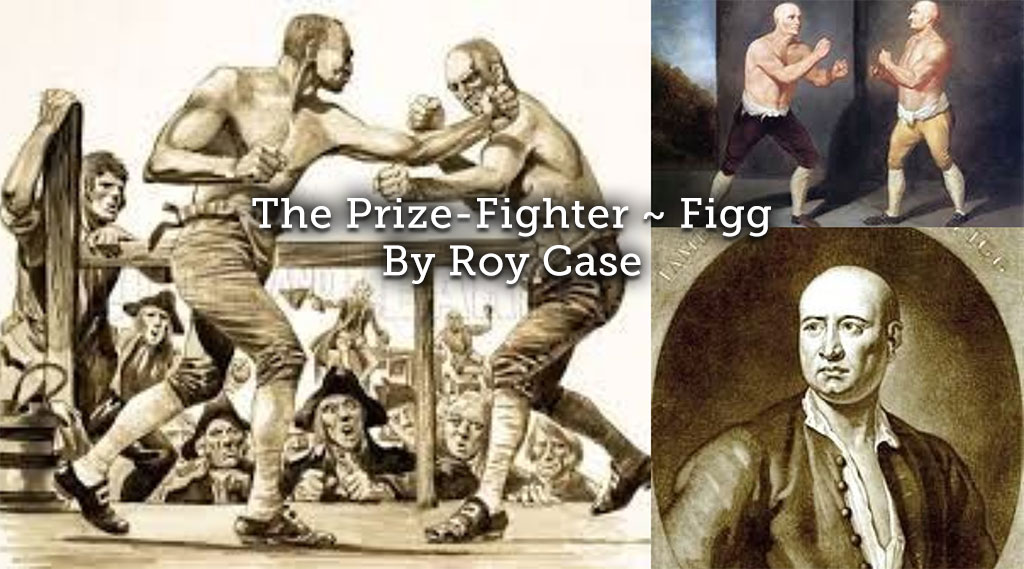

During the early part of the 18 century bare-knuckle boxing came into its own. It differed from street-fighting in that it had an accepted set of basic rules, which involved two individuals fighting each other without any form of padding to the hands.

Before the basic rules of pugilism were modified, bare-knuckle combat was only one speciality numbered amongst several other disciplines, including combat using foils, cudgels and quarter staffs, grappling techniques, throws, arm locks, chokes and kicking. With the passing of time such techniques were progressively prohibited, as those associated with the modern sport of boxing were developed.

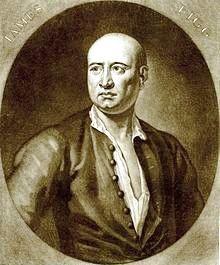

The first great pugilistic to figure in British history was James Figg, who was generally acclaimed as being more adept with the sabre and staff.

- James Figg [1684-1734]

In 1684 James Figg was born into a poor, illiterate farming family in Thame in Oxfordshire. The youngest of seven children, he was a rough, tough youngster, who learned the prize-fighting profession journeying around local fairs issuing challenges to do battle against booth fighters.

Fully grown he stood around six feet tall and weighed in at just over 13 stones [185 lbs]. Fit and fast, he based himself at the Greyhound Inn in Cornmarket, in his home-town of Thame, where he accepted challenges to fight all-comers, and in addition gave lessons in self-defence to those in need. James supplemented his income further by travelling to fairs throughout the Midlands accepting challenges from noon until sundown. He was eventually discovered by the noted English military leader, and sporting patron, the 3rd Earl of Peterborough, Charles Mordaunt KG, PC [1658-1735], while fighting and staging exhibitions of his skills with short-sword, staff and club, at fairs in his native Oxfordshire.

At the time the defensive arts flourished through aristocratic patronage, with wagers on the outcome of bare-knuckle contests considered an important appendage to the sport. And since the Earl of Peterborough, enjoyed both sport and gambling in equal measure, he made Figg a generous offer to back him. Subsequently, launching the ‘bull-necked brawler’ in London, where Figg fought at Southwark Fair in his own booth, taking on multiple opponents and proving himself more than a match for any man in single combat.

