Please cite this article as:

Jenkins, A. Nineteenth Century Foot Racing: The Tyneside Connection, In Day, D. (ed), Pedestrianism (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2014), 149-170.

______________________________________________________________

Nineteenth Century Foot Racing: The Tyneside Connection

Archie Jenkins

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

Tyneside`s sporting history is knee deep in the sport of pedestrianism. The Tyneside example shows how sport and its heroes can play a role in the formation of the cultural identity and self-confidence of a region at a key time in its development. Victorian popular athletics encapsulate several recurrent themes in nineteenth century British sports history. Here is a working class activity taken up by the entertainments industry in the form of the tavern trade; a popular gambling sport, standing in opposition to dominant ideologies and a site of struggle over the social class meanings attached to the amateur and professional. The popularity of pedestrianism as a sport on Victorian Tyneside eventually evolved into twentieth century road running, suggesting it may have had some lasting impact and legacy on modern competitive and popular participation. Following the prominence of North Eastern `peds` in the great long distance walking races of the early nineteenth century emerged foot racing in new enclosed running grounds which attracted a particular class of runner. Tyneside produced two of the most famous names of the time: James Rowan and Jack White. Celebrated local pedestrians and the venues that attracted large crowds will be identified as part of the legacy that would have such an impact on the area.

Pedestrianism on Tyneside

Newcastle and Gateshead were regarded as two of the great centres of pedestrianism during the nineteenth century. Tyneside foot racing, three local nineteenth-century heroes and the venues were all part of the legacy accounting for the popularity and success of middle and long distance running in the North East of England today. In a period of rapid industrial expansion, a cultural revolution took place on Tyneside in which new sports and pastimes helped to foster a new form of regionalism. The importance of sporting pursuits brought forth sporting gladiators. The hero was seen as typical of the region and representative of its skills and strengths, `the pride and determination with which victory is anticipated, furnish true exponents of our Northern character`.[1] London was to be the target for the new North East patriotism. The first regional heroes with whom the working population could identify was fuelled in sporting rivalry served by connections of work and trade between the Tyne and Thames. Economic and industrial development, enabling Newcastle to assume the status of commercial, financial, administrative and cultural capital of the North made Tynesiders aware they could challenge the capital on their own terms. With gambling a common feature of Northern society, runners, promoters and their sponsors were in business in terms of prize money, admissions and large scale betting. The prime benefactor was the tavern trade where the articles of agreement were signed. Both in London and Newcastle large crowds were common for attractive matches, held usually on a Saturday and Monday as well as on public holidays. In the days of running footmen employed by coach companies, Newcastle`s position near some of the key routes would have ensured local participation and the production of keen runners. Pedestrianism as a necessary skill was part and parcel of mining communities where miners were compelled to travel to find work.

From 1904 until 2004 the Morpeth to Newcastle road race was claimed to be the oldest of its kind in Britain. Its roots can be traced back to the nineteenth century and one of the forgotten heroes of local pedestrianism, James Rowan. Rowan used to train on the Great North Turnpike Road between Newcastle and Morpeth in the 1850s, or as stated in the press `on the same track on which the great Jimmy Rowan was wont to train`. In the 1890s Newcastle Harriers decided to commemorate Rowan`s training route when fifteen members took a train to Morpeth one January evening and then ran back in the dark, followed by a horse and cart which carried their overcoats. By Christmas Day 1902 this club training run had evolved into a handicap race and B. Stockdale of Darlington Harriers was the first winner of `the Morpeth`. With some discontent over the handicapping, it was decided to make it a scratch race. The following year the Newcastle Journal provided an annual trophy and the race date was fixed for New Year`s Day, and the first `open` winner was Campbell also from Darlington. For the next one hundred years many famous names were inscribed on the Journal Trophy and the list of illustrious runners failing to win is equally impressive. Winners include national stalwarts Duncan McLeod Wright (six wins), Jim Peters and local legends Jim Alder and Mike McLeod both with five victories. In 2002 due to increased traffic the race was switched to mid-January and, following the centenary run in 2004, the local police authorities pulled the plug on England`s longest surviving road race for safety reasons. This mirrored events some 160 years earlier when a similar ban fell on those who used the same roads for competitive racing.[2] Over the 1844 Christmas period the popularity of this turnpike route outside Morpeth had reached such a peak that the Newcastle magistrates announced their intention to put an end to the practice by imposing fines of forty shillings on anyone taking part. The Saltwell Harriers Christmas open road race, also on Tyneside, beginning in 1911 now claims the title of the oldest road race.[3] The 10k event is held over three laps of the undulating Victorian Saltwell Park. In 1904, South Shields Harriers, based south of the River Tyne, claim to have inaugurated the world`s first harrier team road race from Sunderland to Westoe. Brendan Foster, synonymous with the region`s endurance running success in modern times, relates the success of the Great North Run to the history of North East pedestrianism through an understanding of the local sporting heroes of the past, their role in popular culture and the enormous numbers of spectators who witnessed both.[4]

With pedestrianism including walking as well as running, American Edward Weston`s long distance walk in Newcastle in 1877 sparked off a local craze for walking events. Soon, for a time, the opposite route from Newcastle to Morpeth became the favoured location for walking events organized by the licensees of Newcastle.[5] One walking legacy to follow was the extraordinary thirty-year road and track-racing career from 1906 of Tom Payne, a member of both North Shields Polytechnic Harriers and their rivals South Shields Harriers.[6] Payne`s accomplishments included holding the world non- stop walking record of 127 miles and 543 yards.

