Please cite this article as:

Heffernan, C. Muscle Building and Society Bending: The Slow Birth of Irish Bodybuilding, In Day, D. (ed), Playing Pasts (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2020), 20-36.

ISBN paperback 978-1-910029-56-5

Chapter 2

______________________________________________________________

Muscle Building and Society Bending: The Slow Birth of Irish Bodybuilding

Conor Heffernan

____________________________________________________________

Abstract

In 1946 the British weightlifting and bodybuilding magazine Health and Strength included a feature on the inaugural ‘Ireland’s Best Developed Man’ competition, a bodybuilding and physique contest open to Irishmen of varying weight and muscularity. Said by the magazine to be the first bodybuilding contest of its kind in Ireland, the event featured men from across the country attired solely in posing trunks, flexing their trained and oiled muscles for the assembled audience of men, women and children. Using the 1946 contest as a seminal starting point in Irish bodybuilding, the following chapter examines why, unlike other countries, the Irish interest in physique shows occurred so late in the twentieth century. Taking both a transnational and domestic approach, the chapter seeks to understand why, unlike other countries, the Irish interest in physical culture did not manifest itself in physique shows during the period 1900 to 1939.

Keywords: Ireland, Bodybuilding, Physical Culture, Masculinity, Twentieth Century

Introduction

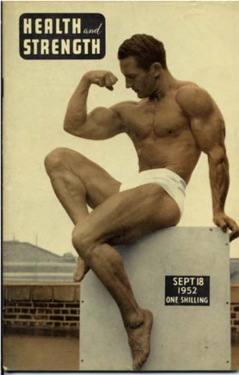

Twelve contestants stood on stage in December 1946 seeking the title of ‘Ireland’s Best Developed Man’. Gathered in St. Mary’s Hall, Belfast, the aspiring bodybuilders and physical culturists ran through their mandatory poses, hoping to impress judge and spectator alike. Done alongside weightlifting and gymnastic competitions, the bodybuilding show was gleefully reported on by Health and Strength magazine the following week.[1] Produced in London, but read in Ireland, Health and Strength was one of the twentieth century’s most popular outlets for British and Irish health enthusiasts. Founded in 1898, the magazine covered everything from yoga to correct diet.[2] Its unnamed reporter, relaying the events from Belfast, spoke of glistening bodies flexing and straining on stage. As the men ran through their poses, their numbers were lessened. First to seven and then, in time, to one. Belfast born Mervyn Cotter, a man known for both his weightlifting prowess and impressive physique, was declared Ireland’s ‘Best Developed Man’ in the competition’s inaugural year.

Concluding their report, the correspondent claimed that ‘so ended the first physique contest to be held in Ireland, and according to results it will not be the last but a forerunner of a series of yearly contests’.[3] This statement, seemingly innocuous at first, was only partially correct. Many competitions were indeed held after the inaugural show and continued almost unbroken, to the current day.[4] This was not, however, the first time that Irishmen had competed in such a manner. Four decades previously, Irishmen had donned posing trunks, taken photographs, and competed in Eugen Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’ of 1901. Done to determine the best developed man in Ireland and Great Britain, Sandow’s competition, and Sandow’s subsequent magazine competitions, have been seen by several scholars as the first modern physique contests of their kind and a precursor to the sport of bodybuilding.[5] That Health and Strength, a magazine founded in 1898, neglected to mention Sandow’s shows, or their imitators within the Irish context gives pause for thought.

From 1908 to 1946, no official physique competitions took place in southern Ireland. In Northern Ireland, which was partitioned from southern Ireland as part of Great Britain in 1920, Irishmen continued to compete in magazines and live competitions. At a time when physical culture competitions and bodybuilding shows emerged in Great Britain, Italy, France, Germany and the United States, southern Ireland appeared almost entirely disinterested.[6] The reasons behind the south’s relative lethargy toward bodybuilding in the opening decade of the twentieth century form the basis of the present chapter. Surveying roughly three decades of Irish history, the chapter argues that southern Ireland’s political and economic turmoil, combined with a socially conservative public sphere, delayed the emergence of bodybuilding at a time when the sport’s popularity grew elsewhere. Bodybuilding, as a pursuit, is a niche and, at times, subversive pursuit. Its slow growth in southern Ireland nevertheless spoke of much broader societal, economic and political problems plaguing the state.

