Please cite this article as:

Fishpool, M. The Wheeling Wonders of London: The Lady Cyclists of the Royal Aquarium’s First Professional Women’s Cycling Tournament, In Day, D. (ed), Playing Pasts (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2020), 56-71.

ISBN paperback 978-1-910029-56-5

Chapter 4

______________________________________________________________

The Wheeling Wonders of London: The Lady Cyclists of the Royal Aquarium’s First Professional Women’s Cycling Tournament

Mike Fishpool

______________________________________________________________

Abstract

The cycling boom of the late nineteenth century saw cycle racing grow as a professional sport, involving both genders. Young women raced on safety bicycles around a wooden oval track in entertainment venues and velodromes, exerting themselves beyond what some parts of society may have considered to be appropriate for the fairer sex. Women’s cycle racing briefly captured the public’s imagination enabling all social classes to spectate at the races or read about it in popular newspapers. This chapter recalls London’s first professional women’s cycle racing tournament held in late 1895 at the popular Royal Aquarium and Winter and Summer Garden located in Westminster, one of many races that were held at the venue until 1901. It recounts the racing, the press coverage, and then delivers a biographical history of some of the English riders.

Keywords: Sport, Entertainment, Gender, Women’s Cycling, Cycle Racing.

The Six-Day Race, November 1895

Since opening in Tothill Street, Westminster in January 1876, the Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Garden had become a major London venue of entertainment, lectures and exhibitions. In late 1895, it held a novel sporting and entertainment event, becoming the first major London venue to hold women’s professional cycle races. The competition built on women’s races that took place in the summer of 1895 in Hull, Scarborough, Greenock and Edinburgh as part of a British cycling tour, as well as in Plumstead, London. It was the Royal Aquarium’s most financially successful event, earning it £4,695 during the first week.[1] Billed as a ‘twelve-day race’ and taking place in November-December 1895, it featured two separate six-day races each covering one week – except for Sunday to respect the Christian Sabbath. A soup-bowl wooden track was laid in the Royal Aquarium’s main hall, measuring ten laps to the mile or a total of 11,300 feet (3,453 metres).[2] Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper detailed the track, stating that it ‘ran round the ground floor, and was formed of pine planking firmly fastened to joists of the same wood, and fenced in by railings. At the east and west ends, where curved round, the outer edge was raised six feet above the inner, to prevent riders flying off at a tangent when negotiating the arc’.[3]

Figure. 1. The Royal Aquarium.

The first six-day race started on Monday 18 November and finished on Saturday 23 November with 20 women entering, comprising 12 French and eight English riders.[4] Organizers were sent to Paris to recruit riders, who were provided with free travel to England, discounts on first class rail travel and free hotel accommodation.[5] Adverts may have also been placed for the racers – there was at least one advertisement published in The Era in September 1895 that pointed to the location and potential time required to race on the track each day, stating: ‘Wanted, Ten Lady Cyclists, thoroughly competent to ride in and about London for five hours a day. Fair Ladies preferred’.[6]

The women riders were paid £3 to £10 a week for racing. The Pall Mall Gazette reported that this was topped up through prize money and prizes supplied by the Royal Aquarium and individual companies. There was also money paid by bicycle manufacturers and the newspaper identified a wealthy unnamed male benefactor who presented money to riders he liked, providing an example where it says: ‘One who was present at this idyllic scene suggested that ‘Miss Hutton had ridden very well’. The man of the cheques agreed to this, and, adding that he “must do something for her”, handed over a cheque for £50’.[7] The South Wales Echo added that the man also awarded the first four positioned in the race £10 each, while the winner received £25.[8]

The riders were dressed in coloured clothing to enable the spectators to identify them. Berrow’s Worcester Journal described their appearance: ‘The costume […] was a matter which excited much comments. They all wore knickerbockers […]. The French ladies wore a tightfitting jersey which formed one piece with the breeches and several wore sashes of distinguishing colours. The English ladies wore pretty blouses decked with ribbons, and their hair daintily dressed, while the French ladies wore their hair in plain ‘bobs’ at the back’.[9] The Manchester Guardian added that the ‘French girls nearly all wore golf jerseys, full bloomers to the knee, and belts or silk sashes. The English girls had a variety of costumes, about the ugliest being a tight-fitting tailor bodice, worn with knickerbockers, and a skirt drawn up with cords into a tunic. A competitor aged fourteen was got up in tight satin breeches, embroidered stockings, and an elaborate blouse with a scarf’.[10]

