Rethinking the 1895 split

PART TWO

The decision to secede

The history of the two senior Bradford clubs is a case study in democracy and decision-making within nineteenth century sports organisations. Although the football publicans had no personal requirement for broken-time payments they became an influential lobbying group in favour of Bradford FC and Manningham FC joining the breakaway Northern Union and seceding from the Rugby Union.

The football pubs allowed player celebrities the chance to command a personal following to secure influence within their clubs whose decision-making was determined by the one member, one vote member organisation structures. Yet what concerned them was not broken-time per se as opposed to the concern that their clubs might be left behind by others forming a rebel league. Their stance was partisan in nature, to ensure that their clubs would play in any elite northern competition and maintain parity.

Although Bradford FC in particular arranged fixtures with leading southern and Welsh clubs, subsequent to the launch of the Yorkshire Senior Competition in 1892, it was league fixtures that drew the biggest crowds. Although value was attached to international selection and the status derived from membership of the RFU, there was a growing irritation and contrariness among members of the senior Yorkshire clubs towards increasingly antagonistic attitudes that were building in the south. Maybe a fin de siecle mood encouraged thought of radical change with the example of the northern based Football League providing the inspiration for a northern rugby union.

In the case of Bradford FC, the commitment to the Northern Union was very much at the stroke of midnight. The club’s leadership agonised over the financial implications and in the final event it was popular opinion – and the influence of the footballer pubs – that probably swung the decision. Members of the club’s committee had grave misgivings about joining the breakaway competition and subsequent events surely vindicated their concerns.

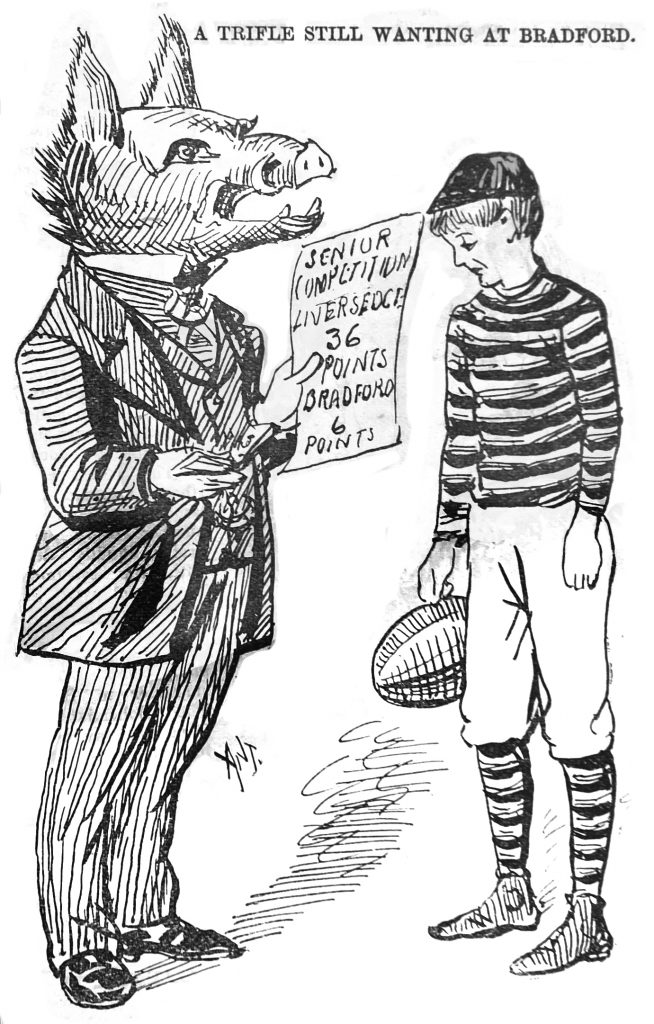

- Bradford Cartoon 8th June 1893

Opposition within the club to the proposed Northern Union was not an issue of class politics, nor was it necessarily based on affection for the Rugby Union – the concern was that the new body was a rushed affair and too narrow in its composition. Crucially the Bradford leadership favoured a broad based northern union and not simply a league. The Park Avenue committee also knew that a breakaway would not be universally popular. In 1896 it was reported that Bradford FC suffered a sizeable reduction in membership and a likely reason for this is that these people valued the club’s status in the rugby world and its ability to stage prestige fixtures with touring sides. The loss of such fixtures removed an important differentiator with Manningham FC and henceforth, rugby followers would pick and choose between games against the same (northern) opposition at either Park Avenue or Valley Parade.

