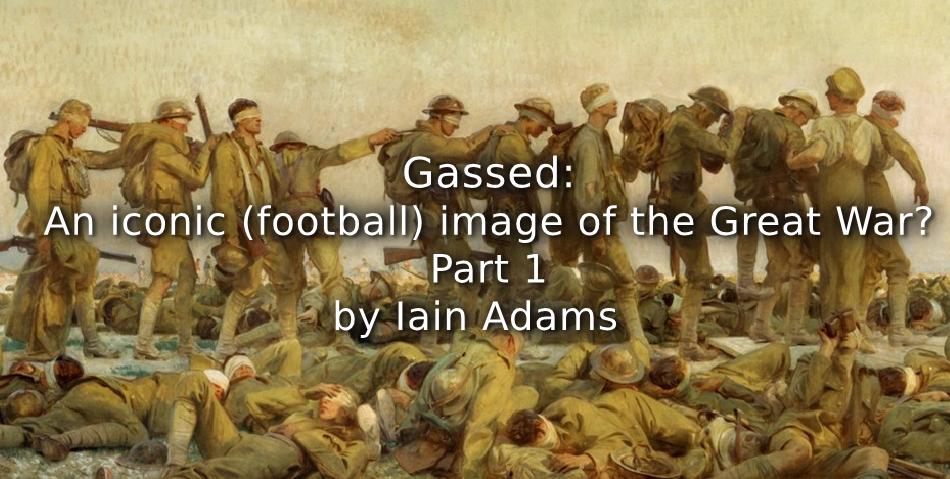

This article explores the contentious meanings of the football match in John Singer Sargent’s ‘Gassed’ alongside identifying the stage and actors.

John Singer Sargent

In the early twentieth century British art was dominated by The Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition which traditionally marked the start of the London ‘season’. These exhibitions continued throughout the First World War although with reduced visitors. The 1919 Exhibition marked a return to pre-war visitor numbers with over 210,000 people viewing over sixteen hundred works.[i] The Times, in its first report of the 1919 exhibition, reported:

The “picture of the year” is of course Mr. Sargent’s “Gassed” … It should be seen first from a distance… It is a picture which no critic could pretend to judge finally at a first seeing. The intention is clear at once. A train of soldiers, gassed, blinded, and bandaged, is led across the canvas, no doubt from a clearing station, to some place of rest. The ground is crowded with soldiers lying down and also gassed; and there is another train moving on the right of the canvas. Far behind are soldiers playing football; and this background is a kind of counterpoint to the procession of pain in front (Figure 1).[ii]

Figure 1. John Singer Sargent Gassed.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (IWM Art 001460)

The painting was submitted to the exhibition by its owner, the Imperial War Museum (IWM). The IWM’s art collection has over eighty-five thousand items, including paintings, prints, drawings, posters and sculpture. The in-house magazine, Breakthrough, has noted ‘among the artworks is our most significant work – Gassed by John Singer Sargent’.[iii]

Sargent was an American artist born in Florence in 1856. His father was a surgeon and his mother always ‘painting, painting, painting’. It was her desire to dwell in the midst of high art and culture that led her and her husband to leave Philadelphia and live in Europe. Sargent’s parents took their children through museums ‘from the Vatican to Venice’ and Sargent became a keen artist at an early age. His friend and biographer, Evan Charteris, noted that his early ‘drawings were precocious, not in imagination, but as literal records of what was immediately before him’, done for the sheer fun of translating what he saw onto paper.[iv]

In October 1874, at the age of 18, Sargent settled in Paris and joined the studio of Émile Carolus-Duran, the foremost portrait painter in Paris. Three years later, in 1877, he submitted his Portrait of Frances Sherborne Ridley Watts to the Salon, the premier art exhibition of France. This exhibition was organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris and their jury selected works for the exhibition. His painting was well received and made him one of the most sought-after portraitists of the time.[v] However, his 1884 submission to the Salon, Portrait of Madame X, scandalized the subject, Madame Pierre Gautrea, her family, and Parisian society in general. Madame Gautreau moved conspicuously through Parisian society ‘shining as a star of considerable beauty’ and drawing attention ‘as one dressed in advance of her epoch’.[vi] The painting emphasised her daring personal style with a deep décolletage and the pose was considered sexually suggestive with the right strap of her dress slipping from her shoulder. Sargent later over painted the shoulder strap placing it back over her shoulder. He kept the painting for over thirty years before selling it to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art stipulating the museum should disguise the sitter’s name. Sargent wrote of Madame X in a letter to the Museum’s director in 1916 ‘I suppose it is the best thing I have done.’[vii] The extent of the negative reaction resulted in Sargent feeling obliged to depart for Britain where his art matched the spirit of the age. He quickly became the leading portrait painter of the generation and was elected to the Royal Academy in 1897.

