Playing Past is delighted to be publishing on Open Access – Sporting Lives, [ISBN 978-1-905476-62-6] a collection of papers on the lives of men and women connected with the sporting world. This edited volume has its origins in a Sporting Lives symposium hosted by Manchester Metropolitan University’s Institute for Performance Research in December 2010.

Please cite this article as:

Peake, Robin. Patrick O’Connell, an Irishman Abroad, In Day, D. (ed), Sporting Lives (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2010), 55-72.

5

______________________________________________________________

Patrick O’Connell, an Irishman Abroad

Robin Peake

______________________________________________________________

Fabio Capello, Louis Van Gaal, Johan Cruyff, Leo Beenhakker and Terry Venables. Thus reads an illustrious list of names; some of the men who have won the Spanish La Liga Championship as a coach. Irishman Patrick O’Connell, who led Betis Balompie to the title in 1935, has earned his place amongst this select group. His feat has not been repeated at the Andalucian club, making his triumph all the more notable, and his place in the club’s folklore all the more secure. O’Connell had played as a half-back in the English and Scottish first divisions in the years enveloping the First World War, before coaching in Spain’s premier league competition. He captained Manchester United and was given the same honour to lead his country in their historic victory over England in February 1914, as Ireland won their first ever Home International Championship. As a coach he won twelve major and minor trophies in Spain, including winning the regional Lliga Mediterrania with FC Barcelona when football was disrupted by the Civil War.

Figure 1. Patrick O’Connell in Hull City gear

Source: Sports Express (Hull), January 10, 1914

Though a handful of white-haired men can recant his achievements in some of Andalucia’s bars, sporting stardom has begot O’Connell no legacy either in his homeland or in England, where he spent most of his playing career.[1] There is no statue or plaque commemorating his achievements, and few football fans, even those who keenly follow the clubs he played for, have ever heard of him. Today he is little more than a footnote in the game’s history, a statistical anomaly featuring in the appendix pages of the histories of the clubs he played for, and even then, sometimes misnamed.[2] Yet were he to have played in today’s intensely media saturated milieu, he would be a regular feature on the front pages as well as the back. As a young man, O’Connell married the woman he got pregnant, and would later leave his wife and four children. When he bigamously married in Spain, neither of his wives apparently ever knew of his deceit.[3] However, whilst he deserves no accolades as a father or husband, his successful coaching career abroad deserves attention. An Irish coach with a British pedigree, O’Connell’s success in Spain was measured both by the trophies that he won, and the extent to which he adapted and stayed in the country in comparison with both his peers and the stay-at-home British coaches of today.

Patrick Joseph O’Connell was born in Dublin on 8 March 1887 to Patrick and Elizabeth, one of nine children and the eldest son.[4] He grew up in the Drumcondra area in the north of the city, and by 1899 the family was living in a four roomed house in Jones Terrace, a street whose predominantly Roman Catholic populace reflected the religious identity of the city.[5] Patrick O’Connell senior was a clerk at Boland’s Corn Mill; junior was said to have worked there as well, though the 1901 census lists him as a glassfitter, at age fourteen.[6] His social class was fairly typical for a would-be footballer. On Jones Terrace, there was a family of bricklayers, a plumber, a few carpenters and an unemployed sanitary officer; the street consisting mainly of members of the skilled and semi-skilled classes three and four.[7] O’Connell’s early years ran in tandem with the development of association football in Ireland. The Irish Football Association was formed in Belfast in 1880, some seventeen years after their English counterparts. By the time O’Connell was born, football was being played in an organised setting in Dublin and a priority of the IFA was to encourage the growth of the game outside of Belfast and Ulster.[8] In 1892 the Leinster FA was established in Dublin to promote the game in the province. The LFA grew from a membership of 11 clubs in 1899, to 65 just two years later.[9] This extraordinary growth can in part be attributed to the dissolution of the Army FA, but was also probably a response to the creation of a number of pitches for the association code across Dublin, and the location of the Ireland v England match of 1900 at Lansdowne Road.[10] This decision was part of the IFA’s ‘missionary work’ which aimed to encourage the growth of the sport in the south, despite international matches in Dublin taking a financial loss.[11] Thus by the time O’Connell entered his teenage years, football was becoming an increasingly attractive leisure pursuit in Dublin. Furthermore, he lived just fifteen minutes’ walk from the pitches at Fairview Park where he could play the sport, and though as a youngster he lived in three different houses, O’Connell and his family were never more than 100 metres from the Jones Road playing fields, now Croke Park and home to the Gaelic Athletic Association. Bohemians had played matches there, as did Tritonville AFC in the early 1900s.[12] By the time the GAA had purchased the playing fields in 1908, ninety soccer clubs were registered with the Leinster FA.[13] Patrick O’Connell played for two of them.

