Parts 1 and 2 of this series – see the following links

Part 1 – https://goo.gl/Fx38w5

Part 2 – https://goo.gl/pxkonF

-

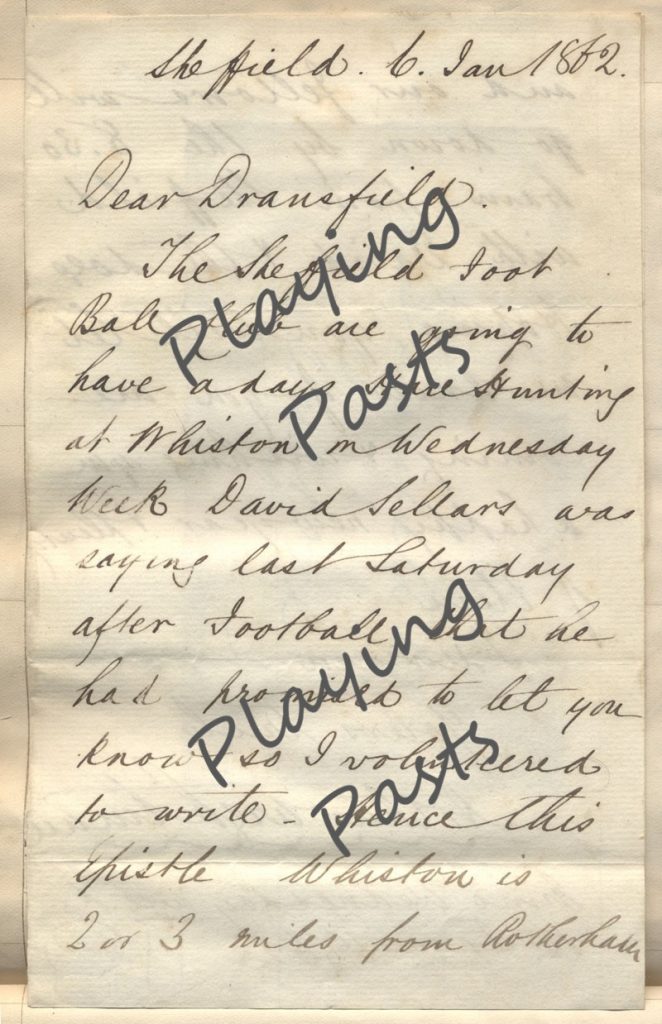

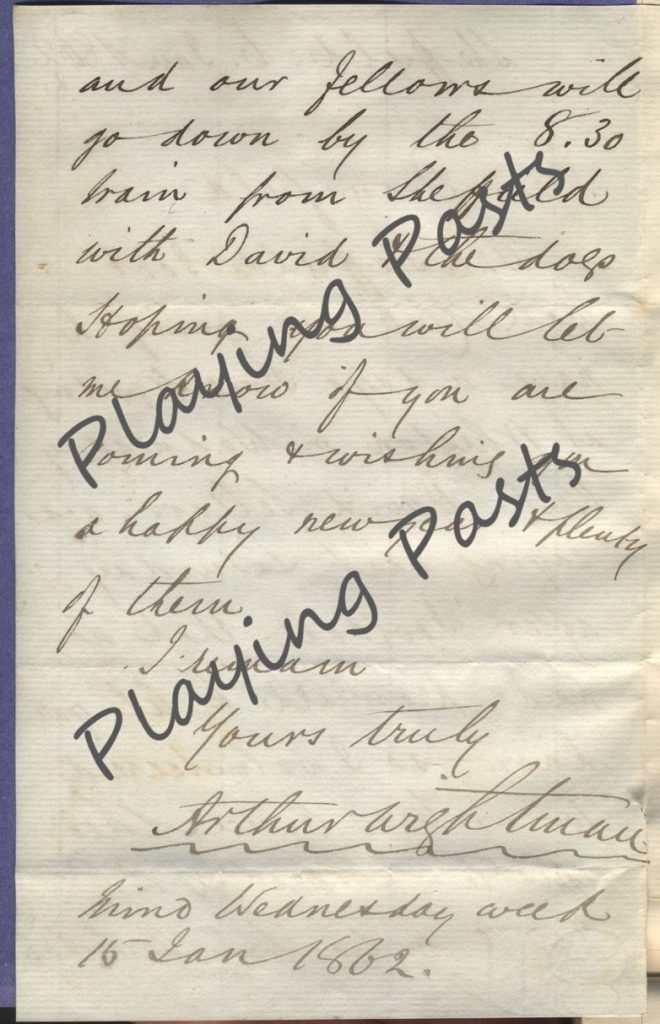

A letter to Dransfield written by Arthur Wightman who would play in the first representational match together with John Charles Shaw, Sheffield v London in 1866. It is interesting to note that the Half Crown subscription fee, included beer and tobacco for the year, most probably at the Adelphi Hotel. Socialising was clearly a part of membership of the Sheffield club. This letter is further proof.

Discovered by the author during the course of research

John Charles and Mary Ann may well have lived above the business in Norfolk Row initially. However, their first son George, is shown in the 1861 census as having been born in the Banner Cross area of Sheffield in 1855. Their second son, John Stanley, was born in 1858 in Sheffield. This census also shows the family living in the Nether Green area of Upper Hallam. John Charles is recorded as widower, because in 1859 Mary Ann had died, after just six years of marriage. The Sheffield Independent of 13th August reports her death:

‘On the 5th inst., at Springwood terrace, Heeley, after a lingering illness, Mary Ann, wife of J. C. Shaw, Law stationer and daughter of Mr H. W. Garnett, surgeon dentist aged 24’

The servant in the house, at this time, is Thurza Moorhouse, the aunt of John Marsh. She was, no doubt, someone who was known and who could be more than trusted in looking after the household. The loss of his wife must have been a devastating blow, compounded by the fact that he was left fending for two very young children aged four and not quite two. A still very young John Charles would have looked for somewhere a little nearer to home for his football. Who the driving force was behind the notion of a Foot Ball Club at Hallam in 1860 between Captain Thomas Vickers and John Charles Shaw is an unknown. Power struggles between Vickers and Creswick are a possibility.

