Before the Second World War football contacts between Yugoslavia and United Kingdom were week and sporadic and football played by the two nations was regarded to be quite different in style and quality. But, nevertheless, through the entire interwar period, Yugoslavs admired the British for their passion for the game, for the organization of their clubs and for the importance football had in their social life. Yugoslav sports newspapers were full of reports from matches of English and Scottish championships, football enthusiasts had their favourite teams and the advantages and disadvantages of WM formation was discussed. Football public in Yugoslavia always wanted to see a direct confrontation between the two football cultures but because of different circumstances this simply wasn’t possible until late 1930s, when two enthusiastic Yugoslav clubs, Gradjanski Zagreb and Jugoslavija Belgrade decided to try to organize tours of the British Isles.

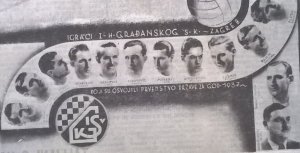

- Crest of Gradjanski Zagreb

Gradjanski was one of the most successful Yugoslav football clubs in the interwar period. It was always very much focused on international acclaim, appearing in Mitropa Cup and playing numerous international friendlies. But the pinnacle of Gradjanskiʼs international success in those years was the match against Liverpool FC, played in Zagreb in spring of 1936. In front of the crowd of about 20.000 people, the largest ever seen at Gradjanski new stadium, home team managed to win 5:1, achieving one of the biggest ever victories of a Yugoslav club over any European side. Liverpool FC management immediately sought the opportunity for a re-match and invited Gradjanski to visit England in autumn the same year. Gradjanski officials accepted the invitation and eventually agreed on a 14-day tour of United Kingdom to be held in November 1936.

This proposed tour was arranged by Austrian sports journalist and agent David Weiss, with the help of English referee Walter Lewington, who apparently acted as Weiss’s partner and agent for United Kingdom. The tour represented a huge opportunity for Gradjanski to make an international name for themselves, but apart from the promotional value of the tour, the new club management, led by well-known and respected Hungarian coach Márton Bukovi, saw the tour as a chance to observe and learn the new techniques and tactics implemented by British football clubs. Bukovi was a typical protégé of the Central European school of football, emphasizing the importance of passing and technique, but he was also keen to learn and was aware of the potential positive influences of the tactical firmness which was characteristic for British football clubs. He was particularly interested to see how the Herbert Chapman’s WM tactic was working. This miraculous tactic was praised by continental journalists but was rarely put to practice by coaches and managers.

- Marton Bukovi with football fans

However, despite the big desire to go to United Kingdom, Gradjanski first had to overcome several organizational obstacles. Firstly, the tour was supposed to take place during the qualification round of the 1936/37 Yugoslav football championship, and the Yugoslav FA was very strict in its policy not to interrupt the competition for friendly matches and tours. Gradjanski had enough registered players to cover both the tour and the national championship and eventually the board of directors decided to send the first team to United Kingdom, hoping that the reserves would somehow manage in domestic competition. The second big problem was to get the approval from the authorities to travel ‒ they had to apply for permission with the Yugoslav FA. The YFA usually didn’t object to such schemes, as long as the national competition calendar wasn’t disturbed. The club had to submit all the details – who will travel, which cities are they going to visit, against whom are they going play, how much money was expected as profit, etc. The YFA gave the green light promptly. The second stage of the process was to get permission from the Yugoslav Ministry of the Physical Education, which was a slightly bigger problem, as the Ministry was scanning such proposed tours for potential political subversion. Gradjanski was not just an ordinary football club, but was also seen as one of the symbols of Croatian cultural and political identity in Yugoslavia, with strong ties with the opposition Croatian Peasant Party. But in this case everything went rather smoothly and the Ministry of Physical Education quickly approved the proposed tour, ordering the Zagreb police authorities to issue passports for players and other members of the delegation.

Gradjanski started their journey on 5th of November 1936 from Zagreb central railway station. Few hundred of their fans gathered to wish them farewell. The following footballers embarked on the journey: Emil Urch, Dragutin Bratulić, Bernard Hügl, Marko Rajković, Ivan Belošević, Josip Kovačević, Toni Pogačnik, Ivica Gajer, Gustav Lechner, Mirko Kokotović, Ivica Medarić, Branko Pleše, Slavko Šurdonja, August Lešnik, Milan Antolković, Aleksandar Tomašević and Nikola Perlić. They travelled by train to Calais and then by boat to Dover, by train from Dover to London and by train from London to Liverpool. After many difficulties they reached Liverpool on 9th of November, early in the morning, rather tired and exhausted. During their journey, Gradjanski played two training matches in Switzerland, beating FC St. Gallen and losing to FC Basel, failing to show inspired performance and to impress the spectators.

- Paying respects at Liverpool Cenotaph

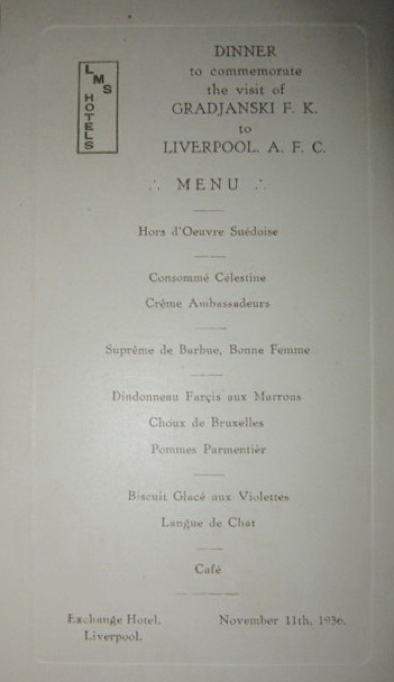

Upon arrival in Liverpool, Gradjanski players first rested a bit and then went to pay their respect to British soldiers killed in the Great War, by laying wreaths and flowers at the Liverpool Cenotaph. In the afternoon they had a training session at Liverpool stadium. They were delighted with the stadium and the training facilities, as most of them had never seen something like that before. The match between two teams was played in bad weather, in front of 10.000 spectators. Gradjanski tried hard to put up a fight but they only managed to lose 4:1. Liverpool was clearly the better team, but Gradjanski was still competitive in the first half, losing it 1:0, but beside being tired from the long journey, they had a bit of bad luck as well – one of the most important players Toni Pogačnik got injured 25 minutes into the match and for the most part of it Gradjanski played with only 10 men on the pitch. The reporters agreed that Gradjanskiʼs goalkeeper Emil Urch saved the team from experiencing a heavier defeat. Also, the British press had concluded that, despite the heavy loss, Gradjanski was an excellent team. After the match, Liverpool football club organized a banquet for the guests. Apparently, a lot of drinking and singing took place at the event.

- Liverpool FC v Gradjanski

- Official Dinner menu

The next match on the tour was against Doncaster Rovers, the bottom team of the Second division. The Yugoslav football public expected a comfortable win, but that didn’t happen. In fact, Gradjanski was unpleasantly surprised with a 6:4 defeat. Yugoslav footballers had underestimated Doncaster, whose players were fast and played down both flanks, creating chances easily. Yugoslav footballers were quite surprised with the fact that there wasn’t much difference in quality and approach to the game between the teams of First and Second division. Of course, the day ended with a jolly banquet.

The best performance in the entire tour Gradjanski gave in Edinburgh, in the match against Heart of Midlothian. In front of 10.000 people at Tynecastle stadium, Gradjanski had controlled most of the match, created lots of chances and converted those chances to goals easily. The first half ended with the 3:1 Gradjanski lead, but Scottish players showed more initiative in the second half and managed to score a goal from a dubiously awarded penalty-kick. Gradjanski once more extended their lead but Hearts pushed as hard as they could and in the end the final result was a 4:4 draw. The game was very entertaining and both teams were satisfied in the end. Ljubomir Vukadinović, prominent Yugoslav sports journalist who accompanied Gradjanski on their tour, later wrote that the match against Hearts was one of the most exciting in his entire career. The exciting day ended with a banquet, organized in honour of guests from Yugoslavia, starring Tommy Walker, prominent Hearts player, who entertained the guests by singing Scottish folk songs and club chairman, who accompanied him on the piano.

- Gradjanski players in Edinburgh

- Yugoslav newspaper reporting match between Gradjanski and Hearts

After Edinburgh, Gradjanski travelled to Wolverhampton, where they stayed for few days. The match between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Gradjanski was played in heavy fog, in front of only 2.000 spectators. In fact, the fog was so thick that the referee thought of postponing the match, but Gradjanski officials urged him to proceed, because they already had an arranged match in London. The match ended with 4:2 victory for the Wanderers, but that is all the Yugoslav reporter could telephone back to his office in Yugoslavia. To his own confession, the fog was such that he couldn’t even see who scored the goals, let alone what the match was like.