His first known team was Frankfort, a small club who played in the minor cup competitions and who were probably located in Phoenix Park.[14] He then played for Strandville, a club who were formed around the turn of the century and who played just a twenty minute walk from his home. With them, O’Connell won the Leinster Junior Cup in May 1908.[15] There was double cause for celebration when he married Ellen Treston that same month though it was probably forced upon him; she was three months pregnant with his child.[16] By September, he had moved north to senior side Belfast Celtic, with Strandville acting as a ‘feeder’ club for them at that time. At Belfast Celtic he was a regular starter as a centre-forward but by the end of the 1908-9 season, he was spotted by the manager of Sheffield Wednesday and was signed and converted to a half back, as English and Scottish teams stepped up their pursuit of Irish players.[17] Though he travelled with the club as part of their 14 man playing staff on their first continental tour, to Scandinavia in 1911, O’Connell was largely a fringe player who made only fleeting appearances when others were injured.[18] After only twenty-one appearances in just over three seasons at Wednesday, he dropped down a league to Second Division Hull City in May 1912 for a transfer fee of £350.[19] At Hull he was a first team regular, known as a ‘sound and judicious’ player who was ‘as amusing on the field as he is off’ by the local press who knew him affectionately as ‘Patsy’.[20] When Davy Gordon was unable to lead the side, it was O’Connell who was appointed temporary captain and showed ‘splendid leadership’.[21] His consistent and capable play during the 1913-14 season, attracted the attention of the Irish selectors as it had done two years previous. On Valentine’s Day 1914 he captained Ireland to a memorable 3-0 triumph at Middlesbrough, only their second victory over England in more than thirty attempts, their first on the opposition’s patch. A month later, O’Connell picked up his fifth cap as part of the team which drew against Scotland where he finished the game despite picking up a serious elbow injury.[22] The game finished a goal apiece, meaning that Ireland won the Home International Championships for the first time in over three decades of trying.

Perhaps it was his international fame, coupled with his league form that led to him signing for Manchester United in May 1914. Undoubtedly there were other reasons. According to the Sports Express, O’Connell had requested a transfer having desired to leave Hull for some time, with Liverpool, Chelsea and Newcastle United all interested.[23] However closer examination reveals more, exemplifying what Bale terms ‘layers of truth’, a model outlined by Denzin, which argues that something new always becomes visible in biographical work.[24] It transpired that O’Connell had felt in a sufficiently strong position to ask the club for a new three year contract and permission to live twenty miles away in Hornsea owing to Ellen’s now ‘delicate state of health’, a version initially stifled by club sources.[25] Whilst they were losing one of their best players, the club would also benefit from a transfer. Hull City were struggling to remain solvent as a result of their high wage bill. They were paying half what Manchester United were on wages despite attendances being around a fifth and were predicted to be upwards of £2,000 in debt at the beginning of the 1914-15 season owing to summer wages and an absence of gate money.[26] Furthermore, on Easter Monday 1914 Hull’s Anlaby Road ground was seriously damaged by a fire. To carry out the repairs the club took a loan of £1,000 from a local businessman.[27] Within two weeks of the fire, O’Connell was bought by Manchester United for the same amount, and became their second most expensive signing, £400 paid up front and two cheques of £300 to follow.[28]

