Although bodybuilding has become something of an outlier sport in today’s popular culture, there was a time when the sport was placed alongside football or rugby in terms of its acceptability. Furthermore there was a time when a Prussian, and not an Austrian, was seen as the quintessential bodybuilder. Finally, and to labour the point somewhat, there was a time when Great Britain was the undisputed home of bodybuilding.

For readers struggling to remember such a time, you can rest assured in the knowledge that the period in question was over a century ago.

1901 was in many ways the height of bodybuilding’s fame in the British Isles as it was that year which saw 15,000 spectators cram into London’s Royal Albert Hall to see sixty British men line the stage in black tights and leopard skins. An undoubtedly odd sight to the impartial observer, this occasion marked the first recognizable bodybuilding contest in the modern age. An occasion to celebrate both British bodybuilding and the British Empire.

Bodybuilding and the British Empire may seem an odd combination for modern readers yet our Edwardian counterparts would have undoubtedly seen the two as inseparable.

Much of this was due to the influence of a Prussian born showman named Eugen Sandow, whom we’ll be coming back to later in the article. First however, attention will be drawn to the late nineteenth-century, a time when bodybuilding practices in England were beginning to draw great public attention.

Bodybuilding for a British Empire

Though many of the exercises and workouts are the same as their modern counterparts, bodybuilding in the late-nineteenth century was known as physical culture by the exercise enthusiasts of the day. An incredibly slippery word to define, physical culture can be generally understood as those exercises concerned with the mental and physical rejuvenation of the body. Unlike that great bastion of British sport, football, physical culture was primarily concerned with the appearance of the body as opposed to some form of competition.

Similarly unlike football, physical culture’s origins were inherently foreign. The nineteenth-century had seen British exercisers adopt a series of foreign training systems from the German gymnastic systems of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn to the Swedish system of Pehr Henrik Ling. Each system was seen to have its own relative merits which explains why by the late nineteenth-century, the fitness industry in England had grown to rather large proportions.

This growth was inexorably linked to the rise of sporting pursuits such as football, rugby, cricket and boxing in the same period. While competitive sporting practices, with perhaps the exception of rowing, had not embraced physical training in the way current athletes have, the morals and messages attached to exercise ensured that non-competitive exercise practices such as weight-lifting and gymnastics found an equally welcome reception in British circles.

- Professor Harrison in 1852

Coupled with this, the desire amongst Victorian and Edwardian consumers for new and varied types of entertainment opened the way for weightlifters and strongmen. Take ‘Professor Harrison’ for example, a mid-century Victorian strongman who spent a decade touring England with his impressive Indian Club swinging act. In Harrison’s wake came dozens of performing strongmen and at times, strongwomen. Such athletes forced new ideas about what was possible for the human body, and what could be attained through progressive weight training. While many performers capitalized on the growing English interest in physical culture, it was Eugen Sandow who helped raise this interest to near stratospheric levels.

The Face of British Bodybuilding…

While it may seem odd to label a German showman as the face of British Bodybuilding, there are several reasons why Eugen Sandow is worthy of such an accolade. Born in Königsberg, Prussia in 1867, Sandow left his home aged 18 in order to avoid military service and to etch out a career as a circus athlete. A decision, which in hindsight, no doubt shocked the sensible tendencies of his Lutheran parents.

Struggling initially to earn even a meager living at this time, Sandow travelled across central Europe in search of work. In some cities he would pose for artists seeking to depict the ideal form, while in other cities he would wrestle for weeks on end. It wasn’t until Sandow travelled to Belgium that his physical culture career was truly set in motion.

While in Brussels in the late 1880s, the young Sandow visited the gymnasium of Ludwig Durlacher, better known by his stage name of Professor Attila. Attila was, at this time, one of the best known weight lifters of the era, renowned amongst both the hoi polloi and European aristocracy for his feats of strength and endurance.

Together the two devised several plans in an effort to make Sandow a star and while a brief stint in Holland did much to raise the duo’s profile but it wasn’t until 1889 that Sandow became a man of international interest.

Sandow, Sampson and Stardom

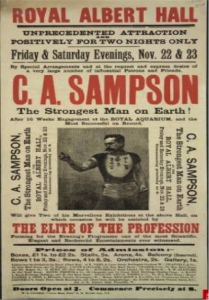

In November 1889, Sandow and Attila travelled to London in order to challenge another well known strongman of the day. The strongman in question was Charles ‘Samson’ Sampson, a crafty entertainer known for his verbose challenges. Playing at the Royal Aquarium theatre in London, Sampson had made a habit of issuing lucrative challenges to his audiences.