The beginning of Irish bodybuilding

Figure 1. Mervyn Cotter, 1952

It is within this context that Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’ must be placed. Announced in late 1898, Sandow’s competition was not concerned with finding the greatest muscular bulk but rather with the discovery of a man brimming with vitality. Overall musculature was combined with nebulous ideas like vim and vigour, said to be observable through the health of one’s skin, posture, demeanour and so on.[12] Sandow’s contest, unlike its later bodybuilding equivalents, was concerned with contestant’s overall health. To enter Sandow’s competition, competitors were required to take photographs of themselves and submit them alongside coupons available through Sandow’s magazine.[13] Photographs were then evaluated by Sandow and his fellow adjudicators in London. The top three contestants from each county were awarded a gold, silver or bronze medal respectively, with the top entrant invited to compete in Sandow’s finale at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 1901.In 1898, readers of Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture were met with an exciting and unprecedented announcement. Eugen Sandow, the man many deemed to be the world’s most perfectly developed man, was hosting a physical culture competition to determine the best developed man in Great Britain and Ireland.[7] By this point, Sandow had spent roughly a decade in the public limelight, courting worldwide attention from reporters, physicians, politicians and even monarchs.[8] He was, according to his respective biographers, David Chapman and David Waller, the undisputed ‘face’ of the physical culture movement.[9] Defined by Michael Anton Budd as a late nineteenth and early twentieth century concern with the ideological and commercial cultivation of the body, physical culture, as a pursuit, took hold of the British, and by extension her Empire’s, consciousness at this time.[10] Weightlifting and, at times, competitive sport, was labelled as physical culture by many as a catch all term during the early 1900s but in the broader British lexicon, the term was applied primarily to the building of the body for the body’s own sake.[11]

Upon the announcement of the competition, Ed Boyne, a young barber from Dublin, submitted his photograph for consideration.[14] He was followed by countless other Irishmen. Writing in late 1899, Sandow explained that

In Dublin and Belfast, the competitors if not quite so numerous as in their big English centres, were in an equally forward state of physical development. Schools are about to be opened in the other large cities of the Emerald Isle and if we can take what we saw in Dublin and Belfast as a standard, Ireland will rank with the foremost nations of the world for the physical development of her sons…[15]

By 1901, Sandow’s Irish contestants included Roman Catholic Farmers, Church of Ireland Smiths, Church of Ireland Railway Officials and a Protestant Furrier. Class, creed and location varied and differed immensely.[16] Owing to a combination of travel logistics, ill luck and, in one case, a very serious illness, no Irishmen attended Sandow’s London finale.[17] A precedent had, however, been set. Irishmen had competed in a physique competition. Furthermore, they had done so in a largely respectable way. Margaret Walter’s claim that the male nude largely disappeared during the nineteenth century has, in recent years, undergone great historical criticism.[18] Sandow’s competition nevertheless had the potential to be seen as lewd and subversive by outside spectators.[19] It was, according to Michael Anton Budd, only through Sandow’s keen eye for respectability and promotion that the competition was viewed as acceptable and even, in some quarters, as scientific.[20]

In the wake of Sandow’s ‘Great Competition’, the strongman held several additional physical culture competitions through his magazine. Irishmen thus entered Sandow’s ‘Empire Competition’ and, even, his ‘Best Developed Baby’ competition, the latter of which was won by six-month-old William Bobs Whitmore from Dublin, in 1906.[21] Important though it was, Sandow’s competition was not the only physique-based outlet for Irishmen. In 1908 a ‘Physical Development’ competition was held in Dublin’s Empire Palace Theatre. Advertisements for the ‘Amateur Athletic Tournament’ began in Irish newspaper in March 1908 with 6 April ultimately chosen as the date for the live event.[22] The event provided an indication that the physique associational cultures found in England, had come to Ireland.

Thus far, it has proven impossible to discover how many men entered the contest. That advertisements produced in the lead up to the event noted ‘enormous numbers of entries from all parts’ suggests that it was well attended.[23] Many of the contestants took part in several of the events, including the eventual winner of the physical development contest, W.N. Kerr, who competed in the wrestling contests. Two years previously Kerr told the English physical culture periodical, Vitality magazine, that while ‘I cannot boast of very large muscles yet’, he had begun his interest in physical culture.[24] By 1908, he had bested several others in Ireland’s first recognisable bodybuilding show. Kerr’s bodybuilding title went unchallenged until 1946 when physique competitions emerged once more for the whole of Ireland. In Northern Ireland from 1918 to 1939 men continued to submit photographs to numerous physique competitions often held on a monthly basis in British bodybuilding periodicals.[25] Southern Irishmen, on the other hand, were almost entirely absent from such shows. Similarly, no physique competitions took place in southern Ireland from the outbreak of the Great War until the late 1930s. The absence of southern Irishmen from such competitions and the ‘slow birth’ of Irish bodybuilding was predicated on warfare, social conservatism and economic downturns.

Figure. 2. W.N. Kerr, c. 1908.

