Read the earlier parts of this series

Part 1 – HERE , Part 2 – HERE and Part 3 HERE

The documents images (starting from the letter by Antonio Sams) are taken from:

Milano, Archivio di Stato di Milano,

Questura di Milano, Divisione I – Gabinetto, b. 165, cat. A3B, fasc. 094, Casellario giudiziario

These images are published with the permission by Ministero dei Beni e le Attività Culturali.

Any reproduction of images is forbidden.

What happened after 1945 to those Italian women eager to play football? After reading the history of the brave 1933 Milanese calciatrici ‘women’s footballers’, who were first helped but then boycotted by the Fascist regime, one might guess that after the end of World War II and the restoration of democracy, there was no problem for them. But they soon discovered that only the surface layer had changed: the inner male-dominated part of Italian society remained the same. Football was still was a man’s sport, no women should play: so – exactly as it was in the 1930s’ … – those who played it were judged as deviant women, or they were allowed to participate because of their showgirls’ extraordinary status (see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/playing-football-with-the-chorus-girls-vaudeville-womens-football-in-naples-1931/ ).

Until 1945 the Italian Olympic Committee (CONI), which supervised (and still supervises) every single sport Federation, was the sidekick of the Fascist regime in assisting the “right” while boycotting the “wrong” women’s sports: after carried on working after 1945, but now in the pay of the democratic parties, with the same narrow minded attitude towards women’s football.

In this video about the 1946 match at Stadio Flaminio, Rome, you can see a vaudeville football match

The actresses’ team vs. the dancers’ team, wearing AC Roma and SS Lazio shirts

Alberto Sordi is among the audience.

When the players enter the field, the speaker says: ‘The girls enter at a trotting pace: what a parade worthy of the best racehorses tradition’!

Source: http://patrimonio.archivioluce.com/luce-web/detail/IL5000094628/2/roma-stadio-flaminio-partita-calcio-attrici-e-ballerine.html

Due to the fall of the regime, there was important news: being calciatrici a sort of sideshow able to drawing crowds, several political parties tried to exploit it for their propaganda. On one hand, some local federations of the left-wing association Unione Italiana Sport Popolari (UISP) organized football matches between 1947 and 1948; on the other hand, in 1946 some matches were played all along with Italy between Triestina and Ragazze di San Giusto, in order to propagandize the Italian identity of Trieste, a city which was still disputed between Italy and Yugoslavia.

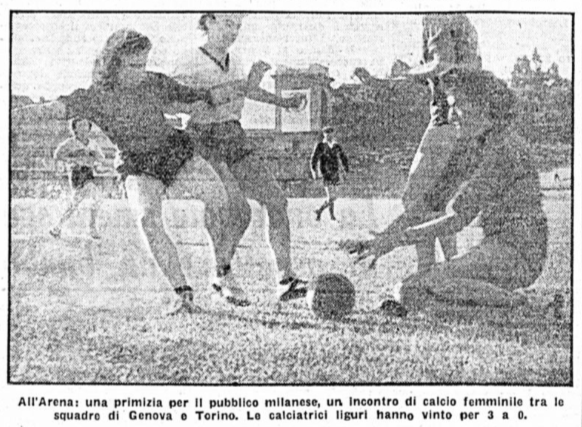

A 1947 match played in Milan between Genua and Turin, defined as ‘a delicacy for the audience’

Source: Corriere d’Informazione, 14-15 luglio 1947, p. 2.

The 1947 football match was an event linked to the beauty contest Stellina del Lavoro, organized by left-wing trade union among female workers.

Source: Archivio Storico della Camera di Lavoro, Bologna, https://bologna.repubblica.it/cronaca/2014/06/28/foto/tu_scioperi_io_ti_licenzio_il_prezzo_pagato_dalle_operaie_negli_anni_50-90212551/1/

The only one known picture of 1946 calciatrici from Trieste

Although we know very little about the 2 teams, we can notice that a female (unlike 1933) is the goalkeeper …

Source: https://sport.sky.it/calcio/approfondimenti/1945-checkpoint-trieste-programmazione-sky-sport

Luigi Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic, visits Trieste on the occasion of the definitive re-annexing of the city to Italy (1954)

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Questione_triestina

Thanks to Giovanni Di Salvo’s book Quando le ballerine danzavano col Pallone (2014) and to Francesca Tacchi’s article Calciatrici malgrado tutto (2020), we can reconstruct the major events in women’s football from 1946 to 1949, and then from 1958 to 1959.

In the first period, there were three important teams, all from North-western industrial cities, such as Turin, Genua, and Alessandria.

Alessandria – Torino match highlights (April 1948): the first team is wearing white shirt, the second the traditional granata ‘garnet red’ shirts. In the very first second, the director focuses on … the calciatrici legs, while the speaker sighs: ‘If only they allowed us to be their masseurs …’ Source: https://youtu.be/xyrQJtKJ5Mk

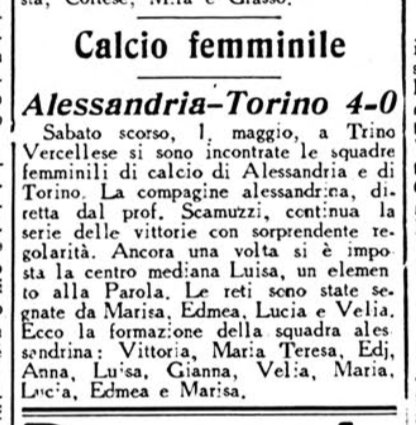

In Spring 1948, the Alessandria team defeated the Turin team 4-0

Note that that the journalist calls the players by their first names only, probably either to protect the girls’ anonymity, and/or to depict them as young girls

Source: Il Piccolo, 08/05/1948, p. 4.

As reconstructed by Giovanni Di Salvo, the Alessandria team was founded by Edmea Rossanigo, a worker of Borsalino, the world-wide famous luxury hat company: she and some colleagues were guided by trainer Piero Scamuzzi.

