and Tooting in 1957 and 1958. In 1945, the BBC contacted her in Streatham with a view to contributing to a suggested sports programme, but nothing came of it. However, in February, 1950, the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph had a small item following on from a piece about Jack Holden, the winner of the men’s race at the Empire Games:

Another Marathon runner who is still as fit as ever, though shy of giving her age, is Violet Piercey. Fifteen years ago she established herself as Britain’s leading woman distance-runner. Just to show her fitness when challenged, she ran from Hampstead to the Monument and then sprinted up the steps to the top. She attributes her success to moderate drinking and practically no smoking. She has, for example, had only two cigarettes since Christmas.

Extensive searches have failed to trace any record after 1958. There is no firm evidence that she went abroad, married or died. It seems remarkable that such a publicity-conscious woman didn’t make herself known to the press in 1948, when the Olympic Games were held in London, or in 1964, when another British woman, Dale Greig, at last completed a marathon and set a new time of 3 hours 27mins 45sec.[xvii]

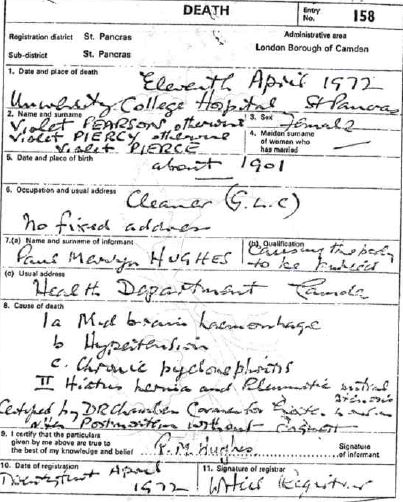

There is one possibility, poignant for anyone with an interest in the story. In April, 1972, an elderly woman of no fixed address was admitted to University College Hospital in London and died there of a brain haemorrhage, hypertension and chronic pyelonephritis (kidney-related infection). She seems to have been unable to speak her name clearly, because it appears on the death certificate as Violet Pearson otherwise Piercy otherwise Pierce. Her occupation is given as cleaner for the GLC (Greater London Council) and her date of birth was estimated as “about 1901”.[xviii] Camden Council arranged her burial. She had an estate worth £2500 (about ten times more in modern money value), presumably on her person in the form of cash and jewellery, that was never claimed and passed to the state.

Could this homeless woman have been the once-famous runner? The estimate of age appears to rule this out. Violet Piercy was born in 1889. However, I showed the certificate to Professor Bernard Knight, an eminent Home Office forensic pathologist who has carried out thousands of autopsies, and he wrote back:

The statement on the death certificate that she was born ‘about 1901’ is peculiar, as no retrospective estimate from 1972 can be that accurate – they could just as well have said 1889 or 1905, so I assume they dated her on some other circumstantial evidence, or just a throwaway guess. I doubt that mere inspection of a corpse can estimate the age ten years either way. It’s not like a pathological examination, where x-rays of bones etc. can be done, though even there accuracy is impossible except in people up to about 25 years of age. I doubt also if anything useful about her age could be gleaned from a post-mortem.[xix]

So the identity of this old lady called Violet remains an open question.

The Violet Pearson AKA Violet Percy Death Certificate

Conclusion: The Later Reputation

A bigger mystery is why Violet Piercy’s several marathon runs inspired no other woman to try the event. Gertrude Ederle, the channel swimmer of 1926, started a trend that has continued ever since. Yet it was 1963 before another woman completed a marathon run, and that was an American, Merry Lepper, who had probably never heard of Piercy. How could such a publicity-wise runner be airbrushed from history?

Two veteran members of Mitcham Athletic Club were contacted for their recollections. Dorothy Tyler wrote back, “I only remember Violet because of the fact that she ran up steps in some large building. I never spoke to her. I thought she was a walker.”[xx] Denis Brickwood also never spoke to her, but remembered her running around the News of the World track at Mitcham, always alone. “The opinion among the other members was that she was a bit strange, if not in fact weird, and certainly a loner.”[xxi]

There must be a suspicion that Violet’s oddities were off-putting. Her pursuit through the courts of individuals who upset her, even when there was little expectation of covering her costs, suggests she was not a person one would choose to cross.

Eccentricity can be alienating, but not always. Dr Barbara Moore, the long distance walker of the 1960s, was regarded as eccentric, yet started a craze taken up by hundreds who had never tried such distances before.

Of course the governing bodies of national and international athletics sought to limit women to running no more than 1 mile/1500m until as late as 1968 in Britain and 1984 in the Olympics and this may explain why a maverick like Piercy isn’t mentioned in early histories of the sport, which are usually divided into chapters based on the events of the standard track and field programme. The widely believed myth of the 1920s and 1930s that the strain of endurance sports might adversely affect child-bearing may have been discarded, but the possibility of overstrain was a limiting factor for several decades after the war.

Looking back from a world where mass-participation by women in marathon running is commonplace, it seems remarkable that no one else attempted the distance before the 1960s and even more remarkable that one woman’s ten-year crusade a generation earlier had no enduring influence at all. However, Violet Piercy now has her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[xxii] Who could doubt that she earned it?

Acknowledgements

Mark Curthoys, Peter Jefferson Smith, Kevin Kelly, Andy Milroy and Alex Wilson contributed substantially to the research and I wish to record my thanks to them.

Article © of Peter Lovesey

References

[i] Pittsburgh Post Gazette 15 May, 1933

[ii] Sporting Life 29 May, 1933

[iii] Sporting Life 28 November, 1933

[iv] Prensa (Spain) 10 December, 1933

[v] Mitcham & Tooting Advertiser 22 March, 1934

[vi] Baltimore Sun 8 April, 1934

[vii] South London Press 16 October, 1934

[viii] www.britishpathe.com/video/mary-had-a-little-lamb-1/query/Piercey

[ix] South London Press 22 March, 1935

[x] South London Press 2 April, 1935

[xi] Western Daily Press 24 December, 1935

[xii] Daily Express 27 February, 1937

[xiii] Straits Times, Singapore 28 June, 1936

[xiv] Daily Mirror 15 June, 1936

[xv] Daily Express 27 February, 1937

[xvi] Daily Mirror 4 October, 1938

[xvii] In 1972, Greig also became the first woman to run from London to Brighton, the feat predicted by Piercy in 1934.

[xviii] Certified copy of an entry of death for Violet Pearson otherwise Violet Piercy otherwise Violet Pierce 11 October, 1972

[xix] Private email correspondence 29 February, 2012

[xx] Private correspondence, undated, 2012

[xxi] Interview with Kevin Kelly, 2012

[xxii] www.oxforddnb.com/index/103/101103698/

![“And Then We Were Boycotted” <br> New Discoveries About the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 3](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Marco-Giani-Boycotted-Part-3-440x264.jpg)

I think that Violet Piercy should be honoured with a commemorative plaque. Have you any idea if there are any women’s sport organisations who might be interested in sponsoring a commemorative plaque to Violet on her Battersea home 21 Leathwaite Road as it is unlikely that an application to English Heritage would be successful.

I have organised plaques for the Battersea Society and the process is relatively easy. It would require getting permission from the owners of the property , commissioning a plaque from eg Signs of the Times for around £400, installing and organising an unveiling event. Sometimes organisations ask for contributions for it and people are often happy to subscribe.