Sargent: War Artist

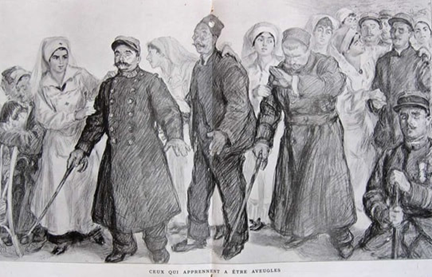

His success in Britain enabled him to follow his main interests of painting murals, and working and completing art works outdoors, en plein air. He was on a trip to the Dolomites when war broke out in August 1914 and, failing to realise its significance, he continued his visit into November. On his return to Britain, several unsuccessful attempts were made by British war artist schemes to induce him into their fold. The war began to impact upon him when his niece’s husband, Robert André Michel, a French Army infantry Sergeant, was killed in fighting on October 13, 1914. His niece, Rose-Marie Michel, was a favourite muse and pre-war had accompanied Sargent on several of his sketching tours and featured in a number of his paintings such as Cashmere, The Pink Dress and The Brook.[viii] Rose-Marie began serving as a nurse in a rehabilitation hospital for blinded soldiers at Reuilly following the death of Robert. In May 1915, L’ Illustration published an etching by Paul Renouard of injured soldiers from various allied countries in which Rose-Marie featured, the third nurse from the left helping a Serbian soldier who is vainly trying to see his hand held close to his eyes (Figure 2).

In early 1915 Sargent returned his Prussian Order of Merit for Arts and Science which had been awarded in 1908 and, by July 1916, he was contemplating becoming a war artist. He wrote to Evan Charteris wondering whether he would have ‘the nerve to look, not to speak of painting?’[ix] On Good Friday, March 29,, 1918, a shell from a German long range siege gun, struck St-Gervais-et-St-Protais Church killing ninety-one people and wounding sixty-eight. Rose Marie was one of those killed. This, no doubt, influenced his decision to become a war artist.

Figure 2. Paul Renouard. Those Who Are Learning to be Blind

L’Ilustration, 3768, May 22, 1915, 518

British War Artist Schemes

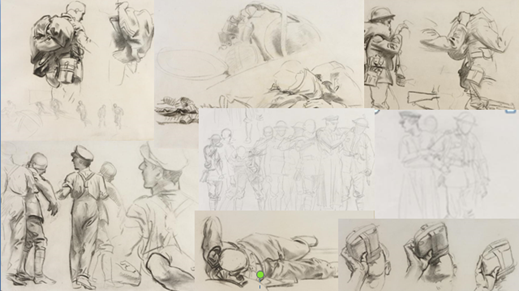

The British First World War art schemes, beginning in August 1914, ‘were an unprecedented act of government sponsorship of the arts’.[x] The first official war artist sent to the front was the Scottish etcher Muirhead Bone and by late 1916 Bone had completed over 200 drawings, including Artillery Men at Football (Figure 3). This black chalk and wash drawing has never been displayed and has been in storage since it was sent by Bone from France to the War Propaganda Bureau in 1916. It is interesting as it shows the artillery men off duty, the foreground furrows leading down to a flat area in the middle distance where a football match is in progress; the living quarters of the gunners, bell tents, are in the distance.

In March 1918, Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Information, created the British War Memorial Committee (BWMC) of which Bone was a member and artists were engaged to create a Hall of Remembrance. This was to be a ‘legacy for future generations, an emblem of remembrance, a lasting memorial expressed in art’ to Britons who had given their lives during the war. The Hall, which was never built, was to be centred upon four ‘super-sized’ paintings to be created by Augustus John, William Orpen and Sargent, the fourth painting was never commissioned. Completed works were given to the IWM.[xi]

Figure 3. Muirhead Bone. Artillery Men at Football.