Alessandria, season 1948/1949. Note the ‘Borsalino’ sponsor ad on the shirt

Source: https://twitter.com/ContropiedeRosa/status/1150728172796829697

A 1949 Borsalino ad

Source: https://bit.ly/3vR9hh3

A clipping from a local newspaper:

Amelia Piccinini, the famous athlete from Alessandria (and former calciatrice, in 1933) who would compete in 1948 London Summer Olympics (winning shot put silver medal, see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/playing-in-heeled-shoes-in-milan-and-winning-olympic-medals-in-london-some-new-discoveries-about-the-pioneers-of-italian-womens-football/ ) would join the local football team on her return from the UK.

Up to now, there was no historical evidence that she actually played in 1948

Source: Il Piccolo, 03/07/1948, p. 4

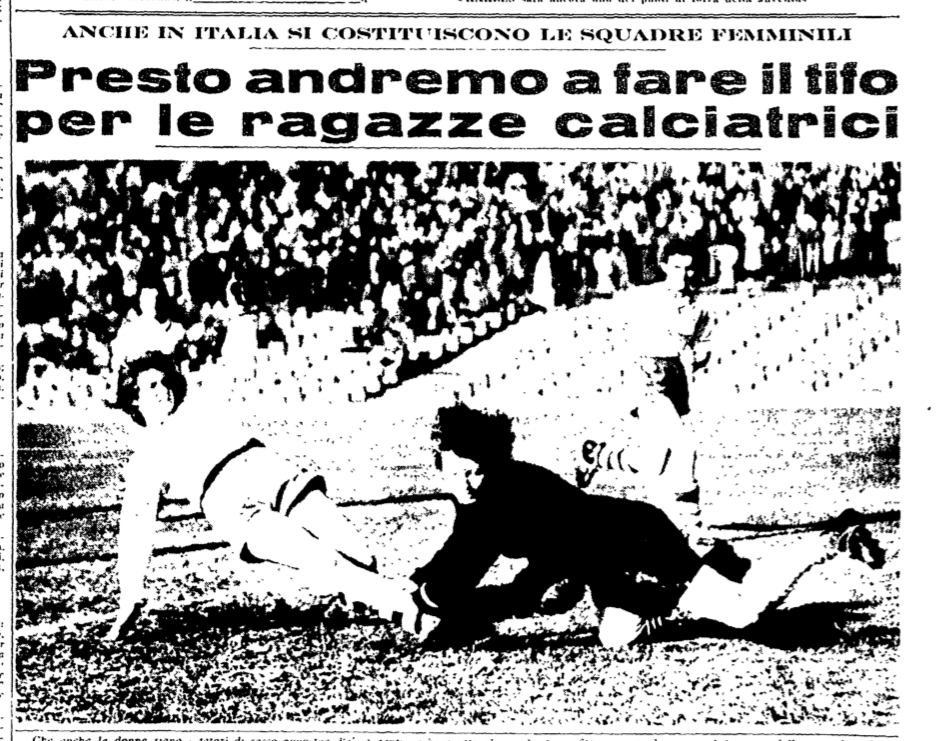

Ten years later, a Baroness from Naples (Angela Altini di Torralbo) tried to exploit women’s football for the Monarchical Party propaganda: she also founded Associazione Italiana Calcio Femminile (AICF), the first-ever Italian women’s football association. As recounted by Francesca Tacchi, in the summer of 1959 the CONI didn’t accept the affiliation of FICF’s (the new name of AICF: Associazione > Federazione), but also put pressure on the Ministry of the Interior, which issued a memo for all Italian Pretori and Questori: that no municipal sports field should be granted to the calciatrici. As happened in 1921 in the United Kingdom with the FA ban, removing access to the pitch was the key of the boycott.

An article about the foundation of AICF, in Summer 1958

Source: L’Unità, 4 agosto 1958, p. 6.

A match played in Naples between two local teams, Jolly vs. Amazzoni (June 1959). The lady with the flowers at the beginning of the video might be Baroness Angela Altini di TorralboSource: https://youtu.be/fASmXBZ6CRI

La partita fra romane e napoletane (luglio 1959). In July 1959, a match between a team from Rome and another one from Naples took place Source: https://youtu.be/nO0aFLL-w4o

The combined research using both archive and press sources can shed light on some hidden stories from the world of women’s football: because even in democratic Italy women were socially invisible and recovering their stories requires hard work. However, when interrogated the Milan Archivio di Stato gives up its hidden story …

Before talking about that, let’s start with the press sources. On Sunday 11 September 1949 a women’s football match was to take place in Bolzano (Bözen) at the local Stadio Druso. Due to a media campaign the previous day (a lot of posters were put on on Bolzano’s walls), a crowd duly gathered, waiting for the two opposing teams from Milan and Trieste. At 5pm only the team from Milan arrived, all together in two cars. The crowd was astonished at their appearance, were these women ‘guests of a sanatorium’? As a journalist wrote:

‘Teenage girls skinny as a toothpick and women in their forties fat like an overripe fruit desperately tried to kick an innocent ball, among jeers and jokes from the audience’.

Finally at 7pm, when the sunlight was fading, the second team from Trieste arrived, two hours later than expected: when a brawl broke among the players, the crowed turned hostile, with some asking and obtaining a ticket refund.

The façade of Stadio Druso, in Bolzano.

Note the dual-language (Italian and German) names during Fascist time, the Italian government tried to Italianize the German-speaking inhabitants of Bolzano and all the Alto Adige/Südtirol region, banning the use of German language.

