2017 is the two hundredth anniversary of the longest foot race ever to take place in England. In the late eighteenth century long-distance, multi-day events had become popular with self-described ‘gentlemen amateurs’, who walked for large money wagers. The fashion culminated in a famous match where Captain Barclay walked one mile every hour for 1,000 successive hours (41 days and 20 hours) for 1,000 guineas at Newmarket in 1809.

- The famous Captain in his walking attire (from Walther Thom, Pedestrianism (Aberdeen, 1813)

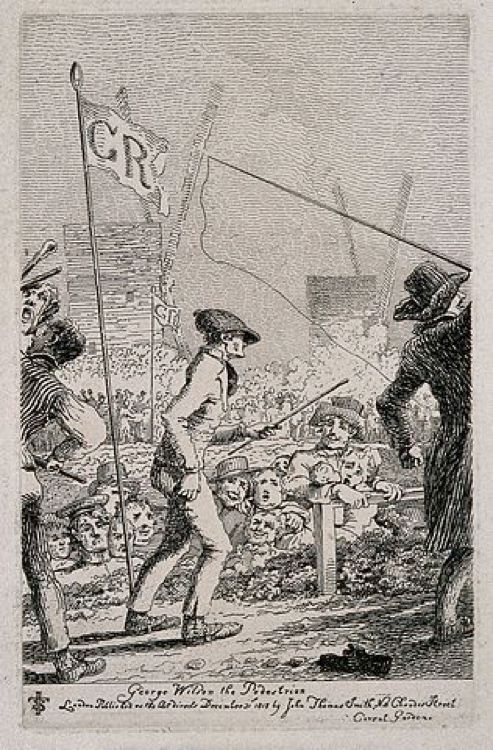

Working class pedestrians (a ‘pedestrian’ was any athlete, a runner or a race walker) replaced the gentry as the main practitioners and began to attract mass audiences. The pioneer was George Wilson, a weedy 50-year old itinerant pedlar from Newcastle-on-Tyne. His attempt, in September 1815, to walk 1,000 miles at 50 miles a day at the Hare and Billet pub on Blackheath provoked scenes of uncontrolled rowdiness. When he had to be protected from over-enthusiastic supporters by minders with staves and horse whips, the authorities feared civil disorder and stopped his walk after 750 miles.

- George Wilson and some excited supporters at Blackheath September 1815

But ‘pedestrian mania’ was unstoppable. The pedestrians learnt to cope with the vast distances, entrepreneurs learnt to organise and control multi-day events and the authorities prudently refrained from interfering. By the end of 1816 there had been another dozen 1,000-milers. Pedestrians walked for money – some were subsidised by publicans, some walked merely to solicit donations, the more skilled pedestrians were backed by individuals or syndicates and walked for wagers.

They were solo events – the pedestrian against time or distance. But in 1817 an unusual contest was agreed. Two pedestrians would walk 42 days, the winner to be the one who reached 2,000 miles first, or, failing that, the greater distance. The wagers were 100 guineas a side but it was said that eventually £100,000 (several millions in today’s values) was bet on the contest.

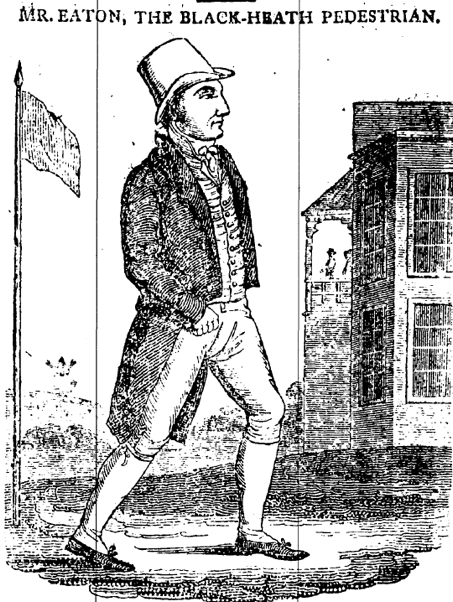

On one side was Josiah Eaton. Born in Woodford in Northamptonshire, he was a baker by trade who had taken up pedestrianism at the age of 45. He had walked 1,100 miles in 1,100 hours (45 days) on Wilson’s course at Blackheath in 1815 and in 1816 confirmed his status as the country’s leading endurance walker by an unprecedented feat of stamina – he walked half a mile in each of 2,000 consecutive half hours (42 days) at Brixton. Against him was 34 year old John Baker from Kent, an experienced pedestrian who had walked 1,000 miles in 20 days at the Cossack public House in Rochester in 1815. Eaton was older but had the better pedigree and was the favourite in the betting.

