The first in a 5 part series about the life of Clarice Vizard (1895-1978), nee Singleton, a forgotten but important female football administrator in the early 20th century. She was one of the few named female team managers between 1917 and 1921. She ran the Bolton side, which was sometimes called Mrs Vizard‘s XI, and she was in charge when DK Ladies were beaten for the 1st time in 1918. She was called the ‘Manageress’ in some newspapers.

Image 1: Clarice Vizard standing second from the left at Bolton train station, 1929.

(Jimmy Seddon Collection, National Football Museum.)

Ted Vizard’s wife acts as trainer and manageress of a Bolton Ladies football team. Sheffield Telegraph and Star Green’Un, 11 June 1921.

In the collections of the National Football Museum, in a scrapbook kept by Bolton Wanderers captain Jimmy Seddon, a photograph captures a once pioneering female football manager. Taken in 1929 at Bolton Train station, it captures Clarice Vizard waiting for her husband, Bolton Wanderers and Wales winger Edward “Ted” Vizard, to return with the FA Cup, the third such triumph in a golden period for the club. Just a few years earlier, Clarice had been carving out her own niche as the “manageress,” seemingly one of the few women running a leading women’s team in post-First World War football. The Bolton Ladies side she ran were sometimes referred to as Mrs Vizards XI, indicative of both her role in organizing the side and how women’s identities were subsumed into those of their husbands upon marriage.

Today, female managers are still a minority at elite level. At the time of writing, they amount to only 25% in the FA Women’s Super League. This reflects a long-term trend for managers of women’s teams to be men, stretching back to the early twentieth century. Men such as Alfred Frankland at Dick, Kerr’s Ladies, Percy Ashley at Manchester Corinthians, and Harry Batt at Chiltern Ladies are some of the better-known figures, all of whom played an important part in the development of women’s football.

The challenge for historians is finding and researching the lives of early female pioneers in football management and administration. They have been present since the 1890s with Nettie Honeyball of the British Ladies FC. Another key early figure is Diana Scott, credited as a pioneering figure in Irish football in the 1910s and 1920s. In later years there were women who formed and worked for the Women’s Football Association in 1969.

Clarice was another such figure. However, her career has been largely unknown until now. Like many players, teams, and officials active in women’s football in the early 1920s, her interest in football was curtailed by the English Football Association’s 1921 ban on its clubs hosting women’s games. Had this not been introduced, and women’s football encouraged or even just tolerated, it is conceivable that her story would be much better known today. Instead, over the following five articles I hope to introduce readers to an outline of her life and to argue for her importance to the early history of women’s football.

In many ways though Clarice’s story is not about football, but what she did without it. For a brief period, it gave her a role and fame beyond that of her husband’s career. But it was just one part of her life that saw her become a telephonist in Britain’s burgeoning telecommunications industry, a wife and mother, a local Conservative Party activist, a Chief Commander in the Army Territorial Service in the Second World War, before concluding with running a pub for over twenty years with her husband. It might be considered a twentieth century life story that reveals something of women’s lives and how they changed, particularly in reference to the two World Wars.

From Annie Clara Singleton to Clarice Vizard.

What should name should we call her? When Clarice Singleton married Edward Vizard on New Years Day 1918, it was not the first time that her name changed. Born Annie Clara Singleton, somewhere along the line she adopted Clarice as an alternative. Such preferences were not unusual among Victorians and Edwardians, with many using middle names to distinguish themselves from parents with the same name. But in Clarice’s case, it was perhaps one way of separating herself from a painful adolescence marked by a family scandal.

Born on the 30 January 1895, Annie Clara was the youngest of five children born to Walter Alfred Singleton (born 1864, date of death unknown) and Annie Margaret Singleton (born about 1867, died about 1934) in Bolton in Lancashire, when the 1901 census was taken.[1] They lived with a domestic servant which indicates that the family were lower middle-class. Walter was a Master Baker, and with his elder brother William, ran a prosperous family bakery that had been established by their father. William and his wife Margaret had four children of their own, with the elder two assisting as shop baker’s assistants. We might imagine two closely linked families, with the cousins mixing with each other at the bakery.