Source: https://www.sentres.com/it/stadio-druso

Stadio Druso was inaugurated in 1931

An example of the sporting architecture of the Fascist Ventennio

Source: https://www.sentres.com/it/stadio-druso

Since not all the spectators got the refund, the two football match’s promoters were charged: a police inquiry discovered that Gaetano Olivieri from Fiume (today Rijeka, in Croatia, the hometown of the family of Mario Bonitta, calciatrice Luisa Boccalini’s husband: see https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/articles/football/and-then-we-were-boycottednew-discoveries-about-the-birth-of-womens-football-in-italy-1933-part-9/ ) and above all Bruno Gardina from Pola (today Pula, in Croatia) made a deal with some Trieste-Istrian-Dalmatian refugees living in camps in Milan and Vicenza: that they would be paid for playing football in Bolzano. No matter that almost none of them were able to play football: the main rationale of Gardina (who was living in Trieste) was to gather together 22 players. When Gardina reached Bolzano, he slipped away, leaving all alone Olivieri and the players, who were arrested by the police for their brawl, and then expelled from the city. Olivieri and Gardina’s legal troubles weren’t finished. In 1953 they were charged because they didn’t pay the Milanese car renters who allowed them to travel from Milan to Bolzano.

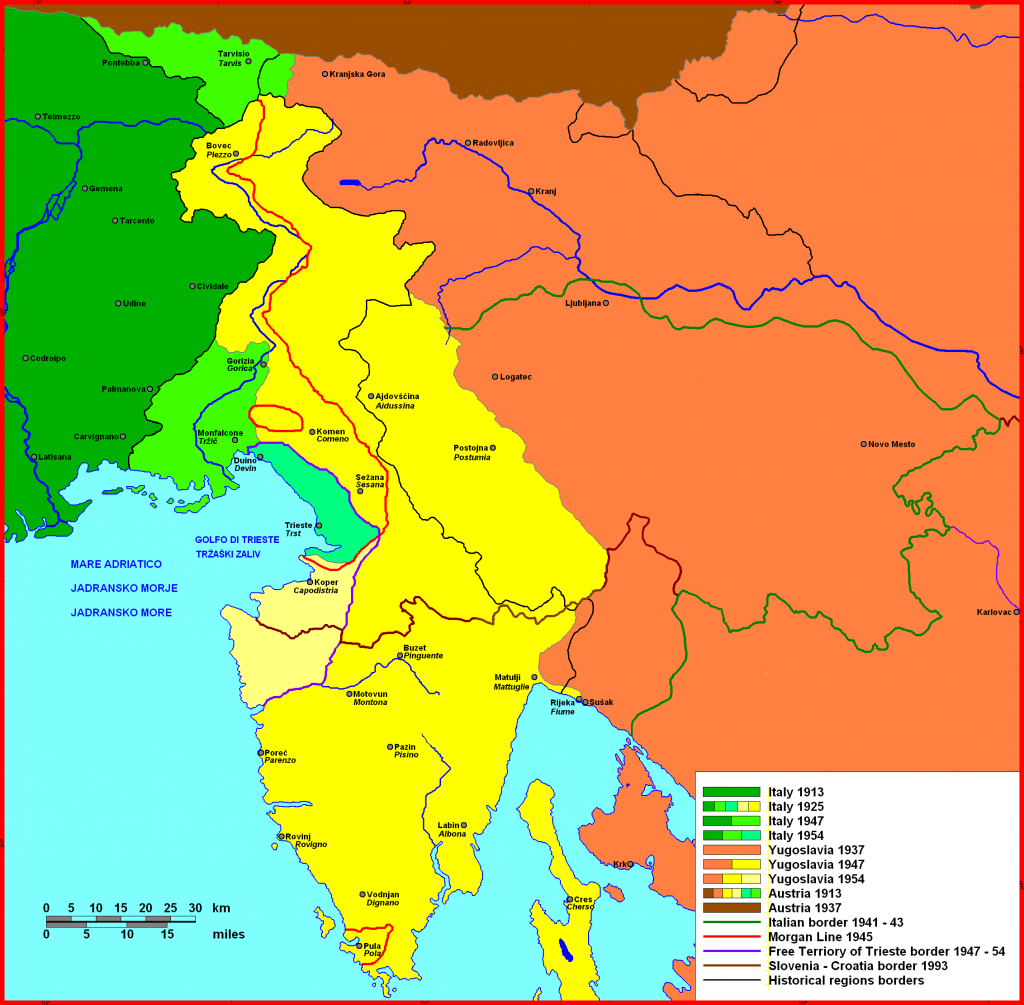

After World War II, Yugoslavia conquered the yellow zone (Istria and Dalmatia); the light-green area of Trieste was disputed until 1954.

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esodo_giuliano_dalmata

Italians leave Pula, 1947, on board of Toscana ships

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esodo_giuliano_dalmata

The 1949 Bolzano match is such a great example of men exploiting women’s sports for financial: in contrast to the stories relating to vaudeville women’s football, these players were not rich showgirls or professional dancers, but desperate refugees. The Milan Archive di Stato files offer more sources that allow us a glimpse into the painful atmosphere of the refugee camp in Milan, in the summer of 1948.