Vickers, living at Tapton Hall, had the financial clout and the need to draw men to the Volunteer cause. What is known is that John Charles Shaw becomes the Secretary and Captain of the newly formed club. What better arrangement for a man who loves his football than to play only a few minutes away from his young family in Upper Hallam. In July 1861, John Charles Shaw married Annie Waterfall, the 21 year old daughter of James Waterfall, a Sheffield file manager/manufacturer. The Waterfall family, prior to the marriage, had been living on Ranmoor Cliffe Road, within walking distance of Hallam Foot Ball Club. In 1862, Annie gave birth to their first child, Jane. Whether the two boys, from the first marriage lived with them is unknown. Certainly by 1871, John Stanley was living with his uncle and grandfather in Wortley. He died shortly after, aged 15. What becomes of Bernard is unknown.

The 1871 census shows the new family living in Watery Lane Ranmoor, with John Charles as a Law Stationer aged 38. This is the first of many occasions when he becomes untruthful about his age. The census shows a growing family with the addition of another Bernard, John Charles and Alice Maud. Interestingly, Bernard was given the middle name of Lefevre. There was a Leeds based family of Shaw and a Charles Shaw born in 1759, the son of the Reverend Shaw, Rector of Womersley near Doncaster. He married Helena Lefevre and assumed the additional surname by Royal Licence in 1789. They had two sons. Charles Shaw-Lefevre became 1st Viscount Eversley, Speaker of the House of Commons and John Shaw-Lefevre who served under Lord Grey. Both of them went to Trinity College, Cambridge and became prominent Liberal politicians. Both were well known in the 1860s. John Charles could have traced his lineage to this side of the family and then utilised the connection, to advance his position in Sheffield. Either way, the 1860s was a very good decade for developing his career.