Personalities

Three champion pedestrians became part of Geordie sporting folklore, showing the importance sport and its heroes had in forming the cultural identity of a region. As early as 1729 Peter Radford recalls a Geordie runner by the name of Pinwire (Pinwherie) winning 102 races between 1729 and 1733, only two of his results have survived, running ten miles in 52minutes 3seconds in 1733 and 64 minutes in 1738. Pinwire`s performances are likely to have taken place in the Midlands, Warwickshire and Staffordshire.[7] It is not sure if these times were performed naked, as many serious runners of the time were known to participate with no clothes emulating the runners of the ancient Olympics, all possible in the absence of governing bodies.[8]

George Wilson

It was George Wilson however, one of the great professional athletes in the early nineteenth century who was first to achieve local hero status.[9] Radford in describing Wilson as a great new endurance star also portrays him as a `poor, thin man`.[10] Born in Newcastle in 1764, he left school and became an apprentice shoemaker before selling second hand goods, at the same time supplementing his income by collecting taxes and parish rates. Initially he enjoyed this job as it allowed him to indulge in his passion for walking and once, for a dare, he walked from London to Newcastle in four days. The job however earned him the nickname `dog tax` and becoming sick of the unpopularity, he gave up and began peddling books around the country. His penchant for walking soon became legendary and he was employed by a publisher compiling An Itinerary of Britain which meant he had to verify by foot the distance between various points and routes listed in the book. Due to his long absences his wife became unfaithful and his marriage broke up in 1813. In the same year following an unfortunate business relationship with his wife`s uncle he was left penniless and sent to Newcastle`s Newgate debtors gaol.[11] In desperation, to reduce his debt, he put wagers on with other prisoners that he could walk fifty miles in twelve hours. For the small sum of £3 and 1 shilling he undertook the walk within the prison walls. After measuring his small flagged exercise yard at 33` by 25½`, he cornered 10,300 times to make up the distance and accomplished his task with 4mins 43seconds to spare. On his release he returned to selling books but found walking matches more lucrative. Inspired by Captain Barclay`s famous 1809 walk, Wilson who had a flair for showmanship declared his intention to attempt the same distance in twenty days.[12] Rapidly attracting the public`s imagination he commenced his shuffling walk in Blackheath on the 11 September and he soon became known as the Blackheath pedestrian. Blackheath turned into a carnival and the vast crowds soon became unruly. With victory in sight on the sixteenth day he was arrested for disturbing the peace and walking for remuneration. In his defence in his own memoirs he states `I had no connection with the tumblers, rope-dancers, fire-eaters, conjurers, pony-racers, cutlers, gin-sellers, gingerbread merchants, ballad singers or other purveyors of amusement or luxury who crowded Blackheath for a whole fortnight.`[13] A further and more detailed publication by the unfortunate pedestrian followed. John Laurens Bicknell follows this up in a legal discussion reviewing not only Wilson but previous cases concerning pedestrians and examines the law and magistrate`s attitude to pedestrians of the past.[14] Despite his failure and arrest, the interest of the press magnified Wilson`s popularity. In 1815 he published his own autobiography, possibly the first ever athlete to do so, yet the book is little concerned with athletics and relates more to his exploits, the woes of his life and his failures and was an attempt to recoup some of his losses. He sold thousands of his own pictures, continued racing and made numerous appearances at theatres in his walking kit. Before retiring from his public exhibitions, he proposed to display his feats of endurance in Newcastle for the honour and entertainment of his native town by covering ninety miles in 24 hours. On Easter Monday 1822, on the Town Moor racecourse, in front of a crowd estimated at 40,000, Wilson covered the ninety miles with fourteen minutes to spare. Here was a hero for all Tyneside and he was duly carried off in style.[15] He then addressed the crowd with an impromptu speech appealing for donations. However as a result of the miserly contributions he gave up in disgust and according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography disappeared completely from public notice and his death is recorded as in or after 1822.[16] However the Newcastle Courant on the 15 May 1824 reports a G. Wilson walking 150 miles in 48 hours, on Durham race course, within ten minutes of the stipulated time.[17] Once again the voluntary subscription of the spectators was described as trifling. Wilson`s efforts encouraged others and Newcastle`s Robert Russell`s covered 101 miles in 23h 56mins on the Town Moor in July a few months after Wilson`s efforts which inspired a song in the Tyne songster.[18]

Wilson, desist! And Simpson, take your rest!

Ease and retirement now will suit you best

Your brief excursions will excite no more

That admiration which they did before;

Though doubtless ye have both endeavour`d hard,

Perhaps without an adequate reward;

But such laborious journies lay aside,

And if ye can, instead of walking, ride.

‘Hide your diminish`d heads!’ nor vainly talk,

Among your friends, how rapidly you walk:

First in the annals of Pedestrian fame,

Historians now will enter Russell`s name;

Where he will most conspicuously shine,

And long be hail`d The Hero of the Tyne.

Upon this art he has so much refin`d,

That he leaves all competitors behind.

With buoyant step we`ve seen him tread the plain,

And hope, ere long, to see him walk again.

Another song relates to Simpson the Pedestrian`s Failure. John Simpson was a Cumberland pedestrian who failed twice within weeks over the same distance on the Town Moor, firstly at Whit and then he was soundly beaten by Russell in July.