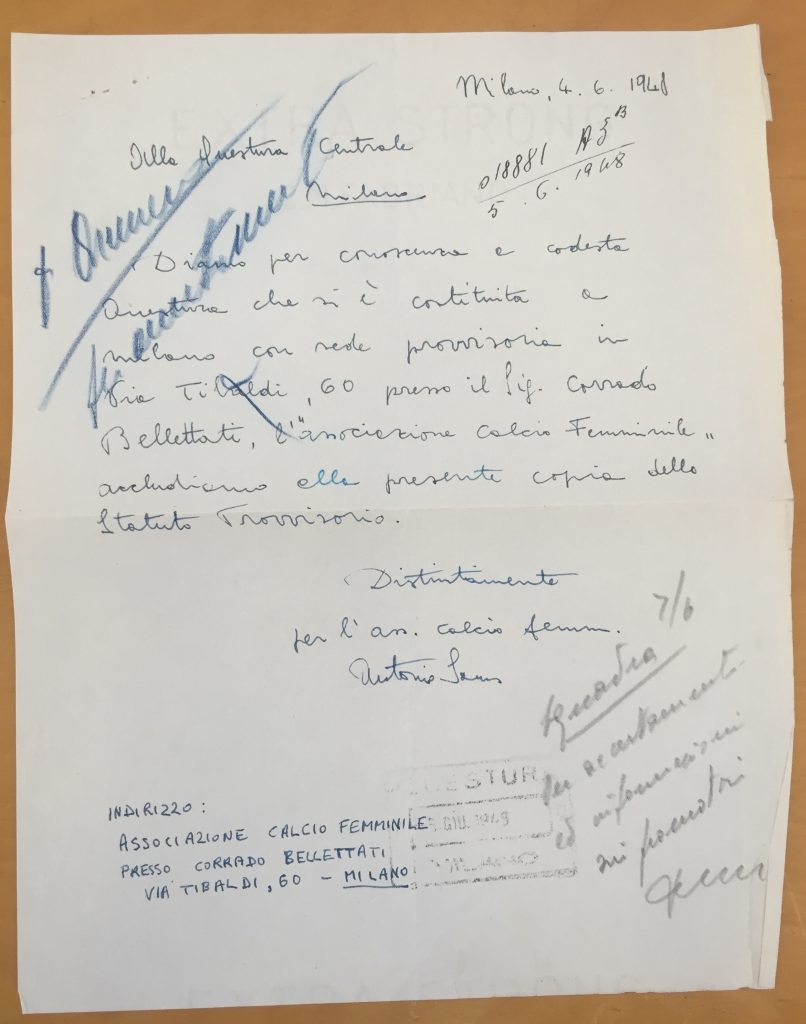

The letter by Antonio Sams to the Questura (04/06/1948).

On 4 June 1948, Antonio Sams wrote to the Milan Questura to let it know that Associazione Calcio Femminile (ACF) had been founded in Milan, with a provisional seat at Corrado Bellettati’s home, in Via Tibaldi 60. The attached ACF Temporary Charter is a very interesting document in order to understand the aims of the promoter.

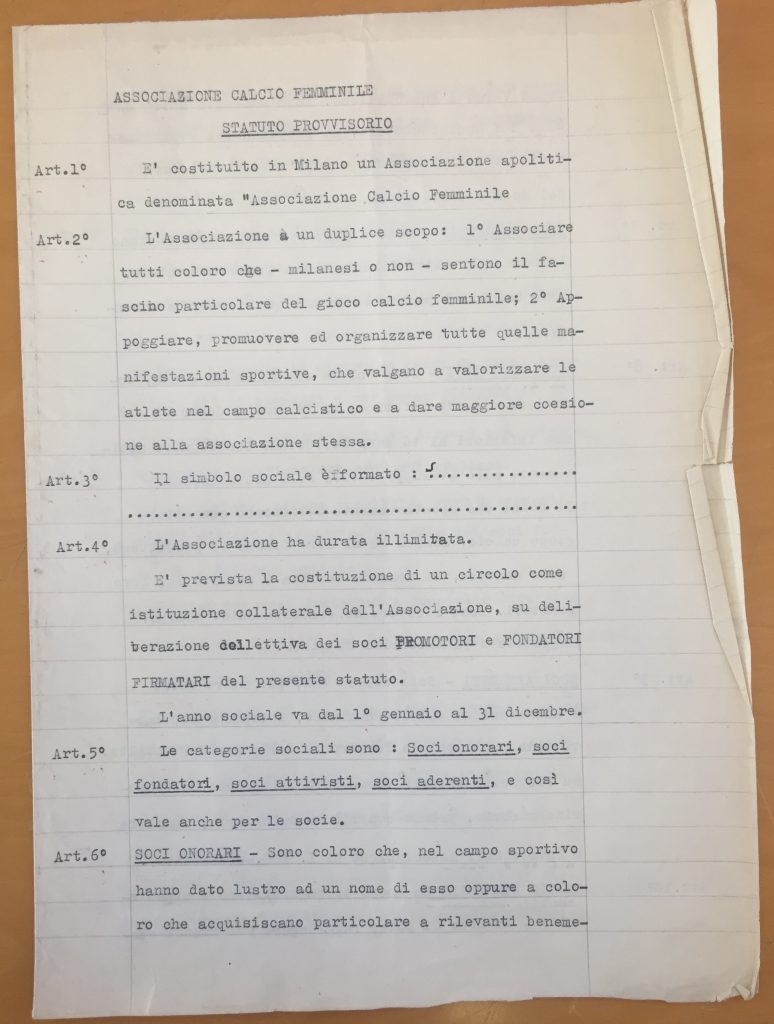

The 1st page of ACF Temporary Charter.

ACF, who claimed to be a ‘non-partisan association’ (art. 1), aims to 1) “associate those who – native of Milan, or not – are fond of women’s football”; 2) organize sports events for their athletes (art. 2).

The 2st page of ACF Temporary Charter.