The opening day saw the women split into two sections riding a total of five and a half hours. The first section of ten women raced from 14:20 pm in the afternoon, followed by a second section at 16:45 pm, which contained some of the race favourites. Each section returned to the track again for 90 minutes in the evening.[11] Two representatives from the newspaper Sporting Life, which organized the race, were appointed referee and timekeeper. It was started by Edward Du Plat, the Royal Aquarium’s exhibition organizer under the direction of the managing director, Josiah Ritchie.[12] The first day was eventful for the spectators with numerous crashes and foul play – the English riders complained to referee Robert Watson about their French rivals, alleging that they were blocking them from overtaking on the outer side of the track with the rules preventing overtakes on the inner side. The Evening News reported that ‘this unfairness was so marked that it evoked hisses from the spectators’.[13] A band played during the racing, while spectators could also enjoy the Royal Aquarium’s other various entertainments and novelties, including dancing elephants, boxing kangaroos, ballet, acrobats, magicians, dancers and comedians. Admission started at one shilling but eventually rose to half a crown and more by the final night.[14]

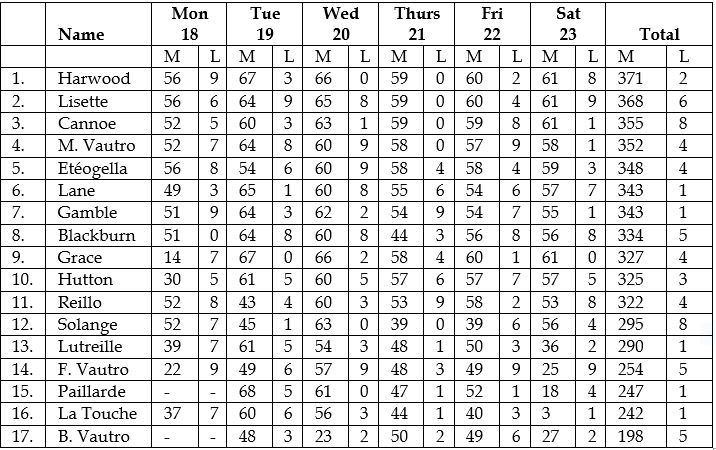

The racing continued during the rest of the week, culminating in the last day with two races in the evening lasting 90 minutes. The final race featured the French riders Lisette Marton, Marcelle Vautro and Gabrielle Etéogella, and the English riders Monica Harwood, Mrs Grace, Rosina Lane and Nellie Hutton. It evolved into a battle between Harwood and the French champion Lisette. Mrs Grace took up the role of pacemaker as Harwood wearing ‘a Union Jack sash’ was hotly pursued by Lisette. Sporting Life described the end of the race: ‘At last the whistle blew, and amidst shouts, cheers, and waving of hats, the end came to one of the most sensational races on record’.[15] It was a victory for Monica Harwood who rode a total of 371 miles and two laps during the entire six days compared to Lisette’s 368 miles and six laps. Mlle Cannoe (or Cannac) finished third – she was to be victorious overall in the next six-day race on 2-7 December.[16]

For her win, Harwood was awarded prize money of £100, a purse of gold, a gold and pearl diamond watch, and a gold diamond bracelet. Other prizes for the racers included champagne, fountain pens, clothing and bicycles.[17] There was just over 22 hours of racing during the week. The newspaper Fun stated that ‘The ‘lady cyclists at the Aquarium’ entertainment is not so dreary as it sounds. One felt quite a glow of national pride when, at the end of the first week’s racing, Miss Harwood (England) was returned victorious over her French rivals. Then the band played ‘Rule Britannia’. She rode splendidly and answered gamely to the many shouts of ‘Arwood! Arwood!’ that sprang from countless throats’.[18]

Table 1. Results (M = Miles, L = Laps) [19]

Newspapers provided exciting day by day accounts of the races, but a few were critical. It inspired a satirical article that was originally published in St James’s Gazette, which described the racing as ‘the new (and particularly manly) British Sport’.[20] The article was later expanded upon in The Weekly Telegraph as ‘Ladies and Laps: A Satire on the Aquarium Cycling Show’.[21] It provided a humorous insight into attitudes to London’s first women’s six-day race, reflecting the mix of press viewpoints and featuring a mix of social classes and genders that attended the races. The spectator characters include a ‘round-shouldered youth’, who was there just to see how many of the racers crashed, evoking the kind of young person that moralists feared could be easily influenced into developing an unhealthy fascination with blood and violence. A virile bald-headed ‘reprobate’ shows more interest in the attractiveness of one rider than the racing, while a young doctor ponders the long-term health risks from cycling. The characters generally ridicule and criticise the racing, calling it ‘revolting’ and to be stopped by the police. Despite this, they still agree to return for the next race. The riders are depicted as typically fitting the views and debates regarding women during the period. One rider is described as fragile and in poor health, while one French rider is portrayed as masculine and uncouth, appearing in public smoking a cigar, swearing and dressed in men’s clothing and a massive pair of bloomers. The newspaper Fun was critical that the women did not wear clothing that flattered their figures, stating: ‘the costumes were disappointedly all round – absolutely round – and baggy. Same old pillow-cases, divided by two: so disappointing! We knew how men dressed […]. But the costumes were grim, and virtuous, and ugly – Chantesque in piety! […] Even the shapely calves looked wan and weedy under those infernal, baggy sacks of ‘knickers’’.[22] The American cycling journal The Referee & Cycle Trade Journal was especially scornful, calling the event ‘a disgusting exhibition’ and describing the supposedly ‘chic’ French riders as having ‘contorted faces, bent backs, hair fair flying wildly around their heads, their costumes soaked in certain spots where perspiration had oozed through’.[23]