Physical culture and the decade of revolution

Michael Anton Budd and James Campbell have both remarked upon the impact the Great War had on systems of physical culture.[26] For Campbell, the realities of warfare forced changes in military physical culture, whose effects were keenly felt in the following decade.[27] Budd, on the other hand, examined the manner in which the Great War exposed many of the frailties underlying recreational physical culture.[28] Indiscriminate loss of life, material shortages and deprivation were contrasted with older conceptions of Edwardian physical culture. Put simply, it was impossible to celebrate the body at a time when soldier mortality was staggeringly high. The War was also said to have materially impacted physical culturists. More than one physical culturist, including the great Eugen Sandow, went bankrupt during the conflict.[29] Several physical culture periodicals were forced to close and those that remained open struggled to meet print runs. Health and Strength was one of the few periodicals to remain in operation but its shortened content, oftentimes totalling just four pages, paled in comparison with the previous decade.[30] Printing on cheap pulp paper, the magazine became a jingoistic mouthpiece for the war effort. That no physique competitions were held during this time, in print or in person, was telling of the War’s impact in civilian life.

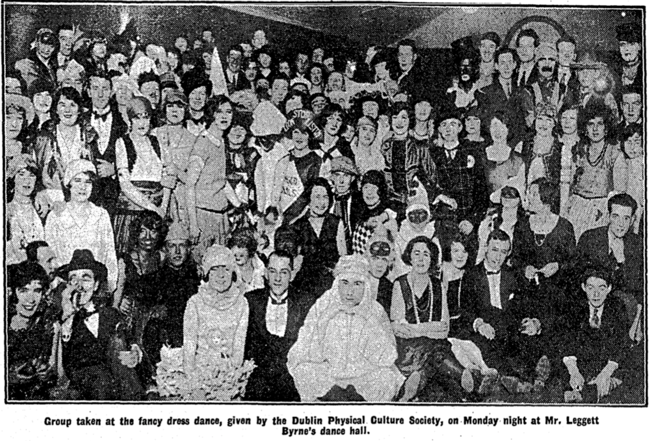

In Ireland, the outbreak of war had two effects. First it negatively impacted recreational outlets for physical culture by restricting the number of physical culture periodicals available in the country.[31] The financial strains imposed by war resulted in the closure of several large-scale gymnasia, many of which remained closed for the remainder of the decade. The Dublin Physical Culture Society, which boasted several hundred members in 1914, was forced to close sometime the following year, only to reopen again in the mid-1920s.[32]

War also affected the main audience for physical culture, namely young men with disposable income. The displacement of men from Ireland was smaller than France or England but its impact was nevertheless important.[33] David Fitzpatrick previously estimated that roughly 200,000 Irishmen enlisted, a figure that represented roughly ten percent of the adult male population in Ireland.[34] This ten percent was, however, primarily composed of men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five, the prime physical culture demographic.

Figure 3. Dublin Physical Culture Society, c. 1928. .[35]

Where does physical culture and bodybuilding fit into this history? The move towards nationalist warfare in Ireland, in both 1916 and subsequently 1919, was, in part, fuelled by physical culture practices. Prior to 1916, several of the leading members of the Rising used physical culture, either personally or as a means of strengthening bodies with an eye to political freedom.[37] Patrick Pearse, an Irish cultural nationalist, insisted that the physical culture taught at his school, St. Enda’s Rathfarnham, was combined with a nationalist ethos.[38] Pearse’s efforts to combine physical culture and nationalism was echoed by Na Fianna Éireann, a nationalist equivalent to Lord Baden-Powell’s Boy Scouts. Led by later members of the 1916 Rising, recollections from Na Fianna stressed the importance of exercise as a political project. This was not a trivial point.[39] During the Irish War of Independence, the IRA actively recruited physical culture instructors to train men in physical drill. This was the case for Thomas Halpin, drilled by ‘Old Horse’, Joe O’Neill. As a brother-in-law of an IRA officer, O’Neill was co-opted into training IRA recruits before the RIC persuaded him to cease.[40]

The IRA’s keen interest in physical culture for political, as opposed to aesthetic, reasons soon paid dividends in battle. Diarmaid Ferriter previously highlighted the nationalist’s reputation among British officers for its corps of physically fit and strong troops. Ferriter has also stressed the importance of physical fitness to the war effort, noting the vast distances guerrilla fighters travelled to engage with British combatants.[41] Individual soldiers, like Tom Barry, Geoffrey Ibberson and Maurice Donegan, later spoke of the importance physical culture played in their ability to continue fighting.[42] Physical culture and an interest in the body did not disappear during the ‘decade of revolution’, in fact it was arguably heightened. What had changed, dramatically, was its emphasis.

