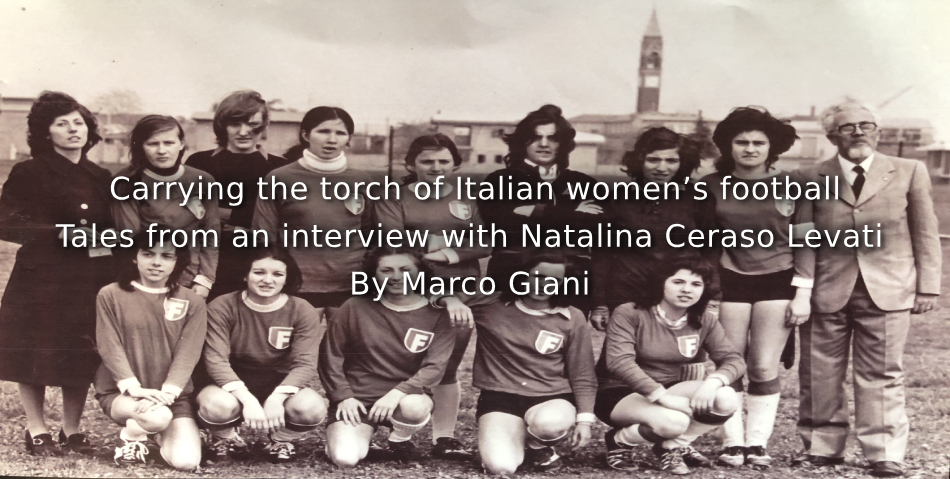

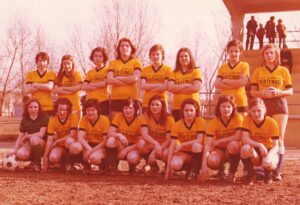

One of the first historical picture of Fiammamonza team

Natalina Ceraso is the first standing, from left; his father Reno is the last, standing.

On 23rd of June, 2022 I had the chance to interview Natalina Ceraso (born in 1944), daughter of Nazzareno “Reno” Ceraso (Gerocarne, 1915 – Monza, 2007) and widow to Fabrizio Levati (Monza, 1945-1995). I spent a whole morning at the Sada Stadium, Monza, talking with the 78-years old lady, who had been a very important person in the history of Italian women’s football. She shared with me not only many tales about the pioneering years of her team (Fiammamonza), but also the whole story of her own family since the founder of the football club was her father Reno. Gaetano Galbiati, Fiammamonza General Manager, was the trusty listener of our meeting, helping Natalina with the digital scans of Fiammamonaza photos, that now can be shared with Playing Pasts’ readers.

- The Sada Stadium, located near the Monza train station

- The Sada Stadium is now home not only to Fiammamonza but also to Sport Club Juvenilia: in 2013 the two football clubs decided to merge.

From a historical point of view, the survival of a women’s football club is a sort of exception. Nowadays, the women’s Serie A is dominated by the women’s teams of the great male football societies such as Juventus, FC Inter, AC Milan, AS Roma …: in the last few years, they had just bought their place in Serie A from the historical women’s clubs such as Cuneo and Brescia. On the contrary, Fiammamonza stands loyal to its history, which began in 1970, as shown by the two murals that each weekend welcomes the fans. I was sure that an interview with Natalina was a big deal, for my historical research about the roots of women’s football in Italy.

- The first mural is dedicated to Fabrizio Levati, the historic trainer («mister») of the team.

- The second is dedicated to the first president, Professor Reno Ceraso, and to the general manager Gaetano Galbiati.

The original club of this women’s football club was Fiamma Ceraso: it was established in 1960 by Reno Ceraso, a PE teacher at Mosè Bianchi, a Surveyors high school located in Monza. Originally, it was focused on female athletics, mini-basketball, and volleyball. The sports society was affiliated with Centro Sportivo Fiamma, the sports federation linked with Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI),see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_Social_Movement, the far-right party founded in December 1946 by some former supporters of Benito Mussolini.

-

An old Fiamma Ceraso pennant ,

both these images taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

- An old Fiamma Ceraso banner, in blue

In the late Sixties Natalina was the sports club secretary. When I asked why she hasn’t been involved as an athlete when she was younger, she told me that, being the first of 5 siblings of a teaching couple, she was babysitting all the time, and she had no time for sports.

When Natalina was a 14-years old high school student, his Italian Literature assigned the class a writing in-class exam a double topic, based on students’ gender. Male students had to write write a short essay about Umberto Saba’s Il Portiere, a poem about a goalkeeper; their female classmates had to write a comment about Virgil’s Aeneid. Yet Natalina decided to write about Saba’s poem: “Why? Because I liked football!”, so much that she used to save pocket money her father gave her for the vending machines to buy sports newspapers such as La Gazzetta dello Sport. Some days later, when the Italian teacher handed back the writing tests, he asked Natalina why she had chosen that topic.

Must I choose the other one?

No, you mustn’t … just tell me why you did so

You know, at home, we’re always talking about sports, I follow many sports, my father is a Juventus fan …

Ok, tell your father that I want to talk with him

One week later, Reno reached the teacher during his lesson in Natalina’s class. The teacher says to Reno (who was an acquaintance of him), smiling:

I would like to inform you about your daughter’s insane passion for football. Do you think it is normal?

In front of Natalina, who was seating in the first line, Reno answered:

I guess she listened a lot about sports, at home … Still, what’s the problem? She didn’t write down a bad essay … I can’t understand why you called me here. As long as she keeps on being civil, why my daughter shouldn’t love football as she does with athletics, volleyball, and basketball?

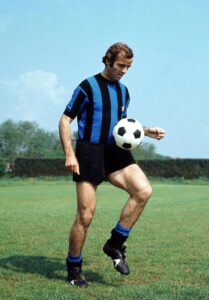

Natalina was a FC Internazionale fan, and her favourite player was Mario Corso.

During her high school and then university years, Natalina was the only girl she knew who was interested in sports: all her schoolmates spent their time just getting a husband. In 1970, the 26-years old Natalina noticed a young lawyer, Fabrizio Levati, walking into the Fiamma Ceraso gym, during basketball practice. Fabrizio asked Reno:

Since all the sports club’s activities are for girls, what about a football team?

Natalina liked football, but her first thought was that a football team was meant to mean more work for her. So she entered the dialogue, saying: «No! Football is just for boys!», and Fabrizio answered:

Shut up! I wasn’t talking to you!». Now Natalina commented: As a sort of revenge for that, I … I married him, later!

In 1972, only 6 months after their first meeting, Natalina and Fabrizio got married.

Fabrizio (first standing) as trainer of Fiammamonza, during the Seventies

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

The first time Fabrizio showed his interest in Natalina was in 1971, when he got two tickets for FC Internazionale – Sampdoria, at San Siro stadium. He walked into the gym during the basketball team training, taking a seat next to her, as none usually dared to do, since she was the President’s daughter. Since Fabrizio was a Sampdoria fan and Natalina an FC Inter one, he proposed to her to attend together the match in Milan. The girl didn’t raise her head, keeping on writing: “What are you talking about? I don’t go out, I can’t go out, no way!”. Fabrizio said just “Stop! Tomorrow I’ll pick you up”, and then he went away. When she got home, she told her father that she would like to go to the stadium with Fabrizio. Reno gave his permission, as long as the 11-years old brother Emanuele accompany Natalina. Fabrizio got the third ticket, and the three joined the match. Emanuele didn’t like football at all, so much that he spent all his time turning his back on the match! For the next years, Emanuele blackmailed his older sisters for that favor …

We may wonder: how Levati, a former amateur footballer for Pergocrema in Serie D (Italian 4th Division), had already gotten in touch with female football, a sport that had been born again in Italy only a few years before. Natalina herself understood the link just some years later. When Fabrizio was attending university, he was a friend of Patrizia Rocchi, one of the main footballers of that time. In order to spend some time with Patrizia, Fabrizio became vice-trainer of the teams for which the girl played: Sanyo Milano (season 1969) and then Gomma Gomma Milano/Meda (1970).

The Gommagomma Milano team winner of the 1970 Italian championship. Patrizia Rocchi is the the first from the right, standing

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serie_A_1970_(calcio_femminile)

Natalina is a very rich living source of stories about those trailblazers’ years. In the beginning, no Fiamma players were coming from Monza: they all came from Brianza, the country region northern to the city. Natalina says that her fellow citizens were so snob that they snubbed women’s football. Yet Reno used to volunteering at Mamma Rita, a charitable institution located in Monza managed by Catholic nuns. So he talked about the team with the mother superior: could football be an alternative, for those miserable girls? Natalina remembers: «That’s how twenty young girls arrived, in a single file … one nun leading, another one closing the line!”».

A Seventies Fiammanonza team

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

It was pioneering times, Natalina remembers. The first training pitch wasn’t a pitch at all, but a simple meadow provided by a players’ family: the dressing room was the family car box, and the players had to use their own training bags as goal posts!