Courtesy of Natalie Bone and The Bone Estate. IWM: IWM ART 2182

On April 26, 1918, Alfred Yockney, the secretary of the BWMC, wrote to Sargent asking him to commemorate Anglo-American co-operation, but seemed to be so keen to recruit him that he was more-or-less offered carte-blanche with regard to subject matter. Yockney wrote a letter to his fellow committee member Bone stating that Sargent was the ‘keystone of the arch’ of the project. Bone thought the BWMC should ‘humour Sargent in every possible way’ in a responding letter. The appeal to Sargent to become a war artist was supported by a letter to Sargent from the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. Sargent agreed to the commission in June 1918.[xii] Sargent was a tactful choice for a commission symbolising the co-operation between British and American forces.[xiii]

Sargent as a War Artist

Sargent and, his friend and fellow artist, Professor Henry Tonks, departed for France on July 2, 1918 assigned to the Guards Division of IV Corps, British III Army. This was seemingly a surprising place for studying Anglo-American co-operation because the American Expeditionary Force was attached to the French First Army, some 40 miles to the south. It appeared to have been just another administrative ‘cock up’; but recently released documents show that in secret preparations for the third Battle of Albert, the United States II Corps were operating with British III Army units with whom they were to be assigned for the battle.[xiv] In light of Sargent’s commission, it seems probable that both Sargent and Tonks were privy to this information.

However, Sargent and Tonks found little of interest to paint and went to Arras in August in search of subjects. Whilst there, on August 20 they heard that the III Army was opening its offensive of the third Battle of Albert on the following morning, August 21, and the Guards Division to which they were attached was involved. They decided to drive towards the division after lunch on August 21. Tonks recorded that on August 21:

…. after tea we heard that on the Doullens Road at the Corps dressing station at Bac-du-Sud there were a good many gassed cases, so we went there … Sargent was very struck by the scene and immediately made a lot of notes. It was a very fine evening and the sun toward setting (Figure 4. Note the football players, middle sketch left hand side).[xv]

Figure 4. John Singer Sargent. Studies for Gassed.

Courtesy IWM, © IWM ART 16162 12, 6, 3, 10, 11, 9 and 4

In the following days, Sargent moved to an American division at Ypres but could not find anything appropriate for his original commission of portraying Anglo-American co-operation. Sargent expressed the frustration of many war artists in finding ‘action’ shots:

The nearer to danger the fewer and the more hidden the men – the more dramatic the situation the more it becomes an empty landscape. The Ministry of Information expects an epic – and how can one do an epic without masses of men? Excepting at night I have only seen three fine subjects with masses of men – one a harrowing sight, a field full of gassed and blindfolded men – another a train of trucks packed with ‘chair a canon’ – and another frequent sight a big road encumbered with troops and traffic, I dare say the latter, combining British and Americans, is the best thing to do, if it can be prevented from looking like going to the Derby.[xvi]

Sargent did suggest such a road scene to the BWMC with American troops and British artillery going up to the line and British wounded returning on the other side of the road. In November 1918 a member of the BWMC, possibly Yockney, wrote to Muirhead Bone noting that Sargent ‘fears this is rather an illustrated paper kind of subject and would not do it on a large scale.’[xvii]

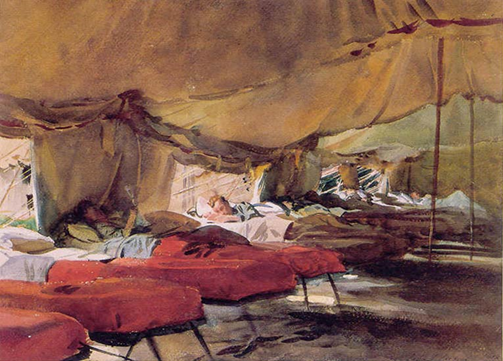

In late September 1918, Sargent contracted influenza and was admitted to 41 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). CCSs were the antecedents of MASH units, hospitals that moved to where action was expected or was taking place. CCSs were each able to cater for about a thousand casualties and were the first well-equipped medical facility a wounded soldier would encounter. Sargent was put into a bed in a wet and uncomfortable tent with the aftermath of battle surrounding him. He was accompanied by ‘dying and wounded men, the nights disturbed by the incessant coughing and choking of the gas victims’ (Figure 5).[xviii] No doubt, this experience gave him knowledge of the consequences of being exposed to mustard gas and helped him empathize with the gassed troops he had seen at Le Bac-du-Sud. By the end of October 1918, Sargent was back in England and working on Gassed which was submitted to the Royal Academy for their 1919 Summer Exhibition.[xix]

Figure 5. John Singer Sargent. The Interior of a Hospital Tent.

Courtesy IWM © IWM ART 1611

Gassed

Gassed is an oil on canvas painting measuring 611.1 by 231 centimetres. It is dominated by a frieze of ten blinded soldiers, nearly life size, being led by a medical orderly towards a marquee indicated by guy ropes towards the right hand edge of the canvas (Figure 1). The accuracy of Sargent’s portrayal of gas victims awaiting further care after initial treatment can be seen in the photograph of gas victims of the 55 West Lancashire Division on April 10, 1918 at an aid station near Bethune (Figure 6). They had been blinded in a German gas attack during the Lys offensive. In 1920, the Observer published a short article on Sargent’s Gassed including a letter by Captain Batten of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Figure 6. 55 Division Gas Casualties, 10 April 1918.

Photograph by 2 Lieutenant Thomas Keith Aitken. Courtesy IWM © IWM Q11586

Batten wrote:

Mr. Sargent’s picture, I saw in life almost exactly as it is painted … These men, as any soldier who saw the later stages of war will tell you, are suffering from ‘mustard gas’ poisoning. The gas was sent out in shells and hung about towns and cellars and dug-outs for an indefinite time. It was not unpleasant to breathe and produced no immediate effects unless the gas shell burst within a yard or two, but those who lived in the gas-infected air for some time became poisoned by it often without knowing what had happened. The symptoms began six or eight hours after exposure to gas and in moderately severe cases started with redness and soreness of the eyes, followed by swelling of the eyelids which could not be opened. The men in the picture were probably gassed twelve hours previously; the whole thing has been gradual – there has been no moment of excitement and distress, as they did in fact arrive at main dressing stations exactly as they are shown in the picture – blind, suffering more or less severe pain in the eyes, unable in their blindness to move anywhere unguided, infinitely pathetic.[xx]

The art historian, Sue Malvern, identifies Gassed as being painted in a classical three-part format, the foreground representing sufferers and sinners, the middle ground redemption or being saved, and the background heaven and salvation. She wrote ‘The foreground displays the war’s victims, all legible to the viewer as whole and unmutilated bodies.’

Figure 7. John Singer Sargent, Gassed.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, IWM Art 001460

These men dissect the edge of the painting suggesting that Sargent is inviting viewers subconsciously into the painting (Figure 7).[xxi] She points out that these distressed blinded victims are jumbled in various poses reminiscent of a Roman sculptural frieze; they form a predella, a decorative panel below a painting or carving often supporting or expanding the narrative. The fear of these men imprisoned in their own minds by bandaged eyes can be imagined. By this stage of the war, soldiers knew that mustard gas casualties suffered blindness a few hours after exposure and this led inevitably to unrelenting vomiting and choking, large skin blisters and, for the most severely affected, death in between two days and several weeks. Some 124,702 British soldiers were gas victims during the war and 2,308 died. Overall 1,250,000 men were gassed on both sides.[xxii]

These men know their pain will increase as they ponder upon whether they may be in the unlucky percentage that will die. By 1918 death in gas attacks had been reduced to three per cent and ninety-three per cent of gas casualties were returned to duty, mostly within a month, but the short term pain was intense.[xxiii] Laura Brandon repeats a common misconception that Sargent has included ‘bodies of the dead’ in the canvas; others have suggested that these men have been heartlessly abandoned to die. However, there are no red tags on these soldiers. Red tags indicated soldiers that were beyond saving; they were transferred to a moribund ward to be bathed and sedated until they inevitably died.[xxiv] These men have probably been triaged and judged fit to be transported to more secure and better equipped medical facilities, such as a CCS.

The middle ground, Malvern’s redemption, dominates the work and she noted that here ‘… there is a frieze of soldiers … processing towards a point of narrative resolution just beyond the edge of the frame.’[xxv] A struggling medical orderly leads the ten blinded soldiers towards a reception tent signified by guy ropes; no doubt they hope this is the beginning of the end of their pain and their eventual salvation. They are highlighted by the setting sun. This projects them against the evening sky. The orderly turns to either warn the followers of a step where duckboards begin or simply to see what was happening.