Up to 1828, contests were chiefly matches against time, but the sporting men of the day soon decided to match pedestrians in head to heads. Riorden `the Flying Potter`, Atkinson `the Coal Boy` and Scarlett `the Doctor` brought fresh impetus to local foot racing. Early national handicaps however got little press coverage in the Tyneside sporting intelligence pages but a good performance by a local man did warrant a little more and the first to come to notice were two Gateshead born runners James Rowan and John White. They did more than anyone to stimulate local interest in the sport and their prominence left their marks in pedestrian history. Like the famous Tyne rowers they attracted thousands to their races and played their own part in the Tyne versus Thames rivalry. Regional newspapers indicate Rowan entered more races at home, especially in his early career and being trained locally by James Hogg, noted for his stable of Tyneside pedestrians, possibly made him the most popular. Ned Corvan included a verse about them in his 1862 `Wor Tyneside Champions` and arguments raged to who was the better. Corvan was to bring the whole image of regional patriotism down to earth.

`Of runners te, we`ve got the tips

Tyne bangs the world for pacin

Gox! White and Rowan champion peds

Bangs a the lot for racin

When little White means runnin lads

He`s shaped in fine condishin

He dodg`d to get the start like this

See graceful in position.`

-

Figure 1. Wilson as he appeared on the morning of the ninth day of his walk

(Grosvenor Prints)

James Rowan

James Rowan was described as a popular, colourful, humorous, selfish showman but, importantly, a class athlete.[19] Publicity was vital in pedestrianism, and running in black shorts he was known as the Black Callant, (callant a Scottish term for a little laddie).[20] He was, however, his own worst enemy. Fame and glory catapulted him into the heady world of money, sex and greed and he was abused by unscrupulous bookies. Like many others who have emerged from a working-class background, he was struck by fame and although known as keen trainer gave himself up to the highlife. Rowan was born in Dunston Street in Gateshead in 1835, the fourth oldest of six children, the son of a local cobbler also James (mother Ann) and his world was the slums of Gateshead. Immediately, a comparison with another of Gateshead`s wayward sons Paul Gascoigne born coincidentally in the working-class Dunston area springs to mind. Small in stature he soon realized he had a talent for running. Realizing his ability he cast his humdrum life aside and became a Victorian superstar. His first recorded races were in 1854 and he ran many matches up to 1¾ miles against local pedestrians before travelling the country to compete against the best of the day over a variety of distances from 100 yards to ten miles. By 19 he had won a handicap race in Ayrshire, advertised as the ten mile championship of the world. His first appearance in London in 1858 ended in defeat and despite winning three ten mile champions cups, the six mile champion`s belt and setting the three mile British best he had an unhappy association with the capital. On numerous occasions he withdrew from races or failed to turn up without explanation, with drink often to blame, with his having the reputation as a thirsty soul. Stan Long, coach to Brendan Foster, described Rowan as `Gateshead`s own black assassin who guzzled more post race beers than his wee 104 pound body could tolerate.[21] The Sporting Telegraph covers one of celebrations in the White Lion at Hackney Wick famous for its hospitality before and after pedestrian matches, `the cup was presented to Rowan with all due honours, the health of the winner and loser being enthusiastically drunk, and the meeting did not adjourn until a late hour`.[22] In 1860, Rowan stayed, as usual, in London`s Wellington Inn before a challenge by his fellow Geordie Jack White, on his non appearance at the last minute, the large London crowd were quick to blame his drinking.

Rowan received astronomical amounts of money to race and, in his prime, such was his fascination and ability he could attract thousands of spectators. The Era in 1860 describes his style `although he runs with high action, Rowan is nevertheless a smart, active, and graceful runner`.[23] The consummate showman, he would stop halfway through a race and play to the crowd or drink from a bottle of whisky. Flushed with success, Rowan succumbed to those who fed his ego and surrounded himself with predatory hangers on and as a result pressed the self destruct button. Against the background of the looming American Civil War he achieved some fame across the Atlantic, before being duped by wealthy manipulators. In a race against Deerfoot, he refused to throw the race and was physically beaten up. His running career was soon in decline. He was abandoned in America and pride forgotten he was forced to earn his passage home by running against animals as a circus performer.

On returning to Gateshead he found Bella the love of his life happily married and his old dedicated coach James Hogg now distant with a life of his own. After losing his last race at Hackney Wick in 1862, little was heard of him again and searching for solace through the bottom of a glass, a common failing among pedestrians. He died of consumption in Gateshead aged 27, not long after a benefit had been held for him by James Baum at the White Lion in Hackney Wick. Unwanted he was interred in a pauper`s grave in St. Edmunds Cemetery, Gateshead. Upwards of 100 sporting celebrities attended and walked in procession to the graveside including local rowing champions Robert Chambers and Bob Cooper. Numbers of the running fraternity from London and several provincial towns were also present.[24] This is in comparison to the 100,000 who attended rower James Renforth`s funeral when he was buried in the same graveyard in 1871. The press reported `during his championship career he was regarded with the utmost confidence by his friends but unfortunately he became unsteady and was soon surpassed by others`. None if any of the thousands Great North Runners will know that after about two miles they pass within half a mile of his grave every year. Like many other peds he dabbled in training, preparing William Bell of Felling to defeat Edward Mills for £50 a side at the Victoria Grounds in December 1861.[25] Mills had beaten Rowan himself over ten miles at the Victoria in June. Evidence that not only sprint handicaps started by mutual consent is shown in 1855 when Rowan took on Saville at the famous Hyde Park grounds in Sheffield.[26] He was the Gazza of his day and Rowan emerged the spirit of the north, a hero athlete, embracing excellence, human frailty, romance and glory.

