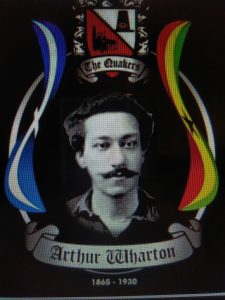

Arthur ‘Kwame’ Wharton is perhaps not a name that is as renowned as it should be in the history of British sport, because despite being a pioneer for black and mixed race players, Arthur’s name has been largely forgotten.

Now however, a National Lottery funded short film, ‘A light That Never Fades’, starring Derek Griffiths is about to be filmed which will focus on the last years of his life when he perhaps began to understand the legacy he would leave behind.

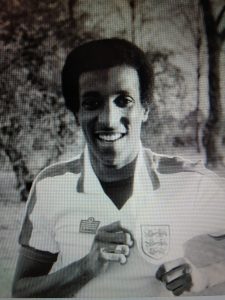

Derek Griffiths, who will play Arthur in the upcoming film

Wharton was born in what is now Accra, on the Atlantic coast of West Africa in 1865 and had a privileged upbringing due to his mother’s family who were descended from Ghanaian royalty and spent four years at Burlington Road School in London in his early teens where he developed his love of sport.

His father was a Methodist missionary of Scottish descent born on the Caribbean Island of Grenada and Arthur was keen to follow in his footsteps so decided to return to England in 1883 to train as a minister at Cleveland College in Darlington.

Soon however, it became apparent that Arthur was an incredibly gifted athlete, and he appeared to excel at every sport he tried, which included cricket, cycling and rugby.

Arthur joined Darlington FC at the very beginning of the club’s history in 1883.

In May 1885 he reputedly turned up at a ‘sports day’ at Darlington Football Club and stunned everyone there by winning the 100 yards.

-

Arthur with The Prince Hassan Cup in 1886

Courtesy of The Arthur Wharton Foundation

-

Arthur in kit during his playing days

Courtesy of the Arthur Wharton Foundation

At this time’ Pedestrianism’, (competitive running ) was a high profile sport and the colour of his skin along with his speed made him very popular with spectators and remarkably in 1886 he became ‘the fastest man in the world’ winning the Amateur Athletic Association’s 100 yards title at Stamford Bridge Stadium in London setting what many consider to be the first 10 second sprint ever recorded which would stand as a world record for over thirty years.

He left college in 1887 but instead of missionary work he decided much to the disappointment of his parents, to become a ‘Professional Pedestrian’, playing for Darlington Town at the same time because Arthur excelled at football and despite his speed played the majority of his career as a goalkeeper.

He signed for Darlington but after twenty games he moved to Preston North End and represented them only in The FA Cup where they reached the semi final in 1888. From 1889 he also played cricket during the summer months and became the first African to play professionally in the Yorkshire league. A year later however he signed as a professional for Rotherham Town, probably because his wife Emma was from the area, becoming the World’s first black professional footballer.

He would spend five years at Rotherham where he was known as ,’The Goalkeeper with The Prodigious Punch’ often turning defence into attack or he would swing from the crossbar and catch the ball between his knees. At 29 he got his chance in the top flight with First Division team Sheffield United, but was unable to displace their regular keeper the 28 stone William ‘Fatty’ Foulke and played just one game for the club.

When Arthur joined Stalybridge Rovers in 1895 he took his first steps into coaching while continuing to play:

They were known as ‘’Wharton’s Brigade’’ because he was very much in charge

says Phil Vasili author of ‘Colouring Over The White Line’ (2000)

He even helped them to sign Herbert Chapman

Chapman would go onto win a combined four league titles with Huddersfield and Arsenal and is often regarded as one of the most influential coaches in the history of the English game.

However, Victorian England wasn’t ready for a black coach and in fact it would take until 1960 for Tony Collins to become the first in the Football League, when he was appointed manager of Rochdale.

Tony Collins, the first black coach in The Football League in 1960.

‘Four Four Two Magazine’ in 1998 highlighted the importance of Vasili’s research, reporting that

Wharton is remembered is all down to journalistic persistence and exhaustive research on the part of Phil Vasili

In fact Vasili’s biography of Arthur ’The First Black Footballer’ first published in 1998 gives a fascinating insight into how the young African made a name for himself in the late 19th century and he strongly believed that Wharton should have gained international honours and commented that,

During his time at Darlington in 1887 there was a strong case for Arthur’s selection for England and based on form, it was a legitimate plea

Unfortunately however it would take until 1978 before Viv Anderson of Nottingham Forest would gain his first cap and become England’s first black football international.

Viv Anderson, England’s first black international in 1978

In 1901 Arthur joined Stockport County as a player but only played six times for the club before retiring in 1902 due to ill health. After retirement, he struggled to adjust and worked at a Yorkshire Colliery as a haulage hand, ran a pub and earned extra money by playing in local football and cricket leagues but felt unable to return to Africa due to the rift with his parents and became estranged from his wife Emma and daughters Minnie and Nora.

Arthur was living in a time when despite his sporting successes, was never fully accepted into British society even though he had volunteered at the outbreak of World War One and had participated in The General Strike in 1926, where he refused to cross the picket lines even though he was desperately in need of the money.

He struggled with alcoholism and sadly died penniless at the’ Springfield Sanitorium’ in Balby near Doncaster in 1930 aged 65 and was buried in an unmarked grave in Edlington cemetery, a forgotten hero.

However in 1997 his grave was given a headstone, after a campaign by ‘Football Unites Racism Divides’, an anti –racism organisation and his family are now able to visit his final resting place and in 2003 Arthur Wharton was inducted into The English Football Hall of Fame.

Arthur’s new headstone in 1997

Courtesy of The Arthur Wharton Foundation

The film, which is likely to be released early in 2024 is the brain- child of the Darlington businessman Shaun Campbell who is the founder of ‘The Arthur Wharton Foundation’ and he has worked tirelessly to ensure that Arthur’s name lives on enlisting the likes of Stevie Wonder, Sepp Blatter, Usain Bolt and Viv Anderson in his campaign to have a permanent tribute erected.

Shaun Campbell, founder of The Arthur Wharton Foundation

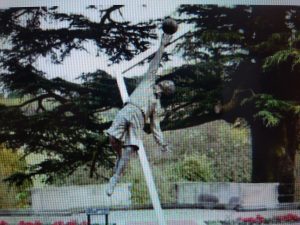

In 2014 the dream was realised when a statue sixteen feet high of Arthur, by the acclaimed sculptor Vivien Mallock was unveiled at St George’s Park in Burton on Trent and now stands at the centre of the St George’s cross at the entrance to The National Football Centre; a fitting tribute to a football pioneer.

The sculpture at St George’s Park

‘A light that Never Fades’ will be aimed at schools and other educational establishments in the North East initially, but Campbell hopes that this is only the beginning, saying

We are working towards bigger projects telling Arthur’s story on film. It could be extremely exciting and this project will help people understand his impact and legacy

This film hopes to shine new light on this remarkable man.

Arthur Wharton 1865-1930

Courtesy of The Arthur Wharton Foundation

Article copyright of Bill Williams