From 1914, physical culture in Ireland became increasingly politicised. Whereas pre-war physical culture was, with the exception of the military, largely divorced from political appropriations, the ‘decade of revolution’ saw a noticeable shift from recreational to politicised exercise. In the lead up to the 1916 Rising, Irishmen, and, to a lesser extent, Irish women, were prepared for battle through the use of physical culture exercises.[43] When the Great War ended in 1918, Irishmen returning home from battle were actively recruited by Irish and British forces to take part in an upcoming conflict. Once more physical culture systems of exercise came to play a role in preparations.[44] Warfare directed men’s attentions away from recreational physical culture during an already tumultuous period. In England in 1919, Health and Strength and other periodicals began to resume their physique contests as gymnasiums re-opened around the country.[45] Indeed, Anna Cardon-Coyne has found that the return of injured soldiers in 1918 and 1919 precipitated a resurgence of interest in the body.[46] This was not the case in Ireland where the outbreak of the War of Independence (1919-1921) diverted men’s attentions away from the recreational physical culture that underpinned bodybuilding competitions.

For those uninterested in revolt, this turn in physical culture was hard to escape. Commenting on the stagnation of Irish physical culture in the mid-1920s, J. Maxwell Neilly, a physical culture writer of the pre-war period, cited the large rate at which gymnasiums closed during the War of Independence.[47] Neilly complained that the destruction wrought by guerrilla warfare, combined with a loss of members, forced innumerable men and women to exercise without a gymnasium or instructor. Further exacerbating matters was a subsequent Civil War in southern Ireland from 1923 to 1924, which intensified these closures. In his pre-war journalism, under the nom de plumb of ‘Huck Finn’, Neilly was one of Ireland’s most enthusiastic physical culture proponents.[48] Further evidence can be found in Health and Strength magazine. In 1923, in the midst of the Civil War, one unnamed correspondent wrote of Dublin’s dangerous environment, which he believed discouraged physical activity.

To me Dublin, on Saturday night and for days before, was as a city where dire trouble was openly, blatantly courted, guns were terrible in their plenitude…[49]

Three decades later, Leo Bowes, an Irish strongman, dedicated a series of articles in his ‘Irish Notes’ section in Health and Strength on the Civil War’s impact on Irish gymnasiums. His readers soon reached out with their own stories, as was the case with J.J. Collier in 1951.

Old time Dublin physical culturist and cyclist, J.J. Collier is anxious to contact ex members of the now defunct Dublin Colossus PC Club. Flourishing in the days of Sandow, the club was obliged to close its shutters when civil war ravaged the Emerald Isle around 1921-1922…[50]

This situation echoed broader sporting pursuits, like the GAA. As explained by Paul Rouse, the GAA, although still popular, struggled to attract the same attention from Irishmen during this period.[51] Whereas southern Irish physical culture was greatly impacted by conflict and warfare, northern physical culturists were given far more freedom to indulge their interest in bodybuilding. From the mid-1920s images of Northern Irishmen began appearing in the monthly physique competitions held in English periodicals like Health and Strength or Superman.[52] These magazines, which at times lamented the absence of southern Irishmen, provided a sustained outlet for those in the North to resume their interest in physique competitions.[53] In southern Ireland, the continued conflict diverted men’s attentions away from physical culture towards more politicised forms of exercise. Furthermore, it forced gym closures for those who interest in exercise was already being tested.

Physical culture in a conservative state

Warfare was not the only factor that limited physical culture in the Irish Free State that emerged in southern Ireland post-1923. Just, if not more important, was the socially restrictive atmosphere that accompanied independence. Senia Pašeta previously highlighted the socially and politically conservative world that was the Irish Free State.[54] This conservatism was, in part, a continuation of previous censorship trends found at the beginning of the century.[55] What differed post-independence, was that Ireland’s first government, in the guise of Cumann na nGaedhael, took a much more prominent position in the wider society. Traditionally Cumann’s conservative nature has been studied with reference to the government’s, at times draconian, efforts to make the new nation state economically viable.[56] The government’s social conservatism was equally important. Indeed, for physical culturists, the introduction of the Censorship of Publications Act of 1929 had great ramifications for their access to information.

In 1931, and subsequently in 1933 when Fianna Fáil came to power, a series of physical culture magazines were officially censored owing to policies enacted under Cumann na nGaedheal.[57] Critically these included previously accessible and popular periodicals like Health and Strength or Health and Efficiency. Some, like Bernarr MacFadden’s True Crime and physical culture periodicals were censured in several states.[58] Unfortunately, the minutes surrounding the decision to ban physical culture magazines in Ireland no longer exist. That the decision was taken at all was nevertheless illustrative of the problems facing southern Irish bodybuilders seeking information about their pursuit.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century witnessed the emergence of several dozen physical culture periodicals in Ireland from England, France and the United States.[59] While the popularity of these periodicals was negatively impacted by the conflict previously examined, their pre-war popularity was undeniable. Men submitted photographs of themselves to Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture on a regular basis, Irish newspapers modelled their own physical culture columns on foreign counterparts while foreign periodicals devoted space for Irish affairs. The content of these magazines did not appear to differ greatly in the 1930s than the 1900s except for one noticeable exception. As detailed by Michael Hau in his work on German physical culture, the interwar period saw nudism emerge as a sustained interest in physical culture periodicals.[60] The same was true for British periodicals, including Health and Strength.[61] Articles promoting nudism, and a general comfort with naked bodies, may have influenced the censorship of these periodicals in southern Ireland. It is notable in this regard that the sole Irish contribution on nudism to these magazines during the 1930s was from Bob Tisdall, an Irish Olympian runner who spent the majority of his time outside of Ireland.[62]