Keen to demonstrate his confidence, Sampson regularly wagered £500 against any opponent’s £100, that no one would be able to match his feats of strength. For many performances this appeared to be the case, until Sandow challenged the showman.

Over a series of showdowns Sandow not only proved that he was stronger than Samson, much to the latter’s annoyance, but also that he was in possession of a remarkably aesthetic figure. The publicity surrounding the pairing’s exploits had ensured a large audience for Sandow and in the wake of his victory, the Prussian began to reap the benefits of such fame.

Soon enough Sandow was touring in the United States and earning thousands of dollars for his physical culture shows. Composed of both posing and weightlifting segments, Sandow’s fame on both sides of the Atlantic helped spur a greater interest in the idea of physical culture.

This theme would continue for the remainder of the decade and by the time of the 1901 Physique Competition, Sandow boasted several works in his name, dozens of physical culture studios around England, a successful physical culture magazine enterprise and would soon have a bust of his body commissioned for the Natural History Museum.

Furthermore, the spread of weightlifting, gymnastics and the intensification of English sporting interest had ensured a healthy band of followers for the Physical Culturist’s most daring idea, a national physique show.

Preparing the Great Competition

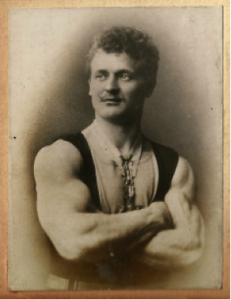

- Eugen Sandow in his youth

Much like Sandow’s own story, the Great Competition was not created overnight. In fact it was three years in the making.

As early as July 1898, the first edition of Sandow’s Physical Culture magazine spoke of upcoming physique competition to be held in Great Britain and Ireland. The then 31 year old Sandow was keen to spread the physical culture message even further across the UK and in his own words, “afford encouragement to those who are anxious to perfect their physiques.”

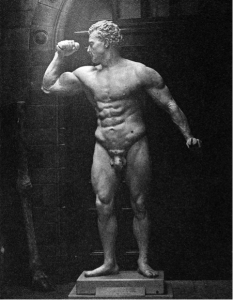

- Sandow’s 1901 Bronze Trophy

Interestingly despite Sandow’s belief that encouragement was all his competitors needed, a lucrative cash prize was offered alongside gold, silver and bronze trophies. The man who placed 1st would receive not only a gold statuette of Sandow but also a purse amounting to £500. Second place would receive a silver statuette while the third placed contestant would receive a bronze statuette.

The Application Process

Unlike his American contemporary, Bernarr MacFadden, Sandow’s physique competition was open solely to men of suitable physical standing. This meant the complete exclusion of female athletes. Such was the gender segregation of the event itself that attendance to the finale of the physique show was severely limited to female spectators, thereby imbuing the pursuit with an overtly masculine image.

That women were excluded from the event gives pause for thought. For several years Sandow had provided exercise systems for women throughout the British Empire interested in physical culture. While such systems were often of secondary importance to those provided by men, they were nevertheless provided. Similarly Sandow was a strong proponent of female physical culture in the British media and was known for chastising those who discouraged female engagement in the gymnasium.

Why then did Sandow exclude female participants? Though the Prussian, nor his biographers, have ever truly examined this point, the experiences of Bernarr MacFadden in the United States provide some clues.

- Pamhphet For MacFadden’s Physical Culture Contest

In 1903 MacFadden was the closest thing the United States had to its own homegrown Sandow. Eccentric to the extreme, MacFadden incurred the ire of American authorities when he announced that his own physical culture contest would include both men and women. By publishing photos of his female contestants in their bathing suits MacFadden was charged with spreading obscene photographs, something Sandow may have being trying to avoid.

Similarly MacFadden found a general reluctance amongst his female trainees to submit photographs of themselves for the competition. As David Chapman argued in his work on strong women, British and American audiences were not accustomed to the sight of developed female muscle. Female contestants thus ran the risk of being labeled ‘manish’ or ‘deviant’. While one can only theorize about why Sandow segregated his competition in such a manner, the experiences of MacFadden give food for thought.

For those permitted to compete in the qualifying rounds of the competition, Sandow offered regional physique contests throughout Ireland and Great Britain. Often attending the contests themselves, the winners of such shows advanced on to the ‘Great Competition’ as it was termed. Furthermore they become local celebrities in their own right. That the regional shows were seen as important by locals was evident in the fact that many newspapers proudly commented on the region’s gold medal winner. In one case, an Irishman’s obituary provided more information on his regional victory in a Sandow than it did his entire working career.

Seeking to maintain his competition’s prestige, Sandow set rigid guidelines for the ‘perfect’ male physique.

What did Sandow look for in a physique?