Within a few years this prosperous business would be shut. It fell victim to a gambling addiction that ensnared William and Walter, leading to their bankruptcy in 1904. The bankruptcy proceedings, as reported in the Bolton Evening News, paint an unpleasant picture, as the two brothers squabbled over who was responsible. William did not know how much he had lost but “thought it would be from £200 to £300.” By contrast, Walter seemed to be in denial, “he did not think he had lost £500 by gambling, or that his gambling did anything to bring about the bankruptcy.”[2] Given that a First Division footballer on the maximum wage of £4 per week would have earned just over £200 a year, such amounts were more than significant. Six years later, William died, aged 53.[3]

Image 2: Bolton Evening News, 7 December 1904

(With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive)

The bankruptcy not only ended the business, but also Walter and Annie’s marriage. In May 1909 Annie summoned Walter before the Borough Police Court for abandonment. Initially, the case was adjourned as Walter improved his behaviour, but by October it had deteriorated to the extent that he was summoned again. The court heard how Walter, now running a photographer’s business, lived with his family, but had given them only £4, 9s in the last six months. “He had his food with them, but if any meal did not suit him, he went out and bought something for himself, and took it home, but never took anything for anyone else. The family had now got tired of keeping him, and if he stayed home they would leave.” Relations had deteriorated to the extent that Walter was said to be threatening to leave the country if an order was made against him. The bench sided with Annie, granting a separation order, and ordering Walter to pay his wife 12s, 6d per week.[4]

By the 1911 census, Annie Clara, now sixteen years old, was living with her mother and three of her elder siblings. She and her twenty-one-year-old sister Jessie were employed as telephone operators for the Telephone Co Ltd, along with another 36 or so other women in Bolton. They part of a new field of employment for women in Britain’s emerging telephonic communications industry.

‘To the Invisible “She”, the ‘Maiden, whom we never see.’

Invented in 1876, the telephone was becoming part of everyday life in Britain in the 1910s when Clarice became an operator. It was still an expensive item, with use restricted mainly to businesses and wealthier people. At the heart of the telephone industry for the first 80 years or so was the telephone exchange. Unable to use dedicated lines between one user and another, callers were connected by ‘Hello Girls.’ These women took the initial call and then connected it via jack plugs on the switchboard or connecting it to another exchange.[5]

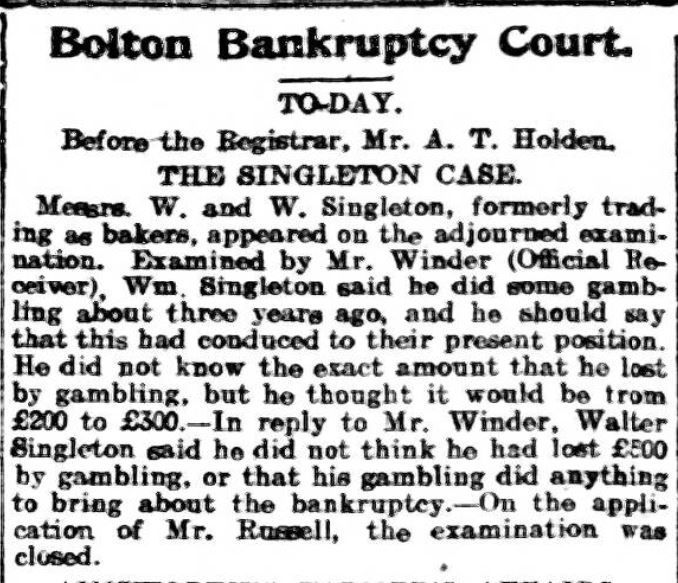

Image 3: Illustrated London News, 5 October 1907.

This photo of a London Telephone Exchange gives a feel for Clarice’s working environment.

(With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive)

As Dr Helen Glow explains, the telephonist in Britain ‘was gendered female almost from the beginning of its existence.’[6] Her article, ‘Maiden, whom we never see: Cultural Representations of the ‘lady telephonist in Britain, c.1880-1930, and institutional responses,’ helps situate Annie and her sister in the wider emerging world of urban, white-collar female workers.

The telephone industry in Britain was unusual because by 1912 it was almost entirely under public ownership through the General Post Office (G.P.O). Initially boys were used but they were soon replaced by women. Contemporary notions of femininity meant they were seen as better suited to sitting still, being polite, and being able to operate a switchboard. Social attitudes and employer policies also allowed the G.P.O to pay women less than men and operate a strict marriage bar.