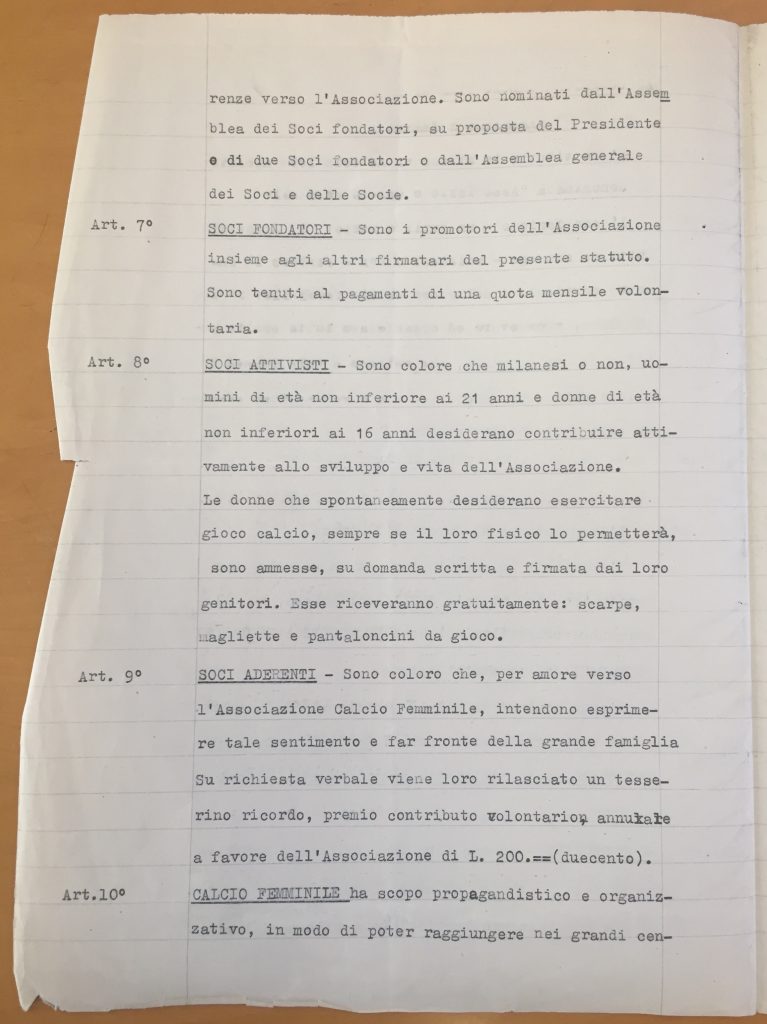

The Charter provides for 4 types of male and female members (art. 5): honorary members (art. 6); founding members (art. 7); active members (male older than 21, female older than 16) (art. 8); supporters (art. 9). According to art. 8, female players are young women eager to play football who would be accepted, ‘assuming that they are physically up to it and with the written request of their parents’: the same two conditions of 1933 Milanese GFC. ACF would provide the players with shoes, shirt and shorts for free.

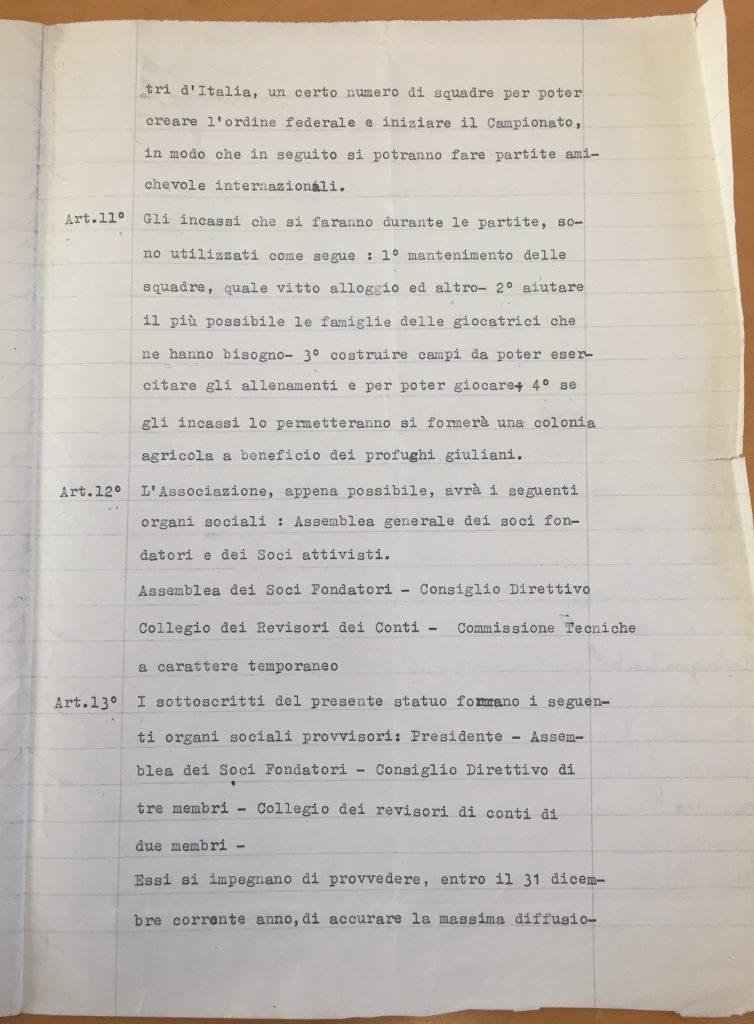

The 3st page of ACF Temporary Charter.

The ultimate AFC goal was to spread women’s football practice, in order to create a National Federation and a National Championship, and then international friendly games (art. 10). ACF takings would be used for 1) paying board and lodging for the players; 2) helping the players’ families; 3) building football fields; 4) building a farming colony for the Adriatic refugees (art. 11) – this point is really interesting, because it shows the hidden political profile of ACF…