Most of his early professional prize-fights were fought in and around London, where they were commonly publised in the newspapers. Although precise records were not kept at the time, it is believed Figg fought a total of 270 fights and lost only once. Openly acknowledged as the first bare-knuckle champion of England, a title Figg claimed in 1719 and held until his retirement eleven years later.

In that same year James Figg established his own prize-fighting academy, just north of Oxford Street, where he tutored a core of powerful prize-fighters. He also schooled boxing, fencing, and the use of the quarterstaff, to a number of the sons of nobility, who sought training in the ‘art’ of pugilism and self-defence.

According to a former student, schooling under the guidance of Figg was a brutal business, with no exclusive empathy reserved for young gentlemen. He described Figg as a man possessed with a ‘rugged temper, who would spare no man, high or low, who took up a stick against him’. Adding, ‘I purchased my knowledge with many a broken head, and bruises in every part of me.’

Sometime around 1723, Figg sub-let his amphitheatre to another boxing master, and resumed his prize-fighting profession, competing about once a month, alongside women and animals, at the ‘Boarded House’ located behind Oxford Street, in Marylebone Fields.

Prize-fighting was a boisterous and brutal affair, consisting of three rounds, during which slapping, kicking, biting and gouging were commonplace. The first round was fought with short-swords, the second with fists, and the third with the quarter-staff, short-staff, or sometimes a club. The quarterstaff was composed of a shaft of hardwood, six to nine feet in length, with a metal tip, or spike, attached to each end. As a weapon it was deemed to be more advantageous than the long-sword, for although visually less threatening, it could be equally as deadly. Bravery and considerable skill were fundamental requirements of a successful prize-fighter, with as much as £ 3,000 wagered on the outcome of a single bout.

Figg’s capability as a fighter was unsurpassed throughout his reign as the champion of England, but as has almost always been the case in the history of sport, true greatness requires a rival to emerge in order for it to be confirmed. Figg’s greatest rival came in the form of a pipe-maker, by the name of Ned Sutton, from Gravesend.

In the pair’s first encounter in 1725, Sutton defeated Figg and claimed the English title. But the resolute Figg demanded a re-match, and the most famous clash between the rivals took place in June 1727. This contest was held at the famed Adam and Eve venue, on the road heading north from London. Renowned as the most celebrated arena for prize-fighting at the time, it was also fêted for all manner of entertainment. On the chosen day the amphitheatre was filled to capacity, with standing room only for the eager spectators to observe the great challenge match, and place their bets on the ultimate outcome.

The ensuing battle was a contest of combat skill, with the first round of the contest fought with swords. Sutton launched into an opening attack, driving Figg back, and forcing him to slice himself on the arm with his own blade. However, the wound was not considered sufficiently severe to end the bout, and the pair continued to parry back and forth, until Figg drew blood with a wound inflicted to Sutton’s shoulder. Each round continued indefinitely, until one of the fighters was knocked down or thrown, and should the downed fighter be able to manage to make it back to the scratch line, then the next round would begin.

At the end of the first round, both the crowd and the fighters, took a short break, during which they refreshed themselves with ale. Following which the second round, the fist fight began, in which grappling, clinching and throwing were equally as important as punching, and kicking a downed opponent was also considered a valid technique, as was gouging at the eyes. It was in this area of combat that Sutton was closest to matching Figg’s ability. The two traded throws, and Sutton gained the advantage by knocking Figg from the stage with a hard body shot. But gradually Figg wore his challenger down, battering him unmercifully until he was forced to submit.

The final stage of the combat was conducted with cudgels, and since stick-fighting had always been Figg’s specialty, he wasted no time in reclaiming his coveted title, bringing the fight to a close by busting Sutton’s knee.

In the end, following the third and deciding meeting of the fighting pair, which Figg won, and Sutton elected to retire from the sport.

Meanwhile, Figg’s academy continued to flourish and was held in the highest esteem, establishing him as a man of some significance among the champions of fist, stick and sword. Around 1730, Figg also decided to give up fighting, and having fashioned a number of exceptional protégés within the various divisions of self-defence, decided to rely upon a trio of his most celebrated students, Bob Whitaker, Jack Broughton and George Taylor, to bring in the spectators and hard cash.