- 1901 Bust Of Sandow’s Physique

From the offset of the competition, Sandow’s magazine publications made it clear to both competitors and judges that prizes would not be awarded to the men with the largest physiques. Instead the following check list based on Sandow’s own ideals for the perfect physique was created. Accordingly, men would be judged on the following

- General development

- Equality or balance of development

- The condition and tone of the tissues

- General health

- Condition of the skin

Sandow’s efforts to quantify the perfect physique were by no means a new institution. As far back as the Hellenic ages, bodies were divided according to their physical dimensions. Of more relevance to Sandow’s age was the emergence of statistics in the fitness field in the 1860s.

Owing primarily to the work of Archibald MacLaren, a private gym instructor responsible for developing a regulated fitness program for the British army, Englishmen had increasingly become concerned with their physical measurements as a sign of their overall health. This anxiety would reach its apogee at the time of Sandow’s Great Competition when Britain’s recruitment drive during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) revealed the poor physical conditioning of England’s working class men.

Sandow’s measurements and competition were undoubtedly of interest to those who felt that Britain’s national physique was waning.

The Show Itself

After three years adjudicating county championships, Sandow finally announced the date for the ‘Great Competition’ for September 1901. Choosing London’s Royal Albert Hall as the venue, Sandow displayed remarkable confidence in his endeavor as the Hall boasted over 15,000 seats. That the show sold out within weeks of Sandow’s announcement proved his hubris to be well founded indeed.

- A contemporary depiction of the Royal Albert Hall

Illustrating the connection between physical culture and the British Empire, Sandow announced in the build up to the Competition that all monies raised, regardless of expenses, would be donated to the “Mansion House Transvaal War Relief Fund”, a war fund established for those soldiers fighting in the then ongoing Anglo-Boer War. For many, this act of generosity solidified Sandow’s place in the hearts of the English public and indeed it is interesting to note that seventy years after the fact, historian David Webster still referred to Sandow as a great friend to humanity for this gesture, amongst others.

Though displaying remarkable charitableness, Sandow was still, at heart, a showman, something that was demonstrated in the spectacle that was the ‘Great Competition’. The show opened at 8pm on September 14, with a somber yet rousing performance by the Irish Guards in memory of slain US president William McKinley, who had been assassinated just one week prior. The highly emotive performance brought the entire audience to its feet with reporters noting that the large American contingent in the audience that night were “unmistakably touched by the earnest and solemn demeanor of all.”

Once the music stopped, Sandow had the house lights extinguished. Bursting from the darkness came 20 powerful spotlights, illuminating the march of 50 boys from the Watford Orphan Asylum. A display that “aroused the audience to a great pitch of excitement.”

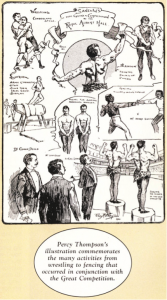

- The Great Competition featured everything from wrestling to fencing

After this came a variety of athletic displays ranging from wrestling to fencing. Nevertheless despite his audiences’ enthusiasm for the events, it became clear an hour into the show that some in the audience were anxious to see the spectators emerge from behind the curtain. It wasn’t long after that sixty British competitors marched towards the stage with ‘The March of the Athletes’, an anthem supposedly penned by Sandow himself, bellowing through the theatre.

Crowding out the stage, the men readied themselves for the judges’ inspections. Wearing black tights, jockey belts and leopard skins, the men were presented as the finest specimens in all of Great Britain and Ireland. This was reflected in the reporting the next day. One particularly enthused reporter stated that “to stand in their ranks was a distinction.”

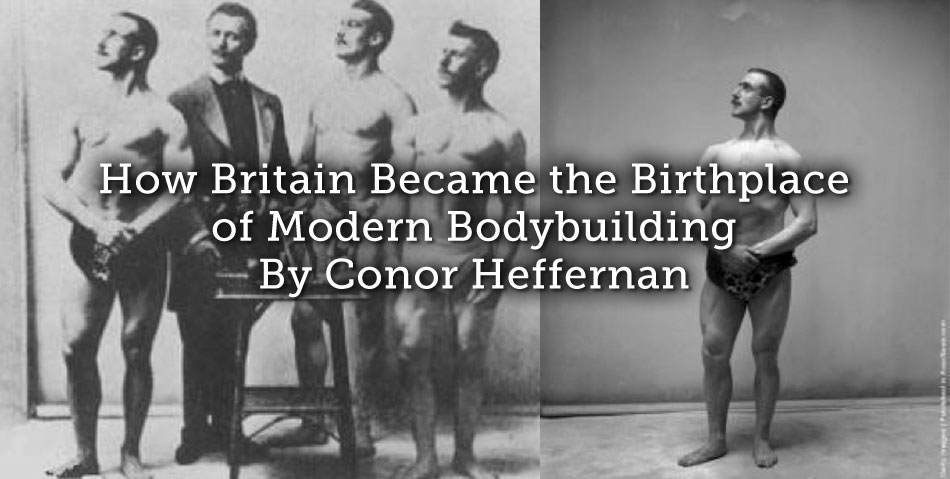

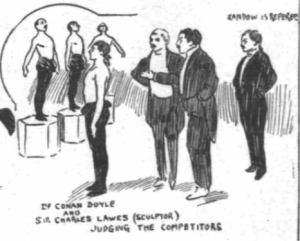

- Charles Lawes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sandow judging the contestants

