Motorcycling is said to be one the favourite summer pastimes of professional footballers.

Sheffield Green’Un, 13 June, 1914.

More footballers than ever have been involved in motor smashes this summer.

Liverpool Echo, 27 July, 1929.

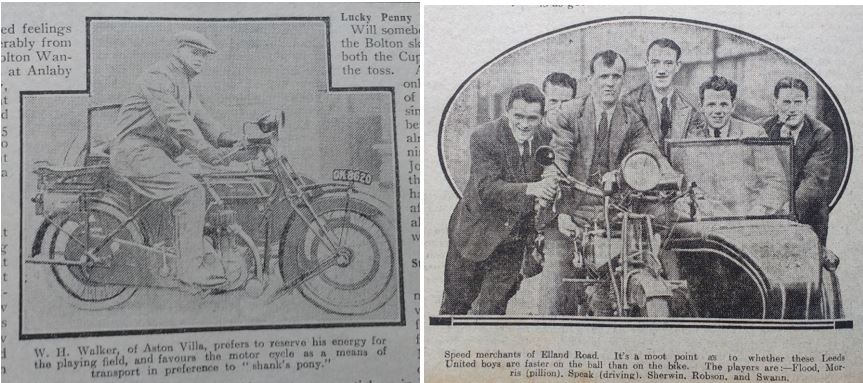

For many, the image of the male professional footballer away from the pitch is often associated with expensive and fast cars. A staple of media depictions since the 1960s, the origins of this love-affair with motoring can be traced back to the early 1900s. At this stage, the motorcar was still relatively new and expensive and only a few players like Robert Crompton of Blackburn Rovers owned one. More affordable and accessible was the motorcycle and by the 1910s they were growing in popularity amongst footballers who wished to participate in Britain’s emerging motoring culture. By the 1920s, popular papers like The Topical Times were including photos of players with their new status symbols.

The Topical Times captures the growing popularity of motorcycles in the early 1920s

6 January, 1924 and 29 September, 1923

Source: Author’s Own Collection

Access to motor ownership also meant risking Britain’s dangerous roads. Martin Pugh’s social history of inter-war Britain, We Danced All Night (2009), paints a frightening picture of the safety record of this developing motoring culture. During the early 1920s, fatal accidents ran at 2,500 per year and non-fatal ones at 62,000. In 1930 alone, 7,000 people were killed while 150,000 were injured, compared with respective figures of 3,221 and 31,130 in 2004. With a total of 120,000 dead and 1.5 million injured in the inter-war years, Pugh has compared these losses with those equivalent to a small war.[1] Amongst these were several footballers. While statistically small in number, they do provide an insight into the dangers of inter-war motoring, the types of dangers involved and how the media and clubs reacted to those risks.

Such accidents were beginning to occur prior to 1914. Perhaps the earliest recorded accident comes from 1913, when Jock Rutherford of Newcastle United and England collided with a car. He was thrown over the handles and hit the car’s lamp with his face.[2] The following year, Sheffield Wednesday’s new and expensive signing, the Scottish international James Blair, missed his club’s opening practise game after a ‘spill.’[3] In 1915 John Hampson of Leeds City skidded off the road. He and an accompanying friend got away with light injuries but his brother suffered a fractured leg.[4] None of these seemed to have stimulated any wider discussions about the dangers that motoring posed to either player or club.

The post-war period initially saw a continuation of these accidents and narrow scrapes. In 1922 John Hutton of Pittodrie and Andrew Lees of Aberdeen, suffered cuts and bruises when Hutton swerved to avoid a collision. The following year Colin Mackay of Bradford City escaped with a bruised shoulder when he collided with a motorcar, with his wife and mother-in-law escaping without harm.[5]

A fictional depiction of the violence of a motorcycle crash

The Boys’ Realm, 29 July, 1911

Source: Author’s Own Collection

The summer of 1924 brought home the potential lethality of the motorcycle crash. In June, Bradford City’s Joe Hargreaves overturned his bike and hit a wall with his head, suffering a fractured skull. He died in hospital two days later without regaining consciousness.[6] The following month Charles Redford of Manchester United was visiting his parents in Walsall when he swerved and skidded off the road and into an electric mains box. While a female passenger on pillion suffered only light injuries, Radford received ‘terrible’ injuries to his face and jaw and died shortly after arriving in hospital. He had established himself in the first team and was described as a 26-year-old player with ‘a bright future.’[7]

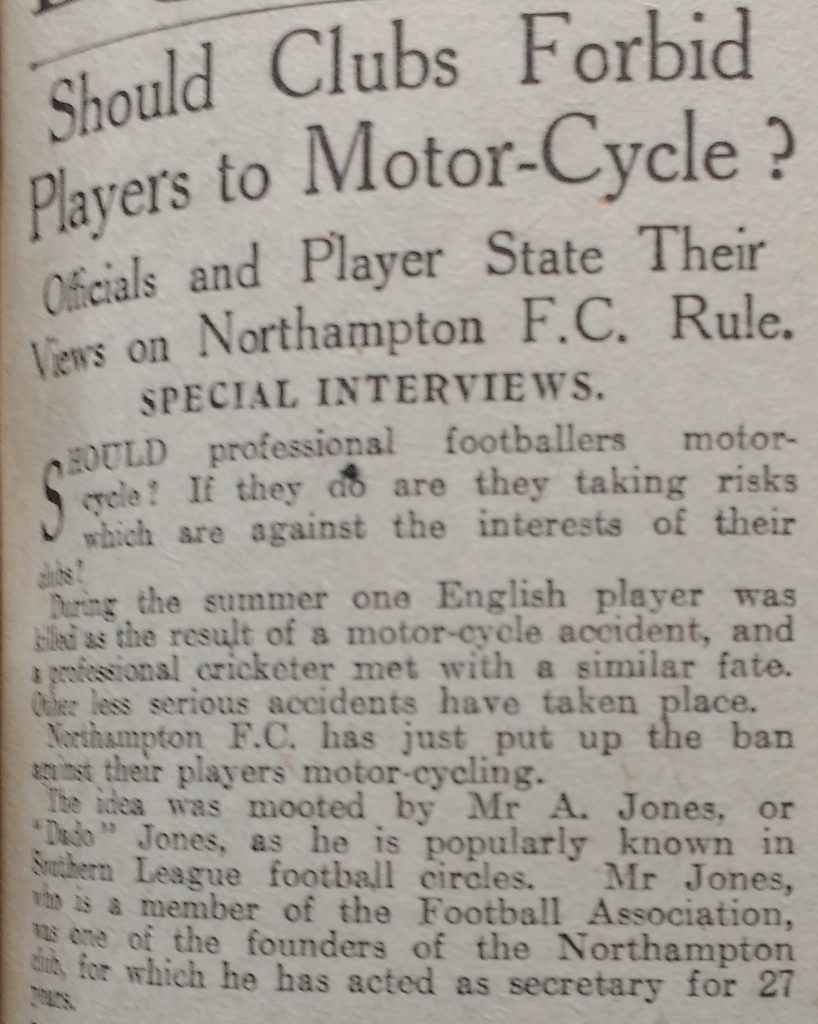

The lethal nature of these accidents caused some officials to reconsider whether players should be allowed such a dangerous hobby. In August 1924 The Topical Times covered Northampton Town’s newly introduced ban on players driving motorcycles. It interviewed both Mr A. Jones, who had introduced the ban as Northampton’s secretary, and several players from other clubs to ascertain their views. Mr Jones explained that the matter had been in his mind for some time, especially with the previous deaths of three professional county cricketers but that the death of Redford had led him to take action, especially as he was aware of three or four Northampton players who had motorcycles. Explaining that while he did not wish to sound ‘mercenary’, clubs did need to consider protecting players as financial assets, especially smaller ones who needed player sales to stay afloat. He also stated that, ‘I do not for a moment suggest that any of our motorcyclists are reckless riders’ but he was thinking of the ‘risks’ caused by ‘heavy traffic on the roads and in the street.’[8] The Topical Times also solicited the views of John Chapman, the Manchester United manager, “My opinion of motorcycles as a means of eating the miles and making others eat their dust will not bear publication, and I endorse in every respect Northampton’s rule.”[9]

he Topical Times gave a platform to those club officials who questioned the safety of riding motorcycles

23 August, 1924.

Source: Author’s Own Collection

In contrast, Joe Smith of Bolton Wanderers made the case for the player’s freedom in choosing his leisure activities.

I don’t see the club has any right in the matter…after all, if a player does his proper amount of training and plays his best for the club that is all he is supposed to do….motorcycling is a healthy recreation and it is not likely that a footballer will take risks more than the ordinary risks when he is riding.

I am not a motorcyclist, but I know many players who are, and they are not any more likely to be injured than other people. If they motorcycle in their own time I don’t see that the club has anything to do with the matter at all.[10]

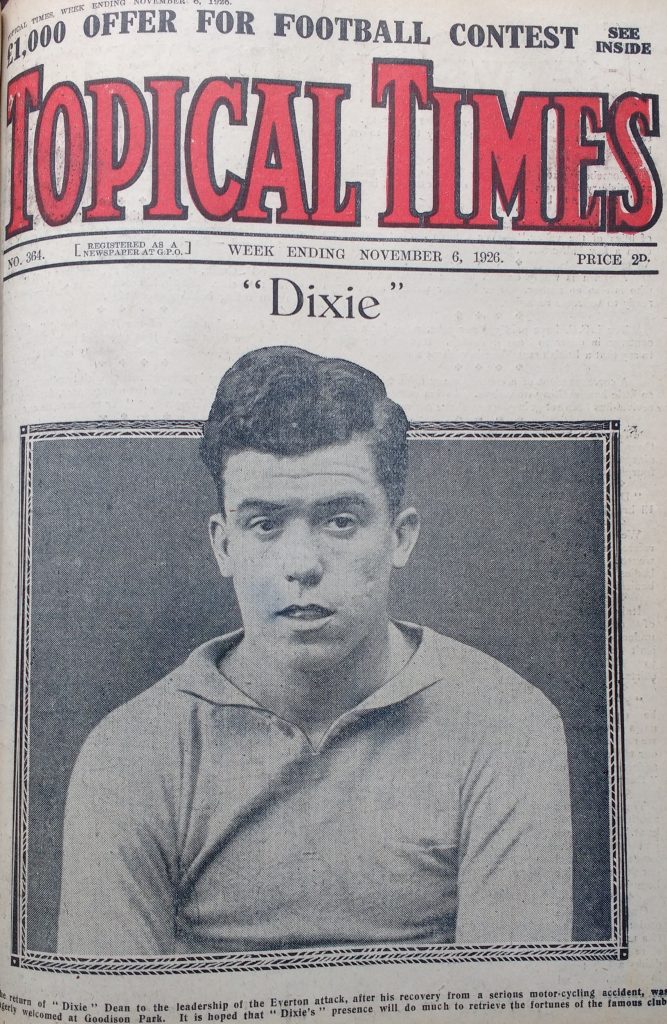

What Smith failed to discuss was whether potential accidents that threatened a player’s career were worth the risk. Things may well have turned out very differently for one of the most famous names in English football history. In 1925, Everton spent £3,000 on an 18-year-old prodigy from Tranmere called Dixie Dean. A year later Dean had scored 32 goals in his debut season in the First Division. In the summer of 1926 Dean sought to relax by motorcycling to play tennis. While taking a female friend to a game, his motorcycle was hit head-on by a motorcycle combination. Dean was taken to hospital with his jaw broken in two places and a suspected fracture of the skull. Unconscious for 36 hours, it took over a week before he could be moved from a local hospital to one in Liverpool which had an X-ray machine.[11] Despite the club doctor pronouncing that his career was over, by October 1926 Dean was back playing for Everton, an event celebrated by The Topical Times.

The Topical Times celebrates the return of “Dixie” Dean to playing for Everton after recovering from a motorcycle crash

6 November, 1926.

Source: Author’s Own Collection

Dean’s accident produced similar articles and comments in The Topical Times to those produced in 1924. Football League administrator Charles Sutcliffe argued that clubs should put bans on motorcycles in contracts, while players should accept any reduction in their personal liberty in order to protect the club financially.[12] The Everton Minute Books show that the directors agreed shortly after Dean’s crash that players should be forbidden from riding motorcycles. The following year a formal clause was inserted in the players’ contracts, banning them from owning motorcycles or indulging in any activity that might incapacitate them.[13] Interestingly, Nick Walsh’s biography of Dixie Dean records that on his return from hospital Dean sought out and rode a motorcycle in order to re-establish his confidence. At other clubs, such behaviour was beginning to be regarded as provocative. Another piece in The Topical Times highlighted that one director felt that any player who drove a motorcar or motorcycle should indemnify the club against any loss and should not expect to receive any wages if they were injured.[14]

The Topical Times provides a platform for views hostile to players owning or driving a motorcycle or motorcar

Source: Author’s Own Collection

While Dixie Dean regained his form and place in the Everton team, it was not the same for Harry Chambers of Liverpool and England. In November 1927 he lost a claim for damages against the car driver who had knocked him from his motorcycle. Chambers argued that he had lost form following the accident and after seven games had been dropped from the first team. The examining doctor felt he could not discover anything wrong and thought the loss of form, ‘may be due to anxiety over the result of the accident.’[15] At the end of the season Chambers was allowed to join West Bromwich Albion. While he was now 32 years old, the loss of form due to the accident may also have played a role in the club’s decision to let him go.

Chambers was lucky to avoid serious harm but others were not so lucky. Another fatality occurred in March 1928 when George Turnbull of Bradford Park Avenue was killed. He had left his home in Cleakheaton to go for a midday Sunday drive but lost control, came off the road and hit his head against the road. He was found in an unconscious state and with a fracture at the base of his skull.[16] Within a month the club had banned its players from driving motorcycles. In a somewhat blunt interview with a reporter the club chairman, Mr S. Waddilove, explained that:

The death of George Turnbull not only lost us a good player – a man liked by everyone – but it cost us money. Our attitude, therefore, is simply to protect the club’s interests and the investor’s money. We felt bound to do it.[17]

The message was reinforced by the club secretary announcing that the club would fine any player violating the rules. The newspaper article also noted that the club had paid a substantial transfer fee for Turnbull while, ‘For the sake of his widow, the club has borne certain expenses incurred by his death.’ A benefit game with West Ham was arranged, with some 6,000 fans attending.[18]

If the dangers of driving were not already apparent, there could be no doubting them in 1929, with two serious accidents and two fatalities. Charlie Fox of Fulham escaped injury when his bike skidded off the road. However, his sister Bessie on the pillion seat was taken to hospital with severe concussion and a suspected fractured skull.[19] In the same year William Gibb of Arbroath was hit by a bus. His pillion passenger somehow escaped unhurt but Gibb was thrown over a wall into which the bus crashed. Its wheels pinned slabs of the wall on his legs and presumably Gibb must have waited in agony some time until the bus could be jacked up to release him. He was taken to hospital with fractured legs and other injuries.[20] Gibb survived but William Hunt, a goalkeeper with Coventry City, was killed when knocked from his motorcycle by a car. Finally, Everton may have banned their players from riding motorcycles but not their staff. Assistant trainer Bertram Smith was also killed when the back-tyre of his motorcycle came loose, sending him into a telegraph pole. The Everton directors gave £25 to his widow.

The reoccurrence of such incidents may have helped encourage other clubs to introduce bans on motorcycles in the 1930s. Matthew Taylor has noted such bans at West Ham United, Brentford and Huddersfield Town and these might account for the lack of newspaper mentions of accidents after 1929.[21] Perhaps players were also beginning to favour the motorcar over the motorcycle as a safer means of transport.

Article © of Alex Jackson

References

[1] Martin Pugh, We Danced All Night: A Social History of Britain between the Wars (London: Vintage Publishing, 2009), p.246.

[2] Sheffield Green’Un, 2 October, 1913.

[3] Ibid, 22 August, 1914.

[4] Birmingham Daily Post, 4 August, 1915.

[5] Aberdeen Press and Journal, 15 March, 1922 and Northampton Chronicle and Echo, 28 August, 1923.

[6] Leeds Mercury, 23 June, 1924.

[7] Yorkshire Post, 15 July, 1924.

[8] Topical Times, 23 August, 1924.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Nick Walsh, Dixie Dean: The Story of a Goal Scoring Legend (London: Pan Books, 1978), pp.76-77.

[12] Topical Times, 26 July, 1926.

[13] Everton Minute Books, 22 June, 1926 and 27 April, 1928. The Everton Collection.

[14] Topical Times, 25 December, 1926.

[15] Northern Whig, 8 November, 1927.

[16] Hull Daily Mail, 26 March, 1928.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Leeds Mercury, 26 April, 1926.

[19] Daily Herald, 22 June, 1929.

[20] Scotsman, 27 June, 1929.

[21] Matthew Taylor, The Leaguers: The Making of Professional Football in England, 1900-1939 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), p.137.

![“And Then We Were Boycotted” <br> New Discoveries About the Birth of Women’s Football in Italy [1933] <br> Part 3](https://www.playingpasts.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Marco-Giani-Boycotted-Part-3-440x264.jpg)