- George Taylor

George Taylor

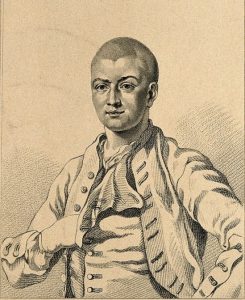

George Taylor [1716-1758] was known as ‘the Barber’, and was backed by Frederick, Prince of Wales, KG [1707-1751], the heir apparent to the British throne from 1727, until his death from a lung injury at the age of 44.

Taylor began boxing at Figg’s academy in 1730, where at the tender age of 14 he was a favourite amongst the patrons. Strong and skilful, he was a hard hitter, but short on courage. Following the death of his mentor Figg, in 1734, Taylor took over Figg’s amphitheatre, at the same time he laid claim to the coveted title of champion of England. He later went on to develop his own amphitheatre, where he trained boxers, and from time to time fought there himself.

In 1736, he lost the title of champion of England to Jack Broughton, who became the most famous of Figg’s pugilistic trio, but reclaimed it five years later following Broughton’s retirement from the ring. In 1743, Broughton came out of retirement and reclaimed the Championship of England title after Taylor cancelled a scheduled fight with him. Taylor closed his amphitheatre the following year, and went to work for Broughton at his London arena, where for six years he took on all-comers and won every fight.

He finally reclaimed the title of champion of England in 1750, when the grandson of James Figg, Jack Slack refused to fight him. Slack, who was remembered as being a savage, dirty fighter, had previously defeated Jack Broughton to become the champion. Slack is also credited with inventing the ‘rabbit punch’, and as being the first person to fix a prize fight. Taylor retired in 1751 and became the landlord of the Fountain Inn, In Deptford, London.

Jack Broughton

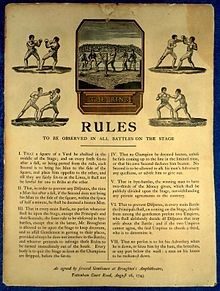

In 1743, Jack Broughton [c1703-04 – 1789] was the first to codify a set of rules to be used in ‘bare-knuckle’ contests. Prior to which the ‘rules’, such as they were, were carelessly defined, with a tendency to vary from contest to contest. His seven basic rules were observed at his own London amphitheatre, the largest and most influential of the time, which he opened with the help of a number of wealthy patrons, in Hanway Road, near Oxford Street, where Broughton and his team staged boxing exhibitions.

- Broughton’s rules

Broughton’s set of rules were regarded as definitive for around a century, and were later incorporated into the London Prize Ring rules. A list of boxing rules promulgated in 1838, based on those drafted by Broughton which governed the conduct of prize-fighting and bare-knuckle boxing for over 100 years. They introduced measures that remain in effect in professional boxing to this day, and are widely regarded as the foundation of the modern sport of boxing sport, prior to the development of the Marquess of Queensberry rules in the 1860s.

In 1750 Jack Broughton fought Jack Slack, and after just 14 minutes of the fight, was rendered unable to see as a result of a blinding punch delivered by the savage Slack. As a consequence he was forced to retire from the bout. Broughton’s patron at the time was Prince William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland [1721–1765], the youngest son of King George II, who it is said lost thousands of pounds on the fight. Shortly after the fight Broughton closed his amphitheatre, and instead ran an antiques business.

- Jack Broughton v Jack Slack

Broughton was one of the original inductees of the International Boxing Hall of Fame, in recognition of his contribution as a pioneer of the sport.

Bob Whitaker

About this time Figg decided to retire from competitive fighting, and the pugilistic world was up in arms, following a spate of insolent threats delivered by a massive Italian, Tito Alberto di Carini, who boasted he would break the jaw-bone of any opponent with the audacity to challenge him.

In 1733, after watching the gigantic Venetian defeat three men in a single night, the first Earl of Bath, William Pulteney [1684-1764], decided the honour of the nation was at stake and needed to be upheld. The fighting Figg was the obvious choice to send the gondolier back to Venice with a flea in his ear. But as Figg had since retired from active combat, he assigned the role to, Bob Whitaker, one of the students of his academy.