The women of the race

Newspapers and the journals of the period generally provided scant information on the riders. Cycling-specific journals like The Hub: An Illustrated Weekly for Wheelmen and Wheelwomen published more in-depth illustrated interviews. Modern online digital archives and censuses now enable sports historians to build detailed profiles on these women racers for the first time in 120 years. The English riders are fairly uncomplicated to research, and some are profiled in this paper, but the French riders prove to be more difficult due to availability of online archival material and because the French press did little to actually profile their riders at the time, despite delivering a lot of coverage of the racing. As mentioned earlier, there were 20 women involved but only 17 riders finished the entire event.

This author has previously extensively researched and published papers on the French champion Lisette (real name Amélie Le Gall).[24] The other French riders – Gabrielle Etéogella, Nellie La Touche, Lucie Lutreille, Henriette Paillarde, Fanoche Vautro, the sisters Bèany and Marcelle Vautro, and Mademoiselles Cannoe, Solange, Reillo and Aboukaïa – are yet to be fully researched with little information to construct profiles based on genealogy research, racing careers and what they did after retiring. In the case of the latter rider, she did become much more famous after her cycling career, initially as an acrobat and eventually as a pioneering aviation pilot. Mlle Aboukaïa actually abandoned the first six-day race at the Royal Aquarium after the first day, taking no further part in the racing. The Vautro sisters, Marcelle and Bèany (real name Melanie Ann), were regulars at the Royal Aquarium races, as well as in France. They were born in Montluçon in central France in 1880 and 1878 respectively. Marcelle was the first of the French riders to race in Britain, having taken part in the women’s cycle races during the summer of 1895.[25]

The English riders comprised Monica Harwood, Mrs Grace, Rosina Lane, Rosa Blackburn, Clara (or Clare) Gamble, Nellie Hutton, Lilian Adair and Miss Benham. Lilian Adair and Miss Benham withdrew on the first day and did not appear in any further cycle races after the first event in London, making them difficult to research. Miss Benham was actually pulled off the track ‘on account of her erratic steering’, after bringing down a number of riders.[26] There is little information on Miss Gamble, who finished seventh overall, but she continued racing at the Royal Aquarium up to 1897. If taking into consideration that all the English racers were based in and around the London area, the only individual identified as a possible candidate for this rider was a Clara Jane Gamble, born in 1867 or 1868, who lived in Brentford.[27]

Mrs Clara Grace, who finished ninth, was profiled by this author for the Playing Pasts website in September 2018 and May 2019.[28] She was born Clara Simmons in Redbourn, Hertfordshire in 1865 and married William Grace in 1885, later relocating to Wood Green and bringing up four children (three daughters and one son). Clara started cycle racing in 1894 and was crowned the ‘champion of England’, gaining stature after she set women’s endurance road records in 1895-1896. She went on to win races at the Royal Aquarium and Bingley Hall, Birmingham. After a bout of illness that prevented her from racing in 1897-1898, she retired from cycle racing in 1899.[29] Nellie Hutton was just 14 when she raced at the Royal Aquarium in November 1895, finishing in tenth position overall and was awarded a prize for the ‘neatest costume’.[30] She was born Ellen Emma Hutton in 1881 in St Luke’s, Middlesex and was the oldest of three children (two daughters and one son) belonging to William and Ellen Hutton living in Petherton Road in North London.[31] William ran a bicycle shop, also manufacturing his own bicycles under the ‘Petherton’ brand. It was one of these that Nellie raced on.[32] Her mother participated in several races in the summer 1895, coming up against Nellie a few times.[33] Nellie was a regular at the Royal Aquarium and had some successes in races held at the Olympia in West Kensington during 1896. She later married Edmund Henry Parnall in 1901. In the 1911 census, Nellie and Edmund Parnall were living in Ilford with four children (three daughters and one son) and one servant.[34]