Jack White

John `Jack` White, the Gateshead Clipper was a different type of man but like Rowan was a very versatile athlete.[27] Watman describes White as probably the least known of history`s great distance runners.[28] He soon became noticeable in his running attire of white vest and blue spotted drawers and as a non drinker through his Methodist Temperance background he was the complete opposite to Rowan. Following a family disagreement over his running, possibly linked to the sport`s relationship with alcohol, he eventually settled in London with his wife and six children but was never to lose his accent. He was born in Gateshead on 1 March 1837, the third oldest of five born to Ellen and his father William a millwright. In modern terms a millwright is a craftsman or tradesman engaged with the erection of machinery. In the early part of the industrial revolution their skills were used in building powered textile mills, initially working with wood followed by metals. The 1851 census indicates he was still living at home in Easton Street employed as apprentice millwright. Following his retirement from running in 1870 he carried on his engineering skills on a part time basis, and these certainly were put to use in running related projects. At various times in his running career he held the British four, five, six and ten mile records. He first appeared running professionally in Newcastle in 1857, losing his first race over 880 yards to Rowan. He soon became known to George Martin, the wizard of pedestrianism and famous Manchester trainer/promoter, and consequently moved to Salford for a time. Martin, in his own pedestrian career, had taken part in various matches in neighbouring Wearside. White, like others, soon became at great attraction at the Hackney Wick venue in London, created by James Baum proprietor of the White Lion in Wick Lane. By the end of 1860, Jack was British champion over four, six and ten miles, receiving the accolade of the best pedestrian ever known in England. In 1861, Martin took White to America for a lucrative trip where he remained unbeaten, including wins over Deerfoot. The intense local rivalry between Rowan and White continued and in the race of the year in 1861, 5,000 people turned up at Newcastle`s Victoria Grounds to see Rowan defeat White over 880 yards for the title ‘Champion of the North’. White was possibly more successful over the longer distances and his good form continued. Remarkably en route to a victory over ten miles in 1863 in Deerfoot`s last race in Britain, a race which could be described as the who`s who of running at the time, White after starting at his customary suicidal pace broke the British three, four, five and six mile records, in his best ever race.[29] He was known to ignore Martin`s advice and adopt his own tactics. This was not his only tactic and he often destroyed the field by his change of pace and mid race surges.[30] He was then declared the best pedestrian the world had ever seen. His six mile time of 29 minutes 50 seconds was to stand as a world`s best until it was beaten by Paavo Nurmi in 1921. As a British record the time survived until 1936 when another Geordie Alex Burns from Elswick Harriers shaved five seconds from White`s time.[31] William Lang of Stockton was with White at the six mile point but dropped out shortly afterwards.[32] Controversially Hardgraft gives evidence of certain tricks performed at Hackney Wick to make records easier to achieve by running shorter distances by shortening the bend on one side. White had befriended Walter George and, in 1938, George, in his eighty-first year, spilled the beans in a letter to the News of the World, suggesting White`s phenomenal records in the 1863 race might not have been all they seemed.[33]

White continued to race at a high level and lost his last race over five miles in 1870. White had also made a notable appearance at the famous Shropshire Much Wenlock Games in 1862 where a controversial incident reinforced the reputation of professionals for dubious practice, at the same time indicating the rising need for nationally accepted athletics rules.[34] Rowan and White dominated their sport during its heyday of the early 1860s and possibly the nine belts and eleven British best records set mostly in London compared with Rowan`s four belts and two records gave White the edge, but in head to heads Rowan was the better. Certainly in the historiography of pedestrianism White`s name regularly appears. White had a much more stable personality than Rowan and, in his retirement, as was the norm with retired performers, used his knowledge and made part of his living as a trainer and coach. In 1869, he was invited to train officer cadets at the Royal Military Academy and this certainly indicates he was considered reliable and temperate. Running was his life and his service to the sport as well as a trainer included handicapping, starter, timekeeper, referee, manager, groundsman and attendant to long distance walkers, when this became the craze. He was unsurpassed in his knowledge of athletics and Roe described him `as the most celebrated starter in London`.[35]

On his competitive retirement he lived in Fulham and as a member of the ground staff at the nearby Star and Lillie Bridge Grounds he trained both pedestrians and the amateur London Athletic Club (LAC) in the 70s and 80s. Again Roe states there could be no more a deserving manager of a pedestrian running ground than the celebrated Gateshead Clipper.[36] In 1878 he directed the construction of the track at the Agricultural Hall, London for the six day championship of England and in 1886 not only did he fire the gun in the mile of the century` between Walter George and Bill Cummings, he was also the timekeeper.[37] Hadgraft reports scenes of panic involving a huge crowd waiting to get in when White tested his starting pistol causing some outside thinking they had missed the start. During 1889, one of his LAC successes as a coach was Sid Thomas who won five AAAs titles and broke two world records between 1887-1895. Thomas like others was to be banned by the AAAs for accepting illegal expenses. In 1893, White had secured employment as a club servant to coach Cambridge University Athletic Club, quite an honour for a pedestrian and the classic case of professionals being employed as trainers, yet condemned for training in their own running career. In 1905, White was employed as assistant coach at Chelsea FC. His coaching career ended at Cambridge and he died in Fulham in 1910 following a period of ill health many years after The Era reported how he came up `to the metropolis from the banks of the coaly Tyne, and completely took the natives by surprise with his capital style of running`.[38] Both Rowan and White contributed a great deal to the sport locally and, as a result, handicaps became bigger and more valuable. White`s appearances at home however were minimal. Roe, listing his performances, highlights only four at the Victoria Grounds, but the regional press report on others. Roe`s record, nevertheless, emphasizes White`s achievements. His performances include 31 wins, 21 seconds and 1 third in major competitions with 6 forfeits, 3 in his favour.[39] The early greats Wilson, Rowan and White all fit Stonehenge`s pedestrian somatotypes; all three were light, wiry and springy and in many ways this related to their working-class Tyneside upbringing.[40]

