From the Victorian age to the World War Two, the Boys’ Story press provided the bulk of reading for British boys, both young and old. Many of these publications began life as ‘Penny Dreadful’s’ during the Victorian period and were filled with tales of crime and detectives, but some evolved to include stories of adventure and glory, of which sport became a prominent theme. Reflecting the national interest in the sports of soccer, rugby and cricket these sports dominated these fictional tales, although during events such as the 1908 London Olympics there were often dedicated stories or series’.

Although historians have investigated perceptions of war and manliness through the boys’ story, examination from a sporting perspective is limited, excluding the excellent works by Alexander Jackson, Jeffrey Hill and Mike Huggins. The Boys’ story has plenty to offer the sports historian as they have the potential to give insight into British sporting, culture, attitudes and identity at their time of publication. As historian Kelly Boyd states; ‘they were quick to respond to the events of the day’ and ‘their popular characters to take part in important moments in society’, a theme certainly evident within the story focused upon here.

These stories of course have their weaknesses, particularly as the tales were produced by a small number of authors who were from a distinctly middle-class background and consequently their views might not be reflective of all of society. Jackson believes that the readership also came from the middle and upper-classes; boys who became the men of Empire. Even considering these weaknesses many stories have the potential to offer insight and intrigue that is useful to any historian examining the development of British sporting philosophy. These publications certainly had the potential to influence young men across the country. The focus here will be upon ‘The Boys’ Realm’, a publication which in 1906 boasted it was producing 200,000 copies for a forthcoming issue, an impressive figure even if it had been slightly inflated by the editor.

A prime example of this came from ‘Tales of the Stadium’, a series of thirteen short stories that were published between May and August 1908. This series focused upon the events of the 1908 London Olympic Games that were taking place at the same time. Within there were stories about issues such as the sporting rivalry with the United States, the Marathon race, Field Events and the developing political and military hostility between Britain and Germany. All the stories followed an identical path, the British hero faced a struggle and moral dilemma, before doing the right thing and winning a gold medal for his country against all odds.

Here, the focus will be focus upon the second story from this series; ‘An Affair of Honour’, written by Andrew Gray. This tale describes the rivalry between a British and German officer who were both to due compete in the fencing event at the 1908 Olympics. Throughout British ideals and honour are portrayed, as is an apparent lack of German honour. Ultimately British superiority is demonstrated through the values of the gentleman amateur, a figure which all young men of Edwardian Britain should seemingly seek to emulate.

The anti-German rhetoric was certainly not uncommon at this time, as through the combination of the signing of Entente Cordiale with traditional enemy France in 1904, and rising German militarism in the early twentieth century ensured that it was always Germany who were portrayed as the enemy. Historian Matthew Paris argues that at this time; ‘many writers of juvenile fiction had begun to subscribe to the idea that Germany was actively working to undermine British power’, something certainly evident within the contemporary novels; ‘The Riddle of the Sands’ (1903) and ‘The Invasion of 1910’ (1906) and frequently within the boys’ stories.

‘An Affair of Honour’ began at a music hall in Belgium, where British officer and fencer; Tubby Crosthwaite was enjoying an evening with friends, something that changed when a group of German officers, headed by ‘Major Von Schlag’ entered. Tension began when the Germans expected to be greeted with a salute from Tubby and his colleagues, something our hero felt wasn’t necessary as ‘the officer, he perceived, was merely a major and not the Emperor himself, therefore he saw no reason why he should vacate a comfortable seat to bow down and worship’.

Tensions continued to grow between the two groups when ‘filthy’ looks being exchanged across the hall, before things turned sour after the Germans began to sing songs about Britain; vilifying her and commenting on the nation as fools. Such songs are explained to be common on the Continent at this period, primarily regarding the British performance during the Boer War. Tubby is shown to be a good sport at first-illustrated here as a fine British trait, but the mockery gets to the point where he cannot take the insults anymore and he rises from his seat, provoking the German to do the same, concluding the first chapter.

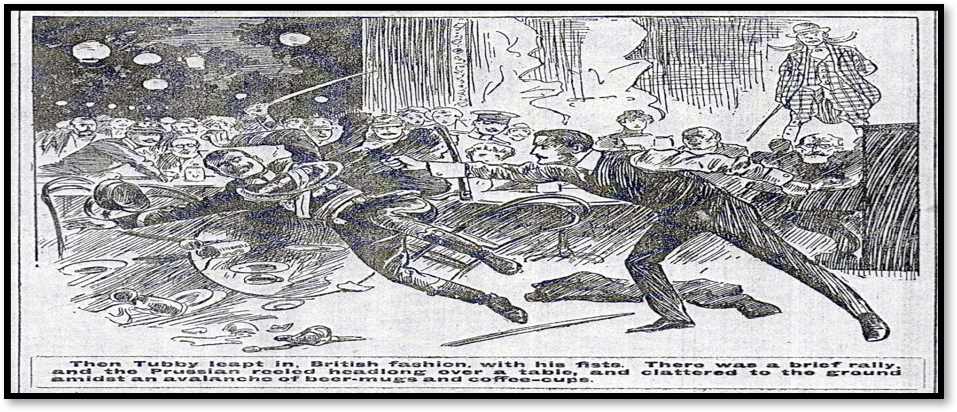

The second of three chapters began with a description of how Von Schlag drew his sword upon Tubby, something he found incomprehensible because he only had his stick for his defence. A scuffle ensued between the two men and it is described that Tubby was only able to escape with his life after he ‘leapt in British Fashion, with his fists’ giving the German several blows to his mouth (as demonstrated by the illustration). Tubby left for home the next morning but he didn’t depart without placing a note underneath Von Schlag’s door at the hotel, saying that if he is ever in London, he should look him up.

The brawl between the two men is an obvious attempt to show the German’s as being ungentlemanly and certainly inferior to the British, a theme which continued in the final chapter entitled ‘Major Von Schlag meets his Waterloo – How Tubby fought for Britain’. The chapter took up the story the evening before the Fencing competition at the Savoy Hotel, where the two men acknowledged each other and Van Schlag challenges Tubby to a duel, which he accepted.

Although by accepting the duel Tubby didn’t cover himself in glory, his actions during and after the duel do. Tubby wins the duel and he does so by disabling Von Schlag’s arm and not by killing him, (which the author suggests would have been the case had the roles been reversed) and then by letting him receive medical attention first.

Bleeding, but relatively unhurt, Tubby then made a quick exit so he could make the start of the Olympic fencing competition. The story concluded with how Tubby got on and the excuse Von Schlag gave for not competing:

‘Tubby fought for Britain that summer’s day and fought so well that no one could possibly have guessed that only an hour or two before he had been fighting for his life, or that his pipeclayed jacket hid a bloodstained bandage.

As for Von Schlag, it was announced that he had dislocated his wrist, and his place in their team was taken by a reserve.

It was said of the missing major that he was far and away the best man of the German team, and that if he had been able to compete the result might have been different. Indeed, it was hinted openly that there was not a swordsman on the British side who could hold a candle to him.

There were one or two who knew different, however, and chief of these was Tubby’.

This final line yet goes further to demonstrate the sense of the hero, Tubby being a British gentleman. On the other hand, the German; Von Schlag is shown throughout as being ungentlemanly and unsporting, a simple message, but typical of these stories. Aside from the anti-German bias here, this story demonstrates the importance of being a good sport, keeping to the rules (even in a bar room scuffle) and putting others before yourself. These morals were put into question during the 1908 Olympics, but at least in the eyes of the fictional boys’ press the British were always the true gentleman and figures which young British men should aspire to become.

Article © Luke J Harris