The untold stories of three English riders

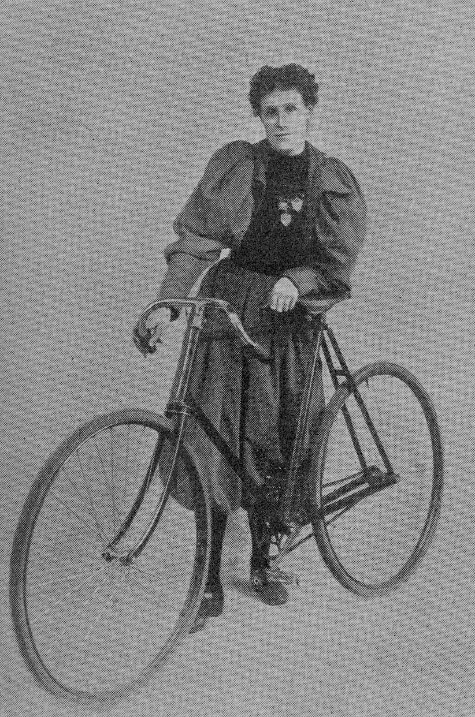

Monica Harwood came into professional women’s cycling at just 18 years of age, beating the accomplished and much-admired French rider Lisette. Monica later became the captain of the Chelsea Rational Cycle Club (C.R.C.C.), which was formed in 1898 to promote rational dress for female cyclists and to undertake weekend club runs. Fellow cycle racer Rosina Lane was the club’s honorary secretary and treasurer, while London-based rider Bèany Vautro was the vice-president. [35]

Figure 2. Monica Harwood, The Hub, 1898

(Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick).

Monica was among one of four riders participating in a specially organized event at the Royal Agricultural Hall in early 1896 that built on the first Royal Aquarium race. It was held to match the best of the English and French women riders with Monica racing one-on-one against the Belgian-born Hélène Dutrieux in a paced 50-mile race on 23 March, which she lost, and coming second and third in a further 50-mile race on 28 March, separated into two 25-mile races that also involved Dutrieux, Mrs Grace and Gabrielle Etéogella.[42] Monica was also among the five women competitors who took part in one-mile races at the Royal Aquarium in January-February 1899, riding on static bicycles on stage – she participated in further static races at the Tivoli Variety Theatre in Glasgow in October that year.[43] Her last races at the Royal Aquarium were a series of sixes held on 3-29 June 1901 before the venue shut its doors for the last time, eventually being demolished to make way for the Methodist Central Hall. Monica came second in the first race on 3-8 June, which featured five riders from the first event six years earlier amongst the 12 competitors, and she won a second six-day race on 10-15 June.[44] On 19 October 1901, she established a British women’s hour record at Putney Velodrome of 24 miles and 780 yards (713 metres), paced by tandems and beating the record that she had previously set.[45] Monica was then reported in March 1902 performing on a small track on stage with two men and another woman named Emilie Golding, who had also taken part in the Royal Aquarium races the previous summer. This group were known as ‘Ransley Troupe’, which was formed in 1899 and managed by a ‘Madame E. Ransley’. It performed at the London Pavilion that month.[46] Monica also assisted a ‘Madame Lizette’ (presumably not the same French rider who was based in the US at the time) racing on a mini track on the stage of the Osborne Theatre in Manchester in August 1902. Further adverts detail ‘Madame Lizette’s Cycling Sensation on the Teacup Track – The smallest and steepest track in the world. 120 laps to the mile’ and ‘Mdme Lizette’s lady cycling sensation, in which a troupe of five cyclists, two of whom are males, give a daring display on a ‘teacup’ track. The track is sloped at an angle of 65 degrees’.[47] With no further reports of Monica’s involvement in these performances after 1902, it can be presumed that she had retired. She married William John Collingham five years later, eventually living in Lambeth where William was employed as a hotel waiter, and raised two sons, William and Norman. Monica Collingham died in 1961 at the grand old age of 83.[48]Monica Mary Harwood was born in 1878 in Buckingham. She was a farmer’s daughter, the youngest of four children (two daughters and two son) belonging to William and Anne Harwood. In 1881, her mother was solely responsible for managing an entire farm of 132 acres in Northolt, Uxbridge in Middlesex, employing three men. The Harwood family relocated to a cottage in Twickenham by 1891 (minus one daughter and one son) and were joined by William Harwood, whose occupation was listed as a ‘retired farmer’. The family relocated again around the time of Monica’s cycle racing career to Staines Road, Bedfont in Middlesex, before Monica, her mother and two brothers moved by 1901 to Bulstrode Road, Hounslow.[36] Nicknamed ‘Monie’, Monica said in an interview in The Hub to have started cycling in July 1895 after being taught by one of her brothers and that it helped improve her health, having been in ‘delicate health’ a few years previously.[37] The Queen: The Lady’s Newspaper stated that she started racing shortly after taking to the wheel under the direction of Clara Grace.[38] Monica raced upon a 10.4 kg (23 lb) ‘Elysee’ racing bicycle equipped with Dunlop pneumatic tyres but switched to Symonds Roberts’ Royal Racer towards the end of her racing career.[39] She would train on the road and track for ‘two to three hours’, two weeks before a race with a preference for paced 50 and 100-mile races. Her first race was in Hull in the summer 1895, an experience that led her to remark that: ‘it was the very first time I had seen a proper track. The high banking quite frightened me, and I imagine it would never be possible to ride round safely. However, I started, and I managed to come third in a two-mile race’.[40] She was one of the main British stars of the track, racing in London at the Royal Aquarium, Newcastle, Sheffield, Southampton and Paris.[41]

