The period 1890-1914 has long been referred to as ‘Cricket’s Golden Age’ with the formidable W.G.Grace as its central figure.

W.G’s last match for England in 1899

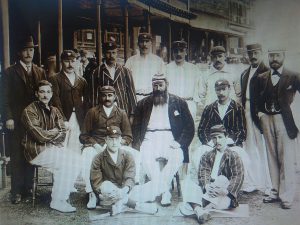

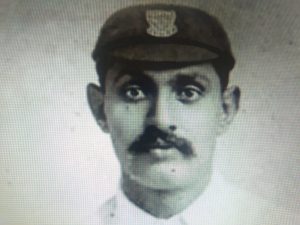

Grace shared the stage with an array of legendary names such as Victor Trumper, A.E.Stoddart, C.B.Fry, G.L.Jessop and the diminutive genius from Nawanger in India, K.S.Ranjitinhji who would became the first non-white sportsman to play cricket for England and the first in the world to gain renown and respect beyond the boundaries of the game. He would come to be known as ‘The Father of Indian Cricket!’

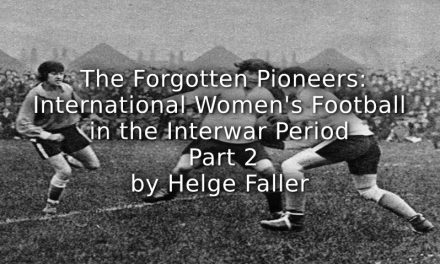

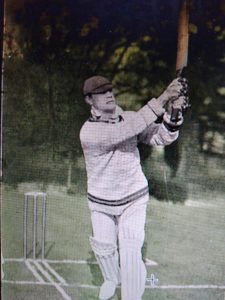

Ranji hitting out

Born in Kathiawar in India in 1872, Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji often referred to simply as ‘Ranji’ (He would become ‘The Maharaja of Nawanger in 1907) had studied at Rajkumar College in Rajkot until the age of 16, when he arrived in Britain to take up his studies at Trinity College Cambridge.

In his early career he was sometimes a victim of racism and despite adopting the pseudonym of ‘Smith’ at Cambridge, his colour hampered his progress and was not selected initially for the University. It would take until his third year to break into the team and become the first player of Indian heritage to gain a ‘blue’ in the 1893 Univeristy Cricket Match.

He joined Sussex in 1895 and scored 77 and 150 on his debut against the MCC at Lord’s and by 1896 it became inevitable that he would be named in the England team to face the Australians in the Ashes series.

