PART ONE

Do we need to rethink the split in English rugby in 1895?

There has been a temptation to romanticise the formation of the Northern Union in 1895 (forerunner of what became known as the Rugby League in 1922) as a sporting revolution in the interest of the working class. By that time the game of rugby – known in West Yorkshire colloquially as ‘football’ – had been transformed from a sport based on the supply of enthusiastic participants (that is, players) to an entertainment business based on the demand of spectators.

My research of what happened in Bradford in the years leading up to the formation of the breakaway league give weight to the argument that the split is better described as having been an industry restructuring. In my opinion the motivation of the founder clubs was first and foremost to optimise their profitability rather than the welfare of players. Lingering affections for rugby union in Bradford at the beginning of the twentieth century might also suggest that things were more complex than the generally accepted version of history. Specifically, I challenge the official claim of the Rugby Football League that ‘The breakaway was caused by the northern clubs’ desire to pay players which was outlawed at the time in Rugby Union’.

Further findings of how football evolved in Bradford challenge a number of other ‘long-established truths’ about rugby history. This leads me to believe that further local study is necessary to enhance understanding of the history of sport in Great Britain and, in particular, the reasons for the pivotal split in English rugby in 1895.

A matter of monopoly control

My argument is that the formation of the Northern Union was entirely consistent with previous developments regulating sporting competition in Yorkshire in the nineteenth century, specifically the tendency towards behaviour associated with monopoly competition, or to be precise traits more commonly associated with cartels. The same instinct towards concentration of power was also revealed in the relationship between Bradford FC and Manningham FC. The Park Avenue club actively sought to extinguish the threat of the emergent rival after 1883 in order to preserve its local hegemony. This was the making of a blood feud between the two clubs who essentially became business competitors. In my opinion the overarching theme of nineteenth century rugby in Bradford was about the exercise of monopoly power.

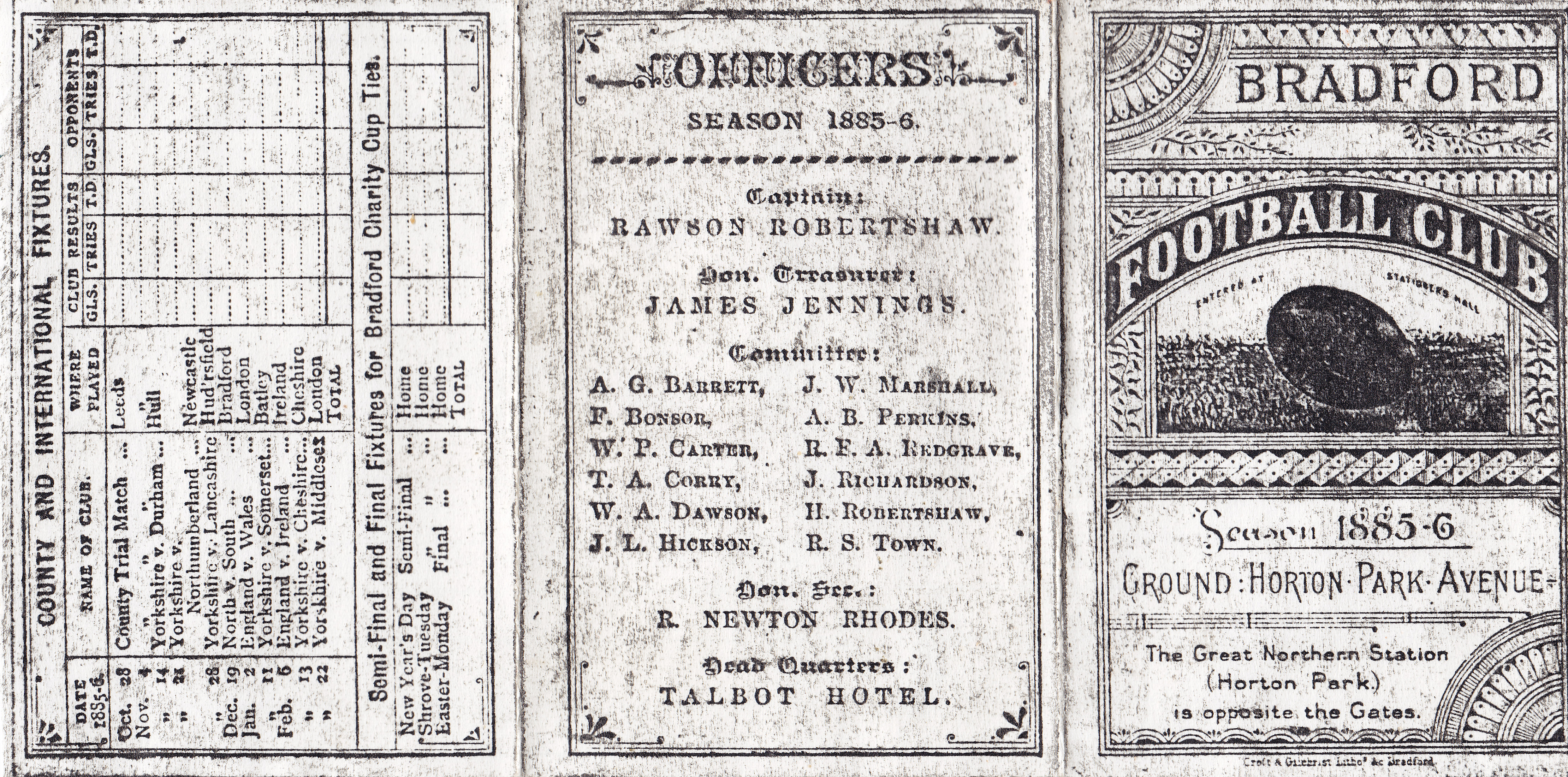

Bradford’s sporting DNA was derived from cricket which set the pattern for sport to become an expression of civic patriotism and loyalty. My research has also revealed a link between the Bradford Cricket Club and the Young England movement in the 1840s that was mirrored in the connection between members of the Primrose League and leadership of Bradford’s senior rugby clubs in the 1890s. As an industrial frontier town in the nineteenth century, sport played an important role in defining a Bradford identity and providing a degree of social unity – themes that appear to have been overlooked in economic and social histories of the town. There were parallels in the way that the leading Yorkshire cricket clubs jockeyed for power and with what happened in Yorkshire rugby. By the 1860s for example, the Bradford Cricket Club had established a reputation of assertiveness in protecting its interests and challenging Sheffield as the dominant player. In the 1870s the Bradford Football Club was no less hesitant in asserting its influence over Yorkshire rugby as a founder member of the Yorkshire County Football Club in 1874. The pentarchy of clubs comprising Bradford, Huddersfield, Hull, Leeds and York was a magic circle that dominated Yorkshire rugby at the expense of smaller clubs who began to lobby for representation and an expansion of the ruling body in the first half of the 1880s. (Of course, when we speak of ‘Yorkshire’ rugby it was essentially about West Yorkshire and the East Riding with Sheffield entirely pre-occupied with Association rules football.)

Following the formation of the Yorkshire Rugby Football Union in 1887 and then the creation of district bodies, Yorkshire rugby politics was dominated by the tension between the senior and junior clubs. A consistent gripe was that in matters of adjudication relating to grievances or disputes, the Yorkshire committee favoured the senior clubs. Indeed the larger organisations were unapologetic in their defence of economic interests, resisted proposals for gate sharing in cup games and ultimately, demanded control over promotion and relegation to the Yorkshire Senior Competition league. The junior clubs were said to be placated by being granted the opportunity to compete in the Yorkshire Challenge Cup (established in 1876).

- Yorkshire Senior Competition Shield

The YSC league was formed in 1892 in response to financial pressures arising principally from a trade depression and the need to protect income. From the outset, there was exclusivity in who was selected for membership and in Bradford, the senior Park Avenue club came close to achieving its objective of excluding Manningham FC. The junior clubs objected to being left out of the league and responded by creating new divisions such that by 1895 Yorkshire rugby had four tiers – the senior competition had 12 members and 38 junior clubs comprised the three subsidiary divisions.

The issue of broken-time payments

The payment of broken-time to those forced to take time off work to play competitive rugby became an emotive topic for the senior Yorkshire clubs. This was because of the demands placed upon players to play an increasing number of games in a season, coinciding with a period of job insecurity. Financial pressures had forced clubs to increase the number of games to optimise gate receipts and this was sustained by league competition. As a headline issue, broken-time payments came to symbolise the divisions between north and south but it was not the only cause of disagreement. Yorkshire clubs for example resented the southern opposition to rule changes and resistance to the staging of alternate RFU annual general meetings in the north. Those divisions had become raw by the time of the Rugby Union’s annual meeting in September, 1893 when proposals for broken-time to be legalised were defeated. On their part, the southern clubs could be forgiven fears about the domination of English rugby by wealthier northern clubs and the ill-winds of capitalism that left them ill-prepared and impotent to compete. The legions of northern working class players were a bogey for the smaller southern clubs for whom rugby was seemingly threatened with transformation at their expense.

Nevertheless, it is wrong to suggest that northern clubs were united in support of the issue of broken-time payments being allowed. This was demonstrated in 1893 by the fact that a sizeable number of Yorkshire clubs opposed the motion for broken-time at the RFU meeting. A representative of one of the junior Bradford clubs, Bowling Old Lane FC is recorded to have expressed his opposition at that meeting. Contemporary newspaper interviews confirm that other junior clubs in the Bradford district feared a free-for-all at their expense if broken-time was introduced. Once more, the issue revealed the tension between the junior clubs and the seniors in Yorkshire (who had the economic power). Notable however is that on the issue of broken-time payments, a club such as Bowling FC – the third ranking side in Bradford whose membership was solidly working class – had the same economic fears as any of its middle class counterparts in the Home Counties. In fact, in Yorkshire those fears were even more acute thanks to the proximity of the big clubs. Arguably a similar degree of paranoia exists nowadays in English soccer among followers of lower division clubs who fear the implications of wealth becoming increasingly concentrated in a smaller number of big sides.

Even within the larger clubs, the issue of broken-time appears to have been a divisive issue and on various occasions it was a cause of jealousy between different player cliques at both Manningham FC and Bradford FC. It is also mistaken to suggest that all players in the north demanded broken-time payments. Aside from a small and declining number who had the private means to play without the need for compensation, a good number of leading players in the two senior Bradford clubs were pub landlords and thus, self-employed.

Article © John Dewhirst

Links to other articles in this series –

Rethinking 1895 – A Bradford Perspective: Part 2 – https://goo.gl/AmUVgs

Rethinking 1895 – A Bradford Perspective: Part 3 – https://goo.gl/6jZZc2

John Dewhirst is author of ROOM AT THE TOP, A History of the Origins of Professional Football in Bradford and the rivalry or Bradford FC and Manningham FC (Bantamspast, 2016) and LIFE AT THE TOP, The rivalry of Manningham FC and Bradford FC and their Conversion from Rugby to Soccer (Bantamspast, 2016). Refer www.johndewhirst.wordpress.com for details.