Richard Cork, the art historian and critic, thought that they ‘struggle forward like some stoical re-enactment of the sightless tottering towards calamity’ in Bruegel’s The Parable of the Blind.[xxvi] In Bruegel’s work, despite the calm landscape and the nearby church, nobody helps the miserable wild looking men, so they help one another; the leader inevitably falls into a muddy stream and drags his companions down into the murky waters. James Shaw, a signaller with the 106 Siege Battery recalled being in a cellar with colleagues as gas and high explosive shells burst above, the smell of gas permeating the air. The following morning as they bathed in a nearby stream, their eyes began to hurt and they decided to walk to a nearby dressing station. They set off but were soon all blind with their eyes and throats causing agony but they continued arm in arm stumbling about the roadway, finding the dressing station more out of a sense of direction than by actually seeing the place.

However, the soldiers in Sargent’s work are being helped, their bodies establish a ‘powerful processional rhythm’ emphasized by the manner in which they link together, hands on the shoulder or equipment strap of the one in front, even their rifles add to the pattern.[xxvii] It is possible that Sargent deliberately drew ‘on the religious associations of the processional form to give his painting spiritual weight and meaning’. Some commentators point out the parallel between the tent guy ropes and the ropes used to raise the crosses in Tintoretto’s The Crucifixion; hence the marquee, off canvas, can be seen as confirming Malvern’s narrative resolution, a place of healing and salvation. Charteris provides evidence of Sargent visiting The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice, several times where The Crucifixion is installed. He notes that letters to friends and relatives indicate that Tintoretto remained ‘one of the supreme masters of painting’ for Sargent throughout his life.[xxviii] Close examination of The Crucifixion reveals that the most prominent ropes lead to the cross on Jesus’ right, his own cross already firmly embedded in the ground, this is commonly thought to be the repentant thief (Luke 23: 40-43).[xxix] A further train of eight soldiers approaches obliquely on the right guided by two orderlies, one supporting a soldier. In the background is ‘the football match and the encampment, all suffused in the warm glow of sunset.’[xxx] The bell-tented encampment is probably the living quarters of the medical facility staff. Sargent has removed the landscape details; the location of this harrowing event could be anywhere allowing the viewer to focus on the narrative.

However, Professor Tonks, mentions diverting to a dressing station at Le Bac-du-Sud and further research clearly identifies the VI Corps Main Dressing Station (CMDS) as being at Le Bac-du-Sud, in the immediate vicinity of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery of the same name. The medical facilities were located on the other side of the road from the cemetery, the N25 running between Arras and Doullens, about 1.14 kilometres west of Le Bac-du-Sud hamlet.[xxxi] Malvern’s salvation, the background, is painted in a restrained cool palette and the soft blue and pink tones produce the warm glow of sunset. To the right the full moon rises into the evening sky indicating it is around sunset as the full moon rises as the sun sets. According to NASA, this was at 18:56 on August 21, 1918 at Le Bac-du-Sud. Sargent must have been facing east, towards the distant battlefield, as the moon rises in the east. Traditionally, it has been thought that Sargent painted the setting sun but if this was the case the lines of soldiers would be silhouettes; instead their sides facing the viewer are well lit and detailed, the sun is behind the viewer. In the distance biplanes are interspersed with anti-aircraft shell bursts; most air battles occurred over the front lines as aircraft photographed or strafed and the opposition air force and army tried to prevent them completing their missions.

Sunset is important for both veterans and the British public. For Great War veterans it was a time to stand-to, a time of increased danger from snipers as the British lines were silhouetted by the setting sun behind them. For the general public, lines from Laurence Binyon’s poem For the Fallen, ‘At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them’ have a symbolic resonance having become ‘a way of maintaining respectful remembrance at a distant point in time’.[xxxii] Before the painting underwent significant cleaning and conservation work in 2022-2023, discoloured varnish made the background yellowish and murky; seemingly Sargent had recorded deteriorating visibility at lower levels as the sun set, the air cooling allowing water and gas vapour to condense, the gas awaiting tomorrow’s victims. The full moon, opaque atmosphere and aerial fighting perhaps imbuing the sky with menace, threatening damnation rather than delivering salvation, evenings bringing on the hell of the night as gas symptoms are magnified in the quiet. However, the restoration prior to the painting being hung in the new Blavatnik Art, Film and Photography Galleries of the IWM has revealed Sargent painted the distant background in cool blues and pinks, a fine clear evening contrasting with the sightlessness of the soldiers.

