To hear some people talk about Rodeo you would fancy it was something compounded from roots, smelling herbs and second guesses. Well, it isn’t!

Neither is it a circus nor a zoo nor a listening in séance. Its – it’s – well it’s Rodeo. And you can put the accent on the aye. Or the oh! Just according as you feel about the matter.

The Sunday Independent, 24 August 1924

-

‘Tex Austin’s Croke Park Rodeo’.

Courtesy of the Croke Park Museum and Archives, Dublin.

Tasked with relaying an entirely new form of entertainment to the Irish public in 1924, the Sunday Independent chose to explain the American style rodeo in light hearted terms. From August 17 to August 24, Croke Park, the stadium traditionally home to Gaelic Football and Hurling, welcomed Tex Austin’s rodeo extravaganza. Featuring bronco riding, trick riding, traditional rodeo clowns and even an opportunity for Irishmen to participate, Austin’s Rodeo briefly took Irish society by storm. Part of a growing fascination with American culture, Austin’s rodeo came at a pivotal moment in Irish history. Having recently achieved independence from Great Britain, southern Ireland, or the Irish Free State as it was then known, was still a nation still struggling to establish an identity. Sport and recreation came to play a pivotal role in this process and, at the very least, served as a distraction from more serious economic and political matters. In the case of Tex’s rodeo, it was used to distinguish Irish and British notions of entertainment and further strengthen America’s hold on Irish recreation.

