Please cite this article as:

Day, D. Jerry Jim’s Training Stable in Early Victorian Preston, In Day, D. (ed), Pedestrianism (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2014), 57-77.

______________________________________________________________

Jerry Jim’s Training Stable in Early Victorian Preston

Dave Day

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

As sporting opportunities expanded during the late eighteenth century, a number of individuals discovered the possibility of making their living as trainers and coaches. Such men generally emerged from within the activity as retired performers used the knowledge and practical skills that they had garnered during their own competitive lifetime to fashion a career training other sportsmen as well as developing and rationalizing the sports they were associated with. These individuals operated as social beings within a social milieu and successful practitioners were those who proved capable of adapting their behaviours to meet the unique demands of their environment. Trainers shared information with trusted confidantes and, when athletes became coaches, they perpetuated traditional practices, drawing on the knowledge and social networks developed while in training. Every individual’s credibility was subsequently based on a combination of their personal achievements, their age and experience, the competitive success of their athletes, and the respect given them by other leading trainers.

In most cases, training knowledge was embedded within communities of practice, informal structures which continually regenerated as individuals left and they were replaced by new practitioners. For Victorian coaches the communities they generated and sustained were at the heart of their working lives and the knowledge they developed, both separately and together, enabled their athletes to become the elite performers of their generation. Throughout the nineteenth century most of these training communities remained small and locally based and, although industrialization and urbanization, together with scientific and technological advances, facilitated the potential for change in all aspects of Victorian culture, training practices remained distinguished by continuity, although the amateur ethos impacted here as elsewhere in sport. In the latter stages of the nineteenth century, these localized training communities came under pressure as mounting class differentiation within British sport led to a rejection of professionals by elite sections of the middle class who employed structural definitions to exclude trainers when formulating rules for their sporting associations.

Before the formation of these National Governing Bodies the organization of sport relied heavily on the activities of individuals. Professional coaching cultures, acting through tightly connected communities of practice, grew out of a form of cottage industry led by local experts whose knowledge was transmitted orally, or through demonstrated practice, and whose methods were perpetuated, in turn, by their close confidants. This has been shown in work on swimming[1] and it was no different in athletics where local men acted as matchmakers, stakeholders, referees, timekeepers and trainers. Not surprisingly, given their social status, written details of their lives and careers are limited even though levels of literacy among this artisan group were probably quite high. As a result, little trace remains of the majority of nineteenth-century professional coaches just as documentary records of tradesmen and artisans are sparse compared with the biographic records of the elite. This chapter attempts to illuminate one of those lost lives and place that life in the sporting context of the period. James Parker, known as ‘Jerry Jim’ or ‘Jerry Jem’, whose training was ‘not to be surpassed by any professional of the present day’, had a well-established training headquarters in Preston in the North West of England by 1851 where at one point he had nine pedestrians in his stable, a number of them living with their trainer.

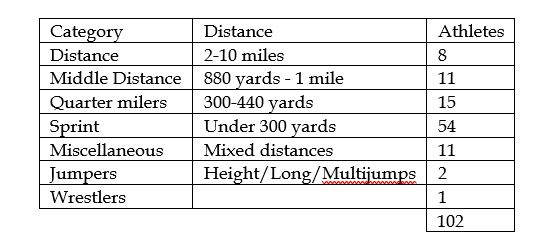

Table 1. Jerry Jim’s athletes by distance run (Bell’s Life)

Analysis of Bells Life reports from the 1840s to the 1860s suggests that Parker trained over 100 pedestrians during the course of his career, many of whom went on to become trainers themselves, an integral feature of coaching communities.[2]

Parker as organizer and trainer

The 1841 census for New Hall Lane, Preston, recorded James Parker as a grocer, aged thirty-five, although he was being described as a beer seller by 1861.[3] There is some limited evidence that Parker was an athlete in his early days with Lawrence Eccles challenging a James Parker, alias Jerry Jem, of New Preston to a two-mile steeplechase over Fullwood Moor in 1842.[4] What is much more obvious from the sporting records is the role that Parker played in organizing the sport and arranging races. His premises at New Hall Lane were a focal point for the depositing of stake money for pedestrian matches from at least 1841, when John Berry issued challenges over 150 yards for £5 or £10 per side, with the money being made available at Parker’s. This form of engagement with the sport continued for more than twenty years with matches being made and stakes being deposited,[5] and, on a number of occasions, Parker acted in unison with equally respected contemporaries such as stakeholder and pedestrian official, James Holden of Manchester.[6] In October 1849, for example, when John Portlock issued challenges for races over 150 yards, matches could be made by sending £2 to Holden of the White Lion, Long Millgate, Manchester, or John Jennison of Bellevue, Manchester, with articles being deposited at James Parker’s premises in New Hall Lane, Preston.[7] Throughout his career, Parker’s involvement extended beyond matchmaking and stakeholding to include officiating. In a man against horse event in Manchester in 1853, he was appointed to officiate as starter, and when Halsall and Barnes were matched to run 150 yards at Preston in December 1859, Parker was both stakeholder and referee, a regular role for him, as was that of timekeeper. Parker also acted more directly as a promoter of events, offering £5 for a 160 yards handicap at the Preston Borough Race Ground in January 1862.[8]

When these grounds had opened on Saturday 23 April 1859, the inaugural 150 yards handicap was refereed by James Parker, alias ‘Jerry Jem’, described in the press as the ‘celebrated trainer’.[9] Jerry’s role as an organizer and official was always secondary to his role as a trainer and from the late 1840s until his death in 1871 his skill was widely and appreciatively reported. Before J. Leigh took on George Hope over 120 yards on Saturday 27 January 1849 at Bellevue he had trained with Jerry, the ‘huge retailer of heavy wet’, who brought him to the ground in fine condition. The competitors bet all their running gear on their own performances and Jerry supposedly ‘lost two or three stone in weight in five seconds’ when Hope won by four yards.[10] Although Roberts, the ‘Ruthin Stag’, had previously achieved some significant performances with hardly any training he was put under the strict tuition of Jerry, the ‘Preston Falstaff’, who ‘did ample justice to him’, before his 120 yards race with Walker in February 1849. Roberts paid close attention to his training regime with Parker, who had trained both men, believing that he was at least three yards better over this distance than Walker. The pedestrians were in ‘apple pie order’ and blooming with health but, despite strict instructions from his trainer not to look around on any account, Roberts turned his head about nine yards from home and Walker passed him to win by half a yard.[11] When Roberts prepared in March for his £100 match over 140 yards against Major Smith, who had been kept to a strict diet and exercise regime by Horsfall of Audenshaw, he trained again at Jerry’s ‘nursery’ and he,

