Please cite this article as:

Hess, R. ‘On the Field with the Coyness of Debutantes’: Uncovering the Hidden History of Female Footballers, In Piercey, N. and Oldfield, S.J. (ed), Sporting Cultures: Global Perspectives (Manchester: MMU Sport and Leisure History, 2019), 1-22.

ISBN paperback 978-1-910029-49-7

Chapter 1

______________________________________________________________

‘On the Field with the Coyness of Debutantes’: Uncovering the Hidden History of Female Footballers

Rob Hess

______________________________________________________________

Introduction

Academic interest in the history of women’s football is burgeoning.[1] This attention is not only apparent in a growing number of books, articles and postgraduate theses dealing with studies related to women’s participation as players in each of the world’s major codes, but it is also evident in recent conferences, exhibitions and displays of material culture associated with women’s football.[2] While numerous studies exist that examine various temporal and geographic contexts associated with particular codes of women’s football, notably soccer, this somewhat insular approach is beginning to be supplemented by a range of works that see the benefit in bringing together more transnational, and perhaps more nuanced, cross-code perspectives.[3] While this chapter is, in fact, focused on the experiences of one player in one code (Australian Rules football) during a very narrow time period, it does bear testimony to the increasing prevalence of the cross-pollination of narratives and methods associated with the history of female footballers.

However, despite a growing corpus of published material, explorations of women’s football (in the general) are still in their infancy and there remain substantial gaps in the theory, knowledge and understandings of when, why and how the various codes of women’s football emerged and developed (and sometimes stagnated) in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In this chapter, the main focus is around a case study drawn from the recollections and memorabilia of Myra MacKenzie, a participant with the Carlton Ladies Football Club in 1933.[4] The particular code is Australian Rules football, and observations related to the sometimes problematic and ‘hidden’ nature of biographical evidence associated with female footballers are used to draw conclusions and provoke discussion. However, while there is a recognition that the underlying gendered power relations which have helped make women’s football ‘invisible’ are problematic, in this case they serve as a stimulus to reveal, record and celebrate little known aspects of that history. The narrative also eschews a third person approach, adopts a conversational tone, and draws on some personal anecdotes to help illustrate the difficulties associated with biographical research.

Guiding reflections on these matters are the works of other biographers. While uncovering the ‘hidden history’ of female football players does not always involve or necessitate a full biography or documentation of a life history, since the primary and immediate focus is nearly always to understand the more narrow circumstances surrounding the involvement of girls and women in particular activities (namely a football match, a football season or in rare cases an entire football career), it is important to appreciate relevant methodological approaches. In particular, two apposite collections of papers have helped to inform my thinking about the methods and techniques, and the need for self-reflexivity, that continue to undergird my ongoing research into the historical experiences of female footballers. While there is a veritable industry that has generated a multitude of very helpful generic guides to oral history practices and the recording of life narratives, and provided erudite reflections on the ‘art’ of biography,[5] there is also a specialized group of scholars who have thoughtfully offered their insights into the relationship between sport and biography. In the instructive introduction to a collection of papers from a conference in 2001, John Bale, Mette K. Christensen and Gertrud Pfister raise a number of challenges for the reader. For example, they boldly claim that the distinction between ‘academic’ and ‘popular’ biographies is ‘somewhat spurious’, and they wonder why the published works on the lives of sports stars are routinely ‘de-politicised’.[6] Moreover, they suggest sports biographies ‘often fail to reflect a life but rather a career’.[7] Bale, Christensen and Pfister also distinguish between life histories and biographies, where the latter is often used to reveal ‘smaller history as a representation of the bigger history’, while a life history of ‘ordinary, usually unknown persons’ is potentially more complex, especially in terms of ‘space and relations’.[8] Moreover, as the editors note, Gertrud Pfister’s chapter in the book also raises the important question of how and why an author is drawn to their subject, and the extent to which the personality of the author ‘must find its way into biographical texts’ because there is ‘(almost) always’ a sense of admiration for the athlete being studied.[9] As Pfister herself disarmingly explains ‘I became aware that it was, and is, quite impossible for me [to] confront the “objects” of my scientific desires in a neutral and unemotional way. On the contrary…the individuals whose lives I studied forced their way into my life’.[10] Although Pfister admits that her published biographical works concentrate on two types of women, namely ‘the female adventurer and the “feminist” sports leader’,[11] her reflections resonate beyond the case studies she describes.[12]

In another collection, arising from a conference on ‘Sporting Lives’ at Manchester Metropolitan University in 2010, the array of contributors is impressive, and the brief introduction by editor Dave Day highlights a major thread that run across the chapters. What is particularly evident, notes Day, is not only a recognition that the writing of biographical works is challenging, but the observation that so many levels of veracity can pervade the narrative of an individual’s life.[13] His conclusion is that ‘taken together these papers highlight the richness and diversity of sporting lives as well as demonstrating that these stories can never be entirely finished but will continue to evolve as further sources are uncovered’.[14] With some of the papers and underlying themes and issues raised in the two collections mentioned above in mind, a broader context for the discussion of the evidence and testimony surrounding the experience of one female Australian Rules footballer is provided.