- Josiah Eaton walking 1,100 miles at Blackheath (The Star, 17 November 1815)

The match conditions were that they could walk at will between four in the morning and eleven at night. The venue was Wormwood Scrubs, then an open common already known as a venue for prize fights and occasional horseracing (the famous prison was not built until sixty years later). Along its northern edge ran the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal, opened in 1801, on the northern bank of which was the Mitre Tavern, a stop for pleasure boats from Paddington and barges on their way north. By road it was just over two miles from Hyde Park Corner. Two 220 yard tracks were marked out parallel to each other and about 20 yards apart on the south bank of the canal and the pedestrians walked out and back, four laps to the mile. Two marquees were erected at the starting post and here the pedestrians and their handlers lived for the duration of the match. Watchers were appointed from each side and daily progress reports appeared in the Morning Post.

- Wormwood Scrubs and the Mitre Tavern in the early nineteenth century

After a two-hour prologue on Wednesday 7 May (they each walked 10 miles) hostilities proper began at four o’clock the following morning. Both adopted a steady but relentless pace and when they retired to their tents at the end of Thursday Baker was three laps ahead, 65 miles to Eaton’s 64¼. On Friday he increased his lead to 6¾ miles. On Sunday crowds came out from the city to watch the walkers pass the 200-mile mark with Baker retaining his lead.

After seven days they had reached 300 miles (Baker 7 miles ahead) and after two weeks 600 miles (Baker still just ahead). At the mid-point, Wednesday 28 May at four in the afternoon, Baker was leading by 14½ miles, 997 to 982½. By now the pattern of the race was well established, Baker started later in the morning, walked faster and finished earlier in the evening. Eaton continued, often walking an hour longer, but never quite overhauled Baker. A bet of 100 guineas on Baker was reported but many ‘knowing ones’, relying on Eaton’s proven stamina, continued to bet on him. The gap between them remained tantalisingly narrow – Baker’s tactics were to keep just ahead, conserving his strength and avoiding breakdown, or deliberately keeping the contest close for betting purposes, or probably all these motives.

With two weeks to go interest intensified. The Duke of York and other ‘persons of distinction’ visited in ‘splendid equipages’ or on horseback. Some gave the pedestrians money (they got £10 from the Duke of Gloucester). Booths and stalls had invaded the common and the proletariat flocked ‘in huge numbers.’ In one day 20 butts of beer (2,200 gallons) were drawn at the Mitre. Saturday 14 June (day 38) saw the largest crowds, the canalside was thronged and the pleasure boats were crowded. The St. James’s Chronicle said ‘the metropolis appeared to have emptied itself into Wormwood Scrubbs’ and guessed that 50,000 were present. On Sunday evening Baker’s lead was 9 miles and with only two and a half days left only injury or misfortune could prevent his victory. On Monday he was sick, having taken ‘an extra pipe of tobacco,’ but he recovered the ground he lost and by Wednesday morning, the last day, he had only 18 miles to go. He started at six o’clock and by seven minutes past one he had completed 2,000 miles, 9¾ miles ahead of Eaton, who carried on for the satisfaction of reaching his 2,000 miles just ten minutes before the 42 days expired at four in the afternoon.

Pedestrians continued to do huge endurance feats against the clock for a couple of years, but by the end of the decade the public had lost interest. Contested races over preposterous distances did not become popular again until the craze for six-day races in the 1870s, but (perhaps unsurprisingly) the 2,000-mile race of 1817 was to remain a unique memorial to two unheralded athletes of the early nineteenth century.

Article © Derek Martin

I like your articles about Pedestrianism. I lived near where Captain Kelly lived he was a friend of the famous waker Captain Barclay and the fought in the Napolenic wars.

My question is do you know anything about a famous Pedestrian who lived near Mannheim in Germany in the 19th century. He was also an

acquaintance of Karl Benz. Any information would be so appreciated.

I am also an author in my spare time. My first book was At The Greatest Speed and my second will be about Early Cars (working title)