To read Part 1- click HERE , To read Part 2 – click HERE , To read Part 3 – click HERE To read Part 4 – click HERE

With the end of Clarice’s military career, we revert to glimpsing her life through the details of her husband’s. In 1944 Edward had replaced the famous Major Frank Buckley at Wolverhampton Wanderers. He did so in the face of fierce competition with over 100 other applications. Speaking to a reporter, Edward explained that “I am most anxious to make my home at Wolverhampton and settle down there with my wife, who will join me as soon as the exigencies of the services will allow.”[1]

Edward Vizard occupies a place between arguably the two greatest Wolverhampton Wanderers managers, Major Frank Buckley and Stan Cullis. One contemporary observer was Percy M. Young, a musicologist, football historian, and Wolverhampton Wanderers fan. He wrote in The Wolves: The First Eighty Years (1959) that:

Vizard had many of the qualities for management, but, of a somewhat retiring disposition, he lacked the drive and palpable energy to which Wolves, both players and directors, had grown accustomed. His tenure of office was brief, but he creditably accomplished the hazardous operation of starting the post-war Wolves on their new course.[2]

Edward came very close to being remembered more fondly than this. In the first peacetime season of 1946/47, he took them to third place in the First Division, only a point behind champions Liverpool. That description barely does justice to how close the title race was. In their final game, Wolves played Liverpool at home, with a win guaranteeing Wolves the title, and a draw giving them decisive edge on goal average over fourth placed Stoke, who had a final game to play a few weeks later. Liverpool defended for most of the game but scored the two chances they had to lead 2-0 at half-time. The second came when Albert Stubbins outpaced the Wolves captain, Stan Cullis, who was playing his final game. Although Wolves pulled one back in the 65th minute, they were unable to find the equaliser they needed, defied by goalkeeper Cyril Sidlow, who had been signed for £4,000 from Wolves and who still resided there. Stoke failed to win their game in hand and Liverpool became the first post-war First Division Champions.[3]

Edward and Wolves were unable to build on this but still finished high up the table in fifth spot in the 1947/48 season. However, in June 1948 Edward resigned. The board’s statement to the press read:

A difference of opinion having arisen between the board and secretary-manager over the future policy of the club, Mr Vizard has tendered his resignation, which has been accepted with regret.[4]

Edward expanded only a little on this when he spoke to the press himself.

Mr. Vizard said “differences have existed for some time. I leave feeling that I have done well for the ‘Wolves in overcoming post-war difficulties and signing players, who will keep the club in a good position in the League for years to come.”[5]

Thanks to Peter Crump and Dave Jones of the Wolverhampton Wanderer’s Museum, we can see beyond the press statements and into the club’s minute books. The board seem to have decided on a change and were willing to offer Edward the not-insignificant sum of £1,000 to accompany his resignation. The Minutes also record that six months later the club sent a letter to Edward telling him to stay away from the ground, which suggests that he may have been tapping up Wolves players on behalf of another club.[6]

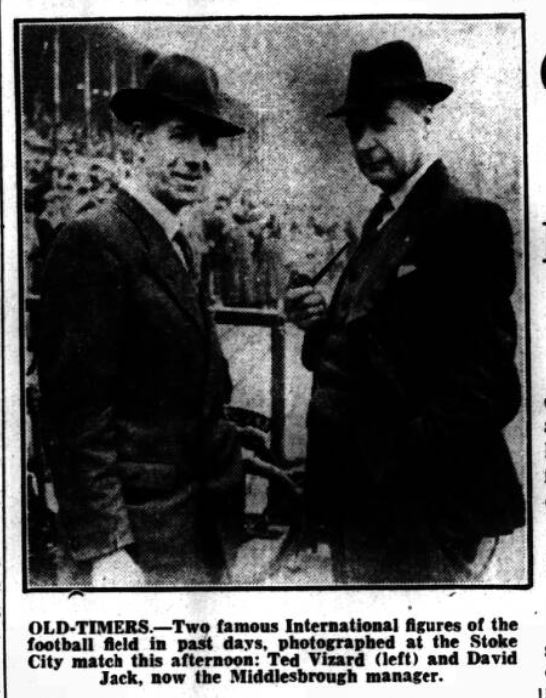

Image One: A few months after resigning at Wolves Edward catches up with his old teammate David Jack.

Staffordshire Sentinel, 18 September 1948.

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

For Edward and Clarice this resignation is a great “what if” moment. The man who took over at Wolves was Ted’s assistant. Stan Cullis would go on to become Wolves’ greatest ever manager, winning three First Division titles, two FA Cups, and leading them into European football. Perhaps, if the disagreement between Edward and the Board could have been resolved, we might be talking today about his triumphs at Wolves.