Another runner who achieved national status was Gateshead`s Stephen Ridley, the younger brother of song writer George Ridley. In 1870, Stephen won the mile handicap at Powderhall from scratch. Neither Rowan nor White ran their best times on home ground but Ridley took his national mile title at the Gateshead Borough Gardens in 1881 and retained it the following year. He stayed in the sport as a starter and referee. His brother George Ridley, famous for the song Blaydon Races, ensured the feats of Tyneside sportsmen including pedestrians went down in history, hailing national champions and acknowledging local ones. The achievements of White and Rowan and other runners coincided nicely with the explosion of the concert hall business in Newcastle. In song, Ridley celebrated Joseph Hogg`s local victory over Joseph Foster at the Newcastle Victoria Running Grounds.[41] The lyrics of the first verse of Hogg and Foster`s Race to the tune of Kiss me Quick go:

`T`uther Seturday neet aw saw a grand foot race alang at the Victoria grund,

Between Tout Foster an` Joe Hogg an` the stake was fifty pund;

Thor was lots o` cheps getting` on their bets, thor was little odds on Tout,

The cabs wor standin` at the gate, aw saw Joe Hogg luik oot.`[42]

Similarly in another song he sings of Bob Bullerwell`s win over Summers at the Victoria Grounds in Newcastle.[43]

Aw`m gawn te tell ye aboot a race

That cum off som time back,

Tween Summers an` Bob Bullerwell

This Summers was all the crack,

The race was at the Victoria Grund,

An` Summers was gaun te flee,

Says Bob `Aw cum fra` Blaydon,

An` ye`ll not get ower me.’

Not only on Tyneside were the feats of the peds recorded on song as, for example, in English Sporting Balads `a great foot race` is sung between Richard Hornby, alias `Long Dick`, and George Eastham, alias the `Flying Clogger, that took place near Preston.[44] Jerry Jim from the same area is another mentioned in a number of foot race songs.

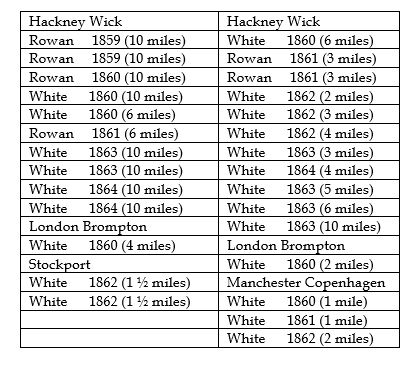

With Rowan and White setting their best performances in London, the question must be asked why their native Tyneside with improved running grounds, failed to witness records or Champion Belt challenges. Perhaps promoters failed to offer sufficient money to attract lucrative matches, although a `Great Five Mile Handicap Race` took place in September 1861 at the Old Victoria attracting the best of the day including Bell of Felling, trained by Rowan.[45] Felling borders Gateshead and Bell often returned from London successful and in 1861 recorded a famous victory over Londoner Eric Mills over five miles at the Victoria Grounds with 2,000 present. Table 1 shows how London in particular was the favoured venue for major races and record performances.[46]

Throughout the country, pedestrian events for women (pedestriennes) were infrequent and publicity was rare and every aspect of sport was male dominated. However, one woman in particular was well known for her efforts along with her sons, Irish born Mary McMullen, and her performances on Tyneside are reported in the 1820s.[47] Her son Peter is recorded walking 100 miles in 24 hours on the Town Moor race course, at the same time his sixty-four-year-old mother covered 92 miles in the same time. She finished exhausted and only about £20 is recorded as having been collected for the `poor woman`. Two months later, close by Bishopwearmouth, she was stopped by the police only two hours into a 96 mile attempt in 24 hours on the roads, allegedly for begging. Mary and her family were known to travel all over the country taking part in long distance walks.

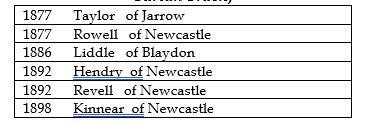

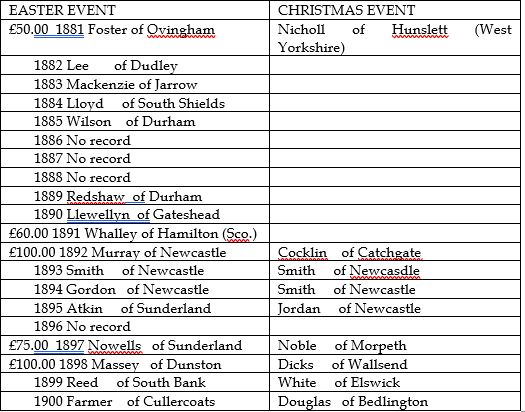

Table 1. Champion Cups and Belts. British Records (Roe, Front Runners).