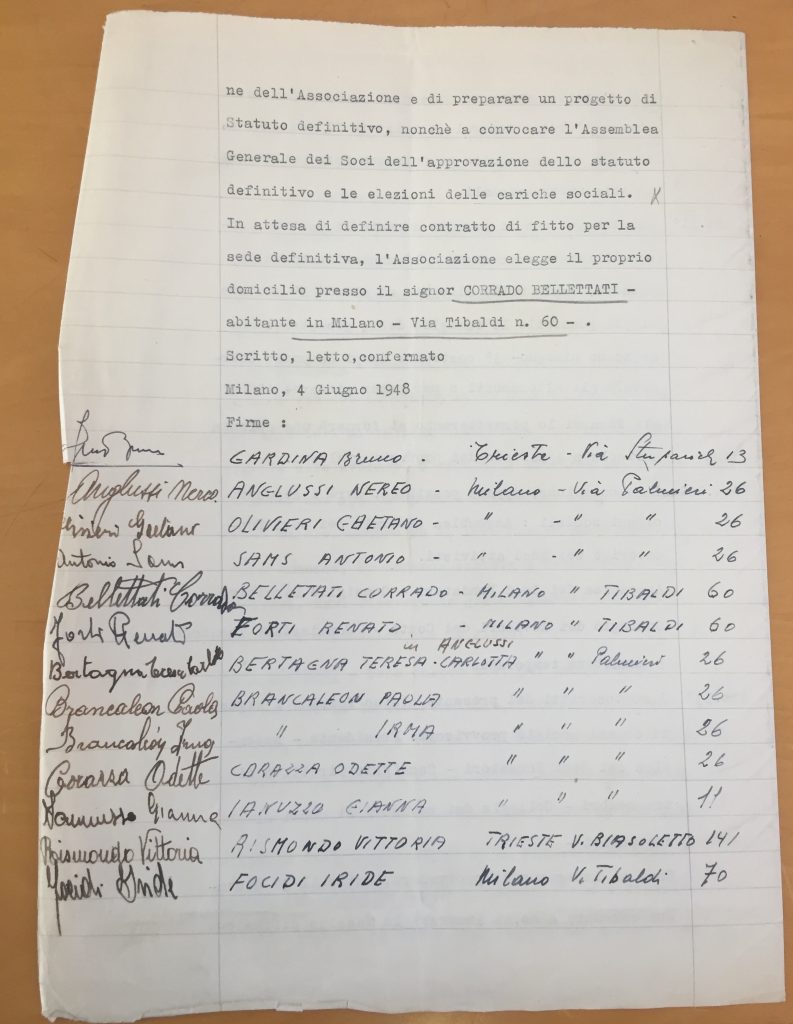

The 4st page of ACF Temporary Charter.

After further articles regarding the internal governing bodies, the Charter ends with the signatures of all the founding members, and their addresses, which allow for further discoveries. The first signatory is … Bruno Gardina! The 36 years-old man was living in Trieste. Then came the signature of another Pola refugee, 27 years-old Nereo Anglussi, who some years later would emigrate to Australia with his wife Carlotta Bertagna Anglussi. The third signature is that of Gaetano Olivieri, soon to became Gardina’s partner in the 1949 Bolzano match fraud: he would later tell the Italian police that his only goal was to entertain his wife Vittoria, one of Bolzano players. The fourth signatory is 24-years old Antonio Sams, a refugee from Lussinpiccolo (today Mali Lošinj, in Croatia).

The fifth signatory, ACF President Corrado Bellettati, seems to have been the figurehead. In mid-June the Questura started to investigate him, soon discovering that this 42-years old carpenter wasn’t an Adriatic refugee, but in fact from Viconovo, a small village near Ferrara. Some months before Belletati had moved to the home of his common-law wife Mrs Giovanna Simoni. This old woman (born in 1888 near Ferrara and immigrated to Milan in 1918), was an employee of the Prada fabric store in Vicolo Santa Maria Valle, she was not only a founding member, but also the ACF Secretary.

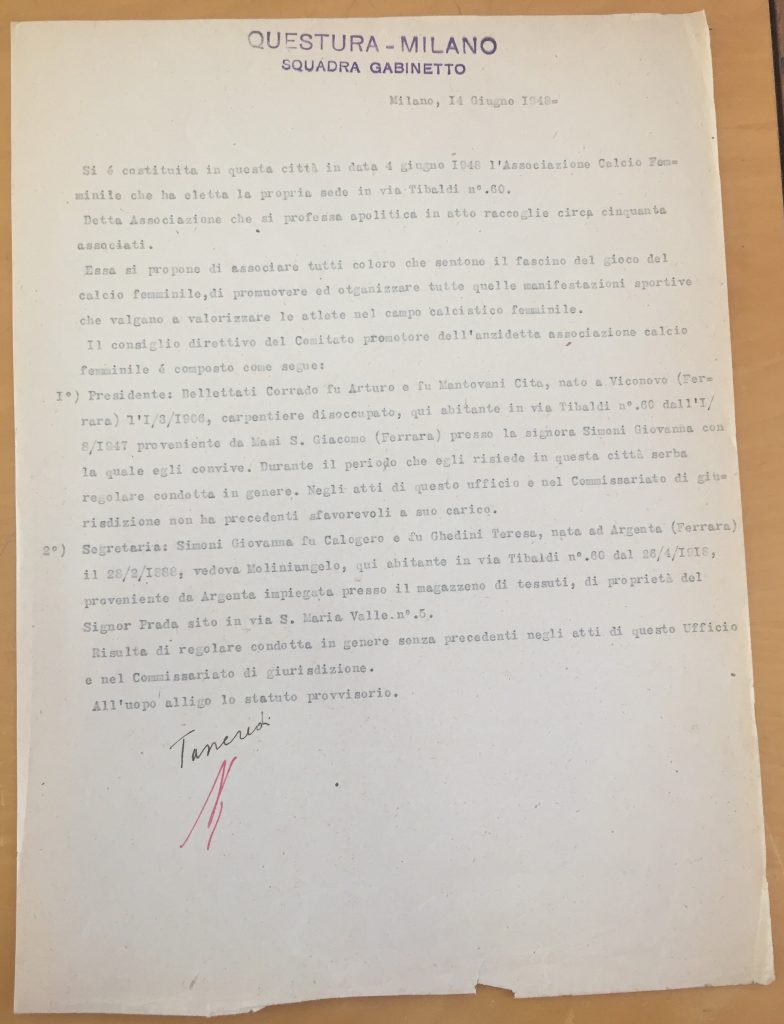

The Questura enquiry about Bellettati and Simoni (14/06/1948).

In July 1948 Bellettati was questioned by Chief Commissioner Adone: he stated that he was the President of ACF, which didn’t exist. He’s described as a man lacking in any political opinion.

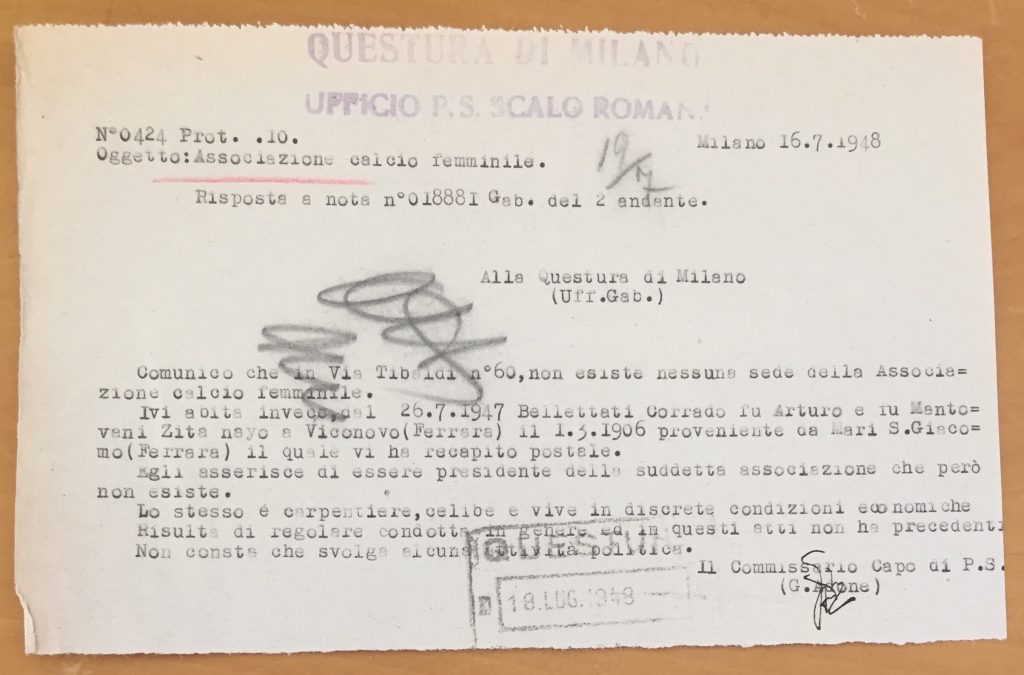

The Questura interrogation of Bellettati (16/07/1948).

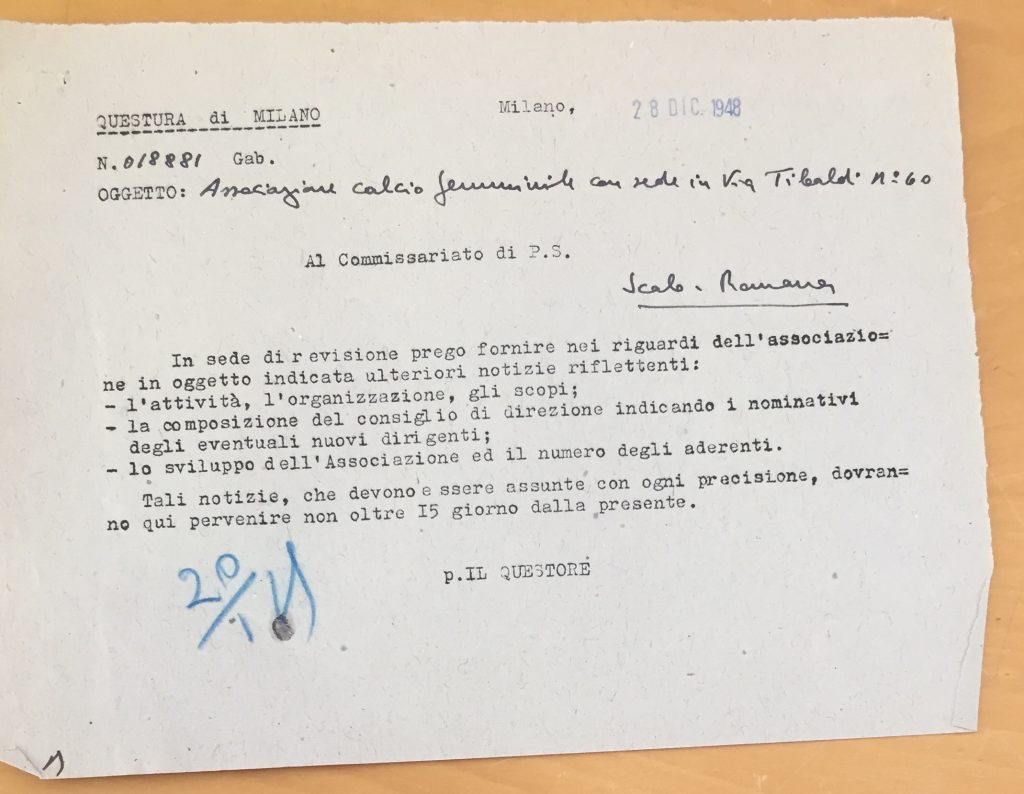

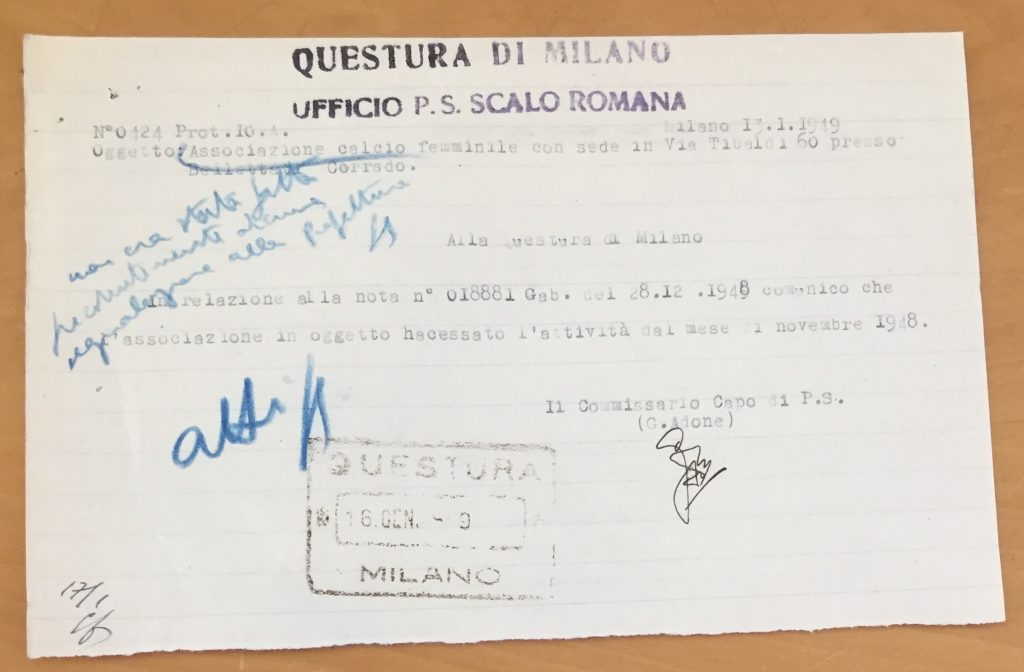

In the closing days of 1948, the Milan Questore required an updated inquiry regarding AFC; two weeks later, Adone replied that ACF had ceased to be in November 1948.