Reno (1st), Natalina (2nd ), and Fabrizio (5th, standing from the left) with the team, on a pitch with improper grass

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

On the other hand, most of the very first Fiamma players, who weren’t so young (20, or 21 years old), really didn’t know anything about the football basics: Natalina herself had to teach them how to run straight with the ball, or what the penalty area was.

Such a swamp: and the match wasn’t even begun!

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

As secretary, Natalina was asked to talk with the wanna-be players, for the first interview. The first question was of course: “Why are you interested in football?”. Interviews could be very changeling. Once a 24-years old girl told her: “Last week my father died, eventually. He never allowed me to play football”. Natalina was shocked by those few words: “I was paralyzed, with the pen in my hand … Then I told her: you can say that finally, you can join our team, but please don’t say ‘eventually'”. After the father’s death, the mother of the young player inherited her husband’s negative attitude towards football: one night, when Natalina got a ride with the girl after training, she was attacked with … a bucket of water!

Fiammamonza players in green shirt, with a white-and-red stripe

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

In 1973 Natalina and Fabrizio reached a small country village, where the family of Mariangela Bonanomi (who was going to become the first Fiammamonza champion) lived. They would like to talk with her parents to convince them to permit Mariangela to play football, but Mariangela’s father welcomed them … with a pitchfork, blowing the spare wheel of Fabrizio’s sporting car!

Faces belonging to those who worked hard for their football dream …

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

The players who were still high school students used to ask newspapers not to publish their names and surnames: they were afraid their teachers would blame their lack of commitment to the school. Mothers used to be against their daughters’ love for football; fathers were almost absent; the only allies for those young footballers were their uncles or their boyfriends. Silvana Mazzoleni, one of the best Fiamma scorers of all time, used to say to her parents that she would go out with her boyfriend: in fact, he picked her to the practice, and then he asked his mother to wash Silvana’s uniform.

Silvana Mazzoleni (n. 9) in action

Source: https://www.facebook.com/groups/339574720193523/permalink/1103787920438862

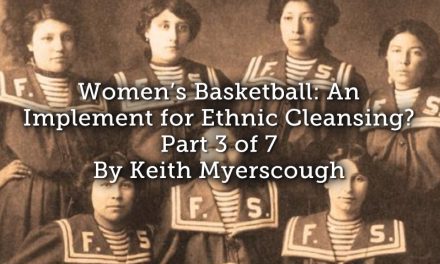

Mothers were full of prejudices, and Natalina spent a lot of time listening to their fears:

Will my beloved daughter ruin her beautiful legs? What about taking a hit to the breast? Does football preclude girls from having babies? Will my daughter become lesbian?

I asked Natalina how she could just work as a secretary, without playing. She confirmed: she never played, adding:

You know, my father was very open-minded, but that was a different matter: I was her daughter, I had to be the team’s secretary, playing … wasn’t appropriate

As this handwritten certificate commemorates

In 1979 Fiammamonza gained for their first promotion to women’s Serie A

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

Natalina, firstly as secretary and later (from 1979) as President of the club, talked a lot with the Fiamma players, especially the youngest ones, trying to convince them that football and a traditional vision of femininity were compatible. She told them they were not forced to cut their hair, as a lot of them used to do when they entered the team. During the 1970s and 1980s, it was not a matter of convenience (short hair meant faster shower), but of mentality. Mia Hamm made it.

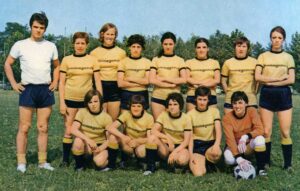

This Fiammamonza team wearing the yellow shirt was sponsored by Arte Grafiche Vertemati, a local graphic arts company located in Vimercate, near Monza

The photo was taken in the Seventies, as you can see from the fact that all players, except for the two goalkeepers, have short hair …

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

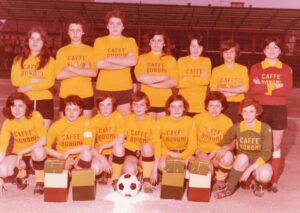

Also in this yellow shirt Fiammamonza team, only two brave footballers with long hair …

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

According to Natalina, during the 1990s Italian footballers met the new model coming from the States: all those college footballers were ponytailed! Following that successful model coming from abroad, the Monza footballers started to cut their hair. In order to explain how Mia and her US teammates were groundbreaking, Natalina, who joined the 1999 World Cup as President of the Italian women’s federation, revealed an anecdote that should be investigated by women’s football historians. According to her, the US players, who had accepted to take their earrings off, refused to do the same with their wedding rings off, as requested by regulation and the FIFA officers.

Three ponytailed players of the US National Teams that won the 1999 World Cup wearing their wedding ring

Source: https://twitter.com/calciatrici1933/status/1540990329230344193

In 1997 Natalina left the Presidency of Fiamma Monza, to become President of the Divisione Femminile, the women’s league ruled by Lega Nazionale Dilettanti (LND), the National Amateurs’ League. As president of the Women’s Division (1997-2009), Natalina fought for gender equality. At that time, a card that gave free access to any football stadium was given to any Italy’s Men National team member after the 25th cap. Natalina ensured that the card was given to the female players too, but then she run into a problem: none in Rome, due to the lack of historical documentation, was able to understand who had played more than 25 times with the Azzurre shirt! She had to reconstruct by herself this missing data, to decide which former players had the right to get the card.

- Natalina talking during a meeting Source: https://www.facebook.com/groups/339574720193523/permalink/1216878572463129/

-

As President of Divisione Femminile, Natalina pressents the first-ever Supercoppa Italiana to Carolina Morace

who in 1997 was playing for FC Modena Femminile

Source: Wikipedia.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/it/7/7c/Carolina_Morace_riceve_da_Natalina_Levati_la_prima_Supercoppa_1997_di_calcio_femminile.jpg

Up to this point, interviewing Natalina was useful to understand the birth and the early life of a women’s football club from the 1970s to the 1990s: but that wasn’t the reason why I had called her. I’m a sports historian focused on the Fascist era, after all. I would like to better understand the figure of his father Reno, and the link between Reno’s far-right political opinion and his activism for the development of women’s football. We live in the Megan Rapinoe era: in our mentality, women’s football is naturally liberal. How could those two elements, theoretically opposite, coexist in the same man? I was intrigued to discover the answer.

An older Reno Ceraso with captain Simona Consonni

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

Natalina described Reno as a good but authoritative father, very old-minded: he used to have dinner with his family always in a suit and tie. As typical of Southern men, he was very strict about her daughter: even the day before her marriage, the 28-years old Natalina wasn’t allowed to visit her friends’ houses with Fabrizio to give the wedding favors. On the other part, the father was very curious to listen to his 4 daughters and one son’s tales and opinions, although at the end he used to give the final sentence. As a present for her 18 years, Natalina was given Reno a FIAT 500: she was the only girl she knew in university who had her car.

In the 1960s Monza Reno and her wife Iride Cazzaniga (native of Monza) were both athletics judges. Natalina still remembers all these hours spent in Arena Civica (the city athletics stadium) in Milan, since her parents had not enough money for a babysitter: so Natalina could watch the athletic challenges of Italian champions such as Livio Berruti and Armando Sardi, who both joined the 1960 Rome Olympic Games.

An old Reno Ceraso (1st standing, from left) with the team

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

What about Reno’s past before the birth of Natalina? His father was a soldier during World War I: he died during the Spanish Flu pandemic. In 1925 the 10-years old orphan Reno, his mother, and his sister left the native Calabria village and moved to Monza, a wealthy city in the surroundings of Milan. In 1940, when he was just 25 years old, the Literature freshman Reno founded a private school located in Monza: later Iride started to teach Mathematics in Reno’s school.

Although during the regime he had no position in the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF) which he was a member of, Reno was a fervent Fascist. The young orphan Reno liked not only the regime’s support to sports but above all Mussolini himself, so much that he never accepted the fact that the Duce had a lot of lovers. Since after the Liberation some of his students wrote “Hail Mussolini!” on the blackboard, Reno was summoned by the partisans: despite his excuses, he was arrested as a sort of political revenge. From January to June 1946 he spent his time in San Vittore jail, in Milan. He was acquitted by a Communist judge because the simple fact of being a Fascist was not a crime. Since there was no more a student, Reno closed his school and left Milan with his wife (who was pregnant) and his 2-years old first daughter Natalina. The Ceraso family traveled all over the Italian peninsula by a camion, reaching the godforsaken village of Soriano, in Calabria. There, Reno founded a new school: he brought the family back to Monza only in 1957, Reno changed his teaching subjects from Literature to Physical Education; he started to play the judge during some athletics events, too. In 1960, Reno founded the sports club Reno Ceraso, joining the Centro Fiamma, the sports federation linked to the Movimento Sociale Italiano, the post-fascist party.

In a twist of fate, the street that leads to the stadium is dedicated to Davide Guarenti

an anti-fascist partisan born in Monza, who was arrested, taken in Fossoli concentration camp, and there shot by the Nazi soldiers in 1944.

Reno claimed not only the Fascist regime support to sports, but in particular to women’s sports: undaunted in his political faith, he used to say «You all condemn the Fascist regime, but during those years women used to go out, and they practiced sports!», quoting the example of Ondina Valla. «I was raised with this mentality: sports belong to everyone, including women», he used to say. As President of Fiammamonza, both Reno and Natalina decided not to mix football e politics. Although everyone knew about Reno’s political opinions, Fiammamonza always welcomed left-wing players, such as Milena Bertolini (whose grandfather had joined the Resistance, fighting in the Appennine mountains against the Nazi-fascists), and LGBTQI+ activist Elena Castellani.

In 1982, Fiammamonza played in the first edition of the National Women’s Football Cup

dedicated by the Centro Fiamma to Giorgio Almirante (1914-1988), the historic leader of MSI

still a controversial figure in present-day Italy

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

Milena Bertolini, coach of Italy’s National team from 2017 to 2023

For two seasons, from 1994 to 1996, she played for Fiammamonza, as defender

Source Wikipedia Commons

The history of Fiammamonza colors is very meaningful. The first-ever shirt was of course black, then changed to green because the club was given Centro Fiamma a free pack of volleyball shirts. For a while, another gift turned the color into yellow. Finally, even if Reno didn’t lack this “left-wing” color, around 1980 he decided to turn to red since Monza’s men’s team wore red and white: be closest as possible to the citizenship was more important than any historical or ideological issue.

The early Seventies

the original black shirts of Fiammamonza

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

The Centro Fiamma provided the volleyball green shirts that were used for football

but the two goalkeepers were still wearing black shirts

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

In 1975, Fiammamonza turned to yellow

Standing: Bocci, Lepri, Bettini, Apouani, Polenghi, Tartamella, Dassi, Petrocca.

Kneeling: Casalini, A. Mauri, Bassanini, Baracchetti, Merli Sala, Mainotti, Minichelli, Barbarini

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

When yellow met green …

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

The Fiammamonza which played its first season in Serie A (1980)

Standing: Appiani, D’Orio, Dassi, Caccia, Rotelletti, Strain, Romolo, Gariboldi, Tomè, Levati (coach)

Kneeling: Mainotti, Silva, Colzani, Castellani, Bonazzi, Brambilla, Mazza

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

Fiammamonza players in red shirt

taken from the historical archive of Fiammamonza club, courtesy of Natalina Ceraso Levati and Gaetano Galbiati.

For the same reason, the club crest became the Iron Crown, a historical symbol of Monza, linked to the medieval roots of the city, and to the female figure of Theodelinda. According to the local legend, the princess of the Lombards received the Iron Crown from Pope Gregory the Great and later donated it to the Cathedral of Monza.

The actual Fiammamonza logo, symboling the fusion with SC Juvenilia.

As the interview was coming to an end, Natalina talked me about the shock caused by his husband’s death. When Fabrizio died, in 1995, he was only 50 years old: Natalina was annihilated. She, who hadn’t the joy to become a mother, decided to devote all her person to Fiammamonza, seen as a sort of son: two years later, in 1997, she was elected President of the Divisione Femminile. She started to travel abroad as a UEFA delegate, opening her horizons:

After Fabrizio’s death, I don’t know what was going to happen to me, without football …

Later, when I took the first photos you’ve seen at the start of this article depicting the murals at the entrance of Sada Stadium, I reaslised what fruits came out of that hard decision.

During this 2023 Women’s World Cup, Italy’s National Team had two players who come from the Fiammamonza youth academy

Benedetta Glionna and Sofia Cantore. They were both born in 1999

Source: https://www.facebook.com/juveniliafiamma/?locale=it_IT

Benedetta Glionna (11), Arianna Caruso (18) and Sofia Cantore (7) wearing the Italy National team for 2023 World Cup

Despite of her young age, Cantore played in all the 3 matches of the group stage, against Argentina (from 74’), Sweden, and South Africa (from 83’)

Glionna was given by coach Bertolini the chance to play only the very few seconds of the third and last match of the Azzurre, which lost 3-2 with South Africa

Source: https://twitter.com/wernerludvik/status/1684443916274208768

For the original interview to Natalina Ceraso Levati, see:

https://www.academia.edu/82241869/Intervista_a_Natalina_Ceraso_Levati_23_06_2022_

For a sum of that interview, see: