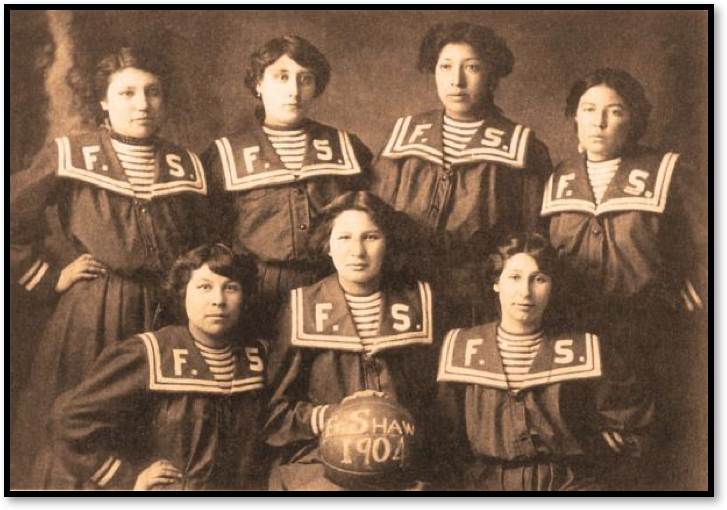

In 1904 a team of Native American girls from Fort Shaw Boarding School became basketball ‘champions of the world’. Their story is significant in the historiography of women’s basketball as the women’s game cannot simply be defined as the preserve of any one race, social class, or culture. In 1892 basketball was being used as a means to assimilate North America’s indigenous tribes into western society – the aim being to ‘break tribal loyalties, eradicate cultural traditions and move children away from their past’.

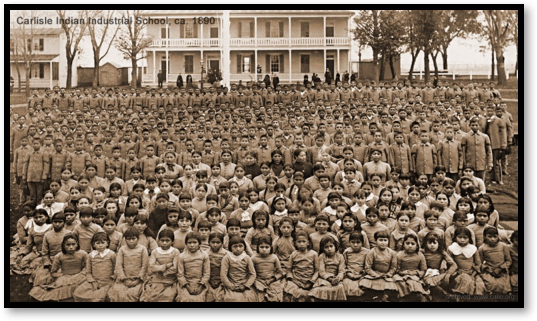

The story of the Fort Shaw girls’ basketball team began in 1892 when the abandoned US Army fort in Montana was opened as an off-reservation government school for Native American children. The scheme was part of an official US Government policy to ethnically cleanse the country of Native Americans by taking children from their families in order to strip them of their cultural heritage. They were made to wear ‘western clothes,’ speak only English and were taught a trade in preparation for their new lives. The ‘final solution’ was to achieve an ethnically homogeneous society through assimilation and acculturation. Colonel Richard Henry Pratt, the governor of the first Indian school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, declared that the aim was to ‘kill the Indian … [to] save the man.’

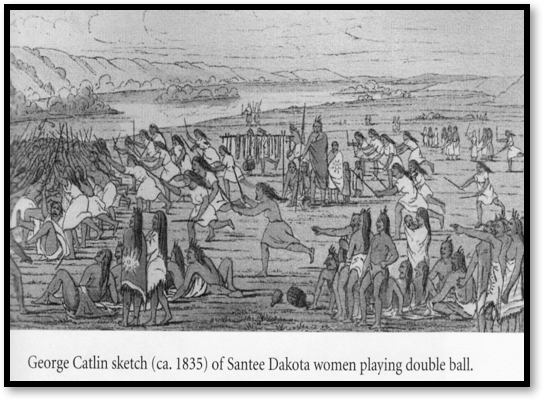

Josephine Langley, of the Blackfeet tribe, had trained as a teacher of physical culture at Carlisle Indian Boarding School where a major emphasis had been placed upon competitive team sports; the girls’ played basketball and the boys’ American football, baseball and athletics. Langley saw similarities between basketball and the Native American game of Double Ball. Both games had players to protect their own goal whilst attempting to gain possession of the ball in order to score in their opponent’s goal. In 1896, at the age of 19, Langley took up the post of instructor of physical culture classes for girls at Fort Shaw. Langley taught her girls’ classes the boys’ game of basketball as it offered the essential ingredients of being a skilful and fast moving game, with passing, dribbling and shooting.

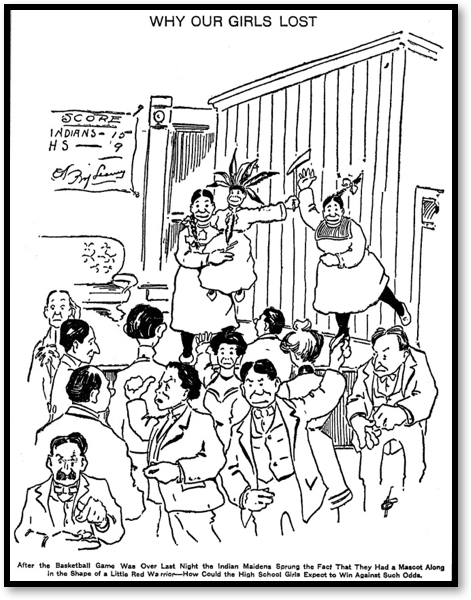

By 1899, the schools’ superintendent, F C Campbell, had directed the energies of the schoolgirls to public performances in playing the Mandolin, callisthenic exercises, and games of basketball. Campbell’s ‘whole purpose was to show to advantage the athletic abilities of Indian girls who had been taught to play a “white man’s sport”.’ The countless hours of practice came to fruition in late-1902 when the girl’s team played back-to-back away games over two nights. The first interscholastic game at Butte High School provided the Fort Shaw team with a steep learning curve both in terms of competitive team play and how the press and general public treated them as Native Americans. The local Anaconda Standard newspaper ran the headline, ‘White Girl’s Against Reds’, describing the Fort Shaw team as being made up of three ‘full-blood Indians and the others are half-breeds’; the girls felt confused and hurt by this inaccurate description. Fort Shaw won the first game 9-15, and lost the second 15-6, but the team’s popularity had raised the profile of the school and was to bring in much needed revenue from gate receipts.

In the summer of 1903, Fort Shaw had been invited to send representatives to the St Louis World Fair, also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, scheduled for 1904. Campbell decided to send his girls’ basketball team as they were not only State basketball champions but also accomplished in all aspects of the school curriculum. They were to be part of ‘a living exhibition’ that was designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the government’s ‘vanishing Indian’ education policy. The ethnological exhibits, on Indian Hill, would carefully juxtapose the lives of ‘primitives’ against that of ‘modern’ Indian students. The girls would demonstrate their skills in housework, music and basketball as part of the anthropological department’s contribution to the World Fair.

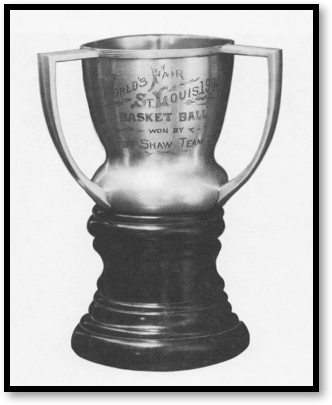

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat described the Fort Shaw girls movement on the basketball court in their twice-weekly games, for the 5 months they were in St. Louis, as being like ‘streaks of lightening … the fastest thing … ever seen in this city’. With the forthcoming St. Louis Olympic Games in August of 1904, the World Fairs ‘Anthropology Days’ took on added importance. The anthropology and physical culture departments endeavoured to promote the perception that many aboriginal natives from the four quarters of the world had a ‘natural athletic ability’, and that the Fair should be used to demonstrate their athletic prowess. The Fort Shaw girls’ basketball team were to exhibit their skills as a means to validate this hypothesis. The girls were split into two equal teams and played exhibition games in the Olympic stadium before thousands of spectators. In commemoration of their efforts, the St. Louis Physical Culture Department presented the Fort Shaw team with a silver trophy.

Whilst the Third Olympiad of the modern era was underway, from 29 August to 3 September 1904, a series of three girls’ basketball games had been organised for the champions of the World’s Fair. The first of the best of 3 game series took place on 3 September, against the St. Louis All-Star team, with the Fort Shaw team winning comfortably, 24-4; the Great Falls Tribune described the team’s ‘brilliant team work’, their ‘rapidity of a streak of lightning’, displaying a ‘fearlessness [that] completely non-plussed her opponents’. The second game was scheduled for 17 September, but at late notice the All-Star team asked for a postponement. The game eventually took place on 8 October, with Fort Shaw winning 17-6. Coach Stremmel, of the St. Louis All-Stars, complimented the Fort Shaw team, describing the girls as being ‘so skilful, so fleet, and … their powers of endurance are simply marvellous’. The Great Falls Daily Tribune eagerly declared the Fort Shaw team to be ‘the undisputed … world’s champions.’

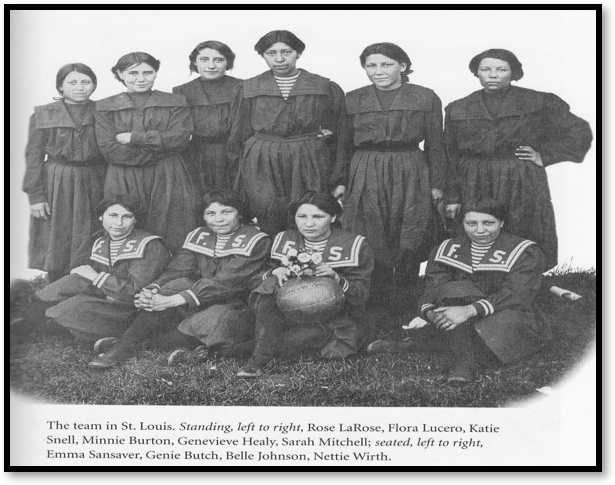

The ten girls on the 1904 Fort Shaw team brought their sporting heritage to the basketball court, sweeping aside the challenge of all teams put before them. The game, played under the boys’ rules, united the girl’s in a way no other activity had done – they represented 7 different tribes with their own language and heritage. The girls, aged 15 to 19, were from the Assiniboine (4), Gros Ventre (1), Lemhi Shoshone (1), Piegan (1), Shoshone-Bannock (1), Chippewa (1), and Chippewa-Cree (1) tribes. Each tribe had a strong tradition of female’s participating in sports; when combined with their physical strength and natural aptitude for physical exertion, the boys’ version of basketball proved to be an ideal game for the girls to play.

Article © Keith Myerscough