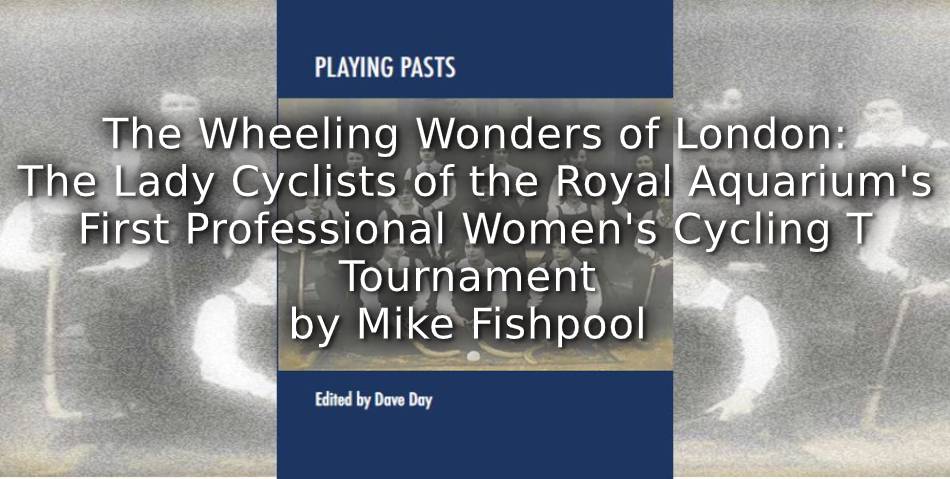

Rosina Lane finished in sixth position in the first six-day race at the Royal Aquarium and was one of two racing mothers, along with Clara Grace. It was her costume that The Manchester Guardian had called ‘the ugliest’ in its coverage of the racing, featuring an innovative skirt designed by Rosina’s sister-in-law Alice Bygrave and marketed for general cycling and walking use as the ‘Bygrave Convertible Skirt’.[49] Her full name was Amelia Rosina Lane and she was born in 1860 in Standish, Gloucestershire. Rosina was one of nine children (four girls, five boys) belonging to James and Elizabeth Lane. In the 1861 census, James was working as a farm bailiff managing 65 acres of land in the Standish area with Ann plus Rosina, three other daughters and two sons; the Lane family expanded with three further sons born in 1861-1868. Ann, Rosina and two sisters plus her five brothers moved to Aston in Warwickshire by 1871 without James (he may have been working in Straiton, Ayrshire in Scotland as a hay baler). Ann, Rosina, and two sons then moved to Chelsea by 1881 where Rosina, aged 21, was working as a machinist. She subsequently married Arthur George Duerre in 1883, a watchmaker by trade, and the couple had relocated by 1891 to 190 Kings Road, Chelsea where they ran a watchmaking and jewellery shop with two daughters, Lilian and Winifred. Rosina had two further daughters in 1892-1894, Alma and Gladys. In the 1911 census, Rosina and the youngest daughter Gladys assisted Arthur in the shop in Kings Road, as well as having a servant and a granddaughter named Lily Bee living with them.[50]

It appears that the Royal Aquarium event was Rosina’s first foray into cycle racing. Arthur Duerre may have been an influence; he was a member of the Chelsea Bicycle and Tricycle Club (Chelsea B&T.C.) and had participated in club races from 1892.[51] Rosina returned for further races at the Royal Aquarium, the Olympia and Birmingham up to 1898. She primarily rode in handicap races and also appears to have ridden as part of a professional pacing team belonging to the Coventry-based Swift Cycle Company. An image of her on a triplet was published in the journal The Sketch in 1895 with Rosa Blackburn and another rider named Miss Murray.[52] In her role as the honorary secretary of the C.R.C.C. with her home acting as the club’s ‘town’ headquarters (Monica Harwood’s Bedfont home was the ‘country’ headquarters), Rosina organized an open international race at Putney Velodrome on 15 August 1898 with the club’s president, Mrs Chaundy.[53] The race provided an opportunity to display rational dress and according to a report on the event in Sporting Life the next day, most of the spectators had originally attended to see Monica Harwood and another rider named Mrs Scott, but neither made the start line. Rosina rode an ‘exhibition mile’ paced by a triplet, while her daughter Lilian rode her first races that included coming second in a one-mile ‘skirts v rational dress’ scratch race.[54] Rosina’s cycling career came to an abrupt end six days after the Putney Velodrome race when she was struck by a horse and carriage whilst cycling in Richmond Park. It led her to go to court to recover damages, being awarded £55. The court case report stated that her ‘bicycle was smashed, the “rational costume” in which she was riding was torn to pieces’.[55]

Figure 3. Rosina Lane, The Hub, 1898

(Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick).