Whatever the reasons behind the censorship decisions, the removal of physical culture and bodybuilding periodicals hampered southern Irish bodybuilding interests. In England, a Mr. Britain contest was promoted by Health and Strength in 1930 following a series of regional contests during the 1920s.[63] In Europe and the United States a series of bodybuilding competitions were created during this period.[64] These shows, often promoted and sustained by physical culture magazines, offered a platform to compete in physique competitions. At a time when these contests grew in popularity, southern Irishmen were denied even the most rudimentary forms of platforms in the guise of periodicals. Where the decade of conflict resulted in a series of gym closures, the 1930s saw censorship take hold. These restrictions were exacerbated by the economic problems plaguing southern Ireland.

Economic wars and makeshift equipment

Cumann na nGaedhael’s tenure in office from 1923 to 1932 was characterised by the party’s staunch efforts to avoid excess spending and balancing of the budget. For many, the government’s commitment to balancing Ireland’s budget was most forcefully demonstrated in 1924 when the old age pension was lowered from ten shillings to nine. Supporting the decision in Ireland’s national chamber, one member earnestly claimed that ‘some may have to die in this country and die of starvation’ lest Ireland lose her financial stability.[65] These measures, although arguably successful in achieving the government’s aims, bred ill will among the populace. Matters worsened after 1929 when a global depression set across much of Europe and the United States. Southern Ireland was arguably better equipped to deal with an economic downturn owing to the government’s policy, but the economy still suffered.[66]

Despite Cumann na nGaedhael’s adherence to budget balancing, the party believed in free trade. In contrast, and preaching a gospel of autarky alongside promises of increased social spending, Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932 as part of a coalition government. Once in power the party methodically undertake its economic programme.[67] The party’s policies included the initiation of a tariff war with Great Britain. In a deliberately provocative act, the Fianna Fáil government withheld the repayment of land annuities to Britain.[68] These repayments dated from the late nineteenth century when Irish tenant farmers were given loans to purchase land in Ireland by the British government.

In response to Fianna Fáil’s decision, and exacerbated by the Irish government’s increasingly belligerent efforts to increase Irish independence, a series of British governments during the 1930s enacted trade restrictions against Irish goods. In response, the Irish government raised tariffs on British goods, including British iron and steel.[69] While much more work needs to be done on the impact of the ‘Economic War’ on Irish life away from farming and international relations, there is evidence it effected recreational pastimes.[70] Physical culture equipment, as typified by dumbbells, barbells or chest expanders was made from iron and steel. From the late nineteenth century, most of the physical culture equipment circulating in Ireland came from Britain.[71] The decision to inadvertently increase the cost of bodybuilding equipment proved problematic for Irish weightlifters.

This misfortune manifested itself in a rather obvious way. It restricted the kind of equipment available in southern Ireland. In Northern Ireland, where access to British goods was largely unaffected, reports on weightlifting regularly discussed barbell sets weighing in excess of 200 pounds.[72] Likewise, heavy dumbbells appear to have been common in many Northern gymnasiums. In southern Ireland, newspaper reports discussing popular physical culture were characterized by their commentary on light dumbbells or light barbells.[73] Where Northern newspapers featured a plethora of advertisements for English produced gym sets, the south’s newspapers were noticeably silent. A reason for this was undoubtedly the trade war, which resulted in higher prices for British products.

When a dedicated weightlifting club came to southern Ireland in 1935, in ‘Hercules gymnasium’, members struggled to provide the same kind of equipment and weights as their Northern counterparts. This was made clear by one member, Eddie O’Regan, who joined the club in 1937 and later recalled the club’s initial difficulties in securing the requisite equipment.

I joined the club…and came three nights a week to work out…The premises were primitive…but what it lacked in fittings it made up in enthusiasm, particularly among the few devoted founder-members who had built the whole thing themselves from nothing. They had scraped and scrounged the few bits and pieces together practically out of thin air. Considering most of them were unemployed…it was a remarkable achievement…[74]

It would take at least another decade before recognizable gym equipment came to the south at affordable prices.[75] Aside then from the overall decrease in purchasing power among Irish citizens in the 1930s owing to the global downturn and economic war, enthusiastic Irishmen in the south did not appear to have access to the same equipment as their northern or English counterparts. The south’s unique social, political and economic history coalesced to inadvertently deprive those with an interest in bodybuilding of the platform, equipment and environment for the sport.