A terror among his fellow countrymen, the Venetian was a man of prodigious strength, whose fame preceded him. Enhanced by the alleged number of broken jaw-bones he had doled out to those foolhardy enough to oppose him, subsequently despatched to surgeons to be reset, he was considered a favourable gamble, and the match was made.

‘That ‘ere’s truth about his breaking so many of his countrymen’s jaw-bones with his fist’, pronounced Figg. ‘Howsomdever, that’s no matter, he can’t break Bob Whitaker’s jaw-bone, if he had a sledge-hammer in his hand’.

On the day appointed for the battle to take place, a large crowd gathered at Figg’s amphitheatre, crammed with nobility, stuffed with cash, among them King George II. The stage was cleared, and the Venetian made his entrance, greeted by his countrymen with loud applause. Beaming with confidence, he began to strip off, his giant-like arms and overall size, striking nervous unease among the spectators. A few seconds later, Bob Whitaker appeared and was also met with a roar of approval. Cool and calm, Whitaker, was an athletic man, an awkward boxer, celebrated for throwing and pitching his thickset body on top of his downed adversary. Eying the Gondolier firmly and confidently, he threw off his clothes, and in an instant the first attack commenced.

The gondolier opened with a blow to the side of the head which pitched Whitaker off the stage. And with wagers running high, the Venetian’s supporters cheered loudly, flattering themselves that Whitaker would be unable to come back from the desperate blow and the heavy fall he had suffered. Taking no more time than was necessary, Bob quickly recovered from the knockdown, and jumped back on the stage to renew the attack.

- Bob Whitaker v The Venetian Gondolier

With sparring now at an end, Whitaker decided something had to be done to render the Venetian’s long arm useless, or lose the fight. Without hesitation, he hunched forward and ran boldly in, and with one vicious body shot brought di Carini to his knees. The Venetian was quite sick, and with the tables now turned, Bob proceeded to ruthlessly punish him. Perplexed and confused for the next few rounds, the Gondolier was compelled to concede. In spite of his vanity, the Italian retired in disgrace, the vicious blow to the stomach proving too much to bear, bringing the first international prize-fight to an end, much to the dismay of his long-faced supporters.

Although illiterate, Figg was an astute promoter, and within a week had used Whitaker’s national triumph to set up another fight between Whitaker and another of his eminent students, Nathaniel Peartree. And on the day appointed for the fight the amphitheatre was once again stuffed to capacity.

Famous for his powerful blows to the head and face, it was said Peartree was a match for any man, and the odds were such that Whitaker’s earlier laurels seemed destined to be of short duration. Within six minutes, after carefully avoiding Whitaker’s attempts to go into a clinch and set up his throws, Peartree had targeted Whitaker’s eyes, closing both tightly shut, so that he was completely at the mercy of his opponent. He was forced to concede, grumpily complaining, ‘Dam’ me, I am not yet beat, but what signifies when I cannot see my man !’

Figg bet heavily on Peartree to beat England’s new champion, and duly collected, when Peartree won easily within ten minutes.

By this point in time, Figg was pushing 40, and his career as a fighter was at an end. A familiar sight around the streets of the West End, he was enormously famous and remained a popular hero and successful promoter.

Sadly, in December 1734 the following notice appeared in the newspaper. ‘Last Saturday there was a trial of skill between the unconquered hero Death on the one side and ‘till then the unconquered hero Mr. James Figg, the famous prize-fighter and master of the noble science of defence on the other. The battle was most obstinately fought on both sides, but at last the former obtained an entire victory and the latter, tho’ he was obliged to submit to a superior foe yet fearless and with disdain, he retired and that evening expired at his house in Oxford Road’.

Figg is buried in St. Marylebone Parish Churchyard.

Long was the great Figg, by the prize-fighting swains,

Sole monarch acknowledged by Marybone plains,

To the towns far and near did his glory extend,

And swam down the river from Thame to Gravesend

Article © Roy Case