Rosa Blackburn finished eighth at the Royal Aquarium in November 1895, stating that ‘I had terribly bad luck. The track was strange to me, and I had well over a dozen falls, in two of which I ran right up the banking and fell over amongst the people’. Perhaps learning from the experience, she went on to win a 25-mile handicap race at the venue in the same month.[60]

This was not the first time that Rosina would end up in court. Indeed, she had previously been fined for ‘scorching’ (riding at speeds perceived to be too fast for public highways) in Kingston, London and in March 1897, she unsuccessfully tried in Westminster County Court to seek damages from the Royal Aquarium for lost wages.[56] At start of the twentieth century, Rosina was again in the public eye but for all the wrong reasons. In September 1909, Rosina and Arthur were fined a total of £130 for running an illegal betting house in their Kings Road shop. The Gloucestershire Echo said: ‘It was stated that a very large business was done, and that the premises – a jeweller’s shop – were fitted up with tapes and telephones’.[57] The couple’s messy separation that was being pursued through the courts was also played out publicly in various newspapers in 1914-1916 with additional reports during the period suggesting that it was a very traumatic period in their lives.[58] Rosina died in 1938, aged 78.[59]

Figure. 4. Rosa Blackburn, The Hub, 1898

(Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick).

Rosa was born in 1878 in Islington, Middlesex, one of seven children (five daughters and two sons) belonging to Henry Blackburn, a railway signalman, and his wife Annie. The family lived at 12 Hatley Road, Islington.[61] Rosa started racing in the cycling tour in July-August 1895 and then at Woolwich Arsenal F.C’.s Manor Ground, Plumstead on 5 August where she won a half-mile race beating both Nellie Hutton and her mother in the final heat in front of up to 4,000 spectators. She also raced against Nellie’s younger sister Maud (then aged 7!) as well as a Parisian rider in the second heat of this race.[62] After the first twelve-day race, Rosa then rode in Birmingham, at the Olympia and continued to race at the Royal Aquarium, winning overall in December 1896. In eight weeks of racing at the Royal Aquarium at the end of 1896, Rosa rode 3,049 miles, taking a salary and winnings of £140. She won three further sixes and 12-day races at the Royal Aquarium in January and June 1897. At some point, her success enabled her to be crowned the women’s ‘champion of England’, succeeding Clara Grace. She also participated in races at the Royal Agricultural Hall, in Southampton and Paris.[63]

In April 1899, Rosa took part in women’s races that were being held as part of a gala and ‘Olympian entertainment’ held at Balmoral, Belfast in Northern Ireland where she represented England against three other women representing the ‘champions’ of the home nations.[64] She also organized a race the following month at the Putney Velodrome where she rode against a male runner named Harry Hutchens and won a tandem pursuit with Monica Harwood.[65] Rosa started her early racing career riding a Swift racing bicycle but later switched to ‘Triumph’ bike.[66] She promoted Elliman’s Universal Embrocation, an ointment for muscles and joints made out of eggs, vinegar and turpentine, mirroring Clara Grace who regularly recommended the similar St Jacob’s Oil in newspaper advertisements.[67] Rosa was one of the few women to continue racing after major professional women’s cycle racing ended. After winning a six-day race at the Royal Aquarium on 3-8 June 1901 and coming second to Monica Harwood at the venue a week later, she returned to Balmoral Park again in August, racing in several short races and providing a three-mile exhibition race. She then switched to the Tee-To-Tum Athletic Grounds at Stamford Hill, London to take part in women’s races in August and October 1901, and again in May 1902, setting a women’s one-lap record at both events in 1901.[68] Her last races took place at the Recreation Ground, Great Yarmouth on 3 August 1903. The event, which may have been the last professional women’s track races until several decades later, involved six riders in one and three-mile scratch races – some of whom had been regulars at the Royal Aquarium and at other major races a few years earlier.[69] Rosa married Francis James Meddings in 1902; Frank Meddings also dabbled in cycle racing and in 1901 was living at Hatley Road with the Blackburn family – he was listed as an ‘estate superintendent’. The couple had by 1911 moved to Harringay where Frank was working as an assistant estate foreman while Rosa brought up two daughters, Gladys and Evelyn Rosa. Rosa Meddings passed away in 1929, aged 51.[70]

References

[1] The Graphic, January 17, 1903, 15.