The Sheffield flood was a case in point. Shortly after the flood in March 1864, John Charles Shaw was appointed by John Newbould, the solicitor to the flood commissioners, to head a team of thirty clerks dealing with flood claims. Whether this was the same John Newbould who, along with brother, Samuel Newbould were members of Sheffield Foot Ball Club is not clear. However, it was the same John Newbould who had offices at 12 Norfolk Row. It is also clear that John Charles Shaw’s ability to lead and, more importantly, organise was emerging. This experience may have helped shape his political allegiance to the Conservative Party. Certainly, he would have been part of the Dransfield Penistone solicitor’s connection with local Conservative politics, when working as a Clerk in their offices. He would have come across the local landowners, such as the Wharncliffe’s of Wortley Hall, Spencer Stanhope’s of Cawthorne and the Milnes family of Fryston Hall, who owned land in Thurlstone. John Dransfield Senior acted on behalf of these landowners. He was a Returning Officer for the Penistone district and both he, along with John Ness, were agents for the Conservative candidates too. The Sheffield flood caused untold human suffering through loss of life and destruction of property, but success in compensation claims varied. It appeared that those on the Electoral Roll were well looked after, whilst others were almost treated with contempt. The final snub came in July 1864, when the Liberal Government sided with the water company by placing a twenty five percent increase on water charges, to cover the cost of the compensation. This must have had a deep impact on local politics. Not too long after, a by-election occurred, causing John Charles Shaw to assist the Conservative candidate, but the Liberals were elected by a narrow margin. John Charles Shaw was to commit the rest of his life to promoting the Conservative cause as a political agent.

-

Above is a letter to the Dransfield office written by John Charles Shaw. This shows him as a political Registration Agent in 1875.

Discovered by author during course of research

In November 1865, Henry Joseph Garnett, brother of his first wife, proposed John Charles Shaw for initiation into the Britannia Lodge of Freemasons in Sheffield. His ballot in December 1865 was successful and he was initiated on the 11th January 1866. The Worshipful Master who initiated him was Henry Joseph Garnett, who would also ‘Pass and Raise’ him to the sublime degree of a Master Mason by March that year. John Charles also joined the Lodge Chapter, The Royal Arch Chapter of Paradise. Thus followed a forty year association with freemasonry in Sheffield, and, later in Birmingham, for John Charles, and a long association with the Earl of Wharncliffe, who himself had joined the Britannia Lodge in 1861. Wharncliffe may have encouraged John Charles to join. It would have given him a greater social network and schooled him in the art of conducting business meetings.

According to John Steele, 1866 saw John Charles invited to become the Secretary of the Midland Union of Conservative Associations based in Birmingham. This date is surely incorrect, as his time as political agent was in very early stages and, as yet, he had not organised the great demonstrations held at Nostell Priory, which catapulted him into the political limelight. His time as political agent was taking shape. 1866 was also the year that saw the first representative soccer match between London and Sheffield and John Charles Shaw was selected to play in this first encounter. 1867 saw the Youdan Cup competition take place, with twelve Sheffield clubs taking part in this, the world’s first knock-out tournament, which was eventually won by Hallam. The Sheffield Football Association was formed shortly after the Youdan Cup.

The clubs that participated in this competition were the founding members. They were desirous of a set of rules to determine play, as well as a keen interest in setting up an injured player’s insurance fund, the very first of its kind. Harry Walker Chambers was elected President and John Charles was on the players committee. By 1868, he was elected Vice-President with John Marsh on the Committee of members, and in 1869, President. He was to hold this office for the next fourteen years. What is highly significant is that John Charles Shaw is a major contributor in almost all of the initial stages of football development in Sheffield. He is connected not only with the establishment of the Sheffield Football Club, Hallam Club, and Youdan Cup, but also the founding of the Sheffield Football Association with its Players Insurance Fund, and the historic links with London and Birmingham.

