On August Bank Holiday Monday each year at around 4pm, the usually calm River Windrush , which runs through the centre of Bourton on the Water, in Gloucestershire, is invaded by two teams of players from Bourton Rovers FC. They are battling it out for victory in the ‘Annual River Match ‘, which like many traditional ‘Mob Football’ matches of the past, is always played on or around a Holy day or Bank holiday and brings the whole community together

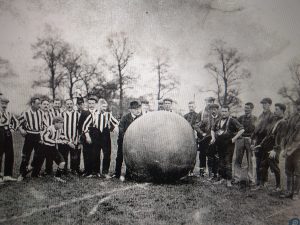

The Bourton River Match circa 1920’s

Traditionally in the past, ‘football’ matches tended to be played at ‘Shrovetide’, which is around Shrove Tuesday in February and it is thought that it was an opportunity for a ‘last round of merrymaking before the sombre season of Lent’. This match doesn’t fit that profile, but it could be viewed as a celebration of the last Bank Holiday before Christmas.

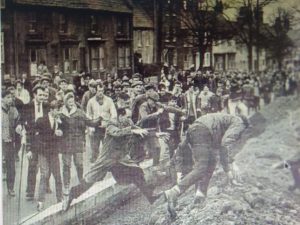

The tradition at Bourton dates back to the early 1920’s ( no one is quite sure when it actually began) and attracts hundreds of spectators who converge on the banks of The Windrush and goal posts are set up in the river with ‘the pitch’ approximately 50 metres long and 9 metres wide. The match normally lasts around 40 minutes depending upon the temperature of the water and is usually six a side.

A spokesperson from the club explained:

The game has been played for over 100 years and rumour has it that it was started by a group of men, who to relieve their boredom, jumped into the river and had a kick a round.

This match now coincides with the village fete and is regarded as a ‘typically quirky British event’, by foreign visitors. They often get TV companies from around the world and even TV personality Griff Rhys Jones turned up in 2015 and was yellow carded for diving. Bearing in mind that Bourton on the Water, is known to many as, ‘The Venice of the Cotswolds’ famed for its five stone bridges that span the river dating from 1654 to 1911, it is not surprising that they should invent a game that is played in the river!

The only surprising aspect of this game is that it took them so long to invent it.

The match in more recent times

Association Football as it is known today, was born out of these medieval contests and was eventually codified in 1863 largely due to the ex-public school and university players involved in the game, wanting to standardise the rules and split from ‘Rugby football’ in the early 1870’s. Different forms of the game were then established in Australia( AFL) , America ( NFL) and Ireland ( Gaelic Football).

However, amid these different developments in the ‘football world’, several different traditional ‘foote balle’ games, dating back centuries and sometimes referred to as ‘Folk’, ‘Shrovetide’ or ‘Mob’, still continue in many parts of Britain today and are usually played between neighbouring towns, villages and parishes, often involving an unlimited number of players across an unlimited area. These ‘games’ give a unique insight into how the game we know today developed.

At Alnwick in Northumberland, ‘Scoring the Hales’, is a large scale Shrovetide Football match and begins with the Duke of Northumberland dropping a ball from the battlements of the castle. First played in 1762 between two local parishes, it still exists today and can often have up to 150 people taking part! The winner is the team who scores two ‘hales’ or goals at their opponents ‘end’.

‘Scoring The Hales’ at Alnwick Northumberland

Likewise, Ashbourne in Derbyshire, ‘The Royal Shrovetide Football Match’, which is played annually on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday each year, was first played around 1667 and was originally known as ‘hugball’ and there are suggestions that the original ‘ball’, was a severed head that was thrown into the crowd after an execution and the ball was carried or ‘hugged’ .

The ‘Atherstone Ball Game’, in Warwickshire is another that is played on Shrove Tuesday each year and honours a match first played in 1199 between Leicestershire and Warwickshire, when teams reputedly used a bag of gold as the ball.

The Atherstone Ball game in 1905

In County Durham, ‘The Sedgefield Ball Game’ is still played on Shrove Tuesday and many believe that the tradition dates back over a thousand years and in

Haxey in North Lincolnshire, ‘The Haxey Hood’ has been played on January 6th( 12th day of Christmas) since around 1752 and consists of a game in which a large ‘scrum’ pushes a leather tube or ‘the hood’ to one of four pubs in the town, where it stays until the following year.

Sedgefield Ball Game 1967

‘Bottle Kicking’ in Hallaton in Leicestershire still takes place every Easter Monday between the villages of Hallaton and Medbourne and is played across a pitch which is approximately one mile long. Originating in the late 18th century, the object of the exercise is to move a beer barrel known as a bottle, across the opposing teams stream.