Serendipitous beginnings

One of the joys of being an academic is the freedom to be able to research about, and sometimes even teach about, topics that have a personal interest. So when I developed an attentiveness to the history of women’s Australian Rules football arising from some incidental research that was completed on the topic as part of my PhD it was not difficult to share some of those findings with my students through a number of sport history units that I was involved in teaching at Victoria University.[15]

Hence, during the 1990s (in the years before the widespread digitization of newspapers) it was not uncommon for me to talk anecdotally in lectures about my ongoing (unfunded) research on the history of women’s football, sharing my incremental discoveries over the years with the students. As I explained to them, it seemed that the earliest references to women playing football in Australia occurred in Perth during the Great War, and there was also evidence that some games were played across Australia in the 1920s, as well as just after World War II. Newspaper reports also revealed a number of incidents related to women playing football during the 1950s and 1960s. This fragmented and discontinuous timeline, I suggested, eventually led to the formation of the first ongoing women’s football competition in Australia, the Victorian Women’s Football League (VWFL), which was established in Melbourne in 1981. I also attempted to make a few cross-code comparisons, noting, for example, that there never seemed to be any official ban on women playing Australia Rules football, as there was in England when, in December 1921, the Football Association banned women from using any of its grounds to play soccer, a ban which lasted for almost 50 years. But the details on women playing Australian Rules were, I explained, very patchy, with specific games and players seemingly excluded from official histories of the code. Forlornly, I declared that not much was known about the involvement or background of individual players, the circumstances under which they played, or the context in which games took place. Therefore, these particular classes would end with an appeal for students to contact me if they had any leads I could follow.

Occasionally, but not very often, responses were received from students on the basis of my intermittent pleas. I especially remember one occasion in 2003 when a slightly older student, Peter Jurkovsky, came to see me in my office after a lecture when I had talked about my research on women’s football. He revealed that his elderly neighbour had told him she used to play football for Carlton (one of the current elite Australian Football League [AFL] teams), back in the 1930s, and that she possessed some photographs. This was serendipity at work, for this student eventually introduced me to Myra MacKenzie, later to be identified as probably the oldest living female footballer in the country, who was happy to be interviewed and had some memorabilia to share. In my view, there is no doubt that the interactions engendered by personal contact in face-to-face classes was a contributing factor to the uncovering of previously hidden material about women’s football in Australia.[16]

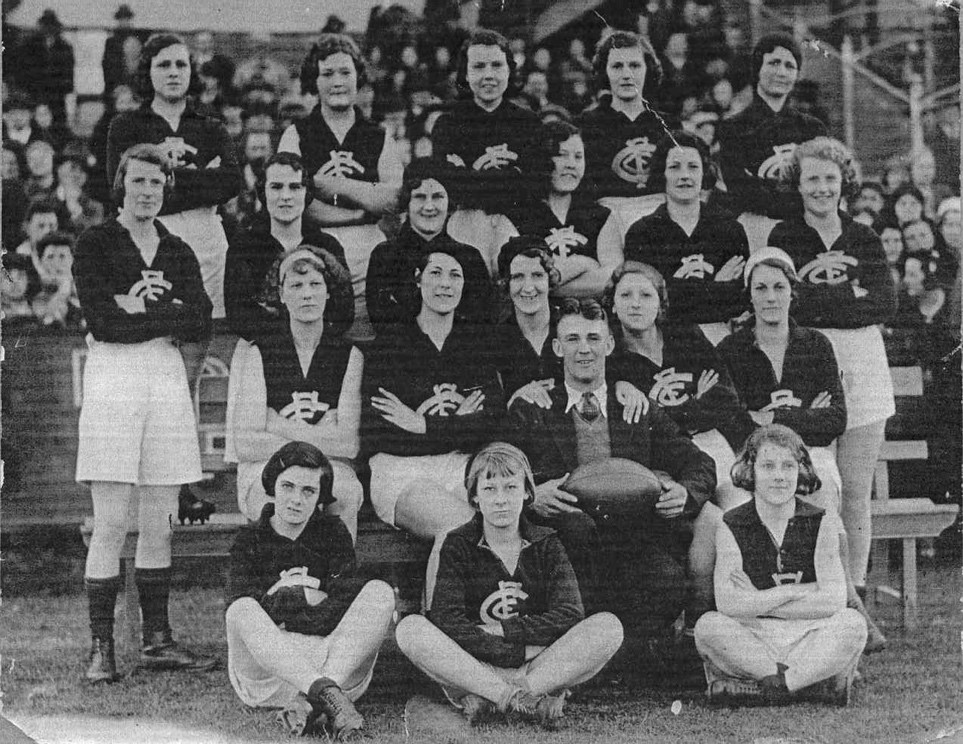

Figure 1. ‘The Carlton Ladies’ Football Team’, prior to a match at Princes Park, 1933.

Myra is seated to the left on the ground in the front row.[17]

Around this time, other scholars were beginning to explore aspects of women’s involvement in Australian Rules football, with three PhDs completed within the decade. In 2001, Nikki Wedgwood explored the ethnographic and gender dimensions of female (and male) players.[18] Five years later, Debbie Hindley examined the culture of women in football, including their roles as spectators, administrators and players.[19] And in 2008, Peter Burke devoted a substantial part of his PhD thesis on the history of workplace football to the beginnings of the women’s code among employees of department stores in Perth during World War I.[20]

Figure 2. ‘The Carlton Ladies’ Football Club’ in a studio photograph, 1933.

Myra Mackenzie is seated on the left in the front row.[21]

Carlton Ladies Football Team who played Richmond Ladies on the Kings Birthday Holiday 3/7/1933. Micky Crisp was the coach (Carlton Captain). Charity Day (30,000) attended. Part was shown on MovieTone News in Theatres.[22]

Here, or so it seemed, was some vital information, namely a date for the game, the identity of the Carlton team’s coach (Micky Crisp), details of the opposition team (Richmond), a crowd estimate and a statement attesting to the fact that there was film footage of the game and that this film was later shown in theatres. At this point in my research, I was well aware that in 2003 not a single elite AFL team had made any reference in any of their official club histories to any support for female football teams in the past. And yet here was what seemed like incontrovertible evidence that the Carlton and Richmond clubs had supported a women’s football game in 1933 that drew a crowd of 30,000 people. Also supplied for perusal was a framed studio photograph of the Carlton team (featuring the designation of the team on the ball), but without a caption or annotation (see Fig. 2). In addition, included as part of the collection, was a photograph of Myra’s basketball team, featuring a handwritten caption on the reverse. The annotation stated that this was an image of the ‘Hoadley’s 3XY Basketball VII’, who ‘Won the night premiership at Worths [sic]’, with a later note (in different ink) adding ‘1936 or 7’, and listing three or four first names of the group pictured (see Fig. 3). Myra is clearly identifiable, third from the right, as are the player badges identifying the competition.[23]

Figure 3. Basketball (Netball) Team, Hoadleys’ 3XY Night Competition Premiership Winners, Melbourne, c. 1936.

Myra is standing third from the right, behind a fellow player and the team’s young mascot.[24]

Meeting Myra

Whether it was the confusion and uncertainty caused by discovering that aspects of Myra’s records were misleading, or the desire to conduct more extensive newspaper searches, or simply the pressures of other work commitments, time slipped by. Whatever the case, it was quite a while before either Wedgwood or I could pursue our research agenda with Myra, although our catalogue of some other matches played by women in other decades continued to grow, and in 2005 Wedgwood and I co-edited a special issue of Football Studies devoted to research on women and Australian Rules football.[26]

Eventually, following ongoing discussions with Wedgwood, who was based in another state at the University of Sydney, we realized that time was slipping by for Myra as well, who was approaching her ninetieth year. After Wedgwood conducted a pilot telephone interview with Myra, from which eight pages of themed notes were generated, we then made arrangements for a face-to-face meeting with her in May 2007. Our preparation involved devising some additional interview questions, and setting up a day and time to meet Myra at her home in suburban Melbourne. What transpired that day changed my thinking about the strengths and weaknesses of oral history, and challenged my attitude about the difficulties associated with researching women’s football.

While we arrived with a set of specific research questions in mind related to women’s football, it was agreed that we should try to flesh out the life history approach that Wedgwood had initiated in her pilot interview. We envisaged that this would allow us to more fully understand the social and historical context of Myra’s experience, rather than having a narrow focus on the who, what and when of women’s football, even though such factual information was important. Below are some very brief aspects of the findings, based on the notes compiled by Wedgwood after the interview, supplemented by some feedback that I provided.[27]

Myra was born in Tenterfield, NSW, near the Queensland border, in 1917, the second eldest child in a family with four male and four female children. They moved to Melbourne when she was 12, where she first saw football played, and she later learnt book-keeping before working in her father’s importing business as a delivery girl for shoe buckles, about the time she played in the football match. She later married and had three children before her first husband died 10 years into the marriage. She later re-married. Myra’s father loomed large in her upbringing, and he was an active rugby player until he was 50. He also coached and played cricket, encouraging his eight children to be active in cycling, cricket, swimming, boxing, basketball (netball), hockey and athletics, none more so than Myra who claimed that ‘my father took me to every sporting event there ever was’.[28] In fact, Myra lived opposite the Carlton football ground, and would watch the male Carlton footballers train twice a week.

As for the women’s football game, Myra claimed that her father saw an advertisement in the newspaper for girls and women to be in a football match as part of a carnival and he encouraged her to try out. She says that about 70 females turned up at training and over several weeks the squad was eventually trimmed down to those who were picked to take the field. Myra, who had just turned 16 before the match was played, said most of the team were older than her, some by 10 years or more, with just one other player, Violet, younger than her. None of the females on the team were married according to Myra. She also claimed only one other player on her team was actually local, with the others coming from distant suburbs. This assertion might help explain the slightly different personnel in the second framed studio shot that Myra had in her possession. She says that the photograph was taken several days after the match, and not all the girls in the image actually played in the match, noting that 19 players are featured at the ground, but there are only 18 players in the studio shot. A subsequent close examination confirms that of the 19 females photographed on the day of the match, only 11 or 12 feature in the studio photograph. In other words, six or seven of the women in the studio portrait seem to be ‘stand-ins’, possibly players from the larger training squad, who were called upon to ‘make up’ the numbers for the more formal photograph. Not surprisingly, Myra had trouble remembering or identifying a large number of her team-mates, although she did recall seeing one player regularly on a tram route, noting that she was a train conductress.

Notwithstanding the confusion of playing personnel, Myra also related that the players in her team (presumably the actual players, not the photographic ‘stand-ins’) were all presented with individual cups at a presentation night at a local theatre. This is verified by a press report which stated: ‘A silver cup will be presented to each member of the Carlton girls’ football club, which defeated the Richmond girls in a thrilling game at the carnival last Saturday, during the Carlton club’s picture night next Monday evening’.[29] It was not surprising to find that Myra had kept her trophy in her possession for more than 70 years, proudly showing it off during our visit. However, the inscription at the front of the cup was problematic to say the least, and possibly explains the confusion about the date of the match. The inscription reads as follows:

Presented By

Carlton Football Club

To Myra Mackenzie

Carlton Ladies v Richmond Ladie

3.7. 1933

Given that the match actually took place on August 12, 1933, the inscription on the trophy is clearly incorrect, and one can only speculate about the reasons for this error. It is highly unlikely that the game was originally scheduled for Monday, July 3, 1933 (a normal working day), especially since a public holiday to celebrate the birthday of King George V had already been declared and celebrated on Monday, June 5, 1933. A possible scenario is that the cups were made and inscribed with the names of the selected players in advance, but that the wrong date for the match was engraved on the trophies. Whatever the case might be (and the evidence is confusing), then it is probable that the incorrect inscriptions on the cups (commemorating a match on July 3) were not altered or fixed, perhaps due to cost-saving reasons. Therefore, incorrectly inscribed trophies were presented for a match that took place in August rather than July. However, there is no mention of the change of dates in the press, and Myra seemed unaware of the discrepancy, especially since she had no relevant newspaper clippings in her possession. In such circumstances, at some later time, Myra might have unwittingly transposed the incorrect date on the cup to the back of her photograph, forgetting that the match had possibly been postponed and genuinely believing that the game had in fact taken place on July 3, 1933. When the records and memories of an elderly interviewee do not match the evidence possessed by the researchers it can become a delicate if not awkward situation, and in this case we declined to press Myra on this particular, though very significant, discrepancy.

Two other important matters were raised in the interview, bearing in mind that the press coverage of the match had been minimal based on an initial search of the microfilm. ‘What about the opposition?’, we asked, and ‘Who were the Richmond Ladies you played against?’. Myra declared that the team they played against was made up of girls and women from the Bryant and May factory, a match manufacturing business located in Richmond. In some ways this was not surprising, since the template stemming from Burke’s work on the origins of the women’s code in Australia was that workplace-based female football teams would often be involved in charity matches.[30] However, none of the press sources mentioned that it was women from Bryant and May who were involved in the match on August 11, 1933. Myra’s revelation was important, as subsequent research has revealed that Bryant and May were an off-shoot of a British Quaker firm who believed in providing and encouraging a multitude of recreational and sporting activities for their employees during and after working hours, which was also the case at the Richmond factory, the largest match-making firm in the country. In fact, the company went out of its way to provide on-site recreational facilities for its employees during the 1930s, encouraging them to participate in sporting competitions across Melbourne.[31] While evidence of a female Bryant and May football team has not yet been uncovered, it may exist in a vast archive of company material stored at the State Library of Victoria or in yet to be digitized newspaper sources.

The second matter was the Movietone newsreel mentioned in the caption on the back of Myra’s 1933 team photograph (or the ‘Cinesound’ newsreel as she referred to it in the interview). Myra confirmed that she had seen the footage at the presentation night when trophies were presented. Given the fact that no copies exist of the earliest known ‘moving picture’ of a ‘Ladies’ Football Match’ that was ‘specially taken’ for the Wondergraph Theatre in Adelaide on September 3, 1918, it was obvious that the discovery of a Movietone newsreel from 1933 would be a significant find.[32] Accordingly, Wedgwood and I later visited the extensive collection of the National Sound and Film Archive in Canberra, but there was no record of such newsreel footage in their archives. There was, however, an illuminating postscript to this aspect of the research. Was the match filmed, as Myra suggested, and later viewed in cinemas, if so making it perhaps the earliest known movie-quality footage of women playing football in Australia? In this case, serendipity was once again at work, or maybe it was just the benefits that come from like-minded academics networking together. Tony Collins, the doyen of rugby historians, had made several conference trips to Australia, and had obviously gleaned quite a deal about Australian Rules football from the papers he heard and the research he had conducted when visiting at various times between 2005 and 2008. He therefore knew of my interests in the history of women’s Australian Rules football from presentations I had made at the same conferences and material that I had published. On March 31, 2008 he began sending me a series of notes attached to emails on other matters: ‘…Incidentally, you’ve probably already seen it but I’ve dug out some film of the 1933 Carlton v Richmond women’s match. I will bring it along with me (interestingly enough, in the catalogue the film is described as women’s rugby!)’; ‘I’ve attached the file of the … women’s match. It’s from the Pathe News UK [United Kingdom] website, and filed under “rugby’”; ‘Glad you liked the footage. That’s all there is that I could see … [T]he editors obviously couldn’t tell the difference between the codes!’.[33] It is little wonder that the footage could not be easily found when it was labelled as an ‘all-women’s Rugby match’ and filed amongst a news archive in the UK.

The clip lasts for just 63 seconds, but it does include some footage of Myra (wearing number 28) in action. The excerpt also confirms that the crowd watching the match was substantial, with what seems to be packed grandstands. While Myra’s handwritten annotation on the back of her team photograph (‘Charity day [30,000] attended’) may have been her own estimation of the crowd, at least one press report gave a figure of 10,000 spectators.[34] The variation may be explained by the fact that the women’s match was part of a lengthy carnival program staged in order to raise funds for a charity, so the approximation of the crowd might have been dependent on the time of day that spectator numbers were calculated. The opening titles for the clip are also revealing in that they refer to ‘a big and highly amused crowd’.[35] No matter what the crowd size might have been, the sexist language and patronising tone used in the voiceover for the clip (reproduced below) is typical of the newsreel genre during the middle decades of the twentieth century (and perhaps beyond), and was a style often used in contexts other than the portrayal of sport.

The battle of the Amazons. Eighteen Richmonds on the field with the coyness of debutantes. Must be their first ball. Now make way for the Carlton Colleens – 36. A perfect 36. Dainty ankles are hidden in their big brother’s boots. Now then, no roughness girls. Whoa, this isn’t a bargain sale. Sylvia’s got the ball. That’s Sylvia in among the feet. Go on 21, they won’t hurt you. All on the ball, the full-back is the only one in position and her bootlace is undone. Nicely saved Sir … err, Madam. Ahh, that’s tricked ’em. Ah, she’s got a way with her. That’s it, get rid of it, get rid of it. Aha, good mark and what a kick – fully 10 yards. Hey, what’s wrong with the umpire? Oh, they’re not taking any notice of him, he’s only a man. Hello, what’s happened here? Smelling salts, quick![36]

As Mike Huggins notes in his nuanced observations of the phenomenon in the UK between the wars, the discourse associated with ‘various representations of women’s sport found in images and commentary’ has a ‘complex, subtle and problematic nature’.[37] This is especially relevant given the assertion by Huggins that representations of sport in this medium were socially significant. That is, ‘wider public attitudes to women’s sport were partly shaped by the newsreel companies’ pre-selected images and the ways presentation was framed’.[38] In general, says Huggins, newsreels from this period ‘…presented a hegemonic, patriarchal male discourse to a majority female audience’.[39] More specifically, though, he surmises that ‘The gendered nature of newsreel coverage of sport helped to define, reflect, normalize and influence the way audiences thought about women’s sport’.[40] The packaging of the Carlton versus Richmond women’s game for cinema audiences seems to fit with the broader analysis offered by Huggins, especially given that incursions by women into male-only territory are frequently characterised by belittling or demeaning commentary. As an aside, it also worth noting that while the opening titles of the 1933 British Pathé News clip imply that the scenario of women playing soccer might ‘perhaps’ be acceptable, the notion that ‘Melbourne Amazons’ would take part in Australian Rules football (mistakenly referred to as the ‘first all-women’s Rugby Match’) is presented with mock indignation.

In the end, we thanked Myra for the interview, presented her with a small gift, and left her home pleased with the additional information we had gleaned, but still with some nagging doubts about some aspects of the story. In 2007 Myra was in in fairly good health for an 89 year old, and was still able to attend games played by her beloved Carlton Football Club on a regular basis. It was not unreasonable to think that a follow-up interview with her could have been arranged in the future. In fact, following the interview and based on further research, we did send her some newspaper reports of the game (including a full-page photographic collage from the carnival day which featured in the Leader newspaper), and in July 2008 we sent her the film clip of the match that had been uncovered. Sadly, however, we lost contact with Myra after she moved from her house and to our regret we never did a follow-up interview, despite the fact she lived for almost another 10 years.

A counter narrative

Like many women prior to the advent of the VWFL in 1981, Myra was only given the opportunity to play one formal game of Australian Rules football. Despite the considerable fanfare surrounding the Carlton versus Richmond match in 1933, and a sizable sum raised for charity during the Great Depression, Myra says she was not aware of any other games played by the Carlton or Richmond teams in future seasons and she never took part in another match during her lifetime.[41] Hidden away in one newspaper report was the fact that on the same day as Myra’s game, and just a few kilometres away, the North Melbourne Football Club also staged a carnival to raise funds for charity. Three football games took place, including one involving ‘teams of girls’. According to the Age, ‘One was the North Melbourne Women’s FC and the other a side drawn from the Women’s Athletic Club’, with the former winning by two points. Dick Taylor, the coach of the senior men’s team, was the umpire.[42] Clearly there was enthusiasm for the code by female players, but it seems that the Victorian Football League clubs saw little need or opportunity to continue to foster such games, once the charity purposes of isolated, once-off novelty matches had been met. There was certainly no speculation in 1933 that a round-robin series between the various women’s teams in Melbourne would be played, as later happened in 1947 as part of the post-war ‘Food for Britain’ appeal.[43]

Figure 4. An action scene from the Carlton versus Richmond match at Princes Park, Carlton, August 11, 1933.

Myra MacKenzie (number 28) has her back to the camera.[44]

Figure 5. Richmond players having oranges during the half-time break of the match at Princes Park, Carlton, August 11, 1933. [45]

Aftermath

The instructive aftermath to the above narrative involves a brief assessment of how the media and the Carlton Football Club responded to the ‘discovery’ of Myra’s football ‘career’, as well as my reflections on how she has been written into the national history of the code. In March 2006 I wrote a review of Jean Williams’ book, A Game for Rough Girls, and concluded the review with several asides to women’s football in Melbourne during the 1930s, suggesting that the book by Williams would be a good methodological starting point for international cross-code comparisons. As the executive editor of the publication in which the review appeared, I also chose to include the studio portrait of Myra’s team on the front cover of the Bulletin of Sport and Culture, a magazine-style periodical that was distributed free-of-charge twice a year to more than 600 academics, postgraduate students and the media.[51] As a result of this exposure, over the next few years Myra became something of a minor media celebrity in Melbourne, as print and radio journalists, along with the Carlton Football Club chased her, and/or me, for interviews about her involvement in women’s football. For instance, in 2007 Martin Flanagan, a leading football writer for the Age, wrote a full-page feature on Myra’s playing experience, and her continued devotion to the club. He also quoted from the Leader newspaper of 1933, and prised some other incidental reflections from Myra.[52] In 2010, Myra, then aged 93, was interviewed by Gary Tippet from the Sunday Age, but this time the lengthy feature appeared in the general news section rather than the sports section. Myra again recalled incidents from the 1933 match, and Tippet contextualized the game in terms of the phenomenal growth of the women’s code in the opening decade of the twenty-first century.[53]

Despite the fact that respected academic Lionel Frost published a solid history of the Carlton Football Club in 1998, it was not until 2009 that any publications by the club made mention of Myra or women’s football.[54] In Out of the Blue: Defining Moments of the Carlton Football Club, former journalist, now a museum manager at the club, Tony de Bolfo devoted two pages to Myra’s story. Myra again recounted her memories of the game, adding some new details not previously revealed (such as her recollection that the Carlton captain, Merlene, was the ‘head of a cycling club’, and that there were many ‘basketballers’ in the team), but de Bolfo repeated her (incorrect) assertion that the game took place on a Monday public holiday.[55]

The sesquicentenary of Australian Rules football in 2008 also allowed several co-authors and I to insert brief details of the Carlton versus Richmond women’s game (and related photographic images) into a much broader narrative history, a rare occasion that instances of women playing football had been integrated into an academic monograph framed against the backdrop of the development of the national code.[56] Even more poignantly, in 2016, on the eve of the very first season of the AFL’s national competition for women, a colleague, Brunette Lenkić, and I were able to include much more extensive and nuanced detail about Myra’s story into a national history of women’s Australian Rules football.[57]

Featuring Myra in the book was not only a fitting tribute to the valuable lessons learnt from uncovering her hitherto ‘hidden’ history, but a salutary reminder about the necessity for the triangulation of fragmentary, sometimes contradictory, evidence, especially where women’s football is concerned. Prior to the formation of the VWFL in 1981, women’s football was, by and large, not taken seriously as a sport, and once the novelty of female matches had worn off or the charitable purpose for games had dissipated, the enthusiasm by the participants for regular season fixtures or even annual matches was soon derided or dismissed by those in control of football’s resources. In this situation, where games were sporadic at best, often opposed by male and female critics alike, and not always well reported (if covered by the media at all), it is not surprising that the records associated with women’s matches are not only sparse but are sometimes not even regarded as having historical value. Given this deep archival abyss, it is extremely important that the artefacts, records and oral testimony related to all codes of women’s football should continue to be exposed, interrogated, and contextualised. For as Myra’s case illustrates, although the journey involved in researching the lives of female footballers may be serendipitous, if not arduous and time-consuming, it can also be rewarding.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is expressed to my colleague, Nikki Wedgwood, for her wisdom, guidance and advice concerning the ‘hidden’ history of female footballers, and for her valuable feedback on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

[1] Difficulties associated with the gendered descriptor of ‘women’s football’ are acknowledged. For a brief discussion of the debates around nomenclature, see Jean Williams and Rob Hess, ‘Women, Football and History: International Perspectives’, International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 18 (2015): 2117-2118. For a general philosophical discussion concerning the rise of female leagues in sports traditionally played by men, see Michael Burke, ‘Is Football Now Feminist? A Critique of the Use of McCaughey’s Physical Feminism to Explain Women’s Participation in Separate Leagues in Masculine Sports’, Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 22, no. 3 (2019): 499-513.

[2] It is not feasible to list all the relevant literature here, but a small sample taken from various codes in a publishing sequence spanning two decades gives a sense of the variety and scope of the foundational research being undertaken. See Gertrud Pfister, ‘Reconstructing Femininity and Masculinity in Sport – Women and Football in Germany and France During the Inter-War Years’, Cultural Diversity and Congruence in Physical Education and Sport, eds. Ken Hardman and Joy Standeven (Aachen: Meyer and Meyer Sport, 1998), 81-100; Alethea Melling, ‘Charging Amazons and Fair Invaders: The 1922 Dick, Kerr’s Ladies’ Soccer Tour of North America – Sowing Seed’, in Europe, Sport, World: Shaping Global Societies, ed. J. A. Mangan (London: Frank Cass, 2001), 155-180; Jean Williams, A Game for Rough Girls? A History of Women’s Football in Britain (London: Routledge, 2003); Peter Burke, ‘Patriot Games: Women’s Football during the First World War in Australia’, Football Studies 8, no. 2 (2005): 5-19; Jonathan Magee, Jayne Caudwell, Katie Liston, and Sheila Scraton, eds, Women, Football and Europe: Histories, Equity and Experiences (Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport, 2007); Andrew Linden, ‘Revolution on the American Gridiron: Gender, Contested Space, and Women’s Football in the 1970s’, International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 18 (2015): 2171-2189; Jennifer Curtin, ‘Before the “Black Ferns”: Tracing the Beginnings of Women’s Rugby in New Zealand’, International Journal of the History of Sport 33, no. 17 (2016): 2071-2085.

[3] For a brief discussion of some of the challenges inherent in cross-code approaches, see Williams and Hess, ‘Women, Football and History’: 2115-2122. See also Katherine Haines, ‘The 1921 Peak and Turning Point in Women’s Football History: An Australasian, Cross-Code Perspective’, International Journal of the History of Sport 33, no. 8 (2016): 828-846.

[4] MacKenzie was the subject’s maiden name. She returned to using this surname after changing her name in two subsequent marriages. In this chapter her first name is used as the prime designation, partly to avoid any confusion between her married names, but also to reflect the personable relationship built up between the researchers and the subject.

[5] For a small sample of some of the relevant academic literature, see L. M. Smith, ‘Biographical Method’, Handbook of Qualitative Research, eds. Norman Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994): 286-305; Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson, Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives, 2nd ed. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001); Joanna Bornat and Hanna Diamond, ‘Women’s History and Oral History: Developments and Debates’, Women’s History Review 16, no. 1 (2007): 19-39.

[6] John Bale, Mette K. Christensen and Gertrud Pfister, ‘Introduction’, Writing Lives in Sport: Biographies, Life-Histories and Methods, eds. John Bale, Mette K. Christensen and Gertrud Pfister (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2004), 9-10.

[7] Ibid., 10. Emphasis in the original.

[8] Ibid., 11.

[9] Ibid., 14.

[10] Gertrud Pfister, ‘We Love Them and We Hate Them: On the Emotional Involvement and Other Challenges during Biographical Research’, Writing Lives in Sport: Biographies, Life-Histories and Methods, eds, John Bale, Mette K. Christensen and Gertrud Pfister (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2004), 131.

[11] Ibid., 135.

[12] Ibid., 140-142; 142-145.

[13] Dave Day, ed., ‘Introduction’, Sporting Lives (Crewe: Manchester Metropolitan University Institute for Performance Research, 2011), i.

[14] Ibid. For worthwhile related discussion of methodologies associated with biography, prosopography and oral history, see, especially, Samantha-Jayne Oldfield, ‘Narrative Methods in Sport History Research: Biography, Collective Biography, and Prosopography’, International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 15 (2015): 1855-1822, and Fiona Skillen and Carol Osborne, ‘It’s Good to Talk: Oral History, Sports History and Heritage’, International Journal of the History of Sport 32, no. 15 (2015): 1883-1898.

[15] My PhD was the first ever doctoral study devoted exclusively to the history of Australian Rules football. See Rob Hess, ‘Case Studies in the Development of Australian Rules Football, 1896-1908’ (PhD diss., School of Human Movement, Recreation and Performance, Victoria University, 2000). This thesis contained a major case study that examined the unique role of female spectators in Australian Rules football. Female players were only mentioned briefly in passing.

[16] Other students also alerted me to relevant material that they came across in unrelated press searches for other assignments. Subsequently, two undergraduate students went on to complete Honours degrees on the history of women’s Australian Rules football under my supervision. See Kathryn Sinclair, ‘“Who Won? Who Cares?”: Media Coverage of Women Playing Australian Rules Football in Melbourne During 1947’ (Honours diss., School of Sport and Exercise Science, Victoria University, 2009), and C. E. Leach, ‘Female Patriots: Women’s Participation in Australian Rules Football in Victoria During 1943’ (Honours diss., School of Sport and Exercise Science, Victoria University, 2010).

[17] Image courtesy of Myra MacKenzie.

[18] Nikki Wedgwood, ‘We Have Contact! Women, Girls and Boys Playing Australian Rules Football: Combat Sports, Gendered Embodiment and the Gender Order’ (PhD diss., Faculty of Education, University of Sydney, 2000).

[19] Deborah Hindley, ‘In the Outer – Not on the Outer: Women and Australian Rules Football’ (PhD diss., School of Communication Studies, Murdoch University, 2006).

[20] Peter Burke, ‘A Social History of Workplace Australian Football, 1900-1939’ (PhD diss., RMIT University, 2008).

[21] Image courtesy of Myra MacKenzie.

[22] Punctuation for the handwritten annotation is not clear on the original note, as there are flecks and marks on the paper stock which may or may not be full-stops. For the purpose of readability, punctuation has been added by the author.

[23] In Australia, the sport of netball was known as women’s basketball until 1970. Note the hoop without a backboard in the background.

[24] Image courtesy of Myra MacKenzie.

[25] See the Sporting Globe (Melbourne), August 12, 1933, and the Age (Melbourne), August 14, 1933. Another report noted that the game began half an hour behind schedule, which might account for the reduced timeframe of the match, given that games usually consisted of four quarters rather than two halves. The same report also recorded that ‘The Richmond team took the field accompanied by an Irish setter mascot’. In addition, it was observed that ‘The girls had no qualms about putting plenty of vigor into their game. They bowled one another over with merry abandon’. See the Herald, August 12, 1933.

[26] See especially: Burke, ‘Patriot Games’; Rob Hess, ‘“For the Love of Sensation”: Case Studies in the Early Development of Women’s Football in Victoria, 1921-1981’, Football Studies 8, no 2 (2005): 20-30; Nikki Wedgwood, ‘We Have Contact! A Comparative Analysis of the Development of a Schoolgirl Australian Rules Football Competition with a Women’s League’, Football Studies 8, no 2 (2005): 31-50. In my paper, I made a brief but specific reference to the Carlton versus Richmond match in 1933 for the first time in a published work, citing Myra MacKenzie as a source.

[27] Nikki Wedgwood (with assistance by Rob Hess), ‘Interview Notes: Myra MacKenzie and the Carlton Ladies Football Team, 1933’, May 11, 2007.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne), August 18, 1933.

[30] See, for example, Peter Burke, ‘Football and the Workplace: A Brief History of Workplace Australian Football, 1860-1939’, Football Fever: Grassroots, eds. Bob Stewart, Rob Hess and Matthew Nicholson (Hawthorn: Maribyrnong Press, 2004), 51-66, and Peter Burke, ‘Workplace Football and Industrial Recreation in the First World War’, Victorian Historical Journal, 86, no. 1 (2015): 187-206.

[31] For a history of match manufacturing companies in Australia, including details about the work practices and philosophies associated with the Bryant and May company, see Jerry Bell, Lighting up Australia: The Story of the Australian Match Manufacturing Industry, 1843-2003 (Armadale: Jerry Bell, 2008).

[32] See an example of an advertisement spruiking Wondergraph Theatre’s ‘exclusive’ ‘moving picture’ of two women’s football matches in the Register (Adelaide), September 3, 1918.

[33] Email correspondence from Tony Collins to Rob Hess, March 31, 2008, April 28, 2008, May 5, 2008.

[34] The report from the Age indicated that ‘… there was an attendance of approximately 10,000’, with gate-takings of £325. Age, August 14, 1933.

[35] Emphasis in the original.

[36] The transcript is drawn from the voiceover at https://www.britishpathe.com/video/soccer-cricket-perhaps-but-rugby-well-girls. An exclamation mark, some other punctuation and the spelling of expressions such as ‘Whoa’, ‘Ahh’ and ‘Aha’ have been added at my discretion to reflect the tone of the narration. Some expressions by the commentator are also difficult to decipher. For example, there is reference to what sounds like ‘Carlton colleagues’ but it is more likely to be ‘Carlton Colleens’, given that a ‘colleen’ is ‘a young Irish girl’ (in Irish Gaelic, ‘a young unmarried woman’). See https://www.thefreedictionary.com/colleens (accessed November 4, 2018). The reference to ‘A perfect 36’ is likely a double entendre, referring to the total number of players on the field (18 per team) and the supposedly ‘ideal’ bust size (in inches) for a so-called ‘hourglass’ figure.

[37] Mike Huggins, ‘“And Now, Something for the Ladies”: Representations of Women’s Sport in Cinema Newsreels 1918-1939’, Women’s History Review 16, no. 5 (2007): 681.

[38] Ibid., 682.

[39] Ibid., 686.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Records indicate that a carnival day was scheduled at the Carlton ground ‘in aid of club funds’ during May 1935, but it is not clear if the scheduled women’s match actually took place. See the Argus (Melbourne), April 29, 1935. Given that Myra resided close to the ground it is very likely that if the 1935 game did occur she would have attended, if not participated.

[42] Age (Melbourne), August 14, 1933.

[43] For details of the 1947 series of women’s matches see Sinclair, “‘Who Won? Who Cares?’’’.

[44] Image from Leader (Melbourne), August 19, 1933

[45] Ibid.

[46] Pat Jarrett, ‘Football Too Hard for Women to Play’, Sporting Globe (Melbourne), July 26, 1933.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne), August 11, 1933.

[50] Ibid. Nott was subsequently named as the best player for Richmond following the match. Age (Melbourne), August 14, 1933. Significantly, a ‘D. Nott’ is listed among the members of the ‘Brymay [Bryant and May] Auxiliary’ who raised funds for a Homoeopathic Hospital in Melbourne. Herald (Melbourne), July 4, 1933.

[51] See Bulletin of Sport and Culture 25 (2006): 1.

[52] Martin Flanagan, ‘True Blue’, Age (Melbourne), March 21, 2007.

[53] Gary Tippet, ‘Women: The Once and Future Players’, Sunday Age (Melbourne), September 26, 2010.

[54] Lionel Frost, The Old Dark Navy Blues: A History of the Carlton Football Club (St Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1998).

[55] Tony de Bolfo, Out of the Blue: Defining Moments of the Carlton Football Club (Melbourne: Carlton Football Club, 2009), 66-67. In his later obituary for Myra, de Bolfo amends the date of the match to Saturday, August 12, 1933, and he mentions that Myra saw the film clip of the match at the Palace Theatre, Nicholson Street, North Fitzroy, on August 21, 1933. See Tony de Bolfo, ‘Carlton Trailblazer Myra Remembered’, http://www.carltonfc.com.au/news/2016-01-12/carlton-trailblazer-myra-remembered (accessed November 6, 2018).

[56] See Rob Hess, Matthew Nicholson, Bob Stewart and Gregory de Moore, A National Game: The History of Australian Rules Football (Camberwell: Penguin/Viking, 2008).

[57] See Brunette Lenkić and Rob Hess, Play On! The Hidden History of Women’s Australian Rules Football (Richmond: Echo Publishing, 2016), 72-78.