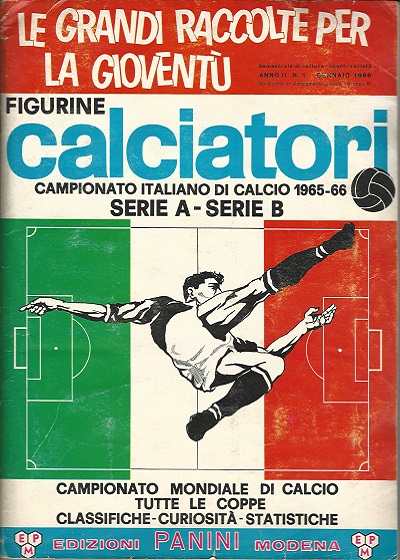

In the century of image and mass sports, it was not a matter of “if”, but rather “when”, somebody combined the power of football with the power of pictures, igniting a prosperous business and a global love story, propelled by the passion of children of all ages. In early 1960’s, Italy had just escaped the dire straits of the post-war years and found itself right in the middle of the “economic miracle”, the prolonged economic growth which turned the country into an industrial power. A pair of brothers from Modena, Giuseppe and Benito – the name of the latter revealing that their births dated back to the period of Mussolini’s regime – purchased an unsold lot of “Serie A” players’ stickers and then re-sold them in packs of four. Created by the economic boom, the new consumers, hidden in any soccer fan, bought more than 3 million packs, which allowed the industrial production of the stickers to begin and flourish. In 1961, the first album produced directly by Panini Company came out.

The editorial project relied on many of the typical factors which made the rapid growth of the Italian economy possible: the whole and rather numerous family were committed to their goal, the four brothers all involved at the enterprise in top-positions (it does appear that the four sisters were kept to one side, except for, arguably, sharing the sudden wealth), the artisan-like creativity, which led the brothers to mix the stickers and pack them in a container originally designed for making butter together with the connection to a local network of small and medium-size industries, saw the pivotal role that the packaging played, which in the early days was carried out by female home workers (rewarded with the usual low wages), which, according to an organization model, was quite popular and effective in the clothing and textile sector.

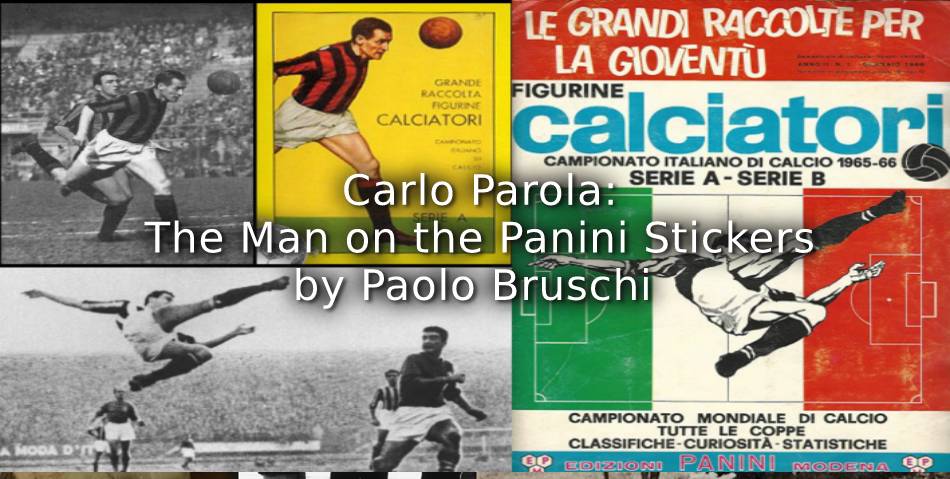

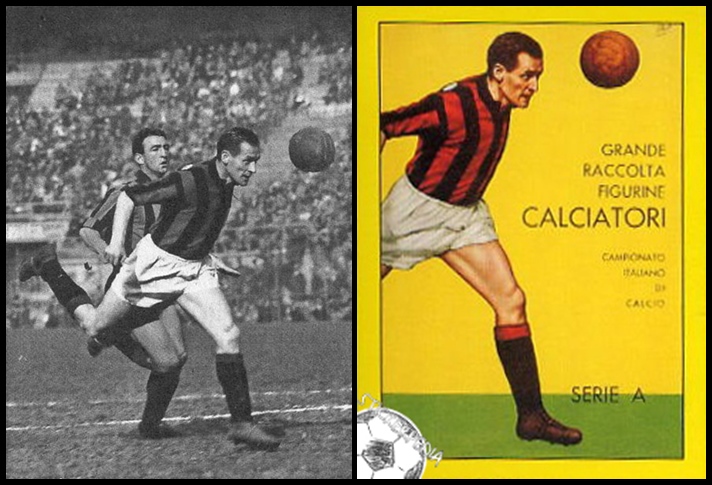

In 1961-62, the first “Great Collection Calciatori Stickers” had on its cover Nils Liedholm, wearing his red and black Milan jersey. The refined Swedish mid-fielder, winner of an Olympic gold medal at London, 1948 and runner-up to Pelè’s Brazil in the Rimet Cup, played on his home soil ten years later, had just stopped playing and was best known as member of the celebrated trio “Gre-No-Li”, along with country-fellows Gunnar Gren and Gunnar Nordahl. The image on the cover was not a photograph, but a drawing from an existing picture of the player. A few years later, in 1965, Panini put on the album cover the image of another player, caught in the very moment of executing a spectacular over-the-head bicycle kick, which was so amazing to see, as the action still is today, which soon became the Panini logo. The player was Juventus defender Carlo Parola and, along with Nils Liedholm, shared the same inclination to sportsmanship and the same elegance and gracefulness in his style of play. Following an already established pattern, the acrobatic image was a drawing from a snapshot, which was taken on January the 15th, 70 years ago.

In Florence, Juventus took on Fiorentina as the most important game in the first day of the 1949-50 second-round championship. In the opinion of the leading reporters who watched the match, it was nothing worth, except for a late penalty kick missed by the young Florentine Sergio Cervato and a majestic performance from Parola. In the words of Vittorio Pozzo (who had re-invented himself as a journalist at “La Stampa” in Turin, after having led Italy’s national team to victory in the 1934 and 1938 FIFA World Cups as a coach, and also to a gold medal at the 1936 Olympic football tournament), the black-and-white defenders played such a dominant game that he had to be considered in the best shape of his entire career, especially for his noticeable high-quality skills and cool command. He was also full of energy, as testified by his famous flying bicycle kick, “which had the effect of putting an opponent off his stroke, the ball being whipped away from under his nose when he thought he had full control of it”, as Parola himself once described his trademark play.

That afternoon, the magnificent kick was captured for eternity by a Florentine photographer named Corrado Banchi, who in his way confirmed Democritus’ statement, that everything in the universe is the fruit of chance and necessity. Banchi was not given a satisfying position from which to capture memorable images. During the second half, he had found himself in a slight quandary when he needed the toilet but was unable to leave the field of play, so he decided to take advantage of the 3,000m steeplechase water jump pit! Consequently, he found himself right behind the Juventus goalkeeper when a long range cross fell in the black-and-white penalty box. Before any Viola striker could even think of hitting the ball into the back of the net, Parola imperiously took flight and rose into the sky, a perfect gesture in midair, in a unique style. Banchi was quick and lucky enough to release the shutter just a few moments after the ball was kicked, that gave the resulting picture a sense of power and animation. It seemed no big deal to Banchi, as he rushed to the newspaper and collected his 3.000 lira for copyright fees. Not a huge amount of money (about 60 euros today) for a picture which will be reproduced billions of times. Although it didn’t appear on all of the Panini album covers after 1965, it has always been stamped on the packs and all the children who performed the “Got-got-need” ritual, had to rip up the ubiquitous iconic image first, most likely completely ignoring the identity of the depicted player.

Carlo Parola was born in Turin in 1920 and turned to football after a period as a cyclist. He got a job at FIAT, the Italian automobile manufacturer based in Turin, and began to play for the factory team, from where he jumped into the Juventus squad in the late 1930s, greatly multiplying his salary and almost causing his mother to have a heart attack! Despite winning just 10 caps for the national team (the last one at the 1950 World Cup, when Italy failed to qualify for the knock-out stage), he deserved some international recognition after being selected for the “Rest of Europe” XI, who faced Great Britain to mark in emphatic fashion the return of the four UK football associations to FIFA. On May 10, 1947, in front of 137.000 fans at Hampden Park and with Stanley Matthews sparkling on the right wing, Great Britain, wearing Scotland’s dark blue strip, humiliated the continental side, by netting six goals and conceding just one. In spite of this demolition, and even an own goal due to a communication foul-up with the French goalkeeper, Carlo Parola was regarded as a great defender and afterwards Chelsea offered him £15,000 only to be refuted.

- Parola and Nordahl

Parola himself considered his performance in Scotland the best in his life and proof of his fine soccer prowess. Antonio Ghirelli, who in the 1950s wrote the first real history of the game in Italy [30 years later he would become the chief press officer for the Socialist President of Italy, Sandro Pertini and then for Prime Minister Bettino Craxi], wrote in his Storia del calcio:

“The man of Glasgow, as he came to be called, effectively represented the most complete example of the third-back defender […] Tall, slim and robust in person, alien to any harshness in contact, more inclined to the acrobatic and the elegant, rich in commitment and fair play, master of ball control like few others, and always looking for the constructive pass, rather than the hasty clearance, you couldn’t name a player more harmonious than Parola. His weakness, naturally exacerbated by his physical decline, lay, if anything, in an excess of sportsmanship, and in a certain elegant exhibitionism, both prejudicial defects in the modern game”.

Parola played over 300 games for Juventus between 1939 and 1954, winning two Serie A titles and a Coppa Italia, and served as club captain from 1949 onwards. In the mid-1970s, he returned to his beloved black-and-white colours as a coach, adding one more Scudetto before vacating his post for Giovanni Trapattoni’s 10-year-tenure.

Article © Paolo Bruschi