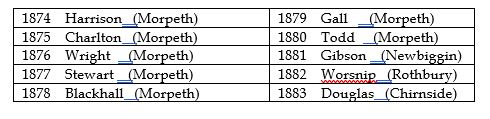

In the neighbouring counties, pedestrian running was also popular. According to Murfin, athletics in Cumbria was a professional sport which merged imperceptibly into pedestrianism and cycling or penny farthing races organized by publicans were often against pedestrians.[48] South of the Tyne, as early as 1723, races were held on South Shields sands until they were prohibited by an Act of Parliament in 1740, as they were seen as a cover for Jacobite gatherings. They were revived in 1825 but a fatal riot in 1855 led to them being outlawed once again. With foot racing being one of the most popular pastimes amongst miners, Sunderland and Durham coalfields attracted enthusiastic support. Further south on Teesside, Stockton born William Lang was one of the tallest pedestrians of his day, when the sport was at its peak. As well as participating in sprint races, pitmen in East Northumberland often made the long journey by foot to support their heroes in Newcastle and, on their own patch, running grounds at Ashington, Bebside, Bedlington, and Blyth were the most popular. Competitive by nature, pitmen were regularly challenging others to tests of speed and endurance; heroes tended to be local, but in the twentieth century, Northumberland sprinters regularly made their mark at Powderhall. Table 2 showing the first ten winners of the main sprint at the Morpeth Olympic Games indicates it was 1883 before a winner came from further afield. Miners such as Will Summers of Shiremoor became recognized throughout the coalfield for their athletic prowess. The importance of pedestrianism is perhaps best illustrated at the funeral of James Reay, also of Shiremoor, a leading local runner, who was killed at Backworth pit in 1895. The funeral attracted over 5,000 mourners, a vivid illustration of the importance of runners in miner`s lives.[49]

Table 2. Main Sprint winners at the Morpeth Olympic Games. (Moffatt, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track)

Race Venues

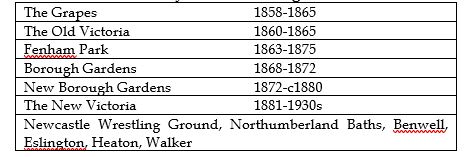

With no convenient private venues, from 1828 the favoured places for pedestrian run offs were on turnpike roads especially at Bulman village (now Gosforth), Three Mile Bridge, Wallsend, the West turnpike and Birtley. The race course on Newcastle Town Moor prior to this had been the favoured location. Handicap racing was then added to the Great Northern Wrestling Games held in their own wrestling grounds.[50] Despite increasing popularity from 1839, matches on the turnpike roads led to problems, so the era of racing in commercially viable enclosed running grounds (Table 3) with the blessing of the police remodelled the sport. Apart from the London running grounds there is little documentation of these facilities in northern cities.[51] The increased number of races taking place and the resultant police interference so led to the era of running grounds. In 1858 the first original running track the Grapes was opened on Westgate Road near the work house, but with a length of two hundred yards, the more popular long distance races soon moved in 1860 to superior accommodation at the 444 yard long Old Victoria Grounds, west of the infirmary, close to the Wrestling Grounds and by 1865 the Grapes had closed.[52] At this point, vacant land opposite the Northumberland Baths also saw many matches take place. The Baths were on the same site as the recent controversially closed City Pool. One popular feature at the Victoria ground was a purpose built stand accommodating the Fancy and crowds of up to 6,000 for featured races were common. When the land was bought by the North Eastern Railway Company for expansion purposes the licensing firms of Sterling and Emmerson laid out the Fenham Park Grounds on Ponteland Road, at Nuns Moor on the western fringes of the Town Moor, close to the golf course of today and this became the premier running venue in the area. The Fenham Grounds bill also featured dog racing and rabbit coursing as well as staging novelty races. The national sporting press in 1864 singled out Fenham as a place for excellent matches and at almost 600 yards long it was ideal for all distances. Although 2½ miles from the city centre it was well patronized due to the excursion trains put on by railway companies who advertised in the local press.

This was at a time when there was a rise in prosperity for working people on Tyneside and many of Newcastle`s taverns accommodated visiting runners, displayed belts and fixed matches. Popular Newcastle hostelries famous for organizing matches include the Adelaide Hotel, the Fighting Cocks and the Old Plough Inn in the Bigg Market. The Bigg market seemed to be the hub of the sport with Lowthers, another known betting shop and the Scotch Arms Inn two of many to attract supporters. Over the river James Rowan is most likely to have spent many an hour in the Dun Cow Inn in Dunston; the pub is still open and popular amongst sportsmen. The Adelaide in Benwell, now pulled down, was a particularly famous sporting house whose licensee William Blakey was a staunch supporter of the Newcastle sporting scene; Renforth`s skiff the ‘Adelaide’ was named after the premises. In 1870, Robert Sterling named above was fined £20 by Newcastle Police Court for running a betting house at the Old Plough Inn.[53] In 1868 competition grew in the form of the Borough Gardens Track across the river in Gateshead, also with local licensing trade backing. The term Borough Gardens was also in favour in Preston and Salford. With a track of 510 yards including a 300 yard straight the ground quickly became famous, but, once again, the same fate as at the Old Victoria Grounds struck, the railway company who owned the land required it for re-development and the track closed in 1872. Fortunately for the promoters, a new site near the old Friars Goose colliery opened as the New Gateshead Borough Gardens.

By the end of the 1870s, foot handicaps at the Borough Gardens were in decline and, across the river, the New Victoria Ground, situated where the Metro Arena is now, opened in 1881 and soon became the best and most popular running ground in Newcastle until its closure in the 1930s.[54] The new Victoria regularly attracted attendances of over 6,000 and the Newcastle Wrestling and Athletic Games at Easter were now held at the `Vic`. The `Victoria Pedestrian Company` offered £100 prize money for all holiday events and such prizes were a fortune to a man earning 25 shillings a week. Certainly, the holiday weekends were the best time to stage better class events. Until Heaton and Walker opened near the end of the century, the Newcastle running grounds were situated in the west end of the city. Despite the provision of a number of running grounds, no national best performances were set at Tyneside venues.[55] The only exception was by W.Johnson over 130 yards with a strong favourable wind at the Fenham Grounds in 1867, timed by W. Oldham.[56] Johnson beat Brown of Manchester in 12 and 1/8 seconds on 9 February.