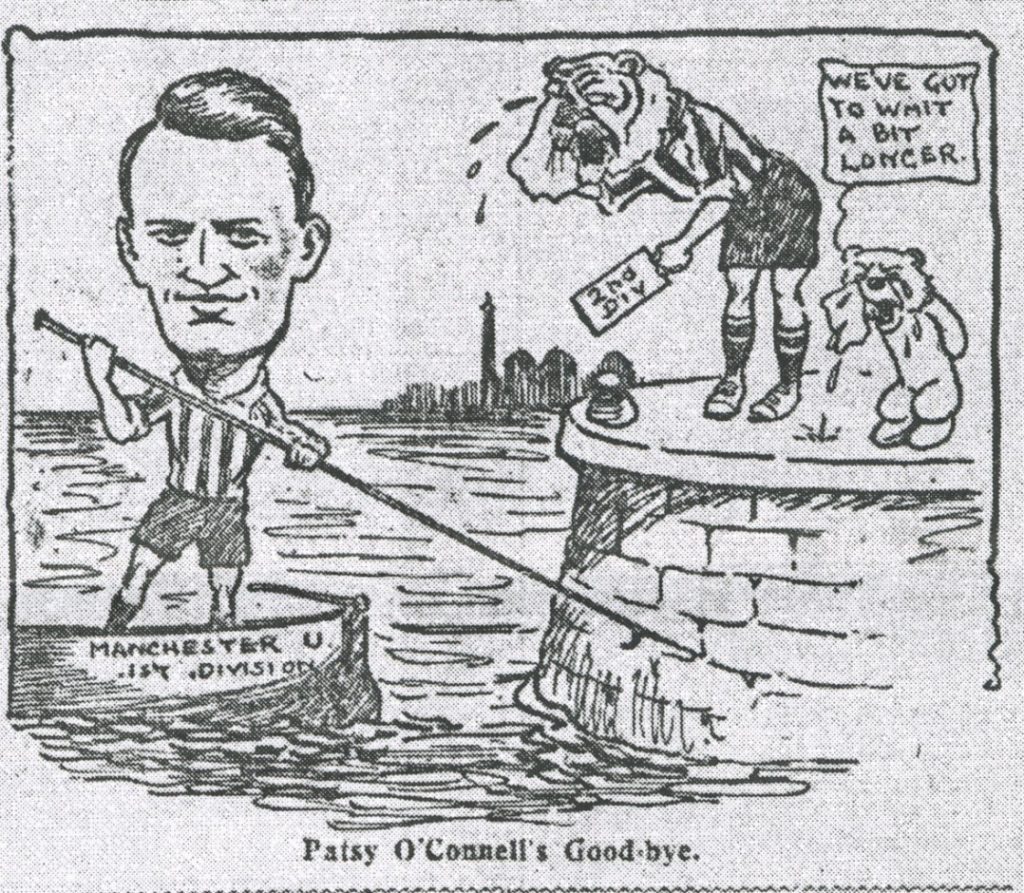

Figure 2. Moving from Hull to Manchester United

Source: Sports Express (Hull), May 16, 1914

It was at Old Trafford that he reached the pinnacle of his playing career, playing regularly for a leading club. The press recognised him as the club’s best half-back, ‘brainy and skilful’, ‘industrious and clever’, though accusations of poor ball distribution continued to be levelled against him, as had been noted during his days with Belfast Celtic.[29] In early 1915 he was described by Athletic News as ‘a much more finished and restrained player than he was years ago with Sheffield Wednesday. Then he was merely a wild Irishman, but experience has made him a calculating man.’[30] Yet the hot temperament alluded to here must still have followed him, his anger being characterised by one cartoonist and it was noted that during one match he caused a referee to limp when he ‘accidentally’ kicked him on the ankle.[31] O’Connell was the sixth Irishman to play for Manchester United, the first from outside Ulster, and in January 1915 he became the first Irishman to captain the club.[32]

Figure 3. O’Connell’s anger was noted by at least one cartoonist

Source: Manchester Football Chronicle, Sept. 18, 1915

By this time the war which was supposed to be over by Christmas was intensifying and many of O’Connell’s peers and teammates had signed up. A Footballers’ Battalion had even been created, and forty of the staff at Clapton Orient registered from the off.[33] Eight of Manchester United’s 1914-15 team would sign up; Sandy Turnbull would later be killed at Arras.[34] In reality though, the experiences of Burnley centre half Tommy Boyle, who admitted to trying to avoid military service, were probably more representative.[35] The Footballers’ Battalion only attracted around 7% of the League’s professionals.[36] It was much more common to find footballers engaged in alternative employment, heeding the call of future Football League chairman Charles Sutcliffe, who said that those illegible or unable for active service were ‘to seek and engage in employment of military service and significance’.[37] Patrick O’Connell, along with teammates Enoch West, George Anderson, and a handful of others from Manchester United, found war supplies work at the Ford Motor Works in Trafford Park where O’Connell became a foreman.[38]

Clubs found the first wartime season a difficult period to operate in financially with contractual obligations to fulfill despite a considerable fall in gate receipts. Manchester United had to delay the installments of O’Connell’s transfer fee for a full twelve months.[39] On 29 March 1915, the expected announcement was made that owing to the ongoing war effort, there would be no summer wages for three months, and that upon the resumption of payments, the basic maximum wage would drop from £4 to £3 per week.[40] Shortly after this news which limited their earnings, the footballers of Manchester United and Liverpool were brought into serious disrepute, as it was alleged and later proven that some of them had been involved in squaring a match between the two teams, and placing money on the correct score. The match in question was at Old Trafford on 2 April 1915, Manchester United winning by two goals to nil. It was a result that many punters had betted upon, and one which particularly helped United in their battle against relegation. Patrick O’Connell, captain of the home side, curiously missed a penalty in the second half when the score was 1-0.[41] His shot was so extravagantly wide, that it is reported the referee consulted his linesman, convinced that something was amiss.[42] The fix insufficiently subtle, the sporting press and the authorities demanded to know who was involved. The commission set up to investigate the match, involving both the FA and the Football League, issued their findings at Christmas. It found five of those who played, including just one of the United team, Enoch West, guilty of pre-arranging the result for the purpose of betting and winning money thereby and permanently suspended them from taking any part in football.[43] As Athletic News commented, ‘It is beyond the power of human credibility to assume that only one of the [United] players was “in the know”’.[44] O’Connell had been interviewed by the Commission, but was not deemed guilty. As captain, he was probably never thought of as being entirely innocent either.