Telephonists tended to between the ages of 16-18 when recruited, helping popularise the image of the young female telephone operator. They were usually recruited from lower social classes than female clerks and telegraphists, but the G.P.O had strict criteria about having good diction and ‘clear, accent-less voices.’ This was coded language about women sounding ‘appropriately middle-class.’[7]

Glow describes the work that Clarice and her colleagues undertook as ‘simultaneously skilled, stressful, repetitive, and interchangeable with that of colleagues.’[8] There was a minimum height requirement of 5 foot in 1902 to ensure they could reach all the switches. Concerns over the physical nature of the work lead to an official enquiry in 1910. Three medical professionals visited exchanges, interviewed staff, and tested the equipment and office furniture. Glow describes how the enquiry found that,

while it was no more dangerous to women’s bodies than other office work, there were concerns around the pressure of the equipment, the seating, and poor treatment by subscribers, ‘all of which contributed to mental and physical strain not usually found in other kinds of work.’[9]

The physical and mental strain was in part due to the volume of calls, which might be as many as 1,600 per eight-hour shift in one Manchester exchange.[10] But another key factor was the behaviour of callers, influenced by contemporary attitudes to women and arguably reinforced by contemporary media presentations of telephonists.

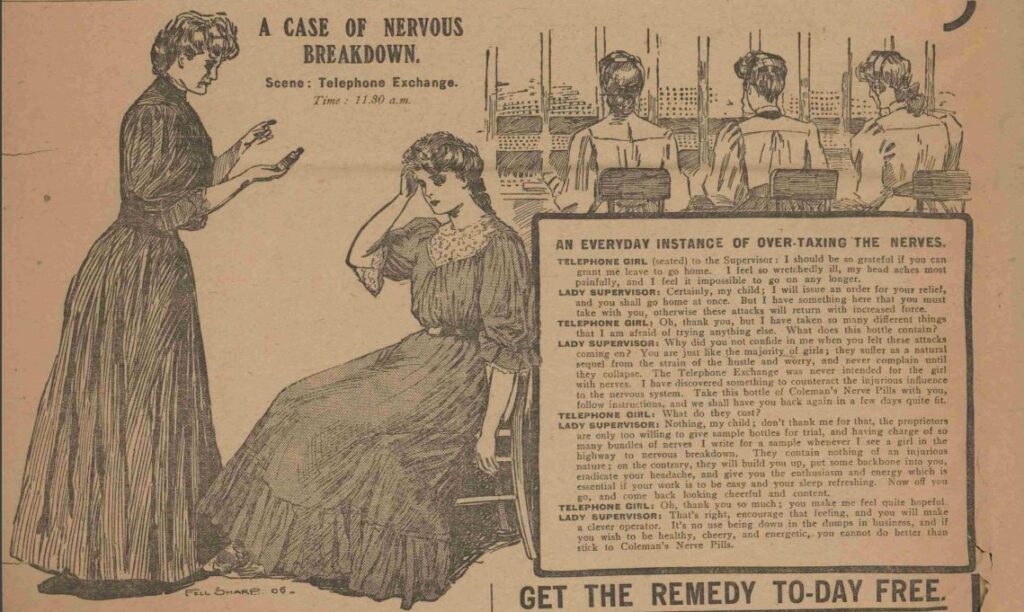

Image 4: Daily Mirror, 2 October 1906.

A Coleman’s Nerve Pills advert focusing on the pressures of being a ‘telephone girl.’

(With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive)

Until the First World War, telephones were largely used for business calls and majority of users were middle and upper-class men. Contemporary complaints or prejudices focused on women being suited to the work because it allowed them to chat and hear gossip, but also being unreliable (they were blamed for any faults with the equipment) and rude (in their role in connecting and de-connecting calls). There was a growing awareness though that while telephonists could be issued instructions and advice on speaking protocol, users also needed guidance, with the Daily Chronicle printing a poem on this theme dedicated to ‘The Invisible “She”, the ‘Maiden, whom we never see.’[11]

Beyond her work, we have some glimpses of Clarice’s social interests. She enjoyed singing and was active in several groups who performed in Bolton. In 1910 she sang as part of “Tony and Terry’s Comedy Kiddies” in aid of a Church Building Fund, while in 1913 she was part the chorus in “The King of Cadonia” by Bolton Operatic Society. The following year she progressed to a named role (Mademoiselle Chic) in the Society’s proposed performance of “Cingalee.” However, the performance never took place. The casting news was announced on the 1 August but four days later Britain was at war with Germany.[12]

It is through music that we can continue to glimpse Clarice through the early years of the First World and her involvement in the local war effort. One way for civilians to support their country was through volunteering their time. In Clarice’s case, she performed at supper aid concerts for wounded soldier, ‘where some of the best musical talent of the town give their services.’[13] She performed as part of the Vaudettes, a mixed-sex group of six to eight singers.