Table 3. Tyneside Running Grounds

Sprinting

Newcastle and Gateshead however could still not boast of a short distance champion and the names of very few Tyneside sprinters roll of the tongue, yet it was the Tyneside professional sprinters who carried the pedestrian legacy in the twentieth century at Powderhall, the Borders and the Lakeland Professional Games (table 4).[57] During the days of Rowan and White sprint handicaps had been extremely popular on Tyneside yet local sprinters disliked travelling to Sheffield, the home of handicap racing. According to Moffatt, it was not only the distance to travel that put local sprinters off but Sheffield`s poor reputation where more guile than speed was needed (Table 5).[58]

Table 4. NE Powderhall Sprint Winners up to 1970 (the last year held at Powderhall), since then Smart of Whitley Bay (1988) won at Meadowbank and Telford of Newcastle (2002) and Charlton of North Shields (2004) at Musselburgh (www.newyearsprint/ sportingworld.co.uk)

Table 5. NE Sheffield Handicap. (Moffatt, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track)

Tyneside is similarly criticized by Carruthers, who reports on the dubious arrangements behind the scenes and the rough tactics on the track in Newcastle.[59] Two examples are Blagburn taking Forrester to court in 1862 following Forrester being awarded a win in a novice handicap, when in fact he was an experienced runner and also in the same year the Newcastle Journal reported `when the men were going round for the last lap a great many of the roughs broke over the paling`.[60] Meetings held on Tyneside and the East Northumberland coal mining towns and villages unsuccessfully attempted to follow the rules of the `Association of Running Grounds of Sheffield` in an attempt to get uniformity, following regular criticism over incorrect measured distances, numerous false starts and non-triers. One instance recorded thirty three false starts. Most of the East Northumberland sprint meetings were held under Morpeth Handicap Rules, whereas on Tyneside and in the South Northumberland Flower Shows incorporating sprints such as at Seaton Burn and Cramlington the Victoria Rules were strictly enforced. Clearly, no agreement could have been made locally.

Table 6. Winners of Victoria Grounds, Newcastle sprint handicaps up to 1900 ( Moffatt, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track)

Table 6 clearly indicates that very few winners at the Victoria Grounds travelled from a distance. The lack of successful Tyneside sprinters is noted in John Bale`s research. Bale`s studies indicate the national regions associated with certain athletic events. North East England is strongly associated with distance running and is ranked second nationally; this can be partly attributed to the success in recent years of Foster, Cram etc. and the legacy of the Tyneside pedestrians in the nineteenth century. On the other hand, evidence suggests sprinting in the North East is ranked the weakest of all the regions in England and Wales.[61] £100 handicaps are recorded to 1926 (including war years), £50 in 1927/28 and then only smaller £25/£35 events held at irregular intervals till the close of the running grounds. Following some small races in 1934, the famous Victoria Grounds closed. Names like the ‘Vic’, Eslington, Benwell and the rest of Tyneside running grounds are now just memories.

-

The Adelaide Hotel, Elm Street, Benwell

A famous Newcastle upon Tyne nineteenth century sporting house.

Conclusion

Professional running was a good target for respectable Victorian opinion; it could hardly fit in with the ideologies of sportsmanship and fair play. These public concerns were to bring about its demise. Jack White`s death in 1910 as a local hero was probably the last living link between respectable athletics and a shadier discredited sport which had attracted large crowds on Tyneside years before. Pedestrianism however did leave a durable legacy on Tyneside. Both Rowan and White raised the profile of athletics in the area. Rowan`s training route saw the start of what was Britain`s oldest road race. Races such as the Morpeth encouraged the birth of mass participation events. The success of the Great North Run in no small measure has been due to the role of sport in North East cultural tradition. Another legacy was the success of area`s distance runners spanning the Victorian peds to Alder, Foster, McLeod and Cram in recent times.

The dropping of the mechanics clause from AAA`s membership, fought for by the Northern Counties AAA, saw the enthusiasm for distance running by ordinary people move to the newly formed local amateur harrier clubs from 1887. Clubs like Elswick Harriers (formed in 1889) and Heaton Harriers (1890) have continually thrived since. Tyneside, however, in a change of sprinting fortune, began to produce professional sprinters of note well into the twentieth century. The closure of many pits in the second half of the century with its social consequences coincided with the demise of sprinting talent. Sprint meetings such as Mickley and Thropton, west of Newcastle on the Tyne, the Ashington, Bebside and Blyth sprints, flower show handicaps and the professional Morpeth Olympic Games were all lost for good. None of the commercial running grounds survived, but Gateshead International Stadium, first opening as an athletics track in 1955, now stands close to where the New Borough Gardens attracted the crowds in the 1880s and the success of Brendan Foster, as a local athlete, mirrors that of Rowan and White in popularizing their sport and encouraging participation in it.

References

[1] William Lawson, Lawson`s Tyneside Celebrities: sketches of the lives and labours of famous men of the north, Newcastle: self published, 1873, 311.

[2] Don Watson, ‘Champion Peds: Road Running on Victorian Tyneside’, North East Labour History, 1994.

[3] Saltwell Harriers Road Race Centenary Programme, 2011.

[4] Simon Turnbull, ‘Foster father for a race against time’, The Independent, September 12, 2010.

[5] Fred C. Moffatt, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track, self published, 1979, 20.

[6] Thirty Years of Walking, Souvenir Booklet of the Records and Achievements of Tom Payne, South Shields Harriers; Tom Payne the World Famous Musician-Athlete.

[7] Peter Radford and A J, Ward-Smith, ‘British running performances in the eighteenth century’, Journal of Sports Science, January 2003.

[8] Peter Radford, ‘The time a land forgot’, The Observer, May 2, 2004.