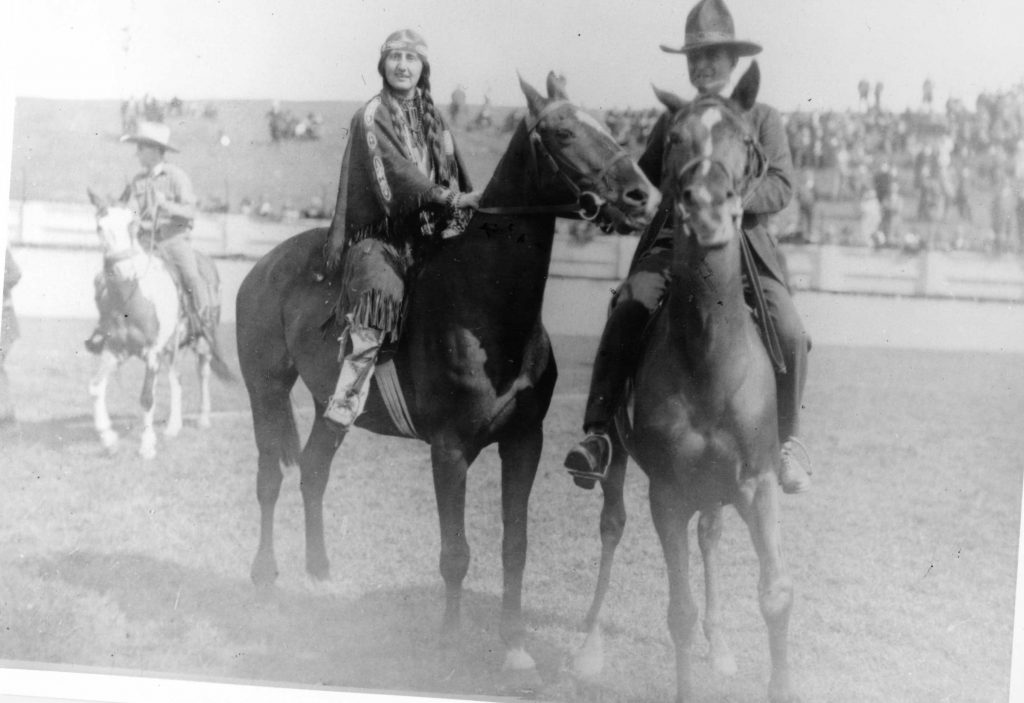

In the first instance, Austin’s rodeo came immediately after the hosting of the 1924 Tailteann Games. Later understood by Mike Cronin as an attempt to project a new Irish identity into the international realm, the Tailteann Games were described as a ‘race Olympiad’ whereby Irish athletes, and those of Irish descent, were invited to take compete in a series of events from athletics to painting. During the Games’ sporting events athletes from America, England, New Zealand and Australia competed alongside their Irish counterparts. Hugely successful, both domestically and internationally, the Games were seen to mark a new epoch in Irish history. Done, in part, to help distinguish the Irish Free State from its previous, imperial, past, the Tailteann Games marked the first major sporting cultural event of the new nation. Tex Austin’s rodeo was the next. Initially planned to take part during the Tailteann Games itself, Austin’s rodeo was eventually scheduled to take place immediately after the Games. First appearing at Wembley Stadium, where the reception to the Rodeo was mixed, Austin’s rodeo enjoyed a great fanfare when it came to Ireland. Unlike British crowds, who protested at the rodeo’s lax animal cruelty policy or those in Wembley who reportedly sat bemused at the proceedings, Irish audiences proved far more welcoming to Austin’s rodeo.

- ‘Pictorial News of the Week’, Sunday Independent, August 17, 1924, 3.

Over the course of a single week, Austin’s rodeo played two shows a day at Croke Park, one at midday and the other in the evening, to over 100,000 spectators in total. Capitalizing on the goodwill fostered by the Tailteann Games, the rodeo benefited from the Games’ still existent infrastructure. Thus, special trains remained to take people to Dublin, including trainlines running from Northern Ireland, which was still part of Great Britain, into the Irish Free State. What makes the Irish response even more spectacular is that few individuals knew what a rodeo actually was. The best the Weekly Irish Times could come up with prior to the rodeo was to state that it was ‘not a Buffalo Bill stunt’ and that the word ‘is pronounced Ro-day-o with the accent on the second syllable.’ Closer to the event, the La Scala Theatre in Dublin ran a series of short rodeo films as part of a pseudo-educational but entertaining experience. On entering Croke Park, spectators were given the option of buying a special programme with a ‘Cowboy Dictionary’ included.

The dictionary proved to be particularly useful for many involved. According to the Irish Times,

Many, before entering the grounds at all, had made a careful study of the ‘Cowboy Dictionary’ included in the official programme.

They learned that ‘crow hops’ was a term contemptuously applied to mild bucking motions and that a ‘man killer’ was a wild horse with a homicidal mania.

That so few people knew what a rodeo actually entailed was beside the point. They knew it would be entertaining and, still buoyed by the Tailteann’s spectacles, they had few qualms about attending.

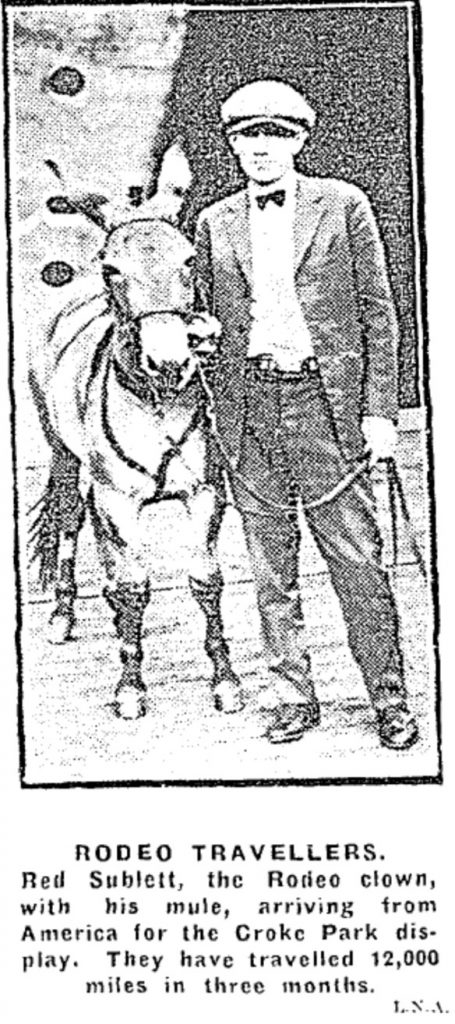

The shows themselves followed a largely set routine. Opening with ‘Red’ Sublett’s comedic performances, audiences were treated to a mixture of Irish and American performances. The Free State Army band played shows in between displays of galloping horses and bronco riding competitions. When the military band retired, they were replaced by the Dublin Metropolitan Police band, who played on during exhibitions of lassoing, trick riding, steer wrestling and calf roping. Each evening Irishmen were given the opportunity to compete in a bronco competition for a £5 prize, with roughly thirty men entering each night. That several Irishmen fractured or broke several bones when riding a ‘wicked animal’ did little to temper the enthusiasm shown.