…never entered a racing ground in better order. His eyes bright, skin clear, tread firm, yet as elastic as gutta percha, strong, without an ounce of superfluous flesh, wind good, confidence all right, and spirits as blythe as a lark.[12]

As with pugilists in the eighteenth century, observers of pedestrian events judged the effectiveness of the training period by the appearance of the men on the start line. The ‘ceremony of peeling’ or stripping before a race gave spectators and punters the opportunity to assess an athlete’s condition before laying their bets. When Flockton, whose supporters were mainly from the ‘intelligent class of first-rate mechanics’, raced Smith over 250 yards at Bellevue in 1848 he had a cheerful look, was extremely confident and he had never seemed better. He was ‘fresh as a new blown rose, right colour under the ear, and the safest index of prime condition, an eye clear, sparkling, bright and full of life’. He walked the course in company with the ‘Preston Falstaff’, in a suit of cord, the insignia of ‘his order’, and both men paraded the turf at length whilst the full ‘pot’ was put on, Flockton wearing a light coloured handkerchief around his head and taking an occasional draught out of his ‘much abused bottle’. His skin resembled that of the ‘fairest lily’ and he won by three yards with the stakes being collected at Holden’s premises that evening.[13] When Elijah Phillips (the ‘Prophet’) trained under the ‘ponderous wing’ of Jerry for his 120 yards race against John Clark (‘Metal’) he could not have been in finer condition. His skin, eye, gait, and ‘tol-lol sort of air’ made his supporters vow it was ‘chips to shavings that he could win’. After fourteen attempts, Elijah gained a yard and a half at the start and seemed to have the race under control when his drawers came unfastened as they neared home. As he dropped his hands to hold them up, Clark passed him to win by half a yard.[14]

Despite looking in the ‘primest twig imaginable’, Leigh lost over 120 yards in April 1849 to Ashworth of Manchester whose condition could not have been improved after having trained under that ‘experienced old general, James Parker, better known in sporting society as Jerry Jem’. Reports noted that Parker had brought his protégé to the ground as ‘fine as a star, blooming as a rose, blythe as a lark and lively as a kitten’. Ashworth flew away from the start and won by two yards, receiving the stakes from Holden later that evening.[15] W. Edmundson beat Malpas over 440 yards in 53 seconds for £15 a side in June 1850 after training with Jerry, who was very pleased at his success although he had apparently never entertained any doubts.[16] At Bellevue in October 1852, Blackburn runners Bullon and Pomfret raced over 125 yards having dead heated five weeks previously. The race excited considerable interest and demonstrated what good training could achieve since if two men were equal in age and ability, as these men were, any outstanding performance could only have been the result of the training they had undergone and the way in which their diet had been supervised. Every effort was made to get money on the event, each side being confident about the result, and, in one or two cases, clothes such as coats were offered as stakes. The condition of both men was faultless but the general view was that the ‘palm of superiority’ should be ceded to Bullon because he had undergone the skilful treatment of the eminent Jerry Jem, whose training appeared to be of the ‘most superior character’, and Bullon won by two yards.[17] Not all Parker’s athletes were so successful. In his two miles race against Daniel Gilbert in January 1853, Henry Richardson, who had been prepared by Jerry at his ‘training quarters on the banks of the Ribble’, ran with ‘tortoise speed’. After he lost by more than 100 yards, Jerry, his ‘popular trainer’ said that he was completely ashamed of him and that he was the ‘worst specimen’ ever submitted to his charge.[18]

In April 1855, John Aspin (alias ‘Nobbler’) beat Henry Livesey over half a mile after experiencing the ‘superior preparation of the leviathan Jerry Jem’ and another Parker athlete, George Stansfield, beat James Holden (Holden’s son) over one mile, resulting in Jerry being complimented for producing two winners in a day. At the Copenhagen Grounds on Saturday 24 November 1859, a 110 yards race between John Pomfret and H. Waring resulted in a win for Pomfret, whose appearance reflected great credit upon the renowned ability of his trainer, the ‘well-known Jerry Jim’.[19] Parker’s reputation was always a significant factor in influencing the betting. When Tubber beat Humphrey over 440 yards in 1851 it was noted that he had not been fancied by the ‘knowing coves’ even though he had had the advantage of so eminent a professional trainer as Jerry.[20] One writer in 1854 observed ‘We have frequently seen amongst pedestrians preference being given to a competitor in consequence of the popularity of his trainer’, a trend that could be seen in the example of George Costegan, who was made favourite for his quarter of a mile race against McCandlish mainly because he had been trained by Jerry.[21] It is also clear that Parker was accorded a great deal of respect for his achievements. At Preston Gardens on Saturday 23 July 1859, nearly 2,000 spectators witnessed a 150 yards race, for £25 a side, between Pomfret and Patrick Kearney. So great was the interest that the crowd burst open a door adjacent to the entrance gate and, though they met considerable resistance, between 200 and 300 people gained free admission. After Kearney, who had been trained by Jerry, won by a couple of yards, the drum and fife band of Preston struck up ‘See, the Conquering Hero comes’. A procession was formed behind the band, which marched to Parker’s home, thereby paying him a ‘well-merited compliment for his successful training and firm adherence to foot-racing for a lengthened series of years’.[22] So renowned was Parker that one trainer, Matson of Delph, was better known in his own locality by the soubriquet of ‘Young Jerry Jim’.[23]

The Jerry Jem ‘stable’

A notable feature of Parker’s approach to training was his use of his premises as a training centre for groups of athletes rather than individuals. Sam Mussabini later noted that nineteenth-century sprinters were ‘kept’ and trained for years before the day arrived when they were backed to win many thousands of pounds and ‘called upon to justify their employer’s judgment, care and patience’.[24] In March 1849, Bartholomew Maguire was sent to Jerry’s ‘athletic boarding-school’ at Preston to have the final polish to his preparations from that ‘modern master of training’ before his 100 yards race with Wood. Jerry sent Maguire out as ‘fresh as a daisy’ his supporters being delighted with his wind and stamina. Wood, who had trained himself at home off ale, bread and cheese, barracked Maguire before the race, to disturb his concentration and to get an advantage at the start, which obviously worked since he won by about six inches. Some doubts were expressed about the genuineness of this race because Maguire had trained where other athletes backed by Wood’s patrons had also prepared for their events. However, because Wood’s system of diet and exercise was peculiarly his own, and his style did not suit ‘burly’ Jerry’s academy, Parker had allowed Maguire to train there instead.[25]

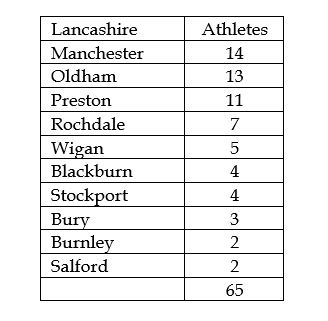

While about sixty per cent of Parker’s known athletes came from Lancashire and its surrounds (see table 2) his stable was also extremely popular with peds from around the country. In preparation for his 880 yards race against Sutton in 1851, William Hind, the Carlisle pedestrian, was sent by his backers to Jerry’s training establishment, ‘in order that nothing which skill and experience could suggest should be lost’. Under Parker’s ‘superior schooling’ he was reported to have done his work well and, because Jerry had invariably been successful, the Carlisle party were confident of victory, although Hind eventually lost by thirty yards.[26]

Table 2. Lancashire athletes trained by Parker (Bell’s Life)

The county police and 6,000 spectators were in attendance at Bellevue on Boxing Day 1851 when Huddersfield man H. Rushworth, trained by Jerry, who ‘brought out his man well up to the mark’, raced over 130 yards against G. Armitage and won by three quarters of a yard in about fourteen seconds. According to reports, ‘too much praise cannot be awarded to the leviathan trainer for the condition he brought Rushworth to the scratch’, and his victory over his muscular opponent was widely attributed to this level of expert training. On the same day, Eli Parkin of Huddersfield, trained at Bradford by the renowned Rush, was the favourite in a mile race against Bincliffe, prepared by Jerry, who again brought his athlete to the start in ‘superlative style’. Despite his backers’ confidence, Parkin retired after three quarters of a mile leading one reporter to point out that Jerry’s stable had defeated the joint talent of the trainers Robinson of Newton Moor and Rush of Bradford.[27]

In the 1851 census, taken on the night of 30 March, the enumerator recorded a number of individuals for Jerry’s premises at 10 New Hall Lane, Preston. James Parker, forty-four, a provision dealer, born Leyland, Preston, was accompanied by his wife Jane, aged forty, and sons John, seventeen, a mechanic, James Parker, aged six, and Thomas, aged three. Also present were visitors Joseph Whitehead, twenty-two, gentleman, born in Oldham; John Harris, twenty-one, shoemaker, born in Huddersfield; Joseph Holmes, twenty-three, farmer, born in Hepworth, Yorkshire; George Eastham, twenty-six, gentleman, born in Preston; and John Saville, twenty-three, a mechanic from Oldham. All these men were well-known pedestrians and they joined other prominent members of Jerry’s ‘Stud’, notably John Tetlow of Hollinwood, Preston, and John Fitton (alias ‘Jack O’Dicks’) of Crompton.[28]

Joseph Whitehead

At Bellevue in October 1850, R. Grundy and Joseph Whitehead, alias Clarke, of Oldham raced 160 yards for £25 a side. Clarke’s backers placed him under the mentorship of Jerry (the ‘modern Sir John Falstaff’) who put him wise ‘to a move or two’ and got him into condition to sprint quickly if he chose to. Whitehead ‘bounded away like a mountain deer’ and won by four yards of ‘a linen draper’s measure’.[29] On Monday 6 January 1851, Whitehead, described as a ‘well-made young man’, who was at this point still unbeaten, raced John Portlock over 160 yards for £50 a side at Bellevue. Whitehead had again been trained by his old mentor, the ‘Leviathan Jerry’, who had made his protégé fitting for the occasion and brought him to the scratch as ‘fine as a star’. Clarke showed considerable anxiety to be off, ‘agile as a cat and as springy as India rubber’, but nearly an hour elapsed before a start could be made, Clarke making twenty-three attempts and Portlock making eleven. Eventually, Portlock obtained a slight advantage, which the Oldham ‘crack’ wrested from him to win by eight yards.[30] In April, Whitehead, still unbeaten, raced Collins over 120 yards for £25 a side. He had been at his old quarters with Jerry and came to the scratch as lively and confident as possible. Collins had been trained by Portlock and, although nearly 5ft 10in in height, he was not nearly as impressive as Whitehead. They got off at the fourteenth attempt and the Oldham ‘pet’ won by two yards. Before racing Howard in November, Clarke, who had now trained nine times with Jerry and won on every occasion, again prepared on the banks of the Ribble. The men got away at the sixth attempt with Howard keeping the lead until ten yards from the finish when Clarke made one of the most tremendous rushes ever witnessed and seemed to win although the referee gave it to Howard. One reporter noted that, for his honesty as a pedestrian it would be well for many of his peers to imitate Clarke.[31]