The future of Manningham FC had been safeguarded by membership of the Yorkshire Senior Competition and its leadership committee knew that the club could not afford to be left out of a new Northern Union. The new competition also ensured equality with Bradford FC and helped safeguard the future of Manningham FC. The decision to secede from the Rugby Union was thus based on practical, economic grounds rather than ideological. The consensus among the northern rebels was that it was impossible to remain a member of the RFU with the likelihood of falling foul of stringent anti-professionalism regulations. The Manningham officials knew that their club was in the firing line given that in December, 1894 it had been singled out at an RFU meeting and implicitly accused of professionalism on account of a trip to Paris (where Manningham FC had played Stade de Francais).

- BCA & FC Crest

- Manningham FC monogram

The belief in Bradford was that the southern establishment was standing in the way of progress and that change was unavoidable. On its part the Manningham FC committee was reconciled to the breakaway in the belief that any split would not be permanent and that the RFU would eventually come to its senses. The belief among northern clubs that this might be the case could explain why the Rugby Union was particularly dogmatic, as if to demonstrate that there would be no compromise over professionalism in rugby.

Our knowledge of what happened during the summer of 1895 is likely to remain incomplete. Many of the meetings were conducted in secret, in smoke-filled rooms and my sense is that many of the newspaper reports were speculative in their content. There is also the suggestion that club jealousies encouraged the spread of false information. The football pubs in Bradford assumed importance as a source of news and rumour and I believe it safe to conclude that many opinions were formed from incomplete information.

The Rugby Union out-manoeuvred the rebel clubs but the tactical failure of the latter had more to do with the fact that they were far from united. Historic jealousies among the northern clubs undermined mutual trust and the Bradford FC leadership committee for example resented that the initiative was driven by clubs with lesser pedigree than itself, with less at stake financially and specifically without the same debt commitments. Similarly, populism would have forced the negotiating position of individual club representatives. As a collective body, it was too much to expect that the northern clubs could have matched the political initiative of the RFU leadership in what became a high stakes contest. The likes of William Cail and William Carpmael, acting on behalf of the RFU, calculated that they held the advantage in the game of poker due to divisions not only between the senior northern clubs, but also from antagonisms that existed between them and the junior clubs – for example arising from denial of promotion to the Yorkshire Senior Competition which was an emotive issue in the 1895 close season.

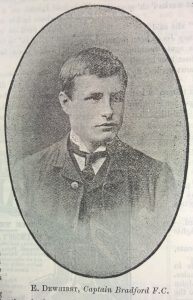

- Edgar Dewhirst BFC captain 1895

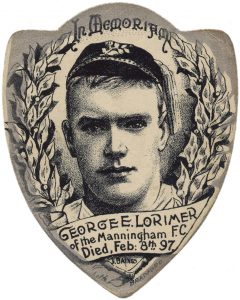

- George Lorimer Manningham FC

An industry restructuring

It is important to recognise the connection in Yorkshire between the promotion issue and broken-time in the events of 1895. What they had in common was that they were both key drivers of the profitability of the senior clubs – the first being the protection of income (through regulating membership of the YSC to bigger clubs capable of attracting good crowds); the second being the control of wages and, crucially also a safeguard against full professionalism (and the risk of wages being increased to the level paid by soccer clubs). Contrary to what has been claimed, the new Northern Union was not universally acclaimed in the north and in Yorkshire it aroused considerable animosity among the junior clubs who saw it as a cartel, contrary to their interests. In this sense, it was yet another instance of senior clubs promoting monopoly competition and excluding smaller rivals. Again, in 1901, a subsequent restructure of the Northern Union was interpreted as a further example of large clubs instinctively protecting their self-interest at the expense of others.

The formation of the Northern Union (NRU) disturbed the equilibrium that had emerged after the formation of rugby leagues in 1892. The hierarchy of clubs served as a food chain whereby local sides existed as feeders to junior and senior organisations. Once the RFU forbade relations between its members and the rebels, that delicate chain was broken. Perhaps not surprisingly it was the smallest clubs in Yorkshire who next joined the NRU, seceding twelve months after the original schism. The junior – or medium-sized – clubs held back as long as possible and even enjoyed a temporary new lease of life, until financial necessity forced them to switch as a means of self-preservation because rugby union in Yorkshire lost critical mass.

What has been overlooked is that, in Yorkshire at least, the body of the Northern Union was hollowed-out in the shape of an egg-timer with senior clubs at the top and local clubs at the bottom. The absence of numerous medium-sized, junior clubs denied the NRU a pyramid structure. The reason that most of the former junior clubs did not join the Northern Union, or were members for only a couple of years, was that they succumbed to financial failure. The mass insolvency of these clubs in the 1890s was thus the equal and opposite to what had happened in the first half of the 1880s when they had mushroomed. In this regard the NRU was not a cause of their failure but the schism of 1895 certainly hastened their disappearance. By the 1890s the finances of the smaller clubs were already precarious and this had a lot to do with the impulsive enthusiasm and naivety behind their emergence in the previous decade – which in the Bradford district came from the excitement of the Yorkshire Challenge Cup. In West Yorkshire their space came to be filled by soccer and in Bradford, sports fields were lost to rugby.

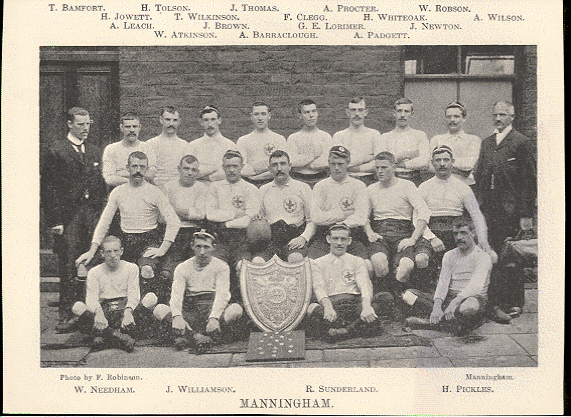

- Manningham NU Champions 1895-96

By the 1890s the Yorkshire rugby industry was characterised by over-supply and in this context, the formation of the Northern Union in 1895 occasioned an industry restructuring. (It could even be argued that the defence of amateurism by the RFU was an equivalent economic strategy to control competition.) With regards to the Northern Union, parallels could be made with what happened in soccer such as the launch of the Premier League in 1992 or in northern rugby, the Super League in 1996. First and foremost, it was about optimising profitability for the members – these were all examples of naked sports capitalism just as the formation of the Yorkshire Senior Competition league in 1892 had been. Subsequent to 1895, the changes to the Northern Union – professionalism, rule changes and thirteen aside – were driven by commercial criteria to attract crowds as the sport came under increasing competition from soccer. The need for change is evident from analysis of gate receipts at Valley Parade (home of Manningham FC) and at Park Avenue (Bradford FC) with a plateauing of aggregate revenues after 1892 and – on the basis that more games were being played – a drop in average attendances. It was the decline in profitability that ultimately led to the eventual abandonment of rugby at Valley Parade and Park Avenue in 1903 and 1907 respectively. There is no other town in England in which two leading sports clubs have switched codes on two separate occasions.

Article © John Dewhirst

Links to the other articles in this series –

Rethinking 1895 – A Bradford Perspective – Part 1 – https://goo.gl/gojusg

Rethinking 1895 – A Bradford Perspective: Part 3 – https://goo.gl/6jZZc2

John Dewhirst is author of ROOM AT THE TOP, A History of the Origins of Professional Football in Bradford and the rivalry or Bradford FC and Manningham FC (Bantamspast, 2016) and LIFE AT THE TOP, The rivalry of Manningham FC and Bradford FC and their Conversion from Rugby to Soccer (Bantamspast, 2016). Refer www.johndewhirst.wordpress.com for details.