-

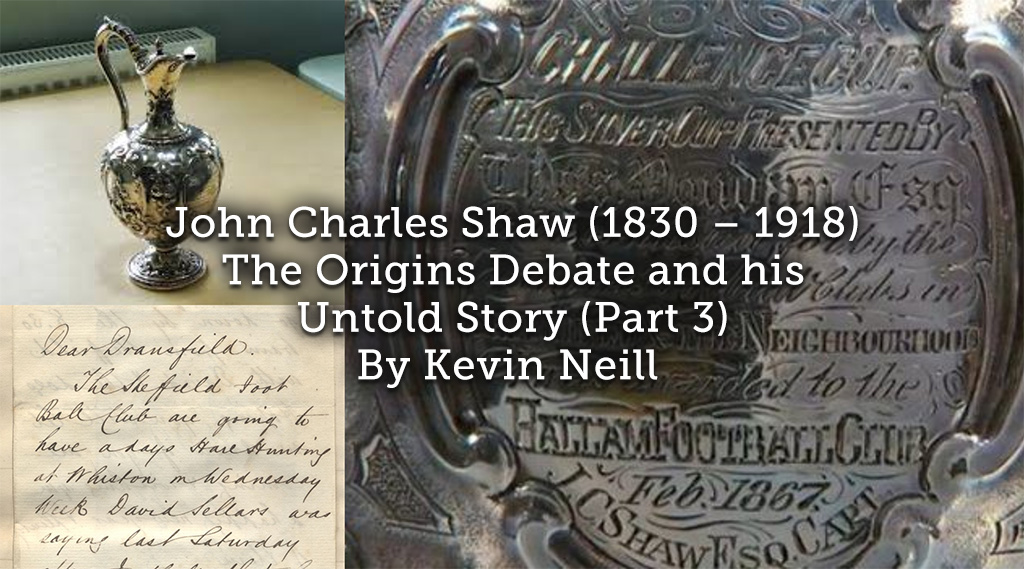

The Youdan Trophy. The world’s first knock-out challenge cup competition. Won by the Hallam Club and held aloft in triumph by the captain, John Charles Shaw. The following year saw the Cromwell Cup, the world’s second oldest competition. Won by the Wednesday Club and held aloft in triumph, by the victorious captain John Marsh, both captains, former pupils of Penistone Grammar School.

Source: by permission of Hallam Football Club.

John Charles Shaw’s association with freemasonry undoubtedly provided him with contacts regarding his political affiliations. Interestingly, it may have had an influence on the two year waiting rule for Sheffield clubs, which said that newly formed clubs could not become full members of the association until a two year probationary period had passed. In May 1867, the Britannia Lodge passed a resolution to exclude members who were twelve months in arrears with their subscriptions after a written warning had been given. This was to ensure that the lodge accounts were kept in order. One of the priorities of the fledgling association was good accounting. The two year waiting rule before membership was clearly to ensure that clubs could be self-financing and viable. This led to the establishment of the Cromwell Cup for ‘waiting’ teams that fell into this category, which was played under the Sheffield association rules. The cup was first won by The Wednesday Club under the captaincy of John Marsh. After two years, these clubs could become members of the association, but would have to pay subscriptions backdated. At the 1870 AGM, a proposal was submitted, seconded by John Marsh, that the association had the power to deduct monies due to clubs, if in arrears. This proposal was carried.

In 1871 the Dronfield club was struck from membership ‘for the breach of an important pecuniary rule’. It could have been that lodge financial lessons had been applied. Certainly by 1881, four out of the six officers of the association were members of Sheffield lodges and the Earl of Wharncliffe was Honorary President. A point of interest here, also, is the absence of the Sheffield Club competing against other Sheffield teams for many years. Westby points out that this was due to the Sheffield club taking their game to other areas, almost in missionary fashion. John Charles, in the 1870 AGM, states that Sheffield refused to play the town clubs because the opposition consisted of the same players time and time again. A more realistic reason was that this refusal started after the infamous clash of players in the game against Hallam in 1862. Creswick of Sheffield, exchanging blows with Waterfall of Hallam, which was reported in the local press. A man of Creswick’s position, as a military leader in the town, where he had a reputation to maintain, could not be undermined by mere fighting on the field of play. Better to go out of town, which of course is what the Sheffield club did.

Article © Kevin Neill

For part 4 – bit.ly/2WXDYUe