Pantomime in Stockport in the 1890s was typical of the pantomimes to be found in theatres all over British Isles at that time. It was a period that brought great change in how theatres were managed and a decade which saw the first exhibitions of film that would begin to be a major competitor for audience share as the Victorian era gave way to the twentieth century. At this time many independent theatres were being bought up by commercial syndicates. By 1903 United Theatres owned the three leading theatres, in Manchester city centre, just seven miles away – The Theatre Royal, The Prince’s Theatre and The Gaiety Theatre.

The Theatre Royal and Opera House in Stockport was the flagship theatre of an independent circuit of theatres owned by the Revill family. It was built by William J Revill, opening in1888 and owned and managed by his descendents until its closure in 1959. At the height of their success they also owned theatres across the North West of England in Ashton-under-Lyne, Macclesfield, Bury, Rochdale, Wigan and St Helens, and further afield in Sheffield, Derby, Middlesbrough, Leicester, Stoke Newington and Holloway. The building was eventually demolished in 1962. As we shall see later, this model of ownership had an influence in the tradition of producing independent, in house pantomimes for many years after the large commercial operators whose theatres functioned as receiving houses during the rest of the year had chosen to also import touring generic productions for their pantomime seasons.

- The Stockport Theatre Royal and Opera House (1888-1962)

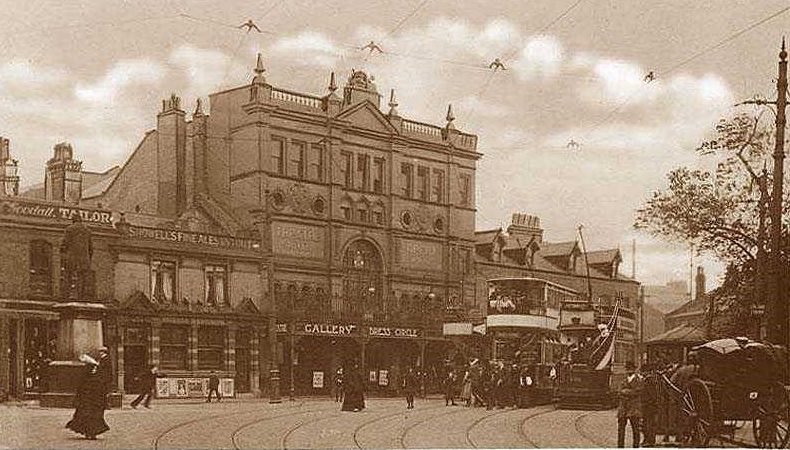

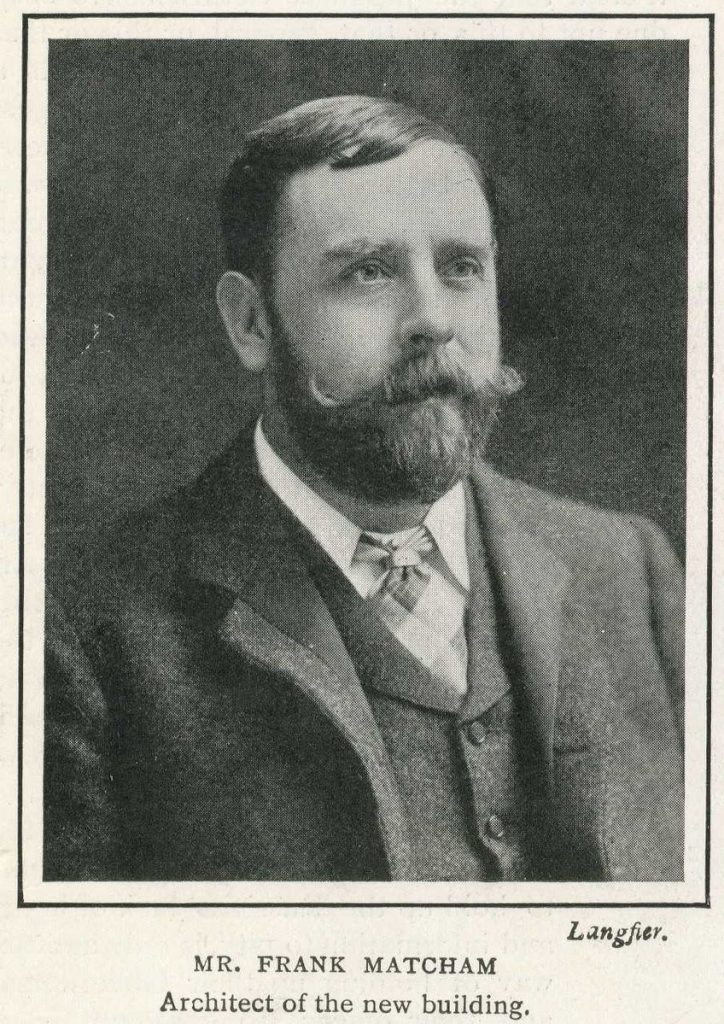

William J Revill had owned a theatre on the same site since 1870, choosing to demolish it after a fire seriously damaged the stage and backstage areas of the building after the theatre had closed on the night of 25 August 1887. He commissioned the rising young architect Frank Matcham to design his new theatre. Matcham had gained experience working on remodelling several existing theatres, but this was the first new theatre he was responsible for. The new Theatre Royal and Opera House bore little external resemblance to the trademark domes of the style Matcham, often regarded as the greatest theatre architect of his day, would become recognised for in later work. Some of these can still be seen at the nearby Buxton Opera House (1903), Blackpool Grand and London’s Shepherd’s Bush Empire. Many modern features were incorporated into the design of the new theatre’s interior including safety features for the audience and the clear sightlines and superb acoustics from every seat in the house that Matcham became especially noted for.

- Frank Matcham (1854-1820)

Revill and Matcham included the very latest design features in the new theatre facilitating the production of the fashionable ‘high tech’ pantomimes of the day. When Revill retired, just a couple of months before his death in 1897, his son Charles, already the director of the Theatre Royal in Ashton under Lyne, took over the management of the Stockport theatre. From him, it later passed down to another William Revill, grandson of the founder. The theatre closed on his retirement in 1959. He died in 1967. For the purpose of differentiation between the two Williams, we will refer to him a William Revill Jr here.

It is this younger William Revill Jr to whom we owe much of our knowledge about how his grandfather produced pantomimes that rivalled the theatres of central Manchester for their grandeur, spectacle and popularity throughout the 1890s. Shortly before he retired he was invited to write a series of articles for the local newspaper, the Stockport Advertiser, detailing his memories of how, as a child, he had observed the workings of the business that involved all the family. Much of parts two and three of this series of articles is taken as direct quotes from his pieces, which are so evocative of that time.

Links to more information about the theatre itself can be found at the bottom of this page.

Pantomime in the Nineteenth Century

The secret to the long history of pantomime and its success in achieving great popularity with new audiences down through the generations can be found in the one element which can truly be said to be ‘traditional’. Pantomime has succeeded in being reinvented by every new generation. Each generation retains some elements of the pantomime hand to it and adds new elements of its own. Each generation would give you a different description of a ‘traditional’ pantomime. This is because, it has a function is to hold up a satirical mirror to the current state of society. Each year’s new pantomime is a snapshot of how we live ‘now’, whenever that now might be. Relatively few pantomime books of words have survived to the modern day, or been produced again after their initial run, because they were not valued enough to be thought worth preserving. They were seen as temporary and disposable, to be replaced with something new the following year.

Early form of pantomime can be traced back as far as ancient Greece. The name is derived from the Latin word ‘pantomimus’ which translates as ‘imitator of all’. The Oxford English Dictionary describes it thus:

A dramatic performer popular in the Roman Empire who represented mythological stories through gestures and actions, supported by music and a chorus, playing all the roles in a piece, each role having its own mask.

Italian performers brought the commedia dell’arte to Britain in the sixteenth century. Music, dancing and mime were vital to theatrical performance in Britain at that time. It was illegal for the spoken word to be heard on the British stage, except in theatres granted the royal patent by the monarch, until the Theatres Regulation Act of 1843 was passed in Parliament.

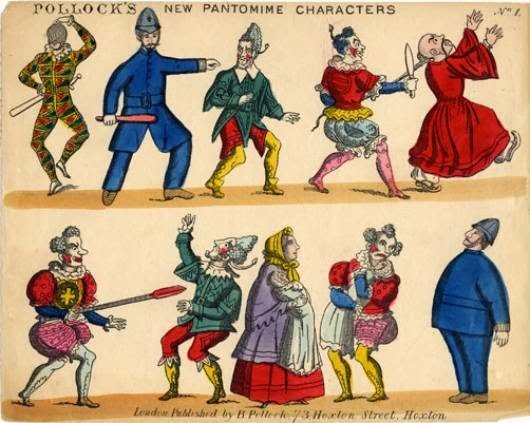

- Characters of the Harlequinade

During the nineteenth century, pantomime underwent two major transformations. When Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, pantomime was a bawdy, political satire with a short ‘opening’ which quickly underwent a transformation scene introducing the main action of evening, which at that time was the harlequinade. It was regarded as subversive and not a family entertainment. The stock characters of the harlequinade – Harlequin, Columbine, Clown and Pantoloon, are easily seen to have derived from the commedia dell’arte. Aided by the Theatres Act of 1843 and Queen Victoria’s taste for visiting the pantomime, high Victorian pantomime evolved into its most spectacular, extravagant form. The ‘opening’ gradually expanded to become the main feature of the show, while the harlequinade reduced in length until it became a ten minutes afterthought directed at children. Theatre managements invested vast amounts of time and money into the ‘annual’ vying with each other to have the most successful season each year. They were even competing with themselves to be more successful than their own previous pantomime productions. Here the managers took advantage of new modern technical innovations in engineering, gas lighting and eventually electricity to produce special effects. At the height of the vogue for the spectacular form of pantomime, it was not unusual for reviews to comment solely on the scenery and effects, without ever mentioning the performers.

- Pantomime fairies

As the investment each year became recognised by industry professionals to be getting out of hand, and it was becoming impossible to devise any new spectacular novelty that could surprise the audience, pantomime evolved again from the mid 1870s onwards, They spent a little less on the extravaganza elements and now relied on the introduction of music hall stars and more opportunities for the audience to sing along to current favourite popular songs. The performer was now centre stage again and the main concern of the reviews.

Pantomime in 1890s Stockport

As is the case with many UK theatres in the twenty-first century the annual pantomime was the most lucrative production of the year, and a successful pantomime was essential to subsidise potential losses during the rest of the year. A failed pantomime could easily lead to the closure of many theatres. The commercialisation that saw the rise of theatre syndicates also witnessed changes in production where theatres around the country operated as receiving houses, taking in productions by touring theatre companies. Pantomimes were also beginning to be toured in the way, but for many theatres around the country, it was the one opportunity in the theatrical calendar for the theatre staff to create their own in house production. In the earlier Victorian era theatres usually produced all the shows they presented were all in house productions and by the 1890s many of a theatre’s staff had previously been performers. The in house pantomimes were able to retain a local flavour with jokes aimed at the theatre manager and local dignitaries and personalities. Theatre staff often revived their past careers as performers to take a part in the pantomime or in designing and making its sets, props and costumes. The libretto, or pantomime ‘book of words’, would often be written by a member of staff or a local journalist. The extravagance of producing a spectacular pantomime also often provided some temporary employment and excitement for local people, including children, inspiring a sense of community. Much of this local excitement and pride was lost when pantomimes were provided by touring companies. Where towns had more than one theatre these independent productions created rivalry over their ‘annuals’ between the managements, not only for who could make most money, but whose show was most popular and which received the best reviews. For the Revill family, they were able to replicate some of the economies of scale achieved by the larger circuits, by reproducing their own pantomimes in their own theatres. For example the 1889 production of Dick Whittington at the new Ashton under Lyne theatre, followed the presentation of Dick Whittington in Stockport the previous year. The insights that William Revill Jr gives in his firsthand accounts of how his grandfather and parents worked for months to bring the annual pantomime to the stage and both illuminating and entertaining.

- Babes in the Wood – A spectacular pantomime at Manchester’s Theatre Royal. (1883-1884). The Illustrated and Sporting News. 3 February 1884

Article © Claire Robinson

In Part 2 we will be looking at how Little Red Riding Hood, William J Revill’s pantomime for the 1891-1892 season, was made.

Part 3 discusses the experiences of audiences attending the Stockport Theatre Royal and Opera House’s pantomime and the reviews for Little Red Riding Hood.

A video compilation of images of the theatre exterior can be found here: https://youtu.be/OyOMA36Udqc

More information about the history of the theatre itself can be found here: http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/StockportTheatres.htm

References

Please can you tell me where Revill’s theatre in Macclesfield stood?