Football dominates the headlines and continues to command the attention of millions. Inevitably this has encouraged the question of how it all began and the so-called origins debate pre-occupies sports historians who seek to provide the answers. In turn this has led to the recognition that the circumstances of origin differed across the country and that local studies are vital to better explain the evolution of football.

Nevertheless, to explain how like-minded individuals came together to play the game does not answer how it was that people came to watch and continued to do so. I believe that there is another dimension to the origins debate that needs to be addressed to explain how football evolved from a local pastime to become the global industry of today. An equally fundamental question is how the sport evolved from being a recreation dependent upon the supply of players, to that of a business dependent upon the demand of spectators, with decision-making becoming conditioned by monetary considerations. In other words what were the origins of football as a business?

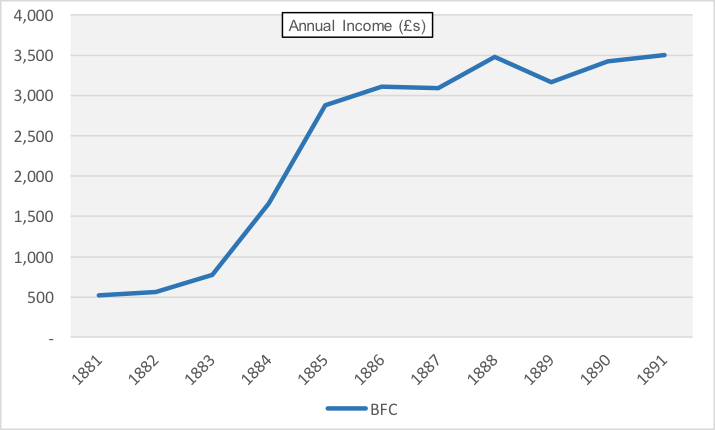

My own interest is the origins of sport – and football in particular – in Bradford in the nineteenth century. (The town’s two senior clubs each switched codes twice, from Rugby Union to the Northern Union and then to association football so I can be forgiven reference to football in the generic sense.) As far as football was concerned, there were no folk / mob football traditions in Bradford whose population growth had been driven by immigrants. The town’s original football club, Bradford FC could trace its origins to 1863 and the coming together of public school alumni. It began as a recreational body and did not begin playing competitive fixtures with other clubs until February, 1867. By the mid-1870s it was recognised as the leading side in Yorkshire and fast forward to 1890 it was acclaimed as one of the wealthiest sports clubs in England.

Bradford was at the heart of the English industrial revolution in the nineteenth century but it was also at the forefront of the commercial transformation of sport. If evidence was needed of how Bradford FC became established as a local institution, you need only consider the growth in the club’s revenue during the first decade of its existence. To have achieved a seven-fold increase in turnover in seven years is impressive for any business and a phenomenon that is deserving of examination. This paper offers the example of what happened in Bradford as the basis of a framework that could be applied to the study of what occurred in other English towns and cities.

Understanding the business behaviour of football clubs provides another (albeit colder) way to explain headline topics as varied as professionalism, attendances and the split in English rugby in 1895 rather than reliance upon softer, sociological interpretations. Specifically, my study of the circumstances in Bradford identifies underlying economic factors having driven the formation of the Northern Union in 1895 and contradicts the prevailing explanation based on social class.

The business environment

Local conditions determined the art of the possible and dictated the environment in which a nascent football business could consolidate itself. The following themes were particularly significant in determining what happened in Bradford but I would expect different degrees of emphasis in other places.

- Urban geography – the hilly terrain of Bradford restricted where clubs could play and their proximity to local communities although ironically the shortage of places may have concentrated talent; railways and urban transport networks made grounds accessible.

- Population – the existence of a young catchment with disposable income and time.

- Receptive sporting culture – the Volunteer movement in Bradford had played an important role in promoting athleticism and familiarity with football. Recreational initiatives had also been endorsed and promoted by Tory politicians.

- Competitors against whom to play – parallel developments in neighbouring towns ensured that rivalries would evolve; the failure of soccer to take hold in West Yorkshire of the 1890s was attributed to the lack of available fixtures.

- Substitute forms of entertainment – the absence of alternatives allowed rugby to claim a monopoly of winter sporting entertainment.

Becoming a business

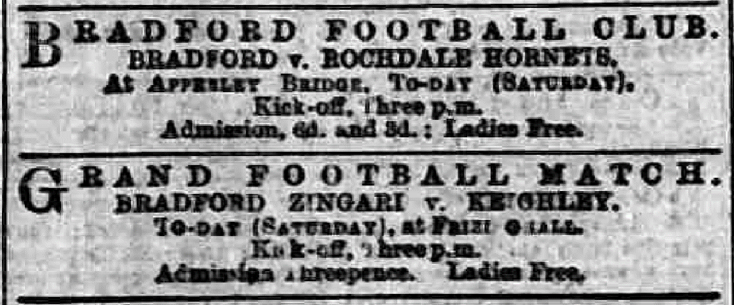

The first stage of the transition of football becoming a business was persuading people to pay to watch, in other words to monetise the activity. This in itself would have been a radical departure in custom and early adverts from the 1870s promoted the game as a form of curio. In West Yorkshire, the introduction of the Yorkshire Challenge Cup in 1877/78 can be identified as the catalyst encouraging public interest and establishing football as a source of entertainment. Crucially however gate-taking was associated with charitable giving and not profit accumulation and from the very beginning, the monetising of Bradford football was linked to raising money for the town’s hospital.

- Bradford Daily Telegraph 10-Jan-1880

If monetising was the initial stage that persuaded people to pay, the second stage could be described as ‘commercialising’ the sport and developing a commercial model capable of generating an operational monetary surplus (or at the least, avoiding a financial deficit). The distinction between monetising and commercialising is subtle and has more to with targeting a financial outcome. Monetising by contrast is about establishing the practice of people tendering money for admission to a game with the proceeds being almost incidental to the game itself.

Commercial activity constitutes a business if it is repeated regularly with the intention of generating a financial surplus from the aggregate of all activity. In other words, a football club would be defined as a business if it deliberately staged repeat commercial activity. The same club might previously have passed through a phase where commercial activity was the exception to the rule and associated with one-off fixtures rather than every game that it played.

Business motives

Prior to the take-off of football in Bradford, cricket had been the dominant sport. Bradford CC had been formed in 1836 and its origins were political as a vehicle to generate popular support for the Tories. The club had historically charged for admission to its games yet although it engaged in commercial activity on an event-by-event basis it is unlikely to have recognised itself as a business. The club’s focus was essentially short-termist and its financial ambitions did not extend beyond paying its rent.

The contrast between Bradford CC and Bradford FC is insightful in terms of considering the motives targeting operational surpluses. A hierarchy of needs can be identified when it came to determination of financial ambitions. Business conduct was not necessarily initiated by professionalism and the paying of players. Payment of a lease liability is an obvious base level motivator but in the case of Bradford FC after 1880 it was the imperative to repay debt that acted as a driver of behaviour. Indeed, a key milestone for the finances of any club was when it expanded beyond a roped-off field to invest in permanent structures that required it to act as a business to pay for them.

The Bradford clubs were all member organisations and no dividends were paid for private reward – operating surpluses over and above the commitment to debt servicing was applied to charitable giving. This link with charity was significant in helping football become fashionable and socially respectable in Bradford, endorsing business-like behaviour. Bradford FC justified its retention of funds to allow ongoing investment in its Park Avenue ground with the promise of deferred benefit to the town’s charities.

Categorisation of football clubs as business is also possible from evaluation of their behaviour to protect operating surpluses. In the case of Bradford FC for example, it is possible to discern capitalist instincts to safeguard its status through application of monopoly power and exploiting its influence within the Yorkshire Rugby Union. It also adopted competitive pricing strategies to optimise revenue and undermine its local rival, Manningham FC. Notwithstanding, allowance needs to be made for the fact that financial management was crude and football clubs did not know their profitability until after the season end. Liquidity dictated decision-making and members were forever mindful of the insolvency implications in a member organisation given their liability to guarantee debts.

Article © John Dewhirst

In the second part of this feature, coming soon, John offers a framework to evaluate the characteristics of football clubs as businesses. Link to Part 2 – https://goo.gl/DVucMx