John Harris

At Bellevue on Saturday 2 November 1850, John Harris (alias ‘Cobbler’) of Huddersfield and Dyson of Castle Hill raced 150 and 200 yards at one start, £5 a side each event. The Cobbler was diminutive but very muscular and, because he had been trained by Jerry, he was made a slight favourite. The Cobbler won the first event by three yards and the 200 yards in 23 seconds.[32] In January 1851, again at Bellevue, Harris, now under the alias of the ‘Snob’, raced Thornton of Kirkheaton over 100 yards for £20 a side. Once again, Harris was sent to Jerry for his training and Parker brought him to the scratch in ‘prime twig’. Thornton, who had previously been crippled by an unskilled chiropodist, was placed under the careful eye of Swankey Greaves, the pugilistic trainer, but, although the ‘requisite appliances had been resorted to’, it was believed that he would still be a ‘limper’, making him unfit to run. As a result, the friends of Thornton were keen to delay the race and his trainer offered terms for a postponement, which the supporters of the Cobbler refused, forcing Thornton to run. While Harris had been favourite the visible improvement in Thornton’s condition noted during his ‘going out by practice at the scratch’ (warming up) improved his odds, although the Snob stuck to his task and finally won by three quarters of a yard in just under eleven seconds.[33]

In February, Harris and Edwards of Staleybridge raced 150 yards for £20 a side. Harris was again trained by the ‘burley Jerry Jem’, who, according to one reporter, ‘it is needless to say, brought his protégé fitting for the occasion’. Edwards appeared somewhat weakened following a recent illness, although he had received the professional assistance of Howard of Bradford, and it appears that he was advised to run in a body dress. In the event, Harris won by several yards in a canter.[34] W. Harrison of Hulme and Harris raced over 140 yards for £20 a side in April. Harris, who had now ‘obtained the soubriquet’ of the ‘pocket Hercules’, had been trained by the ‘well-known Falstaff, Jerry Jem’, alongside Joseph Whitehead and his appearance displayed great muscular capabilities. When he was beaten by three yards many of his backers were somewhat unhappy arguing that he had been ‘cooked’ and that he had not done his best.[35]

Joseph Holmes

On Monday 23 September 1850, Joseph Holmes of Hepworth beat James Hinchcliffe (alias ‘Rant’) of Holmfirth over one mile at Hyde Park Sheffield for £25 a side, thereby repeating his victory of 13 May when he was declared the winner after Hinchcliffe had pulled him down near the finish. At this stage, Holmes was twenty-three years old, and being described as a fine muscular young fellow, standing 5ft 10½in and weighing about 11st 1lbs. He had trained at Preston under the care of Jerry, to ‘whom great credit is due since there was not an ounce of extra flesh on him’. Hinchcliffe was twenty-two years old, stood 5ft 7in and weighed about 10st 4lb. He had trained under Amos Boots and he was in excellent condition although one reporter observed that he was probably 10 to 12lbs too heavy for a mile. Shortly before two o’clock, the men proceeded to ‘arrange their toilet’, which was soon completed, and after several canters as warm ups, they went to the post together and got off abreast. Holmes eventually won comfortably, Hinchcliffe having been obviously outpaced right from the start.[36]

John Tetlow

While not staying with Parker on the night of the 1851 census, John Tetlow had been associated with Parker since 1845[37] and before he took on Hayes at Knutsford in 1848, over four miles for 100 sovereigns, he ‘took his breathings’ at Preston under the supervision of Jerry, although, on stripping, it was noted that he looked a little thin. Hayes, who did his training at Oldham under the direction of William Taylor, led at the end of the first mile in 4mins 55seconds. The second mile was 5min 9seconds, the third 5mins 11seconds and Hayes eventually won by a yard and a half in 20mins 15seconds.[38] When Tetlow trained for his mile race against Robert Inwood on Monday 10 March 1850, he did so again with the ‘leviathan Jerry Jem’ who, inevitably, ‘brought him to the scratch in first-rate condition’. Inwood, who had taken his ‘breathings’ under the pedestrian entrepreneur and trainer George Martin, appeared in a condition fit to compete with his formidable opponent. The thirty-year-old Tetlow, who was 5ft 6¾in tall and had been a runner for fourteen years with varied success, arrived the night before the race and stayed at the White Lion accompanied by Jerry. In the event, Inwood gave up ‘dead beat’ and had to be led off the course, being ‘completely bewildered’, so the stakes were handed over to Tetlow that evening at the White Lion in Manchester by Holden, the stakeholder and referee.[39]

Tetlow raced Hayes again over four miles for £200 at Aintree at end of November 1851. Tetlow prepared once more with Jerry, to whom he was ‘greatly attached and who, it is almost superfluous to state, did ample justice to his protégé’. Hayes, for some reason, changed his own mentor to the veteran Ben Hart, assisted by the ‘facetious little Tommy’, of Bolton. Tetlow’s reported speed in a time trial suggested that defeat was unlikely and he appeared confident and as fit as hoped for by his most committed supporters (although it was whispered that he had been off colour for a day or two in the previous week). Holden was mutually agreed to as referee and a clearer on horseback was appointed to make sure the athletes were unimpeded. Both men were on the course about half an hour before starting, occasionally running short lengths to ‘brace their muscles’. Hayes set off at a killing pace and was a hundred yards up by the end of a mile eventually winning in twenty minutes and forty seconds. After the race both men were put to bed at the Sefton Arms. An attempt was made to bully the referee, under the pretext that Tetlow was knocked down and that he had not had sufficient room to pass his opponent, but Holden would not ‘countenance such a get out’, declaring Hayes the winner and giving up the stakes that evening at the White Lion. [40]

From ‘stable’ to trainer

Two of the men living with Parker on the census night in 1851, Eastham and Saville, and others of his athletes, like John Fitton, followed Jerry’s example in becoming trainers themselves after their running careers finished. In fact, many men assumed training duties or engagements while they were still actively competing. In either event, these men used their personal experiences of training with Parker to inform their coaching practice and their passing on of knowledge and skills was typical of the communities that surrounded trainers.

George Eastham

Between 1841 and 1846 George Eastham, the ‘Flying Clogger’ of Preston, issued challenges and arranged sprint matches using Parker’s, New Hall Lane, Preston, where his money was ‘always ready’, as his base.[41] He was also one of the most prominent Northern sprinters to train regularly with Jerry. In February 1844, he trained with the ‘Preston Infant’ for his 220 yards race at Bellevue against Joseph Etchells when the Clogger appeared ‘right and tight’ and full of confidence. After what was described as one of the finest and best contested races ever seen at Bellevue the referee, James Holden, whose impartial conduct during his many years’ experience in pedestrian pursuits and his satisfactory decisions as a judge in upwards of hundred races had ‘gained him so much esteem’, awarded the race to Etchells by six inches. On arriving in Manchester, the Preston party stated that they would take legal action to get their stake back but one reporter advised them to act as honourable losers and pointed out that they could not always expect to win. Eastham later wrote to the stakeholder declaring that the course had been only 207 yards and that while he had passed the tape with his breast Etchells had taken it with his hand. It was his opinion, and that of his umpire and backers, that he had won and he had been ‘much surprised at Mr. Holden’s decision’.[42]

When Eastham faced William Howarth over 200 yards in December 1844, 8,000 spectators were in attendance, including a ‘fair sprinkling of well-trimmed petticoats, a circumstance not uncommon in the Lancashire districts’. ‘Lady’ Jerry had prepared the ‘Clogger’ thoroughly for the event and it was observed that no athlete had ever appeared for a start with more confidence or in finer condition. In fact, he was described as the ‘quintessence of perfection’. The start was protracted for forty-seven minutes during which forty-four false attempts were made and the race would never had started had not the referee signified his intention of resigning his post if there was any further ‘humbugging’. Eastham won in under twenty-two seconds and the Prestonians passed that evening in a ‘merry manner’ in Manchester during the course of which Parker, whose weight was now upwards of 23½ stone, presented the Clogger with a handsome watch, valued at eight guineas, for his ‘upright conduct’ as a pedestrian. Eastham expressed his thanks and hoped that his supporters would always find him ‘true to his time’ at the winning post.[43] Eastham later turned his own hand to training. At Salford Borough Gardens on Saturday 21 October 1854, his protégé, Daniel Lynch, won a 120 yards race against William Atkins, trained by Jerry, by two yards, both men being brought to the scratch in the best possible condition.[44] Eastham, who held the 220 yards record until Hutchens eventually beat it in 1885, died from acute bronchitis at Preston on Tuesday 23 February 1886, aged seventy, and he was subsequently buried in Preston Cemetery.[45]

John Saville

John Saville was one of those athletes who prepared intermittently with Parker and he appeared on a number of occasions in opposition to Jerry’s men. On 30 September 1851, Saville raced Shaw (alias ‘Skewer’) over a quarter of a mile for £50 at Bellevue. Both Oldham men went into training and Skewer was booked as a dead certainty because he had had the advantage of the professional assistance of Jerry, who placed every confidence in the time of his man. However, Saville’s trainer, John Rush of Bradford, had kept quiet about his time and Saville won in 55 seconds. As the reporter pointed out, losers will ‘grumble, right or wrong’, and many ‘ill-natured expressions’ escaped the lips of those who had bet on Skewer but the fact is that Saville turned out better than was anticipated and his trainer on this occasion ‘made them pay the piper’.[46] In February 1852, Saville, trained this time by Tommy Pope of Oldham, ran one mile against Oakley, trained by Jerry. Both Oldham men were brought out with credit to their trainers and ran until they were completely exhausted with Saville winning by about two yards in 4min 46 seconds.[47]

By 1855, Saville had turned to training. Before Thomas Collins (alias ‘Notchell’) of Jumbo raced 150 yards for £25 a side against the youthful William Pearson of Eccles, Collins had taken his breathings under the ‘vigilant inspection of the of the crack pedestrian’ John Saville, now of the Pedestrian Tavern, Oldham. Pearson had had the advantage of the careful training of Jerry, with whom he lived until the Friday previous to the race when, for some unexplained reason, he was suddenly removed by his backers. Each man appeared to exert every nerve and, after one of the best contests seen for some time, Pearson was declared the winner by twelve inches.[48]

John Fitton (‘Jack O’Dicks’)

It is always interesting to note from census returns that few, if any, individuals in this period described themselves as pedestrians or trainers. Lower class athletes could not afford to support themselves while preparing for competition and only when they could be assured of financial gain did the sacrifice of alternative income sources become a viable option. Similarly, professional trainers could only commit themselves fully to the role of ‘trainer’ when they could be guaranteed sufficient financial returns or stability of employment. This is constantly reinforced by census data, particularly in relation to working-class professional sports like pedestrianism. Individuals like John Fitton of Crompton, who raced and trained under the alias ‘Jack O’Dicks’, rarely, if ever, maintained that as their primary occupation in censuses and Fitton consistently gave his occupation as a joiner between 1851 and 1881.[49]

In his early days, Fitton trained himself and proved to be successful against a number of athletes trained by Jerry Jem.[50] Nevertheless, he joined the Preston stable in 1848 and, five years later, he was training others, many of whom also competed against Parker’s athletes.[51] In order that Hancock and Atkins might be put into the best possible condition before their 120 yards race for £25 a side at Bellevue in October 1853, professional trainers were engaged, Hancock going to his old quarters with Jerry and Atkins taking his breathings under the surveillance of Fitton. In terms of condition, the athletes were as well as their friends could possibly wish and, apparently, both camps were equally confident. Although Atkins had won their previous match Hancock was made favourite, the cognoscenti believing that he had much improved in speed and that Atkins’ form had remained stationary. The weather being cold and windy the pedestrians remained in their flannels but nearly an hour and a quarter passed before they got off, at which point Hancock gradually drew away winning the race cleverly by a yard.[52] At Borough Gardens, Salford, on Saturday 22 July 1854, 300 spectators witnessed a 120 yards race between Jonathan Lyons, trained by Fitton, and Atkins, prepared on this occasion by Jerry. Atkins, who got a clear lead, won by four yards and good judges subsequently expressed the opinion that Atkins proved himself by several yards faster than he had been previously thanks to placing himself in the training of this (so-called) ‘John Scott of the North’.[53] This was a honorary title that Parker was especially proud of. Known as ‘The Wizard of the North’, Scott was the preeminent racing trainer of the period. He won a record forty British Classic Races between 1827 and 1863 and in 1853 he became the first to win the English Triple Crown after his colt, West Australian, won the 2,000 Guineas, the Epsom Derby and the St. Leger. When Jerry was an old man he often looked back upon his career as a trainer with considerable satisfaction and he regularly related with pride the time when he had visited the offices of Bell’s Life and he had met Dowling (the then editor), who had styled him as the ‘John Scott of the pedestrian world’.[54]