Under relaxed registration rules, O’Connell spent the last wartime years playing as a guest for Rochdale Town and Clapton Orient when it became clear that he was surplus to requirements at Manchester United.[45] In August 1919 Scottish side Dumbarton signed him for £200.[46] O’Connell was by now, growing estranged from his wife, Ellen, and their four children. It seems that they followed him to Scotland for a while, only to return to Manchester.[47] After a fairly uneventful year in Dumbarton, he returned to England. Responding to an advert offering ‘good wages to experienced men’, he signed for Ashington in May 1920 and moved to the North Eastern League side without his family.[48] A year later, he was appointed as player-manager of the club, now elected to the newly formed Third Division North.[49] He helped the club to tenth place in the league, but with a four figure loss sustained, the better and higher paid players at the club had become a luxury.[50] At the end of the 1921-2 season he was offered for sale.[51] However, with no bids forthcoming, he was released on a free transfer by the club in June and embarked upon a coaching career in Spain which would span three decades and four different systems of governance.

Academics have drawn various conclusions as to the occupations that many early professional footballers took up upon retiring from playing, though solid evidence regarding the spectrum of employment of former sportsmen has been hard to locate, even for contemporary sociological studies.[52] The consensus, drawn from a range of sources and much of it impressionistic, is that footballers at the lower end returned to their previous trades, while many of the footballers who made it to the top of their profession ventured into a new trade as publicans and owners of small businesses, or advanced in their current trade, working with football clubs as managers, trainers or scouts.[53] This is neatly captured by the legendary Manchester United half-back line of Duckworth, Roberts and Bell. Charlie Roberts, who had been O’Connell’s predecessor at United, ran a successful tobacconist’s business, even creating a cigarette brand called ‘Ducrobel’ named after the famous trio.[54] Of the other two, Bell became a football trainer and Duckworth a publican.[55]

An attempt to offer something more like quantitative data can be made by collecting some information from a popular source. From January to May 1930, Topical Times ran a series entitled ‘Cup Heroes of other days and what has happened to them’. Presenting information on a player-by-player basis, it details the post-playing exploits of those footballers who appeared in FA Cup finals from 1898 to 1914, covering most of the winning sides and a few of the losing finalists.[56] However, the series neither mentions every job each player held after his career, nor gives much of an indication as to how long they were engaged in their various jobs. It must also be remembered that given the range of teams selected, any chronicling of these details can only be said to be representative of the game’s elite.

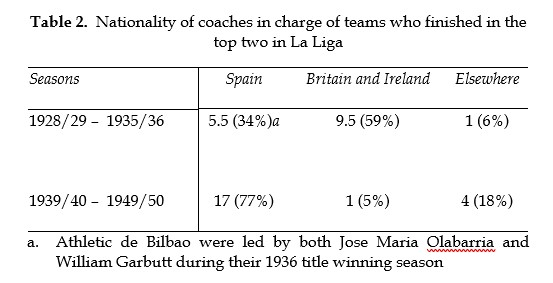

The Topical Times Cup Heroes series provides information regarding the post-playing employment circumstances of 155 unique players. As shown in Table 1, some 5% of players took manual jobs in factories; the same number worked in the mines.

A considerable number were self-employed. 41% of our sample of players operated their own business. Of these, some ran shops as butchers, grocers, confectioners and tobacconists. Ten managed their own hotels but the largest grouping of those who ran their own business were publicans who made up 19% of the total sample. That almost one in five players was in the licensed trade adds substance to the stereotype of the ex-footballer as a pub landlord. Yet we need to remember that this is a sample of FA Cup finalists, players who were more likely than their less successful counterparts to have both the money to establish a business, and the fame to attract the punters. One would expect that a sample taken from less successful teams would produce more manual workers and fewer publicans. Nevertheless, it is clear that a large number of footballers at the top of the ladder ran their own business after hanging up their boots, and many of these were licensees.

A sizeable number too remained in football. The series mentions turnstile operators, groundsmen, directors and scouts. Many more were employed in a more hands on role, as managers, trainers and coaches, the latter term likely to denote the role now commonly referred to as manager.

Table 1. Post-playing occupations of FA Cup finalists, 1898-1914

Source: Topical Times, January 18 to May 19, 1930[57]

Topical Times lists 15 men as trainers, and 35 as football managers or coaches, a combined unique sample of 46, just one short of the number of all the publicans, hoteliers and colliers combined. Although it is recognised that – even amongst the elite – only a small number of footballers remained in the game in a variation of the coaching role, that 30% do is a significant number. And whilst our data is far from infallible, it is clear that Patrick O’Connell’s post-playing role as a coach was not a surprising choice of career. It is even less surprising when one considers that O’Connell had been the on field captain at Ashington, as he had been at Manchester United and intermittently at Hull. Fishwick has commented that a ‘player with a reputation for maturity, reliability, good judgment and leadership might attract directors as potential management material’.[58] Selectors evidently thought O’Connell fitted these criteria when they chose him as captain for club and country, as did the press who variously called him a him a ‘commanding figure’ and ‘something of a leader’.[59] As well as the leadership qualities which others had pinpointed, his industrial management experience would also have made him a choice candidate for managerial posts. Carter has argued that the development of the football manager was in line with similar developments throughout industry. He contends that the earliest football managers held duties not too dissimilar to those who managed in factories and industrial sites.[60] O’Connell’s experience as a foreman at the Ford Motor Works in Trafford Park further strengthened his candidacy.