Article Copyright of Iain Adams

Read Part 2 – HERE

References to Part 1

[i] Nigel Viney, Images of Wartime: British Art and Artists of World War I (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1991); The Royal Academy of Arts, The Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts 1919: The One Hundred and Fifty-First (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1919); Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011, https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk.

[ii] ‘The Royal Academy: A First Notice’, The Times, May 3, 1919, 15.

[iii] Imperial War Museum (IWM). Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Account 2011-2012 (London: The Stationary Office, 2012), 62; IWM, Art Gallery: Breakthrough, http://www.iwm.org.uk/exhibitions/art-galleries.

[iv] Carter Radcliff, John Singer Sargent (New York: Artabras, 1990), 24; Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1927), 13.

[v] John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Frances Sherborne Ridley Watts, 1877, Oil on Canvas, 105.9 x 81.3 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/58933.

[vi] Charteris, John Sargent, 59.

[vii] Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond, eds., Sargent (London: Tate Gallery, 1998), 102.

[viii]Charteris, John Sargent.

[ix] Sargent to Evan Charteris, July 25, 1916, in Charteris, John Sargent, 207.

[x] IWM, How the British Government Sponsored the Arts in the First World War, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-the-british-government-sponsored-the-arts-in-the-first-world-war.

[xi] Paul Gough, A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War (Bristol: Sansom, 2010), 26; Sue Malvern, Modern Art, Britain and the Great War (London: Yale University Press, 2004), 81.

[xii] Alfred Yockney to Sargent, April 26, 1918, ‘John Sargent 1918-1924’, Archive 284A-7 First World War Artists, IWM; Yockney to Bone, October 10, 1918, Lloyd George to Sargent, May 16, 1918., Archive 39/2 part 1 First World War Artists, IWM; Henry Tonks to Yockney, March 19, 1920, ‘Henry Tonks’, Archive ART/WA/329, IWM.

[xiii] Viney, Images of Wartime.

[xiv] War Diary, ‘2 Div., 99 Infantry Brigade: Headquarters, Appendix 1’, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond (TNA), WO 95/1370.

[xv] Tonks to Yockney.

[xvi] Sargent to Charteris, September 11, 1918, in Charteris, John Sargent, 214.

[xvii] Unsigned (Yockney?) to Bone, November 5, 1918, ‘John Sargent 1918-1924’, Archive 284A-7 First World War Artists.

[xviii] Sargent to Mrs Gardner, n.d., in Charteris, John Sargent, 216.

[xix] Charteris, John Sargent.

[xx] ‘Gassed’, the Observer, January 11, 1920, 11.

[xxi] Malvern, Modern Art, 105.

[xxii] James Harris, ‘Gassed’, Archives of General Psychiatry 62, no. 1 (2005), 15; William Moore, Gas Attack: Chemical Warfare 1915-1918 and afterwards (London: Leo Cooper, 1987).

[xxiii] Gough, A Terrible Beauty, 200; Moore, Gas Attack.

[xxiv] Laura Brandon, Art and War (London: I.B. Taurus & Co., 2012).

[xxv] Malvern, Modern Art, 105.

[xxvi] Richard Cork, A Bitter Truth: Avant-Garde Art and the Great War (London: Yale University Press, 1994), 221.

[xxvii] Harris, ‘Gassed’, 16.

[xxviii]Kilmurray and Ormond, Sargent, 265; Charteris, John Sargent, 18.

[xxix] Research visit to The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, August 5, 2012.

[xxx] Malvern, Modern Art, 105.

[xxxi] Tonks to Yockney; War Diary, ‘Deputy Director of Medical Services’ (DDMS), TNA, WO 95/790/3 1; Ordnance Survey and War Office, Map Sheet 51C SE Edition No.2C. TNA, WO 297/3571.

[xxxii] Malvern, Modern Art, 100.