[2] ‘The Six Days’ International Ladies’ Bicycle Race at the Royal Aquarium’, The Sporting Life, November 18, 1895, 1

[3] ‘Lady Cyclists at the Aquarium’, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, November 24, 1895, 11.

[4] ‘The Six Days’ International Ladies’ Bicycle Race at the Royal Aquarium’, Sporting Life, November 18, 1895, 1; Mike Fishpool, ‘Miles and Laps: Women’s Cycle Racing in Great Britain at the Turn of the 19th Century – Part II’, Playing Pasts, September 17, 2018, http://www.playingpasts.co.uk

[5] ‘How Ladies Races are Managed: A Chat with Mr Ritchie of the Aquarium’, The Hub: An Illustrated Weekly for Wheelmen and Wheelwomen, September 12, 1896, 221.

[6] The Era, September 21, 1895, 23.

[7] ‘Whirling on the Wheel’, The Pall Mall Gazette, November 29, 1895, 11.

[8] ‘Present for the Lady Cyclists’, South Wales Echo, December 3, 1895, 3.

[9] Berrow’s Worcester Journal, November 23, 1895, 5.

[10] ‘Cycling Notes’, The Manchester Guardian, December 2, 1895, 6.

[11] ‘Ladies Bicycle Races’, The Standard, November 19, 1895, 6.

[12] ‘The Ladies’ Race at the Royal Westminster Aquarium’, Sporting Life, November 25, 1895, 1. ‘How Ladies Races are Managed: A Chat with Mr Ritchie of the Aquarium’, The Hub, September 12, 1896, 221; The Pall Mall Gazette, March 16, 1895, 7.

[13] The Evening News, November 19, 1895, 3.

[14] The Standard, November 25, 1895, 1; Sporting Life, November 25, 1895, 1.

[15] Sporting Life, November 25, 1895, 1.

[16] Sporting Life, December 9, 1895, 1.

[17] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, November 27, 1896, 8; The Standard, November 16, 1895, 1; ‘Bicycle Race for Ladies’, The New York Herald, November 19, 1895, 1.

[18] Frivolets’, Fun, December 3 1895, 1.

[19] Sporting Life, November 25, 1895 plus other articles. Sporting Life gave Rosina Lane a total of 343 miles and 3 laps with 57 miles and nine laps ridden on the final day, most other sources say 343 and 1 lap. The table has been adjusted based on majority reports. Of the 20 women, three riders abandoned the race on the first day and took no further part.

[20] ‘Ladies and Laps’, St James’s Gazette, December 9, 1895, 5.

[21] ‘Ladies and Laps: A Satire on the Aquarium Cycling Show’, The Weekly Telegraph, December 21, 1895, 11.

[22] ‘Frivolets’, Fun, December 3, 1895, 1.

[23] ‘A Disgusting Exhibition’, The Referee & Cycle Trade Journal, December 19, 1895, 34.

[24] Mike Fishpool, ‘Mrs Grace versus Lisette: A Comparison of the English and French Women’s Cycling Champions. Part 3: Lisette – The Women’s Champion of France’, Playing Pasts, May 9, 2019, http://www.playingpasts.co.uk; ‘Lisette – France’s Most Popular Lady Racer’, The Boneshaker, Veteran-Cycle Club, Winter 2018, No 208, 24-34.

[25] Montluçon Baptisms 1877-1878/1879-1880 (2 E 191 74/77), Allier Departmental Archives, http://archives.allier.fr.

[26] ‘Ladies Bicycle Races’, The Standard, November 19, 1895, 6.

[27] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1881, 1891, Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk.

[28] Mike Fishpool, September 10/17, 2018; ‘Mrs Grace versus Lisette: A Comparison of the English and French Women’s Cycling Champions. Part II: Mrs Grace – The Women’s Champion of England’, Playing Pasts, May 2, 2019, http://www.playingpasts.co.uk.

[29] ‘Three Years as a Lady Racer. Some Experiences of Miss Blackburn’, The Hub, March 12, 1898, 231.

[30] ‘The Ladies’ Race at the Royal Westminster Aquarium’, Sporting Life, November 25, 1895, 1.

[31] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1891, 1901, 1911, Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk

[32] Chris Watts, The Boneshaker, 17; The Hub, March 20, 1897, 251-252.

[33] Scottish Referee, August 12, 1895, 4; Glasgow Evening Post, August 15, 1895, 6; Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette, August 15, 1895, 4; ‘Sports at the Manor Ground, Plumstead’, Kentish Mercury, August 9, 1895, 6.

[34] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1911; England & Wales Deaths 1837-2007 (Epping, Essex), Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk

[35] ‘The Chelsea Rationalists’, The Hub, July 9, 1898, 419

[36] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1881, 1891, 1901, Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk; ‘A Chat with a Lady Speed Merchant. Miss Monica Harwood’, The Hub, March 26, 1898, 297.