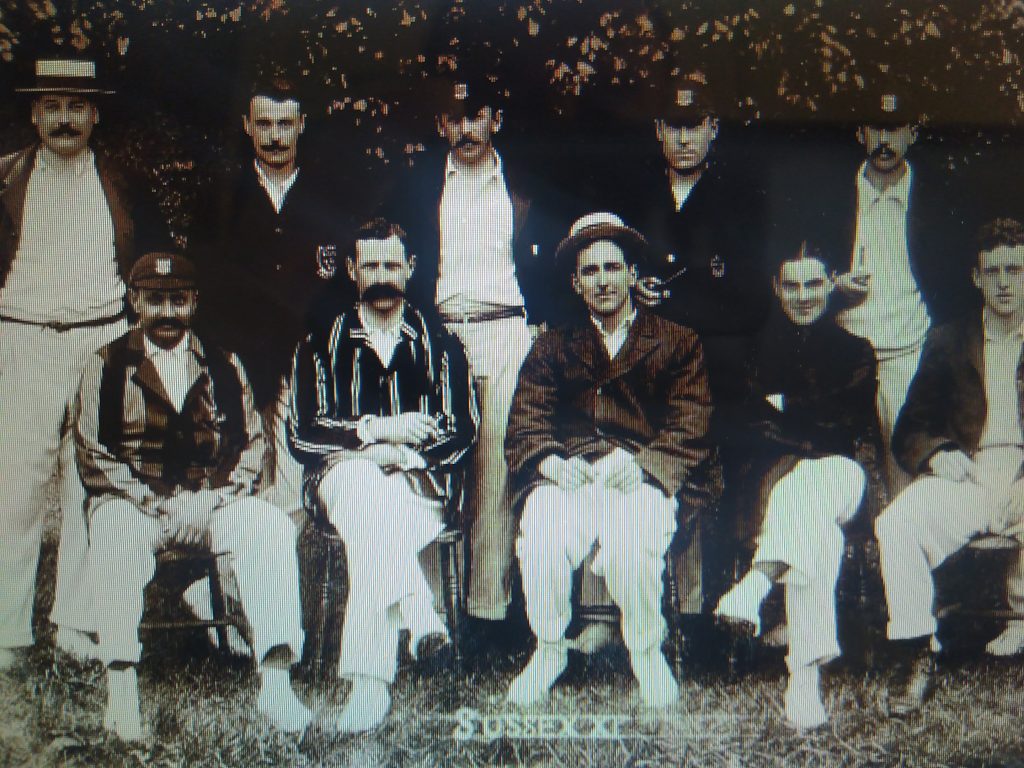

- Sussex CCC Circa 1898

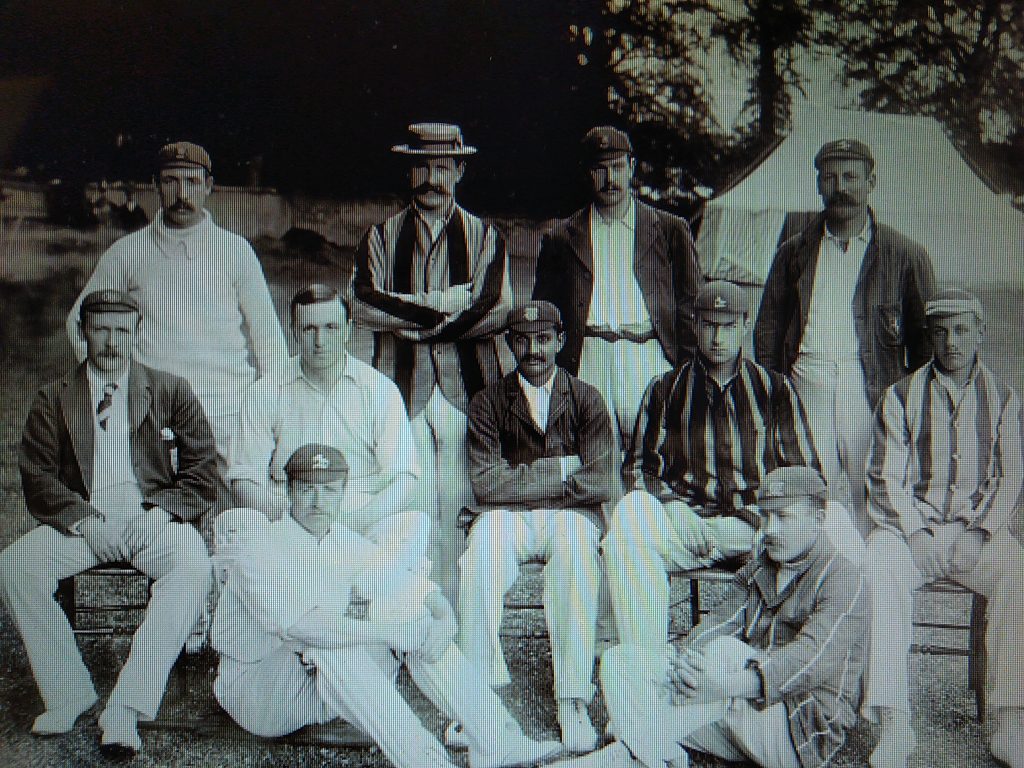

- South of England team to play the Australians in 1896

However, MCC President Lord Harris at the time felt that Ranji’s relationship with England was, ‘too transient and should prevent his selection’, but at that time the selection of the team was down to the hosts of the match and the Lancashire Committee ignored the ‘whites only’ approach and picked him not least because he was likely to bring in the crowds with his flamboyant batting.

In ‘Cricketing Lives’ published in 2021, Richard H Thomas described his debut:

A ponderous 62 in the first innings was followed by a majestic 154 in the second and the only ones still unhappy were those blinded by prejudice. Though not a ‘flag-bearer for his race, Ranji pioneered the notion that cricket need not be a white man’s game!

His spectacular 154 not out which included 113 runs in the 130 minute session meant that Ranji became the first man to score a test hundred before lunch and it was noted that ‘the Manchester crowd cheered as he reached his hundred at 12.45pm.’

The Guardian newspaper reported that,

No man living has ever seen finer batting than Ranjitsinhji showed in this match. Grace has nothing teach him as a batsman!

He would go on to play 15 times for England, scoring 989 runs at 44.95 with two centuries and on England’s tour of Australia in 1897/98 he scored a massive 1, 157 runs at an average of 60.89( which included matches against State teams).