- Gradjanski players in training at Wolverhampton

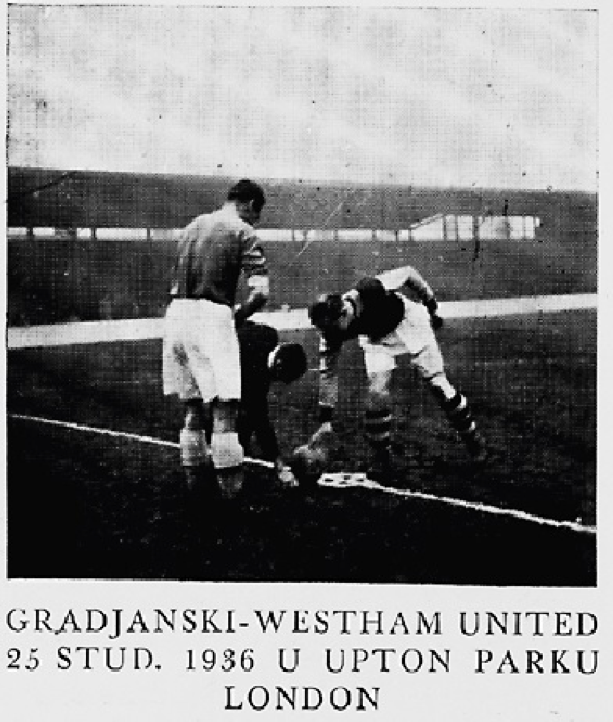

The final fixture of the Gradjanski tour was played in London, at Upton Park. West Ham United hosted the Yugoslavs in front of 2.000 people. This was, by unanimous verdict of both journalists and players, the worst performance of Gradjanski in the entire tour. West Ham won by 1:0, by an accidental fluke shot in the 5th minute of the match. Rest of the game was boring and without any proper chances.

- Gradjanski v West Ham United

Gradjanski delegation seized the opportunity during the tour to visit several other football clubs and watch few championship matches. They visited Everton, Aston Villa and Arsenal and had the opportunity to watch matches between Liverpool and Sheffield Wednesday and Aston Villa and Blackburn Rovers. These excursions left very strong impressions on the Gradjanski delegation. The reporter who accompanied the team described Villa Park as a „castle from a fairy-tale“. In Wolverhampton they had the opportunity to train with the home team, which gave them an insight into process of preparation for the match. Gradjanski had a terrible misfortune during the tour that they lost one of their best players, full back Gustav Lechner, to a knee injury. However, even this misfortune had a silver lining – during their visit to Liverpool FC, Lechner was used as a sort of a guinea pig for the hosts to show latest techniques in the field of sports medicine and physiotherapy. The players and the other members of the delegation were particularly impressed with what they saw at Arsenal – modern stadium, top level facilities, and orthopaedic infirmary, something that was simply unimaginable in Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav delegation also used the opportunity to see the sights of London and the players were especially keen to visit Madame Tussauds.

- Gradjanski players in front of Villa Park

According to the Yugoslav press and according to the testimonies of Gradjanski players who were involved in the tour, they gave the best they could in all the matches. After the tour, the club officials agreed that the overall performance was good, that Gradjanski didn’t give up in any of the matches and that the loss of Lechner proved to be the decisive factor, especially in the defensive line. After all, as the official statement from the club said – they didn’t go there to teach lessons but to learn a few. The club officials were also satisfied, although they expected more income and were unpleasantly surprised with low attendance at some of thefixtures. The fans however, were not that happy. They had clearly expected a positive balance at the end of the tour. Pompously announced, the mass welcome reception of Gradjanski players at the Zagreb railway station never happened. About the same number of people who escorted them to the United Kingdom, had welcomed them back.

Consequences of the Gradjanski 1936 tour of United Kingdom were significant and far-reaching. Bukovi, head coach of Gradjanski, started to implement WM formation, which led Gradjanski to the Yugoslav championship title in the 1936/37 season and making the team dominant force in Yugoslav football up to 1941. Also, Bukovi adapted WM formation and created a sort of hybrid, the so-called WW formation (4-2-4). During 1950s, he worked as an assistant to Gusztáv Sebes, coach of the Hungarian national football team, and his tactical ideas were widely accepted by the Mighty Magyars, one of the best teams in the history of the world. Most importantly, by visiting the cradle of football and playing against British teams, and by not embarrassing themselves, Gradjanski had acquired a prestige among the Yugoslav football fans no other club could match for a long time.

- Gradjanski – Yugoslav Champions for 1937

Article © Dejan Zec