The judges of the night were Sir Charles Lawes, a famous sculptor and amateur athlete and Dr. Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the Sherlock Holmes series. Prior to the event, it had been decided that should a disagreement between the two guest judges arise, Sandow would decide the winner. The fact that neither of the men had any great experience in physique competitions mattered little. Their names gave an immense credibility to the Competition.

Slowly the judges walked towards each contestant, closely examining the sinews of each man. In some cases, the judging resembled that of a dog show, as Arthur Conan Doyle was noted for his particularly attentive judging style, which saw him stoop on all fours to examine competitors. Within the hour the group of sixty men was cut to just twelve. An intermission was then called to give the judges time to reflect.

When the curtains were raised once more a 34-year-old Sandow stood on stage for the day’s last performance. Displaying his remarkable talents, Sandow tore packs of cards in two, lifted unimaginably heavy weights overhead and bounced his muscles in tune with the accompanying music. For five minutes spectators gave Sandow a standing ovation and once a silence finally returned to the hall, the Competition neared its end.

With Sandow backstage, the 12 finalists were brought back out. This time each man stood atop a pedestal and was given a set of compulsory poses. Such poses required the men to tense their muscles for minutes on end, a grueling endeavor exacerbated by the knowledge that any physical flaw would be picked up by the judges. Emulating Doyle’s previous antics, Eugen Sandow now resorted to going “on his hands and knees to examine the nether limbs of men.”

- A short sketching of the posing rounds

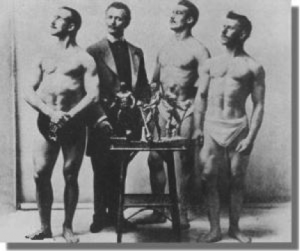

Once every competitor had finished their poses, the time came to choose the best-developed man in Great Britain and Ireland. A hush fell through the Hall as three men were brought forward. They were A.C. Smythe from Middlesex, D. Cooper from Birmingham and William Murray from Nottingham.

Having separated the trio from the remaining nine finalists, it was announced that Smythe had finished in third place. Cue applause and anticipation from the audience. The house lights dimmed as D. Cooper was announced as the second place contestant. A jubilant William Murray struggled to contain his excitement. Moments later he was honored with the title of the ‘Best Developed Man in Great Britain and Ireland’.

- Sandow with the winning contestants

Applause boomed throughout the Hall as Sandow and his golden trio disappeared from view. The morning’s papers deemed the Competition a rousing success, whose achievements they hoped would encourage more British men to engage in physical culture.

- William Murray, Circa 1901

William Murray used his new fame to etch out a successful career both on and off the stage for the next five decades, while Sandow’s star continued to rise until the outbreak of the Great War. Although ceremonial, Sandow’s appointment as Professor of Scientific and Physical Culture for King George V of England in 1911 demonstrated how highly the Prussian came to be seen within the British Empire.

Conclusion

Though the Great Competition has long faded from the British conscious, it is undeniable that this physique competition was a seminal moment in British social history. In the first instance, the Competition can be viewed as a culmination of a growing public interest in sport and health. Such an association is obvious.

Less obvious is the relationship between the Competition and the British Empire itself. Sandow’s contest came at a time when official concerns about public health had reached its zenith. The reality of the Anglo-Boer War had caused many to reflect upon how citizen’s bodies needed development. Sandow’s enterprise and system of physical culture seemingly provided a solution. Similarly that Sandow donated the proceeds from his Competition to a British soldier’s fund demonstrated how literal this connection between physical culture and Empire was for the ‘Father of Physical Culture.’

Finally the regional nature of Sandow’s opening contests demonstrated the inter-connectedness of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish concerns about physical culture. While Michael Anton Budd and Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska have done great work in highlighting the importance of physical culture to English life in the opening decades of the twentieth-century, histories of Welsh, Scottish and Irish physical culture have yet to be written. Reflecting on Sandow’s competition, it becomes clear that such histories have the potential for rich and interesting research. That counties throughout these regions held physical culture contests demonstrates the hold that physical culture such societies.

Article © Conor Heffernan