More recently in Workington West Cumbria, ‘The Uppies and Downies Match’ began in the late 19th century, with the goals over a mile apart at opposite ends of the town and is traditionally played at Easter.

Hallaton Bottle -kicking Parade circa 2015

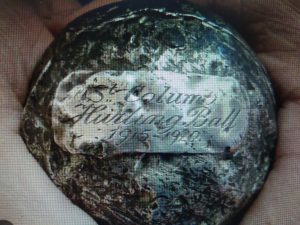

In the South West, ‘Cornish Hurling’( no relation to the Irish version) still takes place in two communities where matches are played on Shrove Tuesday and in the following week and dates back to the 16th century. In the town of Columb St Major in Cornwall, the contest still takes place in the town centre, as many of these ancient contests did, where shops are boarded up and a new ‘silver ball’ is produced each year for The Town v Country competition, which can by all accounts, be brutal.

The St Columb Major Silver Hurling Ball

The origins of these matches can be traced back to medieval times, where versions of ‘mob football’ would be played on holy days in the streets and fields around towns and villages the length and breadth of the British Isles and many of the rules are evident in the sport we know today.

In the Scottish Borders a ‘match’ is still played on the Monday before Shrove Tuesday every year at Hobkirk and is one of many ‘Ba games’ or Ball games found North of the border. Duns in Berwickshire has another form of ‘Handba’ and forms part of a summer festival in the town where the married men take on the bachelors, with goals set up at opposite ends of the town.

In Jedburgh, the ‘Jethart Ba game’ ceased to be a mass football match and became the game now played in the town in 1706 and is still played on the Thursday after Shrove Tuesday with a ‘callants’ or boys match followed by a men’s match. There are no boundaries, so the game is often played in the town centre with ‘goals’ at either end of the Market Square, which can prove difficult for shoppers. The teams are chosen based on where participants live, with ‘The Uppies’ born to the south and ‘The Doonies’ to the north of the Market Cross. Several balls can be thrown and the games can go on for hours.

Jedburgh Hand Ba game circa 2000

In Ireland, ‘Caid’ ( named after the ball which was made from animal skin), dating back to medieval times, was especially popular in rural areas and took on two different forms; the ‘field game’ , where the object was to score through arch-like goals and the ‘cross country game’, which took up most of a Sunday, where the winner crossed their opponent’s parish boundary in order to score, which could involve hundreds of players.

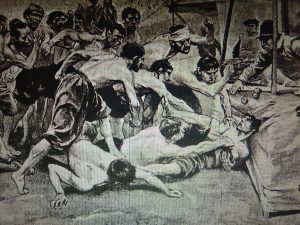

In Wales, ‘Canapan’ was a form of medieval football and was confined mainly to the western counties of Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire, but died out in the 19th century, when Rugby’s popularity started to grow. The game followed the traditional pattern of mob football, but the unusual aspect of the game was in relation to the wooden ball, which was usually soaked in animal fat or any other available lubricant; this made the ball extremely slippery and therefore more unpredictable.The game was revived in Newport Pembrokeshire, in the mid 1980’s, where two parishes competed for ‘The Cnapan Trophy’, but was abandoned ten years later when the organisers could no longer obtain insurance cover for player.

Canapan circa 1890’s

These games were violent, much more like Rugby in many respects and the fact that the games were often referred to as ‘mob’, probably gives a good idea of how they might have appeared to observers. In fact, the violent nature of these games led to them being banned by King Edward II in 1314 for around 350 years, until it was officially allowed ( many games continued to be played illegally and Henry VIII reputedly owned the first recorded pair of football boots) to be played again in 1667, during the reign of Charles II, even though Oliver Cromwell, who had played a form of football at Oxford reinforced the ban in 1653 when he became Lord Protectorate.

Although there are many descriptions of different forms of the game taking place across the country during this period, interestingly at Cawston in Nottinghamshire, between 1481 and 1500, there is an account of an exclusively ‘kicking game’ taking place with marked boundaries and there is also a reference to ‘dribbling’ and that throwing the ball in the air was not allowed.

The Cawston Football Game circa 1500 would probably have looked something like this

Football as we know it, was beginning to take shape.

Whilst the link between the game we know today and ‘mob football’, is quite incidental in many ways, it is recognisable with the fact that the game is still primarily about transferring an object( usually ball shaped) from one end of a playing area to the other where your ‘goal’ is to invade and score in or across your opponents territory.

The other major link is its strong presence in Britain and Ireland, as the evolution of Football is now widely accepted as having taken place in these islands.

Over a period of around one thousand years, the game has developed from a ‘free for all violent kick-about’ that took place on holy days and holidays, to being the highly structured global phenomenon that we see today.

Article copyright of Bill Williams