Conclusion

In late 1939, a ‘Keep Fit Crusade’ from Dublin announced its intention to host a ‘Dublin’s Perfect Man’ competition. Advertised several weeks prior to its finale, the competition, at first glance, appeared to mark a move towards some form of bodybuilding. Reality proved otherwise. Hampered by a string of delays and postponements, the Committee stressed that the contest was not a physique competition but one exploring every aspect of Irish masculinity from personality to occupation. Budding Irish bodybuilders needed to wait another seven years for a recognized contest.[76]

How and why did bodybuilding become possible? There appear to be three answers. First, a series of weightlifting competitions emerged between southern and Northern Irish weightlifting clubs in the mid-1930s.[77] Opportunities to meet and socialise with men from other clubs and regions strengthened cross boarder collaborations. It was for this reason that the contestants for the previously mentioned 1946 contest came exclusively from weightlifting clubs which had competed against one another from 1935.[78] Second and although not officially stated, censorship on British bodybuilding magazines in southern Ireland appears to have lessened prior to the Second World War. Southern Irishmen’s submissions to these magazines increased from 1938 and became a regular occurrence in the next several decades.[79] Hercules member, Eddie O’Regan, later recalled the enthusiasm with which Health and Strength magazine was passed around the Dublin club in the late 1930s.[80] Aside from providing inspiration, the magazine gave Irishmen a long-denied platform to display the body beautiful. Finally, the intensification of bodybuilding in Britain in the early 1940s, as promoted by Health and Strength magazine, appears to have provided some form of incentive for Irish bodybuilders to hold a contest of their own.[81]

For those in Northern Ireland, bodybuilding and physique competitions had been a long established, albeit niche, form of sport. Temporarily dipping in popularity during the Great War, the 1920s and 1930s saw dozens of Northern Irishmen submit photographs to British physical culture journals as part of their regular physique contests. Southern Irishmen, on the other hand, were virtually absent from bodybuilding contests during the 1920s and 1930s. Owing to a series of social, political and economic barriers, bodybuilding, as a sport, was simply not possible. In the past Irish historians have examined the barriers to sport in individual Irish regions.[82] Bodybuilding, as a sport, is admittedly a far more niche than soccer, rugby or the GAA. Its slow growth in Ireland nevertheless spoke once more of the importance of place and space in one’s ability to engage in physical activity.

References

[1] ‘Ireland’s Best Developed Man’, Health and Strength, December (1946): 495, 500.

[2] John D. Fair, Mr. America: The Tragic History of a Bodybuilding Icon (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015), 22-23.

[3] ‘Ireland’s Best Developed Man’, Health and Strength: 500.

[4] See for example, ‘Weightlifting Championships in Tralee’, Kerryman, April 4, 1959, 3; ‘Mansion House Muscles’, Irish Press, June 14, 1969, 8. ‘Bodybuilder par Excellence – at 71!’, Kerryman, August 30, 1974, 12; ‘Can Ya Put the Boot In?’, Evening Herald, September 14, 1984, 27; ‘Galway Bodybuilders Savour National Success’, City Tribune, November 6, 1998, 4; ‘TG4’s Giant Bodybuilder’, Connacht Tribune, November 21, 2008, 4; ‘Belfast Pumped to Win Bodybuilding Championships’, May 29, 2014, 24.

[5] David L. Chapman, Sandow the Magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the Beginnings of Bodybuilding (Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 129; Dimitris Liokaftos, A Genealogy of Male Bodybuilding: From Classical to Freaky (London: Taylor & Francis, 2017), 49.

[6] David Webster, Barbells and Beefcake: An Illustrated History of Bodybuilding (Irving: Author, 1979), 1-25.

[7] Chapman, Sandow the Magnificent, 1-22 deals with Sandow’s importance at this time.

[8] Ibid. See also David Waller, The Perfect Man: The Muscular Life and Times of Eugen Sandow, Victorian Strongman (London: Victorian Secrets, 2011), 1-30.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Michael Anton Budd, The Sculpture Machine: Physical Culture and Body Politics in the Age of Empire (New York: NYU Press, 1997), 152.

[11] Thomas E. Murray, ‘The Language of Bodybuilding’, American Speech, 59, no. 3 (1984): 195–206.

[12] ‘The Great Competition’, Sandow’s Magazine, 1 (1898): 79.

[13] Ibid.

[14] ’Some Entrants from the Competition’, Sandow’s Magazine, 1, no. 6 (1898): 447; 1901 Census of Ireland, Dublin, North Dock, House 2.1 in Upper Tyrone Street.

[15] ‘The Great Competition’, Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, 3.1 (1899): 375-384.

[16] Conor Heffernan, ‘The Irish Sandow School: Physical Culture Competitions in fin-de-siècle Ireland’, Irish Studies Review (2019): 1-20.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Margaret Walters, The Nude Male: A New Perspective (London: Paddington Press, 1978), 228; Anthea Callen, ‘Doubles and Desire: Anatomies of Masculinity in the Later Nineteenth Century’, Art History, 26, no. 5 (2003): 669.

[19] Fae Brauer, ‘Virilizing and Valorizing Homoeroticism: Eugen Sandow’s Queering of Body Cultures Before and After the Wilde Trials’, Visual Culture in Britain 18, no. 1 (2017): 35-67.

[20] Budd, The Sculpture Machine, 108.

[21] Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture, Vol. VIII, January to June (1902) (London: Harrison & Sons, 1902), 67-68.

[22] ‘Amateur Athletic Tournament’, Freeman’s Journal, March 28, 1908, 6; ‘Amateur Athletic Tournament’, Evening Herald, April 6,1908, 4.

[23] ‘Amateur Athletic Tournament’, Evening Herald, April 6, 1908, 4.

[24] W.N. Kerr, ‘Letter from Dublin’, Vitality, 9, no. 1 (1906): 19-20.

[25] See for example, ‘Ireland Stepping Forward – League Gala and Carnival Successes’, Health and Strength, 41, no. 7 (1927): 180; ‘Offer to Belfast Paladins’, The Superman, 4, no. 6 (1933): 290; ‘Superman Course Competition’, The Superman, January (1933): 47.

[26] Budd, The Sculpture Machine, 110-114; James D. Campbell, ‘The Army Isn’t All Work’: Physical Culture and the Evolution of the British Army, 1860–1920 (London: Routledge, 2016), 145-192.

[27] Campbell, ‘The Army Isn’t All Work’, 193-211.

[28] Budd, The Sculpture Machine, 110-114.

[29] Chapman, Sandow the Magnificent, 170, Budd, The Sculpture Machine, 110-114.

[30] Ana Carden-Coyne, Reconstructing the Body: Classicism, Modernism, and the First World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 169-200.

[31] The impact of war is reiterated in ‘Trekking Homewards’, Health and Strength, 24, no. 17 (1919): 248.

[32] J.M.N., ‘Irish Girl Gymnasts’, Weekly Irish Times, October 27, 1923, 10.

[33] Jay M. Winter, ‘Britain’s Lost Generation of the First World War’, Population Studies, 31, no. 3 (1977): 449-466; Leonard V. Smith, The Embattled Self: French Soldiers’ Testimony of the Great War (New York: Cornell University Press, 2014.

[34] David Fitzpatrick, ‘Militarism in Ireland, 1900-1922,’ in A Military History of Ireland, ed. Thomas Bartlett and Keith Jeffrey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 388.

[35] ‘Group Photo of Dublin Physical Culture Society’, The Irish Times, January 25, 1928, 9.

[36] Diarmaid Ferriter, A Nation and Not a Rabble: The Irish Revolution 1913-1923 (London: Abrams, 2017).

[37] Pádraic Pearse, To the Boys of Ireland in Political Writings and Speeches (Dublin: Phoenix, 1924), 114; Honor O’Brolchain, Joseph Plunkett: 16 Lives (Dublin: O’Brien, 2012), 46.

[38] Elaine Sisson, Pearse’s Patriots: St Enda’s and the Cult of Boyhood (Cork: Cork University Press, 2004), 115-130.

[39] Marnie Hay, ‘An Irish Nationalist Adolescence: Na Fianna Éireann, 1909–1923’, in Adolescence in Modern Irish History, eds. Susannah Riordan and Catherine Cox (London: Palgrave, 2015), 103-128.

[40] Bureau of Military History Witness Statement 742 (Thomas Halpin, Cork), 24-25. Available at: http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie. Henceforth BMH WS.

[41] Diarmaid Ferriter, The Transformation of Ireland, 1900-2000 (London: Gardners Books, 2005), 144.

[42] Tom Barry, Guerrilla Days in Ireland: A First-hand Account of the Black and Tan War (1919-1921) (New York: Devin-Adair Company, 1956), pp. 16-20; BMH WS 1307 (Geoffrey Ibberson, Mayo), 3; BMH WS 639 (Maurice Donegan, Cork), 4.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Paul Taylor, Heroes or Traitors? Experiences of Southern Irish Soldiers Returning from the Great War 1919-1939 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015), 19-74.

[45] See for example ‘League Notes & News’, Health and Strength, 30, no. 17 (1922): 252.

[46] Carden-Coyne, Reconstructing the Body, 165-180.

[47] J.M. Neilly, ‘Sport in Ireland To-Day: Dublin Gymnasts and the Tailteann’, Health and Strength, 31, no. 14 (1922): 21.

[48] ‘The Late Mr. J. M. Neilly’, The Irish Times, January 30, 1924, 7.

[49] ‘A Dublin Nightmare: Why Siki and McTigue Defied Rebels’, Health and Strength, 32, no. 13 (1923): 99.

[50] Leo Bowes, ‘Gossip from the Emerald Isle’, Health and Strength, 80, no. 19 (1951): 46.

[51] Paul Rouse, ‘The Triumph of Play’, in The GAA and Revolution in Ireland 1913- 1923, ed. Gearoid Ó Tuathaigh (Cork: Collinspress, 2015), 33-36

[52] See Thomas McMullar, ‘Among the Ulster Gymnasts’, Health and Strength, 31, no. 23 (1922): 360; ‘Ireland Stepping Forward – League Gala and Carnival Successes’, Health and Strength, 41, no. 7 (1927): 180; ‘Offer to Belfast Paladins’, The Superman, 4, no. 6 (1933), 290; P. Kelly, ‘Irish Ideas’, The Superman, 7, no. 2 (1936), 71.

[53] ‘A Dublin Nightmare’.

[54] Senia Pašeta, ‘Censorship and its Critics in the Irish Free State 1922-1932, Past & Present, 181 (2003): 193-218.

[55] Kevin Rafter, ‘Evil Literature: Banning the News of the World in Ireland’, Media History, 19, no. 4 (2013): 408-420.

[56] Jason Knirck, Afterimage of the Revolution: Cumann na nGaedheal and Irish Politics, 1922–1932 (Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Pres, 2014), 1-22.

[57] Irish Censorship Board, Censorship of Publications Acts, 1929 to 1967, Register of Prohibited Publications (Dublin: Stationery Office, 1946).

[58] William H. Taft, ‘Bernarr MacFadden: One of a Kind’, Journalism Quarterly, 45, no. 4 (1968): 627-633.

[59] Heffernan, ‘The Irish Sandow School’.

[60] Michael Hau, The Cult of Health and Beauty in Germany: A Social History, 1890-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 3-16.

[61] Annebella Pollen, ‘Utopian Bodies and Anti-Fashion Futures: The Dress Theories and Practices of English Interwar Nudists’, Utopian Studies, 28, no. 3 (2018): 451-481.

[62] Neville Buckley, ‘Science of Nakedness: Nudist or Sunbather?’, The Superman, 3, no. 5 (1933): 21-22.

[63] John D. Fair, ‘Oscar Heidenstam, The Mr Universe Contest, and the Amateur Ideal in British Bodybuilding’, Twentieth Century British History, 17, no. 3 (2006): 396–423.

[64] Fair, Mr. America, 12-20.

[65] Fred Powell, The Political Economy of the Irish Welfare State: Church, State and Capital (Bristol: Policy Press, 2017), 84-86.

[66] ‘Extracts from a Memorandum by the Department of External Affairs on the Effects of the Economic Depression on the Irish Free State’, Department of Foreign Affairs (National Library of Ireland, No. 574, DFA 7/55).

[67] Ferriter, The Transformation of Ireland 1900-2000, 363-370.

[68] Ibid., 358-372.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Paul Rouse, Sport and Ireland: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 296-300.

[71] Conor Heffernan, ‘Strength Peddlers: Eddie O’Callaghan and the Selling of Irish Strength’, Sport in History, 38, no. 1 (2018): 23-45.

[72] See ‘Ireland Stepping Forward – League Gala and Carnival Successes’, Health and Strength, 41, no. 7 (1927): 180 or ‘Advertisement’, Belfast Newsletter, August 1, 1938, 12.

[73] This was not lost on others. J. Comerford, ‘Physical Culture’, Evening Herald, February 17, 1936, 6.

[74] Eddie O’Regan, ‘Reminisces’ (Hercules Gymnasium, Lurgan Street Dublin, Private Records).

[75] ‘Irish Amateur Lifers’, Health and Strength, 74, no. 51 (1945): 455.

[76] ‘See and Enter for ‘Dublin’s Perfect Man’ Contest’, Evening Herald, January 26, 1939, 7.

[77] O’Regan, ‘Reminisces’.

[78] ‘Ireland’s Best Developed Man’.

[79] See M.F., ‘The Question Box’, The Superman, 9, no. 4 (January 1939): 106; T. Bowen Partingdon, ‘Our Plain Talks Advice Section’, Health and Strength, 1009, no. 6 (1942): 118 or Bowes, ‘Gossip from the Emerald Isle’.

[80] O’Regan, ‘Reminisces’.

[81] Fair, ‘Oscar Heidenstam, The Mr Universe Contest…’

[82] Liam O’Callaghan, ‘Sport and the Irish: New Histories’, Irish Historical Studies, 41, no. 159 (2017): 128-134.

![Introduction to the British Society of Sports History [BSSH]](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Bssh-Banner-440x264.png)