Of the 46 men from our sample who went into coaching or management, 12 of these took their trade abroad. Popular destinations were Canada, Holland and Germany. Others like Alf Spouncer and Vincent Hayes went to Spain.[61] Thus when Patrick O’Connell – an Irishman, but through his pedigree effectively a British coach – went to Real Racing Club de Santander in the summer of 1922, he was not the first to make the journey. Jack Greenwell was in charge of FC Barcelona since before the war ended, as was Arthur Johnson at Madrid and William Barnes at Athletic Club de Bilbao. Another Englishman, Fred Pentland, who had been interned during the First World War while coaching in Germany and then coached the French National side in the 1920 Olympics, was in charge of Santander for the two seasons previous to O’Connell. Many were hired because of their background in British football which had a reputation par excellence on the continent. Steve Bloomer probably benefitted from networks with former teammates Pentland and Ted Garry who were coaching in the north of Spain when he was hired as coach at Real Irun.[62] Others got jobs through more official networks like the FA or the employment bureau of the Association of Football Players’ and Trainers’ Union.[63] Still others replied to adverts posted in the British sporting press. In May 1922, O’Connell replied to an advert in Athletic News on behalf of a Spanish club who were seeking a ‘first class trainer coach’.[64] Applicants were invited to reply to R. B. Alaway, a former amateur with Middlesex Wanderers who had built up a number of contacts in Spain through organising footballing tours there.[65] The advert only appeared for one week, when most stayed for at least a fortnight, and three weeks later there was a notice from the Spanish club thanking all those who had applied, stating that there were too many applicants to reply individually.[66] Managerial posts were keenly sought after, whether at home – 58 had applied for the Preston job in 1925 – or abroad with many footballers, like other entertainers and sportspeople, keen to remain in a trade which they knew well.[67]

In Spain, the 1920s was the decade when football’s popularity took off. Introduced at the end of the nineteenth century by British sailors and engineers, the springboard from which the sport launched itself into the wider public’s enthusiasm was the national team’s surprise success at the 1920 Olympics, when they won the silver medal.[68] Many clubs, such as Santander, Betis and Irun enjoyed royal patronage, indicated by the prefix Real. Between 1920 and 1930, attendance at football matches quadrupled in some areas.[69] In 1926, professionalism was legalised, and two years later a national league had been established.[70] As if to illustrate the great strides the game had made during this decade, in May 1929 forty thousand Spaniards watched their national team defeat England by four goals to three, humbling the country which, in the words of one journalist, ‘exported the goods, [but] lost the knack of making them.’[71]

O’Connell’s reign at Santander lasted until 1929, where he was relatively successful, leading the club to seven successive wins in the local Federación Cántabra, though never achieving much success in the cup. It was during these years that he met and bigamously married Ellen O’Callaghan, a red headed Irish girl.[72] Whilst his separation from his first wife had increased his range of mobility, his marriage in Spain, albeit not to a native, increased the likelihood of him settling permanently.[73] Other notable coaches from Britain who were successful in Europe were Pentland and Jimmy Hogan, who were said to be fluent in Spanish and German respectively.[74] Some did not settle just so well. Athletic Bilbao’s first foreign coach, a Mr Shepherd, returned home after only a few months in 1910, and Steve Bloomer noted the difficulties of being apart from his wife who remained in England.[75] By 1932, O’Connell moved to the city of Seville, via a stint at Oviedo, to take over as coach of Betis Balompie, their royal prefix removed under the rule of the Second Republic. It is at Betis where he is most fondly remembered. In 1935 he guided the club to their sole La Liga championship. Only promoted to Spain’s premier division four years previously, it was a fantastic footballing achievement, one recognised by the municipality who gifted the club a new stadium.[76] At Betis, O’Connell had twice guided his side to victories over FC Barcelona in the cup. This, coupled with his recent success at Betis, made him an ideal candidate for the vacant post at Barcelona. In the summer of 1935, Patrick O’Connell became the coach of arguably Spain’s biggest club, at a time when the country was on the cusp of civil war.

Figure 4. El Entrenedor: O’Connell at Barça c. 1936 (FC Barcelona)

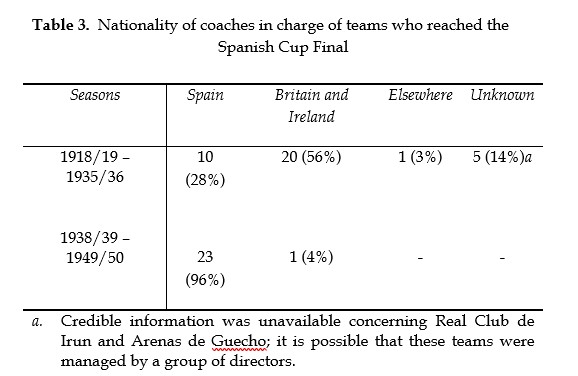

At Barcelona, Patrick O’Connell won the Campeonato de Cataluña in his first season, securing a bonus of 1,000 pesetas to add to his 1,500 pesetas monthly wage.[77] After guiding the club to 5th in the league that same season, he led them to the final of the Spanish Cup, in June 1936. There his team met Real Madrid, the first time these two great rivals had met on Spain’s greatest stage. Madrid won by two goals to one, an ominous victory for the club who would become known as Franco’s team against a Catalan side who would consistently oppose the regime. A month later, with the team on holiday and O’Connell back in Ireland, General Franco and his men took control of the Canary Islands and Spain lurched into civil war. As a club, Barcelona suffered heavily during the conflict; its stadium was bombed and its President was shot dead by Falangist troops loyal to Franco.[78] Under threat financially and politically repressed, they were presented with a lifeline in April 1937. Mexican businessman Manuel Mas Soriano got in contact with the club and offered them 15,000 US dollars plus expenses to embark upon a footballing tour of Mexico. The club agreed readily and a six match tour over two months was arranged, commencing in June.[79] O’Connell oversaw the trip, which saw a two month long tour extend into four and twelve of the sixteen players enter exile in Mexico and France.[80] O’Connell returned with the reduced party of players and staff but by the closing stages of the conflict, he had left the country along with the rest of the coaches from the British Isles, staying with his brother Larry in London.[81] Whilst the conflict and reduced wages that accompanied the Civil War drove out O’Connell, Pentland, and their peers, the reality was that coaches with a British pedigree had lost the aura which had accompanied them in the early part of the 1920s. While touring teams once seemed invincible, now even the national team could be defeated. Though five different Englishmen had won the Spanish Cup in the 1920s, by the early 1930s, the British coach was becoming increasingly expendable as coaches from Hungary, Germany and Austria grew in stature. Jimmy Hogan claimed in 1933 that English coaches were no longer in demand in Europe, with the exception of the Netherlands.[82] In Spain, Hungarians such as Lippo Hertza and Franz Platko, South Americans like Enrique Fernandez Viola and a plethora of national talent steadily replaced coaches from England, Scotland and Ireland. Over twenty British coaches have been identified as working there in the 1920s, but as Tables 2 and 3 show, the top clubs were no longer looking abroad for guidance.

Following Franco’s victory, O’Connell was corresponding with Barcelona who were evidently expecting him to return.[83] However he declined to return to the club, and instead went back to coach Betis once more. In doing so he became the only coach from the British Isles to return to Spain after the conflict, perhaps aided by a nationality and religion not deemed threatening to the Regime. In 1942 he made the short journey to CF Seville where he led the club to the runners up spot in La Liga, at that time their joint highest ever position. Eventually his coaching career petered out, coaching Betis and Santander once more before carrying out some scouting work for teams in the south of Spain. That even during these years he didn’t take his second Irish wife back to their homeland or to England shows just how settled he was in his adopted country; that he continued to find work, defied the decline of the British-educated coach abroad.

Table 2. Nationality of coaches in charge of teams who finished in the top two in La Liga

Sources: Official Club Websites, Correspondence with clubs.

In the 1950s, he was tracked down by Daniel Treston, his son from his first marriage, who had abandoned the O’Connell name in favour of his mother’s maiden name. O’Connell had adopted a ‘Ne’er the twain shall meet’ stance and neither of his two families knew the other existed. He cannily introduced Daniel as his nephew, further embittering his son, who was open about his hostility towards his father.[84] This charade over, he remained in Seville, save for when he went to London to be with his brother in his final days. Patrick O’Connell died on 27 February 1959, in St. Pancras, aged seventy-one.[85]

The direction of Patrick O’Connell’s career upon ending his playing days was not altogether unusual. His experience in leading men both on the field and in the factory, combined with his pedigree in British football eased his path into coaching. That he coached abroad was certainly uncommon but not altogether rare, and his initial move to the north of Spain was in keeping with British coaches who took up positions there. However, O’Connell does stand out from the other coaches in Spain due to his staying power. No other British coach had a career which straddled both sides of the Civil War. That Patrick O’Connell achieved not just success, but longevity in his coaching career in Spain, marks him out among both his peers, and the modern British manager.

References

[1] See Richard Holt, ‘The legend of Jackie Milburn and the life of Godfrey Brown’, in Writing lives in sport: Biographies, life-histories and methods, ed. John Bale, Mette Christensen, and Gertrud Pfister (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2004).

[2] Padraig Coyle, Paradise lost and found: The story of Belfast Celtic, (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1999), 25.

[3] Sue O’Connell, in discussion with the author, St. Helen’s, 27 Nov. 2009.

[4] 1901 Irish Census.

[5] Thom’s Dublin Street Directory, 1899; 1901 Irish Census.

[6] 1901 Irish Census.

[7] 1901 Irish Census; See W.A. Armstrong, ‘The use of information about occupation: I. As a basis for social stratification’, in Nineteenth Century Society, ed. E.A. Wrigley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972), 191-214.

[8] Tony Reid, Bohemians A.F.C. official club history 1890-1976 (Dublin: Tara, 1976), 9.

[9] Irish Football Association minutes of Committee 1898-1902, minutes for 1899 and 1901 AGMs.

[10] Irish Football Association minutes of Committee 1898-1902, minutes for 1899, 1900 and 1901 AGMs; Neal Garnham, Association football and society in pre partition Ireland (Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 2004), 12.

[11] Irish Football Association minutes of Committee 1898-1902, minutes for 1900 AGM; Irish Football Association minutes of Committee 1903-9, entry for 9 May 1908.

[12] Reid, Bohemians A.F.C., 11-13; Irish Football Association minutes of Committee 1903-9, entry for 5 June 1906.

[13] Irish Football Association minutes of Committee 1903-9, minutes for 1908 AGM.

[14] Sport, September 5, 1908.

[15] Ibid. May 9, 1908.

[16] Sue O’Connell, in discussion with the author, St. Helen’s, November 27, 2009.

[17] Football League registration book for Division 2, 1908-9; Irish News, March 29, 1909; See Robin Peake, ‘Irish sporting migration c.1890-1925’ (paper presented at the annual meeting of the Irish History Students’ Association, Trinity College Dublin, 20 Feb. 2010).

[18] Richard Sparling, The romance of the Wednesday, 1867-1926 (1926; Wiltshire: Desert Island Books, 1997), 201.

[19] Football League transfer list, 1912-13; The Week and Sports Special, 11 May 1912.

[20] Sports Express, January 31, 1914; September 20, 1913.

[21] Ibid. October 25, 1913.

[22] Irish News, March 16, 1914; Eastern Morning News, March 18, 1914.

[23] Sports Express, April 4, 1914.

[24] John Bale, ‘The mysterious Professor Jokl’ in Writing lives in sport, ed. Bale, Christensen, and Pfister, 31-4.

[25] Sports Express, May 2, 1914.

[26] Ibid. May 31, 1913; March 21, 1914; April 11, 1914; December 21, 1915; Steven Tischler, Footballers and businessmen: The origins of professional soccer in England (New York: Holes and Meier, 1981), 84.

[27] Mike Peterson, Century of City: The centenary of Hull City AFC, 1904-2004 (Harefield: Yore, 2005), 19.

[28] Manchester United minutes of Board of Directors 1912-22, entry for April 22, 1915.

[29] Athletic News, January 4, 1915; January 18, 1915; January 25, 1915; March 29, 1915.

[30] Ibid. January 4, 1915.

[31] Manchester Football Chronicle, September 18, 1915; February 13, 1915.

[32] Manchester United minutes of Board of Directors 1912-22, entry for January 14, 1915.

[33] Steve Jenkins, ‘Clapton Orient’s brothers in arms’, Soccer History, 3 (2002), 10.

[34] Athletic News, December 27, 1915; Topical Times, March 8, 1930.

[35] Topical Times, April 26, 1930.

[36] Derek Birley, Playing the game: Sport and British society, 1910-1945 (Manchester: Manchester University Press 1995), 73.

[37] Athletic News, April 26, 1915.

[38] Manchester Football Chronicle, April 17, 1915; Simon Inglis, Soccer in the dock (London: Willow Books, 1985), 47.

[39] Manchester United minutes of Board of Directors 1912-22, entries for May 22, 1914; January 14, 1915, November 9. 1915.

[40] Football League minutes of Management Committee 1913-19, entry for March 29, 1915.

[41] Liverpool Daily Post, April 2, 1915; Manchester Daily Dispatch, April 3, 1915.

[42] Graham Sharpe, Free the Manchester United one (London: Robson Books, 2003), 51, 90.

[43] Minutes of FA council 1914-20, minutes of the proceedings from July 13 1915 to December 31, 1915.

[44] Athletic News, December 27, 1915.

[45] Sporting Chronicle, December 30, 1916; Manchester United minutes of Board of Directors 1912-22, entry for August 24, 1917.

