When I was a boy, quite a few coal miners in the pit rows of County Durham kept canaries. Canaries had been taken down the pits from circa 1913 as they were affected by carbon monoxide or methane gas before the pitmen and so gave early warning to those below.

But the working-class links to canary-keeping and breeding go back before that date. The Victorians took canary-keeping to new heights. Canaries were engaging in manner, active, and easy to keep. They were quickly domesticated. By the 1850s the birds could be found in a variety of colours and shapes, including golden-orange Belgians, yellow Norfolks, Yorkshire spangles, and London fancies. As Britain shifted from a predominantly rural to a predominantly urban world, one way that people, men, women or children, could retain a little piece of country in the town was through keeping of a cherished caged canary in their parlour, as an affectionate pet. In a wide range of cultural texts they were depicted as willing captives, excellent singers, and charming and cheerful companions. They were claimed as helping to guide domestic behaviour. Children watching their canary, thought one writer, would learn invaluable lessons of kindness, love and patience, and would help turn potentially socially and morally adults into proper citizens.

Initially the more commercial world of the bird fancier, whether of poultry, pigeons or canaries was largely that of the small trader operating in weekly markets in the mid-nineteenth century. These people sometimes imported birds. German canaries were more valued because their song was much sweeter, though in reality German breeders, largely based in Tyrol and the Hartz, knowing that canaries mimicked songs, taught their birds to sing before exporting them.

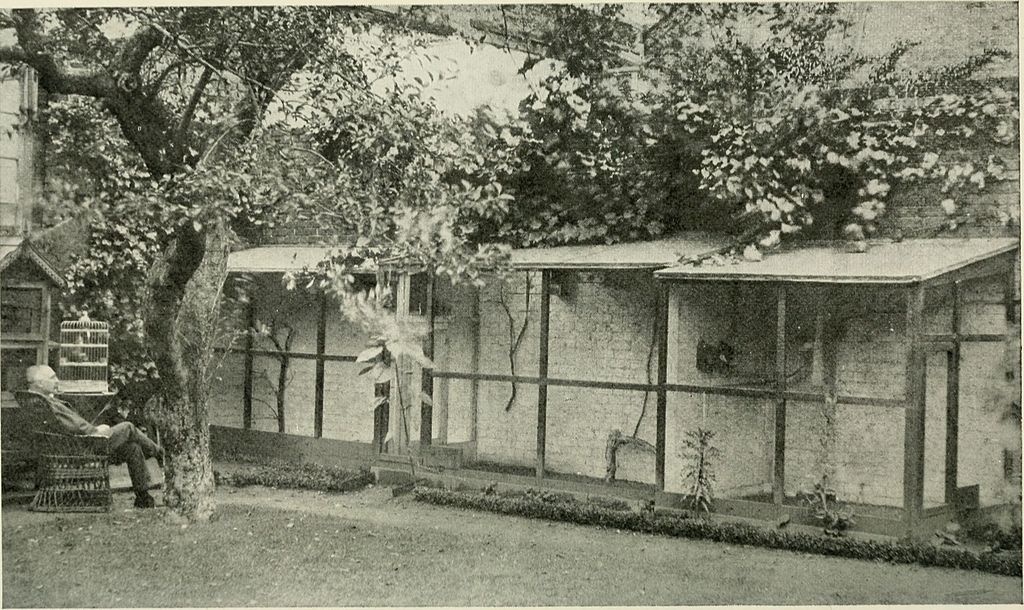

But by the 1860s, as the fashion spread in Britain, artisans, small tradesmen, weavers, hairdressers, cottage gardeners, and others in more sedentary occupations working from their own premises began doing some amateur breeding to augment their earnings, keeping one or two breeding cages, sited to catch the morning sun. Canaries laid three to five eggs per brood from spring onwards. Caring for the birds was a relief from the monotony of work, and the selling of a pair of birds or more could be profitable. But breeding could be risky. There were setting-up costs: breeding cages were not cheap, and feed such as millet, hemp, or pieces of apple needed regular purchase. It took space, since breeding cages were often somewhere round four feet by three feet. So breeding taught some self-denial, using money that could have been spent in other ways. There were dangers: illness, parasites, or attacks by cats or rats if they could gain access.

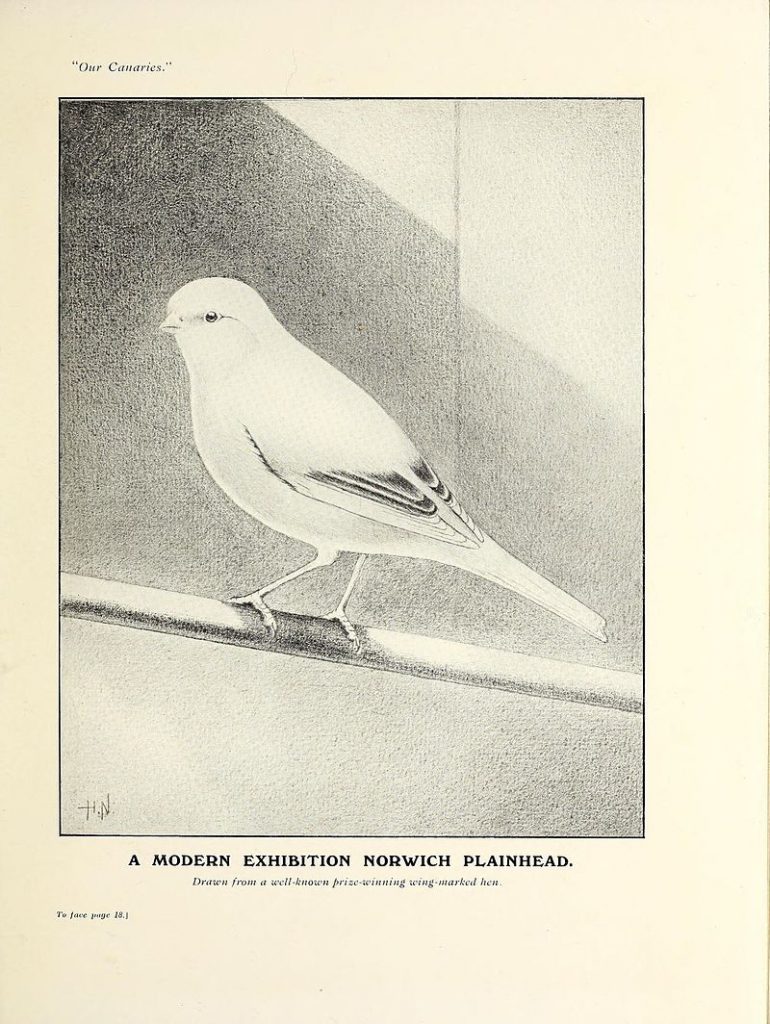

Quite quickly, however, as demand grew some men became more involved in breeding for show, or breeding to sell. Those breeding for show for exhibitions were more concerned with appearance, and ‘improving the breed’. Some shows would stipulate a specific model standard beforehand with breeders breeding to it. In the 1870s at the general ornithological shows taking place in larger cities like Glasgow, canaries were playing a larger role. In 1873 at the ornithological show at London’s Crystal Palace at Sydenham thirty-five out of the seventy-seven classes were for canaries. With the British fondness for associativity, clubs such as the Huddersfield Canary Breeders Society quickly began to form and this further encouraged numbers of canary breeders. By the 1880s these clubs and societies were particularly popular in the midlands at larger towns such as Derby, Nottingham, Derby, Coventry or Northampton, in Yorkshire and Lancashire, and in West Scottish towns like Glasgow or Paisley. Specialist canary shows soon followed. At these ‘amateur’ shows, prizes were often symbolic, silver cups or watches, but also sometimes small amounts of money, perhaps a pound or ten shillings. So winning gained some pecuniary reward, but also gained local and sometimes national status. Newspaper reports suggest some were less than honest, plucking feathers or dyeing plumage to improve appearance.

Publicans, always alert for profit, played a leading role in encouraging these canary clubs. They would offer small prizes for a Sunday show, but ensure that the birds were kept there for two or three days, attracting custom. They would offer free premises for monthly meetings, but demand some sort of minimum spend on food and drink. One Norfolk publican, Henry Spelman, getting involved himself in the 1870s through to the 1890s, expanded his breeding and needed ever-larger space for his cages, buying and selling birds, and competing at leading competitions, as well as holding annual competitions at his inn.

There appear to have been relatively few large-scale breeders. London was a large market, with much demand for birds. Because of the high status of the Norfolk breed, Norwich and its surrounding villages and hamlets was the most important location for commercial canary breeding, with many thousands of small breeders, and, from 1873 onwards, annual exhibitions like the Norwich Alliance and East Anglian Ornithological Association. With Norwich being this key canary breeding centre, it perhaps was only natural that the town’s football club became know as “The Canaries”. By the 1880s Messrs Yallop and the Mackley brothers had become leading figures, operating from Norfolk on a large scale across Britain, exhibiting successfully at major competitions, and importing and exporting birds with breeders in Germany and Belgium.

At this level top-quality birds bought to breed from or for exhibition were expensive, though prices varied with fashion and changes in demand, within a range from perhaps £8 to a pound or two. Some artisans were happy to pay these prices. But pet birds were much cheaper, just a few shillings for perhaps ten years of companionship and pleasure. Canary-keeping has been an overlooked part of working-class cultural life, and its wider social and economic impact is yet to be explored.