The ending of an era

By the second half of the nineteenth century, pedestrianism was struggling to resist the advance of middle class athletes and their organizations such as the London Athletic Club, which had evolved from the Mincing Lane Athletic Club in 1866. As early as 1852, one reporter noted, ‘These are truly dog days; foot racing is completely in the shade at Bellevue; quadriceps are in the ascendant with the former patrons of bipeds; a pedestrian match for £25 being now a thing of rare occurrence.’ When a pedestrian race did come off it was quite possible that it would not be decided on its merits.[55] Another recalled that the attendance of the betting fraternity in Manchester on Monday 6 June 1853 reminded him of ‘auld lang syne’ when footracing had been ‘in its zenith’ in Lancashire. The main attraction that day was a mile race for £20 a side between Holden of Bury (better known as ‘Furry’), who had been supervised by James ‘Leggy’ Greaves of Sheffield, and Lindley who prepared on the banks of the Ribble under Jerry. The condition of both peds seemed satisfactory but Lindley gave up 240 yards from the end and Furry walked over the line in 5mins and 30seconds.[56]

The amateur concern about professional sports like pedestrianism was that an obsession with gambling, winning prizes and striving for records would encourage intentional fouls, bribery and the arranging of results in advance. Judging by the available evidence this argument had some justification since competitors and coaches regularly engaged in various forms of deceit, often based on their ‘stable’ of runner, coach and fellow athletes, which acted as a unit for betting purposes. Professional spectator sports also had the potential for disruption and disorder. Coverage of events concerning Parker and his athletes highlights the increasing difficulties experienced by both athletes and event organizers. At Bellevue on Monday 4 March 1849, thousands of spectators were in attendance, a new bar was opened and ticket prices were raised for admission to the stand because the proprietor, John Jennison, wanted to keep it more select than usual. To keep a good course the staff of clearers was increased under the leadership of Jem May, the ‘Salford Apollo’, and Edward ‘Swankey’ Greaves of Sheffield. Admission was ‘thruppence’ with the pedestrians sharing ‘tuppence’ out of that among themselves. The reporter noted that there had never been the ‘same muster of professionals’ upon any foot-race ground in England. There were pedestrians of repute, boxers of various grades, betting men in abundance, ‘legs innumerable, flash men and swell men, mixing with the greatest impudence imaginable amongst men of respectability’ who had been attracted by the programme of events.[57] Praise was recorded for the authorised clearers May, the ‘head ranger’, and Greaves who had kept an ‘admirable course’ especially when the dense mass of spectators who were packed together on the stand rushed almost unthinkingly forward. In doing so, they forced those at the bottom of the stand against the rails, which gave way and sent many headlong to the ground dislocating a number of limbs.[58]

Following his race with Hayes in October 1851, Tetlow wrote to Bells Life to say that he had been warned before the race that if he led at any stage he would be knocked down. In ‘accordance with orders’ he had played a waiting game but when it became obvious that he was passing Hayes some ‘ruffian’ had knocked him down which ‘entirely annihilated my chance of winning’.[59] Before an advertised 120 yards match in 1852 with Brierley, Wrigley trained with Jerry, and both athletes appeared in good condition. After a number of false starts, a group of roughs intervened stating in ‘unmistakeable language’ that if Wrigley attempted to run they would break his legs. It was ultimately arranged that the race should be delayed for a fortnight, with Brierley to receive thirty shillings towards his training expenses.[60] Having disagreed with Jennison at Bellevue, Horrocks and Howard made arrangements with Attenbury of the Borough Gardens, Salford, to share the gate money with him in 1852. Horrocks, who had been trained by Jerry, was in early attendance but Howard failed to appear, apparently being a local public house and clearly not intending to run. After Horrocks ‘ran over’ the course there was uproar with spectators demanding the return of their entrance money. Attenbury initially agreed but, on discovering that large numbers had scaled the walls without paying, he stopped paying out and gave some people a chitty for a pint of ale at the house instead.[61] Before the Hancock and Atkins race in October 1853, there was considerable ‘badinage at the scratch’, which ended in a melee owing to one of the clearers ejecting two or three persons from the inside of the railings. This irritated their friends who attacked the clearers en masse although the assailants did not get off ‘scot free’, receiving quite as much as they gave.[62] At Salford on Monday 5 March 1855, there was an ‘utter want of any regulation for securing a fair contest’ or for the comfort of the spectators. One observer advised the proprietor, Attenbury, to try to keep the course clear in future because the two police officers in attendance were ‘wholly useless from want of nerve and power’ to protect Mr Holden, the referee in attempting to watch the contest so as to give a fair decision. In addition, the fences were broken down and scores of people gained admittance without payment. [63]

Particular suspicions surrounded the honesty of competitors and the projected match over 120 yards between Staffordshire potters Sherratt and Till in late 1846 exemplified these concerns. On Monday 7 September, after Sherratt had been in training at Preston under the eye of Jerry, the race was abandoned because Till’s friends thought it was a ‘cross’. A rumour got abroad that Till had received £20 to lose, although one reporter believed that these fears had originated from some of Till’s associates having laid their money against him because they had found out that he had been unwell and had run a very bad trial the previous day.[64] The rearranged race was due to take place on Monday 19 October near Newcastle-under-Lyme and Sherratt again went to Preston to train with Jerry.[65] Following an exciting race the referee, Boulton Phillips, gave a dead heat but not without a great deal of unpleasantness. Eventually, the match was brought to a satisfactory conclusion in December at Radford, near Stafford. Although Sherratt had been in training at Preston under Parker, once the match was made his backers placed him under the care of Boulton Phillips who brought him to the scratch in the finest possible trim. Time was lost in choosing the referee, James Woollam Cooper, owing to Till’s party being over-cautious in selecting a suitable official, several ‘respectable and disinterested parties being refused’. When they started by the raising of a flag Till bounded off and eventually won by a yard and a half.[66] The sprint race over 100 yards for £10 a side at Bellevue on Saturday 18 October 1851 between James Boothroyd and Joseph Nuttall was fraught with suspicion from the start. Nuttall trained with Jerry, who put him into the best possible trim, but the general view was that the event would not start because Boothroyd had not been squared to lose and Nuttall had been instructed not to leave the scratch on equal terms with his opponent but to keep dodging until dark and thereby achieve a get out. The patience of the spectators was severely taxed in witnessing the shams for a start, many leaving the ground in disgust, but, at length, Nuttall was caught napping. Nuttall’s supporters tried to argue that the referee, John Jennison, did not see the finish but the objection was overruled, and the stakeholder, Holden, handed over the amount to Boothroyd. [67]

The starting in sprint events was a major cause for concern. Ben Roebuck and Friend Hallas were due to run over 100 yards for £20 a side in June 1851 and Roebuck trained for the match with Jerry Jem while Hallas was trained by Greenwood of Kirkheaton. Roebuck’s reputed trial time together with the popularity of his trainer made him the favourite. The start was to be by pull of a handkerchief and pull succeeded pull with Roebuck remaining stationary in possession of the handkerchief, the person deputed failing to pluck it out of his hand. Hallas appeared too eager to be off, starting several times without notice from the puller. The handkerchief was pulled several times but one kept at scratch with the other running out. At last the handkerchief was pulled from the hand of Hallas, Roebuck still retaining his hold. Roebuck was described as having displayed a white feather in the first instance since he had had ample opportunity to get off by the pull of the handkerchief. Finally, Hallas went through the farce of running the ground over to claim the stakes. The referee and starter decided the men should start by report of pistol in the afternoon but Hallas refused. A dispute arose and it was ultimately decided to scratch again the following day.[68] In June 1852, William Hill, trained by Rush of Bradford, beat Ben Roebuck, trained by Jerry, over 150 yards although the referee had already left the ground, his patience exhausted, after over an hour of false starts.[69] Given this lack of regulation, and the increasing dishonesty of pedestrian events from the 1850s onwards, the only surprise is that pedestrianism continued to cling on as a popular working-class activity for as long as it did. In the end, of course, it took the regulation of professional football to finally toll the death knell for the peds.

On Tuesday 31 January, 1871, in his sixty-eighth year, James Parker died at his home in Preston after a short illness, from the effects of an attack of bronchitis. His obituary recalled that he had moved from Leyland into Preston about 1830 or 31, where, having acquired a considerable knowledge of pedestrian matters, he had established himself as a trainer of running men by 1840. His chosen pursuit had prospered and a series of well-timed successes had brought Parker prominently under notice as a skilful trainer. So widely did his reputation extend that men from all parts of the country had been placed in his charge, as many as nine having been collected under his roof at one and the same time. The writer noted that it would take far too much space to record in detail the names of the noted men to whom Parker acted as mentor in the course of his long career. Many of the most celebrated pedestrians as well as Meadowcroft of Ratcliffe, the celebrated wrestler, had all trained under him from time to time. From his unswerving probity and straightforward conduct Parker was at one period in great demand as stakeholder and referee but latterly he had almost entirely declined to act in these capacities. ‘Old Jerry’ as he was familiarly styled, was a man of huge proportions and at one period of his life he weighed upwards of 27 stone. Because of this he was of late years almost entirely confined to his house, locomotion being nearly an impossibility to him, and upon the rare occasions when he consented to act as referee he was obliged to be accommodated with a chair on the course. Parker was buried on Friday 3 February, leaving a widow and two sons, both of whom had achieved repute as pedestrians.[70]

Sons James and Thomas, who later made a career as a ginger beer manufacturer, had inevitably been drawn into the orbit of their father. In an All England novice handicap of 150 yards at Preston Borough Grounds on Saturday 10 September 1859, Parker, the eleven year old ‘son of the celebrated trainer of this town who we think will be heard of another day’, won his heat easily by about eight yards off thirty yards.[71] At the same grounds on Saturday December 21, 1867, in the preliminary heats of a 140 yards handicap, J. Parker (a son of the well-known Jerry Jem) won heat two off two yards start having passed his opponent by half way.[72] On Saturday 3 December 1870, T. Parker and Barwise raced over a mile for £25 a side. Parker enjoyed considerable repute at distances up to a quarter of a mile but this was the first time he had raced over more than 440 yards. Having undertaken careful preparation under the supervision of his father, Jerry Jem, ‘of former training celebrity’, Parker won by twelve yards in 5min 27¼seconds.[73] The sons also proved useful as training partners for Parker’s athletes. On Monday 18 March 1867, at the Borough Race Grounds in Wigan, colliers J. Sharrocks and Thomas Topping raced over 140 yards for £40. Sharrocks trained at Preston under the supervision of the veteran James Parker, ‘well known in Northern sporting circles by the soubriquet of Jerry Jem’, and had the additional advantage of taking his breathings in company with the son of the trainer. Jerry, as usual, ‘fully maintained his prestige’ by bringing his man to scratch in fine condition. Sharrocks won a close race by three-quarters of a yard and ‘may thank his trainer for his success as nothing but condition and pluck enabled him to pull through on this occasion’.[74]

Looking back at Jerry’s career as a trainer the observer can identify many aspects of his world that reflect the importance of communities in the transfer of training knowledge and the continuity of training practices. The practice of organizing stables of athletes and the involvement of both kinship and non-kinship individuals enabled traditional training practices to survive and facilitated the introduction of innovative methods with trainers being able to experiment with new regimes where necessary. Before certification and credentialism this was the primary means of learning how to be a trainer and understanding the processes involved in training athletes.

References

[1] Dave Day, ‘London swimming professors: Victorian craftsmen and aquatic entrepreneurs’, Sport in History 30 no. 1 (2010): 32-54; Dave Day, ‘Kinship and community in Victorian London: the ‘Beckwith Frogs’’, History Workshop Journal 71 no. 1 (2011): 194-218.

[2] Era, December 15, 1850, 4; Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, September 7, 1851, 3; Census Parker 1851 (107/2265).

[3] Census 1841 HO 107/498/3; 1861

[4] Bell’s Life, November 20, 1842.

[5] Bell’s Life, November 28, 1841; November 20, 1842; January 12, 1845; April 15, 1849, 6; February 5, 1854, 7; April 1, 1860, 7; December 15, 1861, 6.

[6] Bell’s Life, July 22, 1855, 7; July 17, 1859, 3.

[7] Bell’s Life, October 21, 1849, 7.

[8] Era, November 13, 1853; Bell’s Life, December 18, 1859, 7; Preston Guardian etc, March 3, 1860, Front Page; Bell’s Life, December 1, 1861, 6; January 19, 1862, 7; January 19, 1862, 7; May 20, 1860, 7; January 19, 1862, 7.

[9] Preston Guardian etc, April 30, 1859; Bell’s Life, May 1, 1859, 7.

[10] Era, February 4, 1849, 5.

[11] Era, February 11, 1849, 5.

[12] Era, March 4, 1849, 5.

[13] Era, July 2, 1848, 4.

[14] Era, August 27, 1848, 6.

[15] Era, April 15, 1849 5; Bell’s Life, April 15, 1849, 6.

[16] Era, June 23, 1850, 6.

[17] Bell’s Life, October 10, 1852, 6; Era, October 10 1852, 6.

[18] Era February 6, 1853, 5.

[19] Bell’s Life, April 15, 1855, 6; December 4, 1859, 7.

[20] Era, July 6, 1851, 6

[21] Era, October 1, 1854, 16; Bell’s Life, October 1, 1854, 6.

[22] Bell’s Life, July 31, 1859, 3.

[23] Bell’s Life, January 2, 1853, 6.

[24] Scipio A. Mussabini, The Complete Athletic Trainer (London: Methuen, 1913), 245-246.

[25] Era, March 4, 1849, 5.

[26] Era, June 23, 1850, 6; Carlisle Journal, September 26, 1851, 2; Bell’s Life, October 5, 1851, 3; Westmoreland Gazette and Kendall Advertiser, October 11, 1851 2.

[27] Bell’s Life, January 4, 1852, 7. Era, January 4, 1852, 4.

[28] Bell’s Life, April 9, 1848, 6.

[29] Era, November 3, 1850, 5.

[30] Era, January 12, 1851, 5; Bell’s Life, January 12, 1851, 6.

[31] Era, April 20, 1851, 6; November 2, 1851, 5.

[32] Era, November 10, 1850, 6.

[33] Era, January 19, 1851, 5.

[34] Era, February 23, 1851, 5.

[35] Era, April 20, 1851, 6.

[36] Nottinghamshire Guardian, September 26, 1850, 8; Bell’s Life, September 29, 1850, 7.

[37] Bell’s Life, October 12, 1845, 8; January 25, 1846; February 15, 1846, 7; April 5, 1846, 6.

[38] Era, April 30, 1848, 5.

[39] Era, March 16, 1851, 6; Bell’s Life, March 16, 1851, 7.

[40] Era, October 5, 1851, 5; Bell’s Life, October 5, 1851, 3.

[41] Bell’s Life, November 21, 1841; February 13, 1842; June 12, 1842; July 17, 1842; August 21, 1842; March 12, 1843; May 7, 1843; January 14, 1844; April 13, 1845; July 26, 1846, 7; November 8, 1846, 7.

[42] Bell’s Life, February 18, 1844.

[43] Bell’s Life, December 8, 1844.

[44] Bell’s Life, October 29, 1854, 7; Era, October 29, 1854, 5.

[45] Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, February 27, 1886, 7; Bell’s Life, February 27, 1886, 3.

[46] Era, September 7, 1851, 12; Bell’s Life, September 7, 1851, 3.

[47] Bell’s Life, February 29, 1852, 7.

[48] Bell’s Life, March 11, 1855, 6; Era, March 11, 1855, 13.

[49] Census 1851 – HO 107/2243 Crompton Holy Trinity Chapel, Oldham, Shaw New Road – John Fitton, 35, Joiner, born Crompton; Jane, Wife, 35, Domestic Duties, plus Maria, John and Susannah; Census 1861 – RG9/3036 Crompton Shaw Chapel, Shaw New Road – John Fitton, 45, Joiner; Jane, Wife, 45, plus Richard, Maria, John and Susannah and grandson Joseph. All born in Compton; Census 1871 – RG10/4111 Crompton Shaw Chapel, Shaw New Road – John Fitton, 55, Joiner; Jane, Wife, 54, plus Emily Hanson granddaughter, born in Compton; Census 1881 – RG11/4094 Royton, Oldham, St Mark, 464 Shaw Road – John Fitton, 66, Retired Joiner, Jane, Wife, 65, plus Emily Hanson 14 granddaughter cotton operative.

[50] Bell’s Life, September 19, 1847, 7; October 31, 1847, 7.

[51] Bell’s Life, September 4, 1853, 7; Era, September 4 1853, 6; October 23, 1853, 6.

[52] Era, October 23, 1853, 6.

[53] Era, July 30, 1854, 7; Bell’s Life, July 30, 1854, 6.

[54] Bell’s Life, February 11, 1871, 5; James Parker 67 Preston 8e 376.

[55] Era, July 25, 1852, 6.

[56] Era, June 12, 1853, 6.

[57] Era, March 4, 1849, 5.

[58] Era, February 11, 1849, 5.

[59] Bell’s Life, October 5, 1851, 3.

[60] Era, July 25, 1852, 6.

[61] Era, April 4, 1852, 5.

[62] Era, October 23, 1853, 6.

[63] Bell’s Life, March 11, 1855, 6; Era, March 11, 1855, 13.

[64] Bell’s Life, September 13, 1846, 7.

[65] Era, October 18, 1846, 11.

[66] Bell’s Life, December 6, 1846, 6; Era, December 6, 1846, 5.

[67] Era, October 26, 1851, 6.

[68] Bell’s Life, July 6, 1851, 7; Era, July 6, 1851, 6.

[69] Bell’s Life, June 13, 1852, 7.

[70] Bell’s Life, February 11, 1871, 5; James Parker 67 Preston 8e 376.

[71] Bell’s Life, September 18, 1859, 7.

[72] Bell’s Life, December 28, 1867, 6.

[73] Bell’s Life, December 10, 1870, 5.

[74] Bell’s Life, March 23, 1867, 7.