The Questore’s request (28/12/1948),

Adone’s reply (13/01/1949)

Let’s return to the last page of ACF Temporary Charter, to investigate the female signatories, which came after the six male ones. Following Carlotta (Nereo Anglussi’s wife) we find the signature of 20-years old Odette Corazza, who lived (like many of these men and women) in via Palmieri 26. This was the address of a Milanese school, where some Adriatic refugees were placed. This place was unsuitable, due to the fact that a lot of refugees were crammed into a confined space, it proved the perfect scenario for the outbreak of many fights. In March 1950 the Milanese newspaper Corriere della Sera wrote that a furious quarrel began between the young clerk Odette and the 50-years old Anna Baccialini, who were both living in the same room in this via Palmieri refugee camp: the latter accused the first of exploiting the promiscuity of their situation by having a relationship with her husband. A further chapter of the war in the poor that one year previously had taken place in Bolzano.

Female refuges in the Catania camp (mid-1950s’)

Source: http://intranet.istoreto.it/esodo/parola.asp?id_parola=19

Young girls in Servigliano camp

Source: Archivio private Assunta Muzzarini, http://intranet.istoreto.it/esodo/parola.asp?id_parola=19

There were sports activities among the refugees of the camps: a football men’s team in the Mantua camp (1950)

Source: Archivio Privato Maria Manzin e Mario Maracich, http://intranet.istoreto.it/esodo/parola.asp?id_parola=19

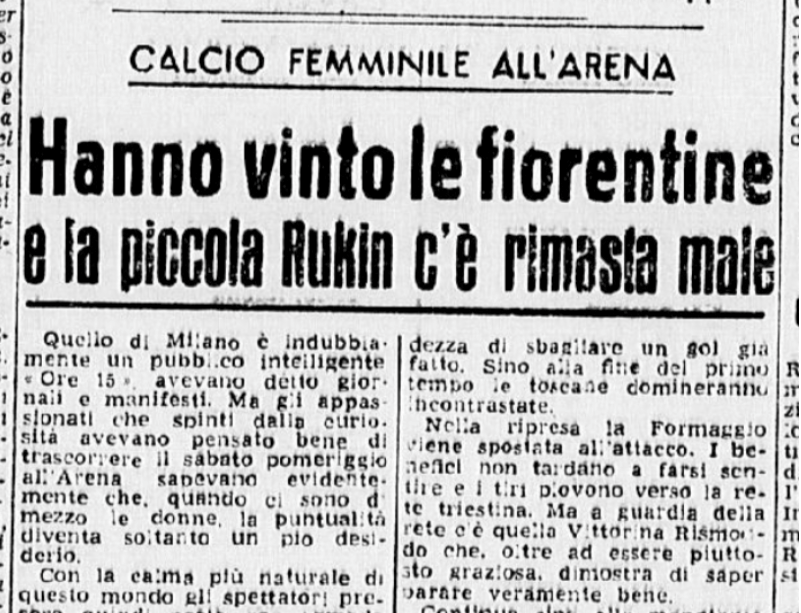

On 6 March 1948, a women’s football match was played at the Arena Civica, the teams were from Venezia Giulia (the Trieste region) and one from Tuscany. Thanks to an article published by La Gazzetta dello Sport, we know that the goalkeeper of the first team (who wore yellow shirts) was Vittorina Rismondo, “who is not only quite beautiful: she’s also a good goalkeeper”. This player can be matched with the twelfth ACF signatory Vittoria Rismondo, who actually lived in Trieste. In the same “Rappresentativa Giuliana” team there was a defender called “Bertagna”, this was Teresa Carlotta Bertagna, Anglussi’s wife.

The article about Rappresentativa Toscana – Rappresentativa Giuliana 2-0, played on Milan on 6 March 1948

Source: La Gazzetta dello Sport, 7 marzo 1948, p. 2.

Since we don’t know the names of the 1949 calciatrici, we don’t know if the female signatory of 1948 ACF Temporary Charter (Teresa Carlotta Bertagna Anglussi, Paola and Irma Brancaleon, Odette Corazza, Gianna Ianuzzo, Vittoria Rismondo, Iride Focidi) actually played in Bolzano, although is quite likely. These 7 female 1948 founding members, such as the 22 1949 players, seem to be mere pawns in a man’s game: their names and signings are at the bottom of the list, none of them had an active role in ACF (such a difference with 1933 GFC players!). One year later, in Bolzano, these players will be exploited by Gardina, arrested and issued with expulsion papers. Women’s football was attempting a rebirth in Italy, but found that it had to fight hard against the increased prejudices and obstacles of a ‘hypocritical’ democratic Italy.

Article © of Marco Giani

For more details about the Sports History funds at the Milan Archivio di Stato, and the transcription of all sources quoted in this article, see:

https://www.academia.edu/43667097/Fonti_per_la_storia_dello_sport_nellArchivio_di_Stato_di_Milano

For some sources about Italian women’s football from 1946 to 1959, see:

https://sorelleboccalini.wordpress.com/le-fonti_calcio-femminile-italiano-1946-1959/

For an Italian article about the 1949 Bolzano match, see: