Please cite this article as:

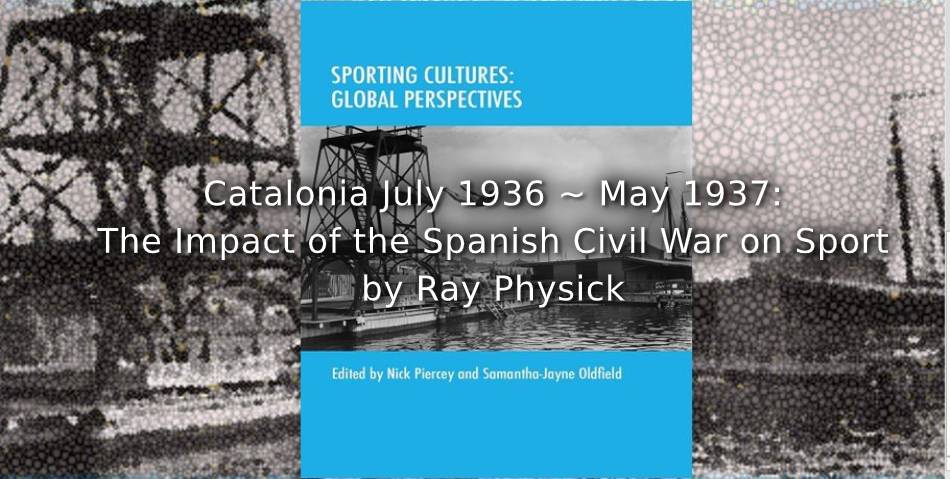

Physick, K. Catalonia July 1936 – May 1937: The Impact of the Spanish Civil War on Sport, In Piercey, N. and Oldfield, S.J. (ed), Sporting Cultures: Global Perspectives (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2019), 84-105.

ISBN paperback 978-1-910029-49-7

Chapter 5

______________________________________________________________

Catalonia July 1936 – May 1937: The Impact of the Spanish Civil War on Sport

Ray Physick

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

The Second Spanish Republic was established in April 1931 when the king of Spain, Alfonso XIII, was forced to abdicate following regional elections that gave republican parties control of Spain’s major cities. From the outset, the Republic suffered from acute political instability that culminated in the fascist-led rising of the July 17 and 18, 1936. Although, the Republic maintained control of the major cities and ports, fascism did obtain a significant foothold, particularly around the area north of Madrid. This situation resulted in civil war, a war that lasted nigh on three years. To complicate the situation, within the Republican Zone but particularly in Catalonia, political parties had different perspectives as to how to defeat fascism. Broadly put, the anarchists and the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, POUM) favoured social revolution as the best means for winning the war. In contrast, the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Party, PSOE), the Partido Comunista de España (Spanish Communist Party, PCE), and other republican parties, favoured a policy of coalition government, known as the Popular Front, which focused on winning the war first and postponing the revolution until after fascism was defeated.[1] This division was reflected in sport and culture, particularly in Catalonia. Initially, sporting and cultural festivals were held in support of the revolution. Gradually, the PCE perspective on the war became dominant; the outcome for sport and culture was that it came under the increasing scrutiny of the state.

The fascist-led military rising, which reached mainland Spain on July 18, 1936, had a profound impact upon sport within the Republican Zone. The rising resulted in major street battles in Barcelona, a situation that forced the cancellation of the Olimpiada Popular (Popular Olympics), scheduled to open in the city on July 19. Generally speaking, active sport throughout the Republican Zone was paralysed following the military rising.[2] Following the defeat of the rising, however, a new social and political situation emerged, particularly within Catalonia where a full-scale social revolution occurred: the widespread collectivisation of industry reflected this revolution. Overall, it is estimated that 70 percent of industry was collectivised in Catalonia. Moreover, public order was largely in the hands of the militias, armed bodies that came under the control of the Catalonia Anti-Fascist Militias Committee (CAMC). The dominant force on this body was the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour, CNT), the anarchist union that had a mass base in Catalonia. A dual power situation emerged in Catalonia with the authority of the Catalonian government, which was led by the president of Catalonia, Lluís Companys, being severely compromised by the revolutionary powers inherent in the CAMC.[3] The weakness of the government was recognised by Companys, who summoned the revolutionaries to the Generalitat Palace telling them that: ‘[y]ou are masters of the town and of Catalonia, because you defeated the Fascist soldiers on your own…You have won and everything is in your power’.[4] Companys went on to say that, if needed, he would use his ‘name and prestige’ to assist them in the struggle against fascism. The leadership of the CNT acquiesced to Companys’ offer even though ‘real power was held by the armed workers and the organisation committees in the streets of Barcelona…’[5] Lacking a revolutionary strategy, the leaders of the CNT, in contrast to the rank-and-file of the workers’ militias, vacillated, showed magnanimity to Companys who formed a de facto coalition, Popular Front, government, which also included the then relatively small unified Catalan Communist Party, the Partit Socialista Unificat de Catalunya (Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia, PSUC).[6] Parallel to these events, a new national Popular Front government, was established in Madrid under the leadership of the socialist Largo Caballero, on September 4, 1936. During his premiership the social and political influence of the PCE grew immeasurably throughout the Republican Zone. This situation was mirrored in Catalonia where the PSUC also became a very powerful political force. Moreover, its presence became increasingly felt in sport. Lastly, it is also important to note the geographical situation in relation to the warfront. Compared to Madrid, for example, Barcelona was, initially, surrounded by Republican territory with secure land and full access to the sea.[7] This favourable situation enabled sporting events to be organised in Catalonia without the immediate threat of military attack.

It is in this context that this chapter will assess the significance and the changing nature of sport within Catalonia, particularly in Barcelona, during the revolutionary period, between July 1936 and May 1937. Research into the period is hampered by the lack of extant records. Newspaper records are often incomplete while records of club committee meetings exist only in fragmentary form.[8] The Barcelona-based sports paper, El Mundo Deportivo, is a vital source and extensive use of its archive has been made. Academic research regarding sport and the Civil War is also limited. The work of Xavier Pujadas Martí is an exception to this generalisation: this chapter extends his work with a fuller assessment of the political situation, and its impact upon sport within Catalonia between July 1936 and May 1937. The extensive volume by the Spanish journalist Julián García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil has provided a broad overview with regard to sport during the period.

The re-emergence of sporting events

When sporting events re-emerged from late July onwards, they were often organised to support the militias, politically as well as financially. Indeed, many events were organised with the authority of the CAMC. Sporting events were also organised in support of the Hospitales de Sangre, to provide the medical means required to treat those injured in the early months of the Civil War.[9] Moreover, sport was not immune from the collectivisation process that swept Catalonia following the rising. Many football clubs were brought under workers’ control, including the region’s two La Liga clubs, FC Barcelona and CD Español.[10] Also, footballers, boxers, cyclists, among other deportistas, formed unions, and in some cases governing bodies, with a view to having more control over their respective sports.[11] Even football referees established a Comité de Incautación del Colegio de Arbitros Profesionales (Workers’ Committee of Professional Referees), with aim of having more control over their profession.[12] This revolutionary change in the structure of sport began to be undermined following the dissolution of the CAMC during September 1936 and the reestablishment of the authority of the Generalitat, which in turn came under the increasing influence of the PSUC. In the initial period, following the defeat of the rising, sporting festivals, reminiscent of the cultural events that occurred in the early years of the Soviet Union, were organised on a regular basis, often spontaneously.[13] According to Pujadas, between August and December 1936 there were 37 football, three swimming, three cycling and three basketball festivals. In addition, there were regular sporting events for boxing, cycling, motorsports, tennis and rugby. In total there were at least 52 solidarity sporting events (actos solidarios) in Catalonia in this period.[14] However, the changing nature of the war, with the Republic progressively losing ground to Franco’s armies, changed the political situation within the whole of Republican Spain. The Republic became increasingly dependent upon military aid from the Soviet Union; this in turn empowered the PCE and the PSUC. The foreign policy of Stalin in this period favoured alliances with the bourgeois democracies of Britain and France, hence its support for the Popular Front government, a coalition that included both worker and bourgeois parties. The process of collectivisation that swept Spain, in the weeks following the defeat of the fascist rising was halted and eventually went into reverse, following the establishment of the Caballero Government: this process was accelerated under the Negrín Government, which was formed in May 1937 following the May Days debacle in Catalonia.[15] The May Days debacle resulted in defeat for the CNT and the POUM, the former organisation was politically emasculated while the latter was supressed, and led to the empowerment of the PCE/PSUC. In effect, the revolutionary period came to an end after the defeat of the May Days rising. From then onwards, the state assumed evermore central control as the independent workers’ committees were suppressed. This view is confirmed by Angel Smith:

After the May Days the central state quickly took control of the war effort, and workers’ committees were replaced by organs of state power…after the May Days at the telephone exchange – where the fighting had started – the anarchist colours were lowered and in their place was hoisted the Catalan flag.[16]

The aims of the war, which had initially been linked to securing the revolution, also changed. The stated aim was now one of winning the war first and establishing a stable Popular Front government, that would be acceptable to the capitalist countries of France and Britain. The political and military situation impacted upon cultural expression, following a decree by the Commissariat for Education and Sport on November 21, sporting spectaculars declined dramatically. Indeed, as the political grip of the PSUC strengthened in Catalonia, sport became less spontaneous and more focused on immediate aims such as supporting refugees, the injured and the displaced.[17] Gradually, spontaneous cultural expression was supressed, as the PSUC extended its political influence, and increasingly reflected the cultural situation in the Soviet Union of the 1930s.[18] Eventually, sport became more militarised, the outcome being that the number of sporting festivals fell to just eight in 1937.[19] To highlight these differences, a comparison will be made between the sporting events that took place to commemorate La Diada de Catalunya (National Day of Catalonia) with a sporting festival of March 21, 1937, held under the auspices of the Front de la Joventut, the de facto youth wing of the PSUC.

La Diada de Catalunya – September 11, 1936

La Diada, the national day of Catalonia, commemorates the fall of Barcelona in 1714 during the War of Spanish Succession. Following the fall of the monarchy in April 1931 Catalonia established its own autonomous government, the Generalitat, within the Spanish Republic. The birth of the Second Republic ushered in a new era of cultural development throughout Spain; culture in effect became a vehicle for social communication. Lorca’s La Barraca, for example, took travelling theatre groups into areas of Spain that hitherto had had no access to live theatre. Likewise, sport developed in this new socio-political period, a situation clearly illustrated in Barcelona where, between 1931 and 1936, 241 new sports clubs were registered compared with 140 between 1925 and 1931.[20] Prior to July 1936, there was a fusion of culture and sport that expressed itself in mass street cultural celebrations to mark the national day and sport played its part in developing a sense of national identity within Catalonia.[21] The preparations for the Olimpiada Popular further raised cultural awareness among the population of Catalonia. For example, a full-scale athletics and swimming programme was held at Montjuïc, the Olympic standard sports complex located near the city centre, on June 29.[22] Moreover, an exhibition of art at the Palacio de Arte Moderno at Montjuïc also formed part of the Olimpiada cultural celebrations: over 40 artists from various artistic disciplines submitted work for the exhibition. The cultural side of the Olimpiada Popular was overseen by Victor Gassol, who was the Minister for Culture in the Catalan Government.[23] Also, a run-through of the opening ceremony, which featured specially commissioned music by Hans Eisler, was held at Montjuïc, in front of a large crowd, on the evening of July 18, demonstrating the carnivalesque atmosphere that had built up around the Olimpiada.[24]

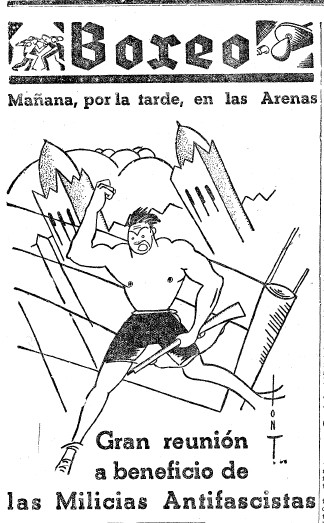

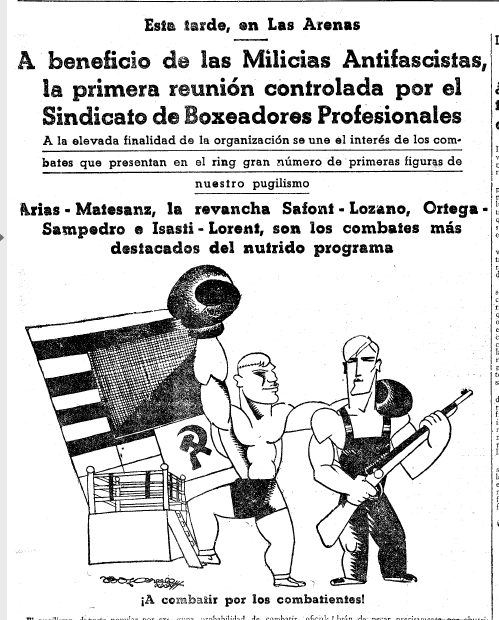

Once the rising had been defeated the mood of celebration returned. The ‘popular revolution’ gave cultural expression to this and was used as a ‘legitimising weapon’ against ‘those social classes that for centuries had controlled all branches of political power and culture’.[25] Sport was an integral part of this cultural expression. This became evident prior to La Diada. For example, on August 23 there were at least 12 football matches held within Barcelona and district, all were well attended. The Europa v Barcelona match, held at the Campo del Europa, was attended by militiamen, who saluted, with raised fists, the large crowd, thereby reinforcing the symbolic association of sport with the struggle for liberty and against fascism.[26] To reinforce this point, 25 percent of all gate monies went to supporting the militias.[27] Football, being a mass spectator sport, was at the forefront in raising money to support the CAMC. On the same day, however, other sports, including swimming, cycling, basketball and rugby, organised festivals in support of the militias and the Hospitales de Sangre. Photographs reproduced in El Mundo Deportivo show that all events attracted large crowds. Moreover, amateur sporting bodies organised festivals of sport in support of the same organisations. For example, la secció Esportiva del Centre Autonomista de Dependents del Comerç i de la Indústria (Professional Trade Union Association CADCI), one of the organisations behind the Olimpiada, held a day long multifaceted sports day, which included athletics, cycling, basketball, rugby and football, in the neighbourhood of Barcelona La Bordeta.[28] Boxers and boxing were also strong supporters of the revolution. Throughout August El Mundo Deportivo reported on boxers joining the militias, several of whom were killed or injured. Boxing’s support for the revolution led to the formation of the Sindicato de Boxeadores Profesionales (Union of Professional Boxers) on August 23. This body, which consisted of managers as well as boxers, affiliated to the CNT, and took control of boxing events from the promoters.[29] One such boxing promotion held at Las Arenas, the bullring located near Montjuïc, on September 5, attracted a sell-out crowd. During the evening boxers who had fought at the front were presented to the cheering crowd.[30] Reports from the previous two days in El Mundo Deportivo also carried two cartoons that clearly associated the boxing promotion with the cause of the militias.

Both cartoons (Figure 1 and Figure 2) clearly illustrate that sport was firmly behind the militias and that sportsmen and women were prepared to support the fight to defeat fascism. Figure 2 is captioned: ‘¡A combatir por los combatientes!’ or ‘to fight for the combatants’. The boxer clearly identifies with the militiaman who is distinguished from a regular soldier by his dungarees, the symbolic uniform of the revolution in Catalonia. This situation was reinforced in the four days of cultural celebrations to commemorate La Diada, celebrations that were intended to show that an alternative to fascism was not only possible, but that a new social and political order was also achievable. According to García Candau, the events were extraordinary, and sport was at the forefront of the celebrations.[31]

- Figure 1. A cartoon of boxer in support of the militia.[32]

- Figure 2. A combatir por los combatientes![33]

Following the celebrations around La Diada, El Mundo Deportivo carried an editorial which declared that ‘sport represents the flag of peace and fraternal human existence’. However, the editorial continued, ‘when freedom is in jeopardy athletes must use their body strength to defend it even if it means flying the flag of war’.[34] Such contrasting emotions can be found in the parades, as well as in the sporting events that contributed to the celebrations around La Diada. At a meeting on September 8, the Comité Catalán pro-Deporte Popular (Catalan Committee for Popular Sport, CCEP) encouraged all sports clubs to participate in the celebrations around La Diada. The object of their involvement was to honour the victims of fascism.[35] Symbolically, this was carried out on the eve of La Diada at the Rafael Casanova monument where flowers, flags and standards were laid in honour of the martyrs of 1714. The association with the struggle against fascism was evident at the commemoration with flags from political parties, cultural organisations, including sports clubs, prominently laid around the monument.[36]

La Diada began with a mass parade through the streets of Barcelona followed by speeches by president Companys, the mayor of Barcelona and a representative from the CCMA. The sports section of the parade was headed by the CCEP, closely followed by the Club de Natación Barcelona (Swimming Club of Barcelona). Photographs from El Mundo Deportivo clearly show that these sections were made up of men and women.[37] Also, prominent on the parade were sections representing Barcelona’s La Liga clubs. The workers’ committee of FC Barcelona encouraged its players, members and sympathisers to form a ‘column’ to pay ‘homage’ to those ‘martyrs’ who fight for our ‘liberty’. [38] Likewise, the workers’ committee of CD Español encouraged its members to support the parade under the club flag. Following the parade cyclists gathered in Parque de la Ciudadela, from where a road race through the streets of Barcelona commenced. Prominent among the riders was the Spanish champion Mariano Cañardo, indicating once again that leading deportistas were to the fore in supporting the Republic. The day ended with a concert in Parque de la Ciudadela given by the Banda de Milicias (The Militias’ Band); included in their repertoire were music and poems from the opening ceremony from the abandoned Olimpiada Popular. Cultural expression associated with La Diada was clearly interlaced with the cause of liberty, which in the early period of the Civil War was linked to the support of the militias who were clearly fighting, not only against fascism, but for the social revolution that had engulfed Catalonia. The Valencian cyclist, Salvador Molina, speaking before the race, made the position of the riders crystal clear, they were taking part in the road race both in support of the militias, ‘who are fighting for the liberty of workers and in defence of the socialist republic’.[39] The following two days were also filled with sporting events in honour of the militias. On September 12, there was a swimming festival held at Montjuïc in support of the victims of fascism. At the Montjuïc stadium there was a full athletics programme and cycling events. Other sports such as basketball, rugby and boxing also held events in support of the militias. The festivities closed the following day with a football match, also held at Montjuïc, between the city’s two La Liga clubs, which was won by CD Español.[40] Prior to the match, the sports clubs that had taken part in festivities, paraded around the cinder track to great acclaim from the large crowd.

Internationally, a football team from Catalonia played a team representing British trade unions with the match being held in Paris at the Stade Pershing on September 13, 1936. The game was part of a sports day held in support of the Spanish militias and their struggle for ‘liberty and democracy’; it was attended by 15,000 spectators drawn mainly from the French labour movement.[41] In subsequent years, reflecting a changed political situation within the Republican Zone, La Diada was dominated by speakers from the PSUC and Esquerra Republicana de Catalynua, with little cultural import to embellish the commemoration.[42]

Workers’ Committees and Deportistas: taking control – incautación[43]

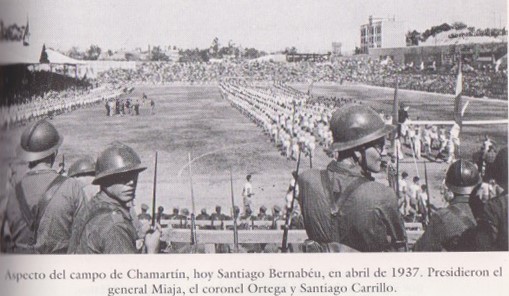

One of the most remarkable features of the Spanish Civil War was the speed and scope of the collectivisation process. As indicated above, sport was not immune from this development; sports governing bodies and clubs were taken over by workers’ committees throughout the Republican Zone. Both of Madrid’s La Liga clubs, for example, were taken over and run by a workers’ committee, or a comité de incautación. The FC Madrid committee was made up of representatives from the La Federación Cultural Deportiva Obrera (Worker Sport Federation of Spain, FCDO), pro-republican parties, trade unions and socios (club members).[44] At its inaugural meeting the committee agreed to make the facilities of the club available, according to the secretary Pablo Hernández Coronado, ‘to all those who are heroically defending the democratic Republic against fascism’.[45] Furthermore, when the Batallón Deportivo (Sport Batallion) was formed in September 1936, the committee made Charmartín, the club’s stadium, available for military drill. The idea to form a Batallón Deportivo emerged out of the Federación Castellena de Fútbol (Spanish Football Federation), which was also controlled by a comité de incautación. It was the view of the committee that a Batallón Deportivo would provide physically strong athletes who would, in turn, improve the performance of the militias at the front.[46] The Batallón Deportivo undertook exercises and military drill at Charmartín, Hernández Coronado was of particular importance as he became the physical advisor to the battalion.[47] It named its first company after FC Barcelona’s president Josep Sunyol, who was summarily executed by Falangist troops in the Guardarrama mountains on the August 6, 1936.[48] At Charmartín on September 27, a match between the Batallón Deportivo and Athletic de Madrid, in support of orphaned children, was held with the Batallón Deportivo winning 2-0 with goals from Pablito and Trinchant. Demonstrating the importance of the role of worker organisations to the Republic the crowd sang songs associated with the Spanish and international labour movement.[49] The Batallón Deportivo team included players from FC Madrid. A photograph (Figure 3) of a sporting spectacle held at Charmartín, from April 1937, clearly shows that the regular army became heavily associated with sporting events in Madrid. The leading personnel mentioned in the caption were all associated with the PCE and were instrumental in forcing the militias into the regular army, which in turn played a key role in securing the policy of winning the war first and abandoning the revolutionary gains of collectivisation. In this sense, the Batallón Deportivo was a body that came to represent the militarisation of sport. A development that will be explored further below.

Another major outcome of the revolutionary response to the military rising of July 1936, was the rapid establishment of trade unions within professional sport. Despite their clubs being run by workers’ committees professional footballers in Barcelona formed the Sindicato de Profesionales del Fútbol (Professional Footballers Union, SPF), which affiliated to the Unión General de Trabajadores (General Workers’ Union UGT), in August 1936.[50] Among the players’ demands was the scrapping of the retain and transfer contracts with players demanding the freedom to negotiate their terms of employment collectively.[51] Demands that, in theory but not in practice, were conceded by both of Barcelona’s La Liga clubs. The aims of the players were made clear by the secretary of the newly formed union, Domingo Carulla:

Figure 3. A sporting spectacle held at Charmartín, April 1937

When a player signs for a club, the contract will be controlled by the union and thus avoid the tricks that undermine the good faith of a professional who signs for a salary of three hundred pesetas a month and when a disagreement arises in the contract, he receives a salary of twenty-five pesetas a week…We will have to review contracts and settle pending disputes between players and clubs.[52]

While the demands of the players were generally accepted wider events impacted upon the clubs’ ability to fully implement such contracts. The main problem was that La Liga was suspended during the Civil War. Substitute Catalan and Mediterranean leagues were formed, but revenue from these matches, even though attendances were good in the inaugural season, was insufficient to sustain a club such as FC Barcelona. Hence, in the spring of 1937, when the club was invited to tour Mexico to play a series of matches, they readily accepted. The tour was financed by basketball player, turned businessman, Manuel Soriano. He offered the club US$15,000 in cash upfront plus another US$8,000 deposited in the pro-Republican Spanish consulate in Mexico City. 16 players plus Barcelona coach Patrick O’Connell, a former captain of Ireland, and the Secretary Robert Calvet left Spain for Mexico in June, the tour lasted until September 1937. At the end of the tour, Robert Calvet, the club secretary, called a meeting of the touring party. He outlined the deteriorating situation in Spain and gave them the choice, of either returning to Spain, where they faced an uncertain future, or going into exile. Of the 16 players, 7 chose to go back to Barcelona along with Calvet, O’Connell and Mur the team doctor. Overall the tour made a profit of US$12,000 for the club with Calvet depositing the money in a Paris bank account.[53] The most significant factor, however, facing the returnees was the worsening refugee crisis in Barcelona and the deterioration of the military situation throughout the Republican Zone.

The re-establishment of the State and its impact upon sport

As indicated above, the fascist rising in Barcelona, and in the surrounding towns and villages, was defeated by the CNT and POUM militias; the POUM was particularly strong in Catalonia. Another decisive factor was that both the Guardia Civil and Guardia de Asaltos, who fought alongside the militias, were in effect incorporated into them.[54] It was in this context that Companys offered his help, but his main aim was to derail the revolution, stabilise the situation and safeguard what was left of private property. The fact remains, however, that the militias had significant power, the power to take control relatively peacefully, as the repressive organs of the state had been smashed: ‘Many have described the resulting situation as one of dual power, with the Anti-fascist Committee exercising real power while the government of the Generalitat still existed in name’.[55]

A similar power vacuum could also be found in Madrid, where Martínez Barrio, who served as Prime Minister for less than a day in July 1936, noted that: ‘Not a single soldier could be seen…The absence of the coercive organs of the state was manifest,’ with the power vacuum being filled once again by armed workers’ militias.[56] Even the PCE leader, Dolores Ibárruri, had to acknowledge that ‘the whole state apparatus was destroyed and power lay in the street’.[57]

What both the CNT and the POUM did not fully grasp was that dual power is an either-or situation: two power forces, one nascent, the other residing with the established government, contending for power:

Two powers really did exist. One of them, that corresponding to the workers, had the strength but not the will to rule; the other, the petty-bourgeois republican force, lacked strength, but possessed a clear will to recover power.[58]

Procrastination by the CNT and the POUM enabled Companys to effectively ensure ‘a continuity of state power even if it was temporarily in the background’.[59]

Following the establishment of the Popular Front government in Catalonia, it was no coincidence that mass sporting festivals went into decline. Benefit events were still regularly held to aid the victims of fascism, with cycling, athletics and swimming being the most prominent sports. Most of the support was channelled through the Socorro Rojo Internacional (Red Relief International, SRI), a humanitarian aid body that was closely associated with the Communist International and, by association, with the PCE and the PSUC.[60] Given that the Communist parties of Spain were against the militias having independent power it is not surprising that sporting events to raise monies for the militias were redirected to support the injured, refugees and those made homeless by the war. Sporting events came to be a conduit for humanitarian aid, rather than as part of the struggle for liberty. Typical of such events was a swimming festival organised by Club de Natación Barcelona, with the support of the UGT, on December 20, 1936. Moreover, the well-to-do of Barcelona were invited to financially support the event in order to guarantee its success. Among the subscribers was Hans Gámper, one of the founders of FC Barcelona, who was among ‘otros no menos notables’ (other no less notables) who supported the festival financially. Politically, it reflected the dominance of popular frontism, which favoured broad coalitions between parties, whether their ideology was Catalan nationalist, liberal or socialist.[61] Gone were the sporting festivals that were organised with the aim of raising money for the militias with definitive support from parties and unions associated with the Spanish labour movement.

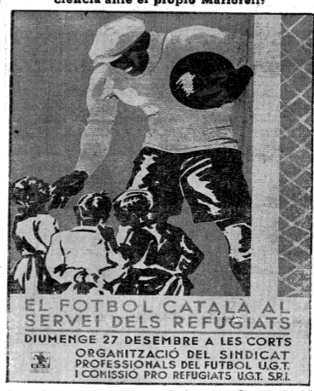

Another example of sport supporting refugees was a football match at Les Corts, the home of FC Barcelona, on December 27, 1936, organised by the SPF in collaboration with the SRI, the UGT and supported by the Russian and Mexican Consuls. In contrast to the first weeks of the Civil War, when Barcelona’s football clubs supported the militias, the benefit match was played with two teams selected from a wide range of players. Les Corts was the venue, but there is no indication that the workers’ committees of FC Barcelona and CD Español were involved in the organisation of the match. Moreover, judging from the photographs of the stadium, attendance at the match was sparse. A spokesperson for the SPF told El Mundo Deportivo that 7-8,000 were in attendance, blaming the lack of interest on public indifference.[62] Compared to the febrile atmosphere of August and September 1936, when sporting events were massively supported this was disappointing; it reflected the changing mood of the population, which was becoming more concerned with the effects of the war upon daily life. The image of the goalkeeper (Figure 4), showing concern for refugee children illustrates this clearly. Earlier photographs, posters and cartoons had the message of, not only of defeating fascism and supporting the militias, but of fighting for liberty, which in the context of Catalonia was support for social revolution.[63]

These two examples reflected that sport and cultural events were becoming less spontaneous and, detached from the influences of the mass of the population, organisationally they became top-down affairs. It also reflected that politically, government was being directed by a strong centralised party, namely the PSUC. In the weeks following the fascist rising, dual power had meant that the political direction of the revolution was being influenced by the rank-and-file workers’ committees, which tried to push the CAMC to seize power.[64] However, rather than strengthen the workers’ committees by co-ordinating them into an alternative government, the leadership of the CAMC ceded their powers to a Popular Front government.[65] Moreover, as the PSUC gained the upper hand politically, sport became more and more associated with a militarised state. According to Pujadas, by the spring of 1938, the militarisation of sport had been achieved.[66] The process towards this state is well illustrated by the aforementioned sports festival organised by the Front de la Joventut, in conjunction with El Mundo Deportivo, on March 21, 1937.

Indeed, prior to the festival, a mass demonstration in support of the ejército popular (popular army) was held in Barcelona. Prominent on the march was the banner of the CCEP, indicating that sports organisations were still proactive in support of the war. However, in contrast to the earlier demonstrations, which linked the struggle against fascism to liberty and socialism, the demands were now limited to the defence of the republic under a single command (mando único), reflecting that a state was being created in the image of the Soviet Union under the dictatorial command of Stalin.[67]

The festival, which was held at Montjuïc, focused on the sporting prowess of the soldiers of the popular army at sport. However, as Figure 5 illustrates, it was sport with a difference, as all the athletic events had a military theme. For example, relays were run with soldiers carrying a rifle, the steeplechase had military obstacles and there was a hand-grenade throwing competition in place of more traditional field events. There were also demonstraciones bélicas (war demonstrations), which included how to attack an enemy trench and how to mount and fire a machine gun blindfolded. There were ‘athletic’ teams from various barracks and a delegation from the Batallón Alpino, but the emphasis was on the militarisation of traditional sporting events. Indeed, El Mundo Deportivo described the event as a great manifestation of military sport.[68]

- Figure 4. An image of a goalkeeper advertising efforts to help refugees. [69]

- Figure 5. A poster advertising the Diada de la Joventut

- Figure 6. A poster advertising the Gran Fesitval Militar Esportiu.

- Figure 7. An image showing the close link between the military and sport.[70]

There was also a football match scheduled between a Catalan eleven and a team from the communist dominated British Workers’ Sports Federation. However, the British team were not granted visas by the Foreign Office, an adjunct of the British Government’s Non-Intervention policy, and was replaced by a team from the French worker sport movement.[71] Figures 6 and 7 serve to reinforce the close association of sport with the military underlined by the ethos of the youth day, which was organised to reinforce the ‘value of sport to military preparation’.[72]

Conclusion

The Spanish Civil War was a highly complex affair. In Catalonia, the response to the fascist rising resulted in a profound social revolution, which initially generated great optimism among the mass of the population. As outlined above, this enthusiasm was reflected in sport, with many sports clubs and deportistas openly displaying their support for the revolution and also open in their support for the militias. However, political deadlock within Catalonia resulted in the empowerment of the PSUC at the expense of the radical unions and parties such as the CNT and the POUM. The profound social change, epitomised by the collectivisation of sport clubs, soon began to unravel. Collectivisation implied a transfer of ownership from former owners to the workers; it was widespread in Barcelona, but also had a significant presence in cities such as Madrid, Valencia, Alicante, Almería and Málaga. However, under Negrín the ‘collectivisation decree was suspended’ enabling the government ‘to take over any metallurgical or mining’ concerns.[73] According to David Cattell, the PCE/PSUC did advocate workers’ control but their concept of it differed radically from the version implemented by the anarchists:

To the Anarchists it was complete control of the factory in every aspect by the workers, but to the Communists it meant workers’ control subject to the orders of the manager and owner and to the over-all direction of the state.[74]

Castells Duran has argued that ‘[t]he experience of the Civil War shows that expropriation by the state does not necessarily have to be directed against the bourgeoisie, but can also be aimed at the workers themselves’.[75] Indeed, under Negrín, who became prime minister in May 1937, former employers were brought back to run the factories thereby increasing the likelihood that a Republican victory would re-establish previous employer/worker relationships. In the eyes of many workers, the war and the revolution were different aspects of the same process: by removing the possibility of a new society based on the workers and the peasants, i.e. socialism, the Republican Government only served to demoralise those in the rearguard. This process also occurred in sport. An example of dashed hopes in sport can be found in the acceptance of amateurism by the SPF in July 1937. Footballers now faced the prospect of receiving match tickets instead of wages, a far cry from their earlier demands for reasonable wages. In this context it is unsurprising that the majority of FC Barcelona players chose to stay in the Americas.[76]

- Figure 8. The Spanish team marching at the 1937 Antwerp Workers Olympics.[77]

At the Workers’ Olympiad, held in Antwerp in July and August 1937, Spain’s team was largely drawn from members of the CCEP, plus a delegation from the Fourth Division of the Republican army, a division that had been fighting on the Andalusian and Aragon fronts. As Figure 8 shows, they marched through Antwerp in front of a banner with the slogan of the Civil War emblazoned on it: No Pasarán (they will not pass). The FCDO statement in support of the Spanish team emphasised that the delegation demonstrated that sport was at the vanguard of the struggle against fascism. A somewhat overblown claim, perhaps, but it serves to reinforce the point made above about the militarisation of sport, which cannot be separated from the militarisation within the Republican Zone.[78] This is demonstrated by the ‘depleted Cortes [which] was now a mere collection of walk-ons, and there was no question of elections…’[79] Real power in the diminishing Republic lay with the army, which in turn was under the tutelage of the PCE/PSUC. Republican Spain had become a de facto military state under which all forms of daily life were subservient to it.

The Republic eventually collapsed in March 1939. The first major sporting event to take place under the fascist regime of General Franco was a football match between FC Barcelona and Athletic Bilbao, held at Les Corts on June 29 1939. The directors’ box was occupied by the president of Barcelona, Joan Solé Julia, and other key fascists such as General Álvarez Arenas. The players lined up in front of the directors to hear pro-fascist speeches. Alongside the Spanish flag were the flags of Spain’s two key allies Germany and Italy. The media described it as a great patriotic sporting event. One sports historian has noted that ‘[a]fter the end of the Civil War, sport became part of the State’s machinery…The ideas, which were going to give meaning to sport, were obedience, submission and military discipline’.[80] In essence a not dissimilar situation had existed in the dying days of the Republic.

References

[1] The POUM was an anti-Stalinist Communist Party often accused, incorrectly, of being Trotskyist. PSOE was the Spanish Socialist Party, the PCE the Spanish Communist Party.

[2] Xavier Pujadas Martí, ‘Entre Estadios y Trincheras. El Deporte y la Guerra Civil en Cataluña, 1936-39’, Universitat Ramon Llull, Barcelona, 1, https://www.cafyd.com/HistDeporte/htm/pdf/1-9.pdf (accessed February 14, 2019). It is important to note that the Olimpiada Popular emerged out of a movement to boycott the Berlin Olympics and became linked with the ethos of the worker sport movement. Preparations for the event also raised the political awareness of the population. The manifesto that was published alongside the sporting programme put forward the idea that sport could contribute to a peaceful world and enhance the progress of humanity.

[3] For an analysis of dual power see Victor Alba and Stephen Schwartz, A History of the POUM in the Spanish Civil War: Spanish Marxism versus Soviet Communism, (New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2009), 117. Companys belonged to Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, the Republican Left of Catalonia.

[4] Pierre Broué, and Emile Témime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008), 130.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The PSUC was, in effect, organically linked to the PCE.

[7] Frances Lannon, The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2013), 32-33.

[8] A point made by Julián García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil (Madrid: Espasa, 2007), 18.

[9] Hospitales de Sangre were field hospitals that provided immediate treatment at the frontline.

[10] The national football league, La Liga, was suspended for the duration of the Civil War. Of the 12 clubs that comprised the league four, were located in Nationalist held areas, Osasuna, Oviedo, Sevilla and Betis. A further two clubs, Athletic Bilbao and Racing Santander were surrounded by areas under fascist control. It should be noted that under the Republic the appellation ‘Real’, for clubs such Real Madrid and Español, was dropped.

[11] I have used Spanish here because it is gender neutral. Deportistas derives from the Spanish word for sport, deporte.

[12] El Mundo Deportivo, September 17, 1936, 1. A Comité de Incautación was in effect a workers’ committee.

[13] For the Soviet Union see James Riordan, ‘Worker Sport within a Worker State: The Soviet Union’, in The Story of the Worker Sport Movement, ed. Arnd Krüger and James Riordan (Leeds: Human Kinetics, 1996), 49. Riordan makes the point that sporting events in the Soviet Union ‘began to be organised from the bottom upwards.’ A similar situation existed in Catalonia in the immediate aftermath of the defeat of the fascist rising.

[14] Pujadas Martí, ‘Entre Estadios y Trincheras’, 3.

[15] For the process of collectivisation see Broué and Témime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain, 150-171 and Antoni Castells Duran, ‘Revolution and Collectivisations in Civil War Barcelona 1936-39’, in Red Barcelona: Social Protest and Labour Mobilisation in the Twentieth Century, ed. Angel Smith (Oxford: Routledge, 2002), 127-141. For a contemporary account of the May Days rising see George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (London: Penguin, 2000).

[16] Angel Smith, ed., ‘European Mirror: From Red and Black to Claret and Blue’, in Red Barcelona: Social Protest and Labour Mobilisation in the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 2014), 11.

[17] By the spring of 1937, there were approximately 350,000 refugees in Barcelona. See Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution and Revenge (London: William Collins, 2016), 253.

[18] For a broader discussion about culture and political power see Alicia Alted, ‘The Republican and Nationalist Wartime Cultural Apparatus’, in Spanish Cultural Studies: An Introduction, ed. Helen Graham and Jo Labanyi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 152-166.

[19] Pujadas Martí, ‘Entre Estadios y Trincheras’, 3.

[20] Xavier Pujadas Martí, ‘De Atletas y Soldados: El Deporte y la Guerra Española en la Retaguardia Republicana, 1936-1939’, Estudios del Hombre 23 (2007): 91-94.

[21] Xavier Pujadas Martí and Carles Santacana, ‘Del Barrio al Estadio. Aspectos del Sociabilidad Deportiva en Cataluyna en la Década de los Años Treinta’, Historia y Fuente Oral 7 (1992): 33.

[22] Ray Physick, ‘The Olimpiada Popular: Barcelona 1936, Sport and Politics in an Age of War, Dictatorship and Revolution’, Sport in History 37, no. 1 (2016): 51-75.

[23] See El Mundo Deportivo, June 27, 1936, 6; André Gounot, ‘El Proyecto de la Olimpiada Popular de Barcelona (1936), entre Comunismo Internacional y Republicanismo Regional’, Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte 1 (2005). Although I have identified the artists who submitted work, to date I have been unable to trace any of the artwork.

[24] El Mundo Deportivo, July 19 1936, 1. Two photographs of the event appear on the front page of the paper. See also Physick, 11-16.

[25] Alted, ‘The Republican and Nationalist Wartime Cultural Apparatus’, 152.

[26] El Mundo Deportivo, August 24, 1936, 1. The caption with the photograph of the militiamen reads: ‘Una sección de milicianos desfiló por el campo del Europa saludando el público con el gesto simbólico de la lucha libertad y contra fascismo…’ (A section of the militias paraded around the stadium of FC Europa greeting the public with the symbolic gesture with the fight for freedom against fascism).

[27] El Mundo Deportivo, August 23, 1936, 1.

[28] El Mundo Deportivo, August 31, 1936, 4.

[29] El Mundo Deportivo, August 24, 1936, 1.

[30] El Mundo Deportivo, September 6, 1936, 1.

[31] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 65-73. In the orginal Spanish, Candau describes the celebrations as follows: ‘El 11 de septiembre, la premier Diada en guerra, se preparó, desde el punto de vista deportivo, como acontecimiento extraordinario’ (On September 11, the first La Diada of the war, extraordinary sporting events were prepared).

[32] Image from El Mundo Deportivo September 4, 1936.

[33] Image from El Mundo Deportivo, September 5, 1936.

[34] El Mundo Deportivo, September 13, 1936, 1.

[35] El Mundo Deportivo, September 9, 1936, 1-4. The CCEP was also integral to the organisation of the Olimpiada Popular.

[36] El Mundo Deportivo, September 12, 1936, 4. Casanova was the Councillor in Chief of Barcelona during the war of the Spanish succession.

[37] El Mundo Deportivo, September 12, 1936, 4.

[38] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 65.

[39] Ibid., 65-68, ‘…va a celebrar una grandiosa carrera el la Capital de Barcelona a beneficio de las milicias que luchan en defensa de la Libertad…dispuesto a hacer el mayor sacrificio en defensa de la República Socialista, que es la libertad de todos trabajadores españoles’ (The great race will be a great celebration, in the capital, Barcelona, in support of the militias who are fighting for liberty…[and are] willing to make big sacrifices for the defence of the Socialist Republic and for the liberty of all Spanish workers). See also reports in El Mundo Deportivo between September 9-12, 1936.

[40] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 68.

[41] El Mundo Deportivo, September 9, 1936, 1; El Mundo Deportivo, September 1, 1936, 1; September 17, 1936, 1; Daily Worker, September 15, 1936, 1.

[42] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 69-70.

[43] Incautación is the term used in the Spanish press to describe the taking over of industry, including sports clubs, by workers’ committees.

[44] The FCDO was the body that represented the worker sport movement in Spain.

[45] El Mundo Deportivo, August 12, 1936, 1. See also Sid Lowe, Fear and Loathing in La Liga: Barcelona vs Real Madrid, (London: Yellow Jersey Press, 2013), 45.

[46] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 79.

[47] Ibid, 82-84; El Mundo Deportivo, September 16, 1936, 1.

[48] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 80; Lowe, Fear and Loathing in La Liga, 28.

[49] García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 84; El Mundo Deportivo, September 27, 1936, 3.

[50] El Mundo Deportivo, August 31 1936, 1.

[51] The retain and transfer system restricted the free movement of players between clubs. It empowered the clubs who could retain a player against his will.

[52] El Mundo Deportivo, September 9, 1936, 1. Carulla played for the successful FC Barcelona team in the 1920s.

[53] Lowe, Fear and Loathing in La Liga, 35; Jimmy Burns, Barça: A People’s Passion (London: Bloomsbury, 1999), 118-120. There are conflicting figures about the number of players who stayed or returned.

[54] Heraldo de Madrid, September 4, 1936. Also, cited in Broué and Témime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain, 130. The Guardia Civil was an armed para-military police, established in the mid-nineteenth century, whose loyalties to the Second Republic were open to question. The Guardia de Asaltos was an urban police established to act as a counterweight to the to the Guardia Civil.

[55] Pelai Pagès i Blanch, War and Revolution in Catalonia, 1936-1939 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014), 37.

[56] Burnett Bolloten, The Grand Camouflage (London: Pall Mall Press, 1968), 30.

[57] Dolores Ibárruri, Speeches and Articles, 1936-38 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1938), 214.

[58] Alba and Schwartz, A History of the POUM in the Spanish Civil War, 118.

[59] Preston, The Spanish Civil War, 236. By its nature a dual power situation is temporary, one power eventually emerges as the dominant force. A similar situation occurred in Russia in 1917 with the Soviets eventually overthrowing the Provisional Government.

[60] Socorro Rojo Internacional undertook similar tasks to the modern-day Red Cross.

[61] See articles in El Mundo Deportivo, December 18-21, 1936. Politically, Gámper was a supporter of Lliga Regionalista, a Catalan nationalist party.

[62] El Mundo Deportivo, December 28, 1936, 1.

[63] El Mundo Deportivo, December 23-28, 1936.

[64] See Agustin Guillamón, Ready for Revolution: The CNT Defence Committees in Barcelona, 1933-38 (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2014).

[65] Agustín Guillamón, ‘Barricades in Barcelona: The CNT from the victory of July 1936 to the necessary defeat of May 1937’. Available at: https://libcom.org/history/barricades-barcelona-cnt-victory-july-1936-necessary-defeat-may-1937-agust%C3%ADn-guillamón.

[66] Pujadas, ‘De Atletas y Soldados’, 113.

[67] El Mundo Deportivo, March 1, 1937, 1. For a contemporary analysis of the Soviet Union see Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed (London: Wellred Books, 2015).

[68] El Mundo Deportivo, March 21, 1937, 2. The Batallón Alpino was in effect a battalion of skiers. Their role, in the Pyrenes and in the mountains around Madrid for example, was to provide a supply chain between the urban and snowbound fronts.

[69] Image from El Mundo Deportivo, December 25, 1936.

[70] Image from El Mundo Deportivo, March 21, 1937.

[71] Daily Worker, March 19, 1937.

[72] El Mundo Deportivo, March 21, 1937, 1.

[73] Broué and Témime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain, 313.

[74] David T. Cattell, Communism and the Spanish Civil War (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1955), 62.

[75] Castells Duran, 139.

[76] El Mundo Deportivo, July 30, 1937, 1.

[77] Image from Programme of the 3rd Worker Olympiad Antwerp, 1937.

[78] See García Candau, El Deporte en la Guerra Civil, 300, who reprints the FCDO statement in Spanish.

[79] Broué and Témime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain, 313. The Cortes was the Spanish Parliament.

[80] Ramón Llopis Goig, ‘Identity, Nation-State and Football in Spain: the Evolution of Nationalist Feelings in Spanish Football’, Soccer and Society 9, no. 1 (2008): 59.