[46] Manchester United minutes of Board of Directors 1912-22, entry for August 19, 1919.

[47] Daniel Treston, interviewed by Raidió Teilifís Éireann (undated) re-broadcast on ‘Bowman on Sunday’, July 18, 2010; Sue O’Connell, in discussion with the author, St. Helen’s, November 27, 2009.

[48] Athletic News, April 19, 1920; April 26, 1920; May 3, 1920; Football League transfer list, 1922-3.

[49] Blyth News, May 19, 1921.

[50] Garth Dykes, Ashington AFC in the Football League (Nottingham: SoccerData, 2011) 45-6.

[51] Football League transfer list, 1922-3.

[52] Peter Hill and Benjamin Lowe, ‘The inevitable metathesis of the retiring athlete’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 9 (1974): 5-32.

[53] Dave Russell, Football and the English (Preston: Carnegie, 1997), 49-50; Nicholas Fishwick, English football and society, 1910-1950 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989), 82; Tischler, Footballers and businessmen, 99-100.

[54] Tony Matthews and John Russell, The complete encyclopedia of Manchester United Football Club (West Midlands: Britespot, 2002), 276.

[55] Topical Times, March 8, 1930.

[56] It covers the FA Cup winning teams of 1898, 1901, 1903 to 1912 and 1914, as well as the losing finalists of 1903, 1904 and 1912. I am grateful to Matthew Taylor, whose work pointed me to this valuable source.

[57] The sample also included 29 other occupations, ranging from a clergyman to a strongman, but they are too numerous to tabulate here.

[58] Fishwick, English football and society, 82.

[59] Athletic News, February 22, 1915; Dumbarton Herald and County Advertiser, December 24, 1919.

[60] Neil Carter, The football manager: A history (Oxford: Routledge, 2006), 48.

[61] Topical Times, April 12, 1930; David Hunt, The history of Preston North End Football Club (Preston: PNE Publications, 2000), 123.

[62] Peter Seddon, Steve Bloomer: The story of football’s first superstar (Derby: Breedon, 1999), 162; Matthew Taylor, ‘Football’s engineers? British coaches, migration and intercultural transfer c.1910-c.1950s’, Sport in History, 30 (2010): 149.

[63] Taylor, ‘Football’s engineers?, 146-7.

[64] Athletic News, May 22, 1922.

[65] R.B. Alaway, Football all around the world (London: Newservice, 1948).

[66] Athletic News, June 12, 1922.

[67] Preston North End minutes of Directors meetings 1921-6, entry for May 5 1925; Joan Jeffri, ‘After the ball is over: Career transition for dancers around the world’, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 11 (2005): 346.

[68] D. Shaw, ‘The political instrumentalization of professional football in Francoist Spain, 1939-1975’ (PhD diss., University of London, 1988), 14; Andrew McFarland, ‘Ricardo Zamora: The first Spanish football idol’, Soccer & Society, 7 (2006): 1-13.

[69] John Walton, ‘Reconstructing Crowds: The rise of association football as a spectator sport in San Sebastian, 1915-32’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 15 (1998): 48.

[70] Liz Crolley and David Hand, Football and European identity (London: Routledge, 2006): 98.

[71] Ivan Sharpe, Forty years in football (London: Sportsman Book Club, 1954), 125.

[72] Sue O’Connell, email message to author, August 10, 2010.

[73] Jacob Mincer, ‘Family migration decisions’, Journal of Political Economy, 86 (1978): 753; Pierre Lanfranchi and Matthew Taylor, Moving with the ball (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 53; Stephen Castles and Mark Miller, The age of migration, 4th ed. (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009), 33.

[74] Seddon, Steve Bloomer, 167; Sharpe, Forty years in football, 49.

[75] Phil Ball, Morbo: The story of Spanish football, 2nd ed. (Guildford: WSC, 2003), 68; Seddon, Steve Bloomer, 163.

[76] Ball, Morbo, 153.

[77] FC Barcelona minutes of Board of Directors and Workers Committee, entries for November 7, 1935, May 22, 1939.

[78] Jaume Sobreques i Callico, Historia del F.C. Barcelona: De la crisi al gran creixement, 1931-1957, Vol. II (Barcelona: Editorial Labor, 1993), 24-5.

[79] Ibid., 23.

[80] New York Times, September 21, 1937; Jimmy Burns, Barça: A people’s passion, 2nd ed. (London: Bloomsbury, 2000), 120.

[81] FC Barcelona minutes of Board of Directors and Workers Committee, entry for May 22, 1939.

[82] Topical Times, March 18, 1933.

[83] FC Barcelona minutes of Board of Directors and Workers Committee, entry for May 22 1939.

[84] Daniel Treston, interviewed by Raidió Teilifís Éireann (undated) re-broadcast on ‘Bowman on Sunday’, July 18, 2010.

[85] Register of deaths for England and Wales, January to March 1959.