[9] Adrian Harvey, `Wilson, George, (b.1764 d. in or after 1822)`, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Warren Roe, Front Runners; Moffat, From Turnpike Road to Track Track.

[10] Peter Radford, The Celebrated Captain Barclay (London: Headline Book, 2001), 233.

[11] Lawson, Lawson`s Tyneside Celebrities, 311.

[12] Radford, The Celebrated Captain Barclay.

[13] George Wilson, Memoirs of the life and exploits of G. Wilson the celebrated pedestrian, (London: Dean and Munday, 1815).

[14] Tom McNab, Peter Lovesey and Huxtable, An Athletics Compendium, an annotated guide to the UK literature of track and field, (Wetherby: The British Library, 2001), 12.

[15] Richard Holt, ‘Sport on Tyneside’, in R., Colls, and B. Lancaster, editors, Newcastle upon Tyne, a Modern History, (Chichester: Phillimore, 2001), 195.

[16] Harvey, Oxford Dictionary.

[17] Newcastle Courant, May 15, 1824.

[18] The Tyne songster, 1840, a choice of songs in the Newcastle dialect, On Russell the Pedestrian.

[19] Warren Roe, Front Runners, The First Athletic Track Champions, 45; D. Watson, ‘Popular Athletics on Victorian Tyneside’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 11, no. 3 (Dec.1994); Moffatt, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track.

[20] Tall Tree Pictures, Arthur McKenzie narrative. NB. the project to make a film about Rowan was aborted.

[21] Sports Illustrated, April 1976, `Howay Big Bren, Ye`r Doing Us Prood`.

[22] Watson, ‘Popular Athletics on Victorian Tyneside’, 486.

[23] Era, April 29, 1864.

[24] Newcastle Journal, December 12, 1864.

[25] Newcastle Journal, December 2, 1861.

[26] Newcastle Courant, November 23, 1855.

[27] Roe, Front Runners, 33; Watson, ‘Popular Athletics on Victorian Tyneside’; Moffat, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track.

[28] Mel Watman, History of British Athletics, (London: Robert Hale, 1968), 108.

[29] Bob Phillips, The Iron in His Soul, (Manchester: The Parrs Wood Press, 2002), 40.

[30] Rob Hadgraft, Deerfoot Athletics` Noble Savage, (Southend-on-Sea: Desert Island Books, 2008), 31.

[31] Nick Murray, The Boys in Red, Elswick Harriers 1889-1989, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Elswick Harriers, 1989), 36.

[32] Roe, Front Runners, 124.

[33] Hadgraft, Deerfoot, 181.

[34] Catharine Beale, Born Out of Wenlock, (Derby: Derby Books, 2011), 53.

[35] Warren Roe, Jack White `The Gateshead Clipper` 1837-1910, A Life of Athletics, (Hornchurch: self published, 2007), 43.

[36] Ibid, 38.

[37] Paul S. Marshall, King of the Peds, (Milton Keynes: Authorhouse, 2008), 151; Peter Lovesey, The Kings of Distance, (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1968), 64; Rob Hadgraft, Beer and Brine, The Making of Walter George Athletics` First Superstar, (Southend-on-Sea: Desert Island Books, 2006), 119, 182.

[38] Era, September 23, 1860.

[39] Roe, Jack White, 69.

[40] Stonehenge, British Rural Sports, 1886, 616.

[41] David Harker, Gannin` to Blaydon Races! The life and times of George Ridley, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Tyne Bridge Publishing, 2012), 53, 60, 102, 103; Gannin` to Blaydon Races! CD tracks 7, the Northumbria Anthology.

[42] Gannin` to Blaydon Races! Track 7, verse 1.

[43] Gannin` to Blaydon Races! Track 10, verse 1.

[44] English Sporting Ballads, track `the great foot race`, Celtic Music, 1998.

[45] Newcastle and Tyne Mercury, September 1881.

[46] Roe, Front Runners.

[47] Peter Radford, ‘Women`s Foot-Races in the 18 and 19 Centuries: A Popular and widespread Practice’, Canadian Journal of the History of Sport, 1994, 55; Newcastle Journal, September, November 1828; Lawson, Tyneside Celebrities, 313.

[48] Lyn Murfin, Popular Leisure in the Lake Counties, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 109,122.

[49] Alan Metcalfe, Leisure and recreation in a Victorian Mining Community, (London: Routledge, 2006), 109.

[50] Moffat, From Turnpike Road to Tartan Track.

[51] Samantha-Jayne Oldfield and Dave Day, Running Pedestrianism in Victorian Manchester, Social History Society, Annual Conference, April 2012.

[52] Alan Metcalfe, ‘Sport and Community: a case study of the mining villages of East Northumberland, 1800-1914’, 13, in Sport and Identity in the North of England, edited by J. Hill and J. Williams, (Keele: Keele University Press, 1996); Lawson, Tyneside Celebrities, 314.

[53] Newcastle Guardian and Tyne Mercury, June 25, 1870.

[54] Lyn Pearson, Played in Tyne and Wear, (Swindon: English Heritage, 2010).

[55] Rowan and White`s records were set in London and Manchester.

[56] Stonehenge, British Rural Sports, 1886, 631.

[57] John Franklin, Gold at New Year, (Hawick: Tweeddale Press, 1972), 34.

[58] Moffat, From Turnpike Road, 26.

[59] Tom Carruthers, Running for Money, Kidworth Beauchamp: Matador, 2012), 108.

[60] Newcastle Journal, October 27,1862; February 11, 1862.

[61] John Bale, Sport and Place, (London: C. Hurst and Co., 1982), 116.

I think my great grandfather may have taken part in one of these races. Is there ant way of finding out?