It was perhaps around this time that she became acquainted with Edward “Ted” Vizard. Born in Cogan, Wales in 1889, Edward emerged as a talented winger with Barry before joining Bolton Wanderers in 1910. He soon became a regular in the team and in 1911 he received the first of 22 Welsh international caps. With the outbreak of the First World War, professional footballers came under social pressure to enlist. The pressure increased in the summer of 1915 when the FA banned the payment of players, leaving players with the choice of joining the army or finding new civilian jobs. Like many players, Edward found work in the rapidly expanding munitions industry. He did enlist under the Derby Scheme in late 1915, although it was not until Conscription was introduced in early 1916 that he was formally called up, along with his partner on the Bolton Wing, England international Joseph “Joe” Smith.

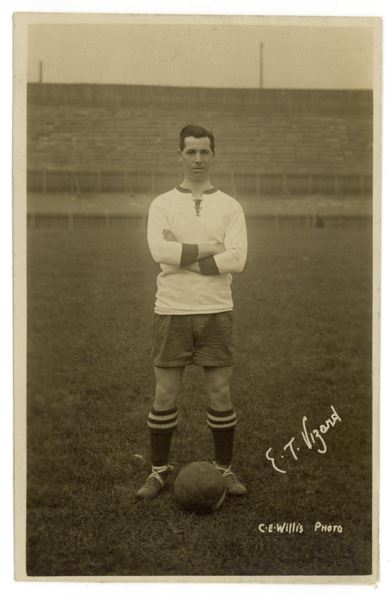

Image 5: Postcard of Edward “Ted” Vizard, Bolton Wanderers, c1920s.

Jimmy Seddon Collection, NFM.

Joining the army was not the end of Edward’s footballing career – far from it. He and Smith underwent training for the Royal Field Artillery, but they also played for leading clubs as guests as well as for army sides. Completion of their training did not mean though that they went overseas. Instead, they were posted to the north-east of England where they continued to play for military and local sides, and when leave could be secured, for Bolton Wanderers. This pattern continued when he was posted to Wiltshire with the 413 Reserve Brigade.[14]

Edward was presumably on leave when he married Clarice on New Year’s Day 1918. It was probably not a long event, as Edward played for Bolton at Bury in the afternoon, with the club making him captain ‘in honour of the event.’[15] Due to the G.P.O.’s marriage bar Clarice had to resign her job, and the Royal Mail Pension and Gratuity Records notes the start of her pension.[16] By the summer Edward has passed his gymnastics instructors course, earning a promotion to Sergeant-Major, and was reported to have been posted overseas. If so, he wasn’t away from Clarice for long, as he was released from the army in February 1919, whereupon he became player-manager of Bolton Wanderers for the remainder of the season. By this time Clarice was managing Bolton Ladies, making their household perhaps unique in England by hosting the managers of the town’s leading men’s and women’s teams.

To read PART 2 – Click HERE

References/Notes

[1] Her siblings were William J (9), Jessie (11), Walter S (13), Minnie (14) and the servant was Ellen Moss (24). Further details on Walter and Anne taken from England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, and UK, Buriel and Cremation Index, 1576-2014, accessed 27.12.2024.

[2] Bolton Evening News, 6 July, and 7 December 1904.

[3] Bolton Evening News, 17 November 1910.

[4] Bolton Evening News, 2 October 1909.

[5] https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/goodbye-hello-girls-automating-telephone-exchange accessed 30.12.2024.

[6]https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/download/243a7d67264c56b04af0e179a22aec5d15e054feb283d176fcb7d15ea259df21/124284/Ferguson%20et%20al_final_web.pdf accessed 27.12.2024. Page 4. The following descriptions of the telephone industry and telephonists is drawn from her work.

[7] Ibid, p.5.

[8] Ibid, p.5.

[9] Ibid, pp.20-21.

[10] Ibid, p.14.

[11] Ibid, p.14.

[12] See Farnworth Chronicle, 22 January 1910 and 1 August 1914, Bolton Evening News, 16 December 1913.

[13] Bolton Evening News, 5 August 1915. See also 9 April and 10 November 1915, 26 January and 14 July 1917, 26 December 1916, Farnsworth Chronicle, 6 October 1916.

[14] For information about Smith’s wartime career see, Athletic News, 7 June 1915, Birmingham Sports Argus, 26 February 1916, Yorkshire Weekly Record, 17 February 1917, Nottingham Football Post, 29 September 1917, Sheffield Green’Un, 8 June 1918. Also, their marriage record at England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1916-2005, accessed 27.12.2024.

[15] Evening Dispatch, 2 January 1918.

[16] UK, Royal Mail Pension and Gratuity Records, 1860-1970, accessed 27.12.2024.