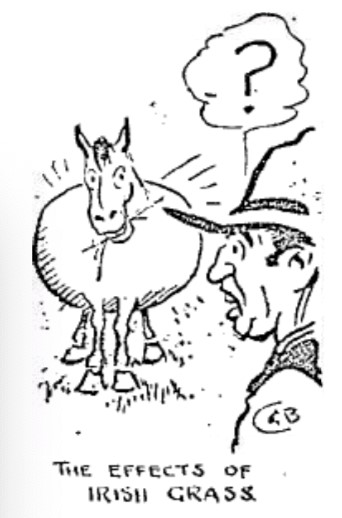

Whereas reports in British newspapers on the Wembley rodeo largely saw the event as distinctly American, and therefore not British, great efforts were made to ingratiate American and Irish cultures. On August 18, the entire day’s proceeds were donated for the benefit of the Jubilee nurses, a decision which further endeared the rodeo to Irish audiences. Other efforts included the promotion of those riders supposedly of Irish descent, such as Miss Vera McGuinness. Bonnie McCarroll and Tommy Kirnan, all of whom enjoyed a great deal of attention from the press. The strangest, but perhaps most effective approach was the inclusion of Irish horses and bulls in the rodeo itself. Reporting on a day’s proceedings, The Sunday Independent specifically cited Irish calves as a source of pride for the Irish nation. The same article went so far as to claim that Irish grass, deemed the best in the world, had even strengthened Tex’s animals. Oftentimes the enthusiasm of Irish audiences was contrasted with British fans who had, supposedly, proven immune to the rodeo’s charms.

- ‘Oh, Oh Rodeo!!’, Sunday Independent, August 24, 1924, 7.

Although faced with experienced ‘bronco busters’, the Irish calves performed admirably and even won over the crowd – ‘The crowd was always with the calves. Always. They were Irish calves.’ Given the recent national jubilation, which was the Tailteann Games, it is perhaps unsurprising to read that time was also spared to insult the rodeo’s former hosts. – ‘Ye can’t cod the Irish calves like the Wembley weaklins’. Anti-English sentiment aside, no matter how tongue in cheek it may have been, the Rodeo had been an unequivocal success. The day and evening shows had been largely sell out affairs. Official and unofficial merchandise had sold widely and, when Tex Austin’s troupe boarded the Cunard back to the United States, Irish newspapers gleefully told of their promised return in 1928.

More immediately, the rodeo’s aftermath contributed to a growing American presence in Irish leisure. By the 1930s, American film and pulp fiction led to a growing Irish fascination with cowboys and the American West. As retold by Elizabeth Russell ‘deeds of macho men suffering madcap mishaps and even triggering friendly tales of violent frontier men were all allowed to circulate’ in Ireland. The seeds for this fascination were sown, in part, by Tex Austin’s rodeo. Returning to the Sunday Independent, it was claimed that

You notice, too, another evidence of the Rodeo aftermath in our streets and public places. The newsboys and their smaller brethren have raided Fairview Park for brown paper to make sombreros; old sacks with side whiskers are converted into ‘chappies’ (cowboy language for trousers) and cast-off socks into moccasins

The Laddios of the laneways are lassoing on the highways. When it’s not guns it’s ropes. When it’s not hand up it’s hats off

Tex Austin did not return to Ireland, although he did make an ill-judged appearance in England in 1934 which resulted in a near prosecution on animal cruelty charges. Despite his absence, the rodeo and fascination with American frontier life continued in Ireland. ‘Rodeo follies’ became a regular appearance in Irish theatres, cowboy books sold widely and, if reports are to be believed, the sight of hordes of children pretending to be cowboys was a common sight in city streets. Ireland’s reliance on Anglo-American culture during the 1920s and 1930s took shape in weird and wonderful ways.

Article © Conor Heffernan

References:

British Newspaper Archives.

Cronin, Mike. “Projecting the nation through sport and culture: Ireland, Aonach Tailteann and the Irish Free State, 1924-32.” Journal of Contemporary History 38, no. 3 (2003): 395-411.

Irish Newspaper Archives.

Russell, Elizabeth, ‘Holy Crosses, Guns and Roses: Themes in Popular Reading Material’, in Joost Augusteijn (ed.), Ireland in the 1930s: New Perspectives (Dublin: Four Courts, 1999), 11–28.