The first recorded bare-knuckle boxing match was held in England in 1681, and although such bouts were judged illegal, within a few years contests were frequently being fought in and around the city of London. Impoverished fighters would scrap for whatever purse they could agree, more often than not supplemented by the added incentive of side stakes, while eager crowds of spectators wagered substantial sums on the outcome.

Bare-knuckle pugilism reached its peak in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, some time before the Marquess of Queensberry Rules were adopted in 1867. Consequently, the rules applied to bare-knuckle bouts were simple and few in number.

- Fights were fought using bare fists.

- Kicking, biting, gouging, and elbowing was not allowed.

- Grappling and throws were allowed above the waist.

- A round was ended when one fighter was knocked down.

- Fighters were given 30 seconds to rest, before the next round began.

- There were no judges assigned to score the fight.

- The fight was ended when one of the fighters was knocked unconsciousness, or when a fighter conceded defeat.

There were no weight divisions, and as such only one recognised English champion, consequently heavier men enjoyed a distinct advantage. Although it was common practice for fights to continue until one of the fighters was unable to carry on, on rare occasions a fixed number of rounds was agreed.

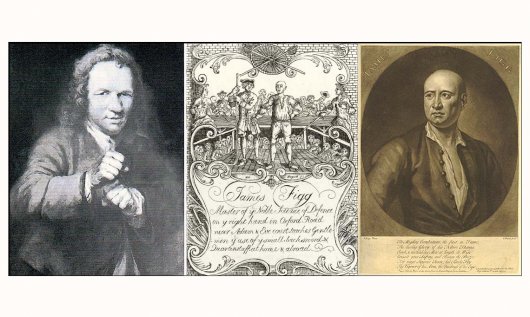

The first bare-knuckle champion of England was a bull-necked brawler named James Figg [1684-1734]. Born in Thame in Oxfordshire, Figg won the title in 1719, before bare-knuckle boxing truly came into its own. He fought during an age when a fighter would incorporate amongst his defensive skills the use of foils, cudgels and quarter staffs, with bare-knuckle fighting just one speciality numbered amongst the rest.

- James Figg

Figg retained the title for 11 years until his eventual retirement in 1730. It is claimed he fought a grand total of 270 bouts, losing only once in 1727 when he came up against a Gravesend pipe-maker named Ned Sutton, who beat him to win the English title. The 6ft tall Figg immediately demanded a re-match which he won to re-claim the Championship.

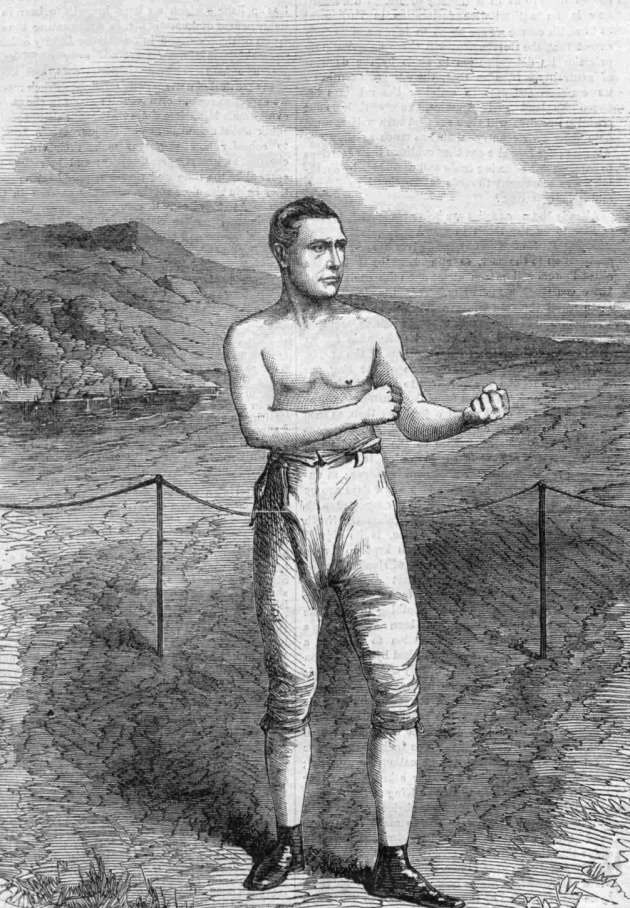

Nicknamed ‘the Gypsy’, bare-knuckle boxer Jem Mace [1831-1910] had the longest professional career as a fighter, lasting more than 35 years, until he was well into his sixties, his last exhibition bout coming in 1909 at the age of 79.

- Jem Mace

According to 19 century historical boxing records, the African-American bare-knuckle fighter Thomas Molineaux was born into slavery in the State of Virginia in 1784. Where it is claimed he fought other slaves to provide entertainment for the plantation owners. He was seemingly granted his freedom, along with the generous sum of $ 500, after winning a fight on which the son of a plantation owner had wagered the mind-boggling sum of $ 100,000.

After obtaining his freedom Molineaux moved to New York, where he fought several bare-knuckle bouts, eventually progressing to become recognised as the ‘Champion boxer of America’. Provisionally financially secure, Tom took the decision to move to England, anticipating he would be able to earn a comfortable living there as a prize-fighter.

On arriving in London in 1809, he made contact with another former slave and ex-boxer, Bill Richmond [c1763-1829], who ran the Horse and Dolphin pub, just off Leicester Square. Born a slave in Cockhold’s Town, Staten Island, New York, Richmond was the first African-American fighter to gain prominence in British bare-knuckle boxing.

Richmond started life badly. During his enslavement he endured all manner of unpleasant jobs, including that of an executioner. He moved to England in 1777, where he went through school thanks to the generosity of his benevolent employer Lord Hugh Percy, the Duke of Northumberland, an unusual gesture at a time when black man-servants were seen as a ‘must have’ fashion accessory for English gentlemen. A general in the British forces in New York during the American War of Independence, Lord Percy took a shine to the youngster after he learned how Richmond had single-handedly flattened a group of English Redcoats in a tavern brawl and engaged him as a servant. No longer a slave, Lord Percy even arranged for Richmond to be apprenticed to a local cabinet-maker in York. And in 1791, Richmond married a local English woman in Wakefield, who bore him several children.

- Lord Hugh Percy, the Duke of Northumberland,

While residing in Yorkshire, Richmond fought and won 5 boxing matches, defeating ‘The York Bully’ Frank Myers, George ‘Dockey’ Moore, two unnamed soldiers, and an unknown blacksmith. It was the colour of Richmond’s skin that rankled local brothel-keeper Frank Myers, who was angered when he saw Bill in the company of a white woman. Such were the ferocity of the insults that arose, the 200 lb blacksmith and the athletic Richmond agreed to settle their differences in a bare-knuckle bout. Although Richmond was 25 lb lighter in weight, he was the much more accomplished fighter, and the blacksmith was no match for the ex-slave and was well beaten.

In 1796, when on a visit to York races, a renowned local bruiser and fearsome brawler, ‘Dockey’ Moore, also upset Richmond and an on-the-spot fight broke out. Outweighed by a good 40 pounds, Richmond comfortably thrashed Moore into submission. Bill’s only reward being a few coins collected from the crowd, and the judicious attention of an aristocratic, rake and wastrel Thomas Pitt.

The stylish and well-read Richmond continued to suffer relentless racial abuse while living in York, and by 1795 he and his family had moved to London, where he became an employee and household member of the British peer Thomas Pitt, the 2nd Baron Camelford [1775-1804], whose attention he had attracted at York races.

- Thomas Pitt, the 2nd Baron Camelford

A boxing enthusiast and prolific gambler, Pitt may well have received some boxing and gymnastic instruction from Richmond, and it is said the pair visited numerous prize fights together. Pitt saw the opportunity of basking in Bill’s reflected glory, as well as the undoubted additional benefit to be accrued from some lucrative wagers. And since almost all aspiring early 19 century professional sportsmen needed a patron to invest in their talent, Bill readily accepted payment to meet the expense incurred in his fight to become a credible challenger for the title ‘Champion of England’.

Richmond lived the best part of his life in England, where he fought all 19 of his bare-knuckle contests. Losing only twice, his position as one of the greatest of English pugilists was assured. On two occasions he is known to have exhibited his skills for the pleasure of visiting European royalty. And as one of the most respected and admired of instructors, was honoured to be selected as an usher at the coronation of King George IV in 1821, following which he received a letter of thanks from Lord Gwydyr and the Home Secretary Lord Sidmouth.

Tom Molineaux learned a sort of English pugilism, in order to fight in the fierce bouts slave owners arranged between their slaves. He began his notable fighting career in Britain in 1810, and although he lost both fights against the widely viewed ‘Champion of England’ the mighty Tom Cribb, it was these bouts that brought fame to the former slave.

To read Part 2 Click HERE

Roy’s comments about early boxing rules heavily oversimplify Jack Broughton’s rules of 1743. Much of their concern was to establish a clearly structured match on which gambling could take place. So at least two rules were concerned with the settling of possible disputes. Roy is correct to say there was no referee awarding points, but before the match the competing sponsors or boxers selected two ‘umpires’ to settle disputes. The wording says ‘That to prevent disputes, in every main battle, the principals shall, on the coming on the stage, choose from among the gentlemen present two umpires, who shall absolutely decided all disputes that may arise about the battle; and if the two umpires cannot agree, the said umpires to choose a third, who is to determine it’. This was very similar to arrangements made in horse racing and cricket.

How much would Roy plays poker chip cost now

Anyone know anything about metcalf brown from lancs ?

He worked as a butcher and also did bare knuckle fighting