Arguably at the height of his powers in the same year, he achieved something that has never happened again in the history of the ‘first class’ game when he scored two hundreds in the same day; 100 and 125 not out against Yorkshire in August 1896!

In 1897 he produced a book on ‘the evolution of cricket in England’; ‘The Jubilee Book of Cricket’ was published to coincide with Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

The Jubilee Book of Cricket

In his county career he was able to amass 72 centuries and 109 fifties and was the highest county championship run scorer in 1896, 1899( when he became the first player to score 3,000 runs in a first class season) and in 1900!

It is believed that he took advantage of the improving pitches in England and played more shots off the back foot and is associated particularly with the ‘leg glance’ off his hip.

He was also the first of three cricketers hailing from Indian royal families to represent the England cricket team, with his nephew K.S.Duleepsinhji playing 12 times for England between 1929 and 1931 and Iftiikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, who made his England debut on the infamous ‘Bodyline’ series in 1932/33.

Pataudi would also go on to captain India( which became a Test Playing Nation in 1932) in 1946.

Ranji would play his last match for England in July 1902 against Australia in the fourth test and would be dropped in favour of Gilbert Jessop for the final test, where Jessop would go on to achieve the fastest century by an Englishman in a test match scoring his hundred off 76 balls, a record which still stands today, in a match that is now known as ‘Jessop’s Match!’

Gilbert Jessop

In 1907 Ranji assumed the throne of Nawanger after the death of Jem Sahib and many believe that his popularity as a cricketer and his connections with the British administrators in India and the fact that he was ‘westernised’ from his time spent in the UK, were the reasons why he was allowed to succeed to the throne.

- The Maharaja of Nawanger

- Assuming the throne of Nawanger in 1907

In 1914 he helped the war effort by converting his house in Staines into an army hospital for injured soldiers, he donated troops from his Nawanger region to fight for the allies and was made an ‘Honorary Major ‘ in the British Army.

Honorary ‘Major’ during WWI

In 1915 he lost an eye in a shooting accident and played his last match for Sussex in 1920 and as an Indian Prince he took up many political responsibilities and represented India on the newly formed ‘League of Nations’, but sadly died of a heart attack in 1933 at the age of 61.

In ‘Cricket, Literature and Culture’ published in 2009, Anthony Bateman assessed Ranji’s impact and legacy on the sport:

When he did appear as a brilliant amateur batsman for Sussex and England his cultural impact was immense and he was seen by many as an important mediator of Empire

WG Grace put Ranji’s popularity down to ‘his extraordinary skill as a batsman and his nationality’ and Neville Cardus described him as ‘ The Midsummer Night’s Dream of Cricket’

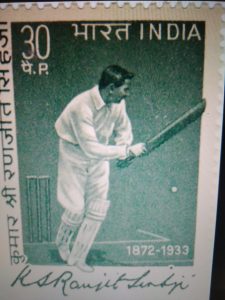

Commemorative stamp 1973

Gerald Brodripp writing in ‘The Croucher’( 1985) a biography of Ranji’s contemporary, Gilbert Jessop, believes that,

Ranji was the most brilliant figure in what many believe was cricket’s most brilliant period. It was during the 1890’s that cricket reached its pinnacle as the National Game and was a synonym of good sportsmanship. Ranji was one of the men who helped to put it there

Mike Huggins in ‘The Victorians and Sport’ ( 2004) described Ranji as , ‘An elegant player who scored runs with style and apparent ease and was hugely popular, attracting the same sort of mass following as had W.G. with bats, matchboxes, hats and hair restorers named after him’.

England team mate Gilbert Jessop also praised him as a sportsman recounting that,

I have never heard him say an ill word of any player whether on his own or on his opponents team! Everyone wanted to see him bat and whenever I bowled against him I felt he was impregnable! He was indisputably the greatest genius cricket has ever produced

Finally, Bruce Talbot from Sussex CCC, writing in ‘A Prince in his Prime’ in May 2020 , concluded by stating that Ranji was ,

arguably the most talented and certainly the most exotic cricketer in a period of brilliantly accomplished flamboyant players

A fine epitaph for a cricketer from any age

The Ranji Trophy 2023

After his death in 1933, The Board of Control for Cricket in India introduced ‘The Ranji Trophy’ and today it remains a domestic first class cricket championship played between city and state teams.

K.S Ranjitsinhji 1872-1933

Article copyright of Bill Williams

![“And Then We Were Boycotted” <br> New Discoveries About the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 3](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Marco-Giani-Boycotted-Part-3-440x264.jpg)