[37] ‘A Lady Champ Who Rides a Man’s Bicycle’, The Hub, August 22, 1896, 120; ‘A Chat with a Lady Speed Merchant. Miss Monica Harwood’, The Hub, March 26, 1898, 297.

[38] The Queen: The Lady’s Newspaper, December 7, 1895, 1095.

[39] Chris Watts, ‘The Royal Aquarium and Summer and Winter Garden, Westminster’, The Boneshaker, Summer 2007, No 174, 17; ‘Once upon a time or your perfect bike (especially for the Gentle Ladies)?’, Fossilcycle, https://fossilcycle.wordpress.com.

[40] ‘A Chat with a Lady Speed Merchant. Miss Monica Harwood’, The Hub, March 26, 1898, 297.

[41] Newcastle Courant, January 4, 1896, 4; Sporting Life, February 4, 1899, 2; Sporting Life, May 6, 1899, 7.

[42] London Evening Standard, March 24, 1896, 3; South Wales Daily News, March 31, 1896, 7.

[43] Sporting Life, January, 24, 1899, 4; October, 2, 1899, 8.

[44] Lancashire Evening Post, June 10, 1901, 6; Sporting Life, June 17, 1901, 1.

[45] Sporting Life, November 6, 1901, 2.

[46] The Era, April 29, 1899, 21; Music Hall and Theatre Review, April 4, 1902, 1; The Stage, March 2, 1905, 1.

[47] Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette, January 23, 1902, 1; Dublin Evening Telegraph, April 7, 1902, 1; Edinburgh Evening News, December 23, 1902, 2.

[48] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1911, England & Wales births 1837-2006, Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk.

[49] Kat Jungnickel, Bikes and Bloomers: Victorian Women Inventors and their Extraordinary Cycle Wear (London: Goldsmiths University of London, 2018), 121-154.

[50] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911, Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk.

[51] Sporting Life, July 6, 1892, 3; London Daily News, August 20, 1897, 3.

[52] Dick Swan, ‘Early Women Racers’, The Boneshaker, Spring 1992, No 128, 13; Kat Jungnickel, Bikes and Bloomers, 135.

[53] ‘The Chelsea Rationalists’, The Hub, July 9, 1898, 419.

[54] ‘The Chelsea Rational Cycling Club: Good Sport by Lady Riders’, Sporting Life, August 16, 1898, 4.

[55] ‘Professional Lady Cyclist’s Spill’, The Daily Telegraph, March 9, 1899, 4.

[56] ‘Lady Cyclist’s Earnings’, Reynolds’s Newspaper, March 7, 1897, 8; Kat Jungnickel, Bikes and Bloomers, 134.

[57] Gloucestershire Echo, September 11, 1909, 1.

[58] ‘Chelsea Tradesman’s Grave Injury’, Chelsea News and General Advertiser, July 31, 1914, 5; ’King’s Road Woman Incapable’, February 5, 1915, 2; ‘Jeweller’s Shop Problem’, March 24, 1916, 3. West London Press, January 16, 1914; March 10, 1916;

[59] England & Wales Deaths 1837-2007 (Battersea, London), Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk.

[60] London Evening Standard, November 29, 1895, 3.

[61] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1881, 1891, 1901, Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk

[62] ‘Sports at the Manor Ground, Plumstead’, Kentish Mercury, August 9, 1895, 6.

[63] ‘Three Years as a Lady Racer. Some Experiences of Miss Blackburn’, The Hub, March 12, 1898, 231; Penny Illustrated Paper, June 12, 1897, 10; Hampshire Advertiser, June 23, 1897, 2; Islington Gazette, May 27, 1898, 2; Six-Day Cycle Races, http://www.sixday.org.uk.

[64] Belfast News-Letter, April 4, 1899, 6.

[65] Sporting Life, May 8, 1899, 3.

[66] The Hub, March 20, 1897, 251; Dick Swan, ‘Early Women Racers’, The Boneshaker, Spring 1992, No 128, 13.

[67] Driffield Times, April 23, 1898, 4; ‘Mrs Clara Grace, The Champion Lady Rider’, Illustrated London News, November 27, 1897, 26.

[68] Belfast News-Letter, August 5, 1901, 3; Sporting Life, September 4, 1901, 7; Sporting Life, October 5, 1901, 6; Tyrone Courier, October 10, 1901, 7; Sporting Life, May 21, 1902, 1.

[69] Norfolk News, August 8, 1903, 6.

[70] England, Wales & Scotland Census 1901, 1911, Marriages and Deaths (Wandsworth, London), Findmypast, http://www.findmypast.co.uk.

![“And Then We Were Boycotted” <br> New Discoveries About the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 3](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Marco-Giani-Boycotted-Part-3-440x264.jpg)