In the months afterwards Edward applied unsuccessfully for several managerial vacancies at Football League clubs.[7] In February 1949 his luck changed when he became the manager of Cradley Heath in the Birmingham League. Before the creation of the modern pyramid, regional leagues like this represented the highest level of football outside of the Football League. The appointment of Edward was a sign of the club’s ambitions, with one newspaper reporting that he was the highest paid manager outside of the Football League.[8]

The appointment seems to have been short lived though. The following month he was forced to deny newspaper reports linking him to the Bristol City post.[9] In June 1949, the Birmingham Daily Gazette reported that he was about to become the licensee of The Crown Hotel at Wergs. Edward denied that it meant the end of his managerial career, telling one reporter that “I intend to stay in the game as long as possible.”[10] When he left the club is uncertain but in 1950 there was no mention of Cradley Heath when Ted was linked to the vacant post at Bolton Wanderers. His outlook seems to have changed as he told a reporter that while he would consider any offer made by Bolton Wanderers ‘he was comfortable in his business, and it would take a very good offer for him to leave it.’[11]

Edward and Clarice had perhaps weighed up one last chance at the big-time against the benefits of secure employment. Edward was 61 when he took over The Crown and he would remain there for an impressive 21 years before he retired in January 1971. But while Edward was the official licensee, Clarice was equally involved in the day-to-day work. She certainly felt confident enough in this new role to speak publicly about it in 1954, when she argued for the importance of women in pubs at the annual rally of the Midland Women’s Auxiliaries of the licenced trade at Kettering. At the meeting she spoke in favour of the motion, “A man may be useful, but a woman is essential, in a pub.”[12] In 1953 the Vizards also started organizing an annual excursion to Ascot on Ladies Day and by 1965 it was attended by 64 people.[13]

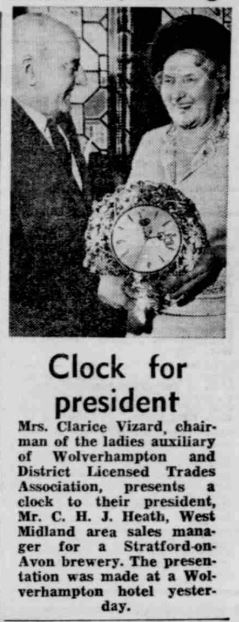

Image 2: Clarice in her role as Chairman of the Wolverhampton and District License Trade Association

Women’s Auxiliary Branch

Wolverhampton Star, 31 January 1969

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

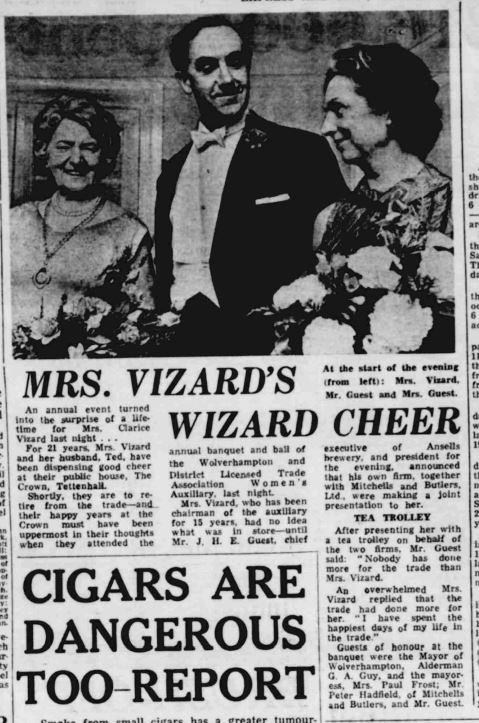

Given Clarice’s leadership experience, it is not surprising to find that in 1955 she became Chairman of the Wolverhampton and District Licensed Trade Association, Women’s Auxiliary. She held the post for fifteen years and honoured at the 1970 Annual Banquet and Ball with a surprise gift. Mr. Guest, the Chief Executive of Ansell’s Brewery announced that his firm and that of Mitchell’s and Butlers Ltd, were making a joint presentation to her.

After presenting her with a tea trolley on behalf of the two firms, Mr. Guest said: “Nobody has done more for the trade than Mrs. Vizard.”

An overwhelmed Mrs. Vizard replied that the trade had done more for her, “I have spent the happiest days of my life in the trade.”[14]

Image 3: Clarice is honoured for work in the Licensed Trade

Wolverhampton Star, 4 November 1970

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

In January 1971, Edward, now 82 years old, retired as the licensee of The Crown. The Wolverhampton Express and Star covered the presentation made on their final night, where the regular customers gave Edward and Clarice ‘a nest of tables and a cheque at a farewell party.’ Clarice explained that they would continue to stay in Wolverhampton, “We like living here…I suppose we shall use the crown as our local. We couldn’t think of going anywhere else.”

Image 4: Clarice and Edward celebrate their retirement

Wolverhampton Star, 8 January 1971

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive

Sadly though, Edward and Clarice did not have long to enjoy retirement together, with Ted dying on Christmas day 1973.[15] It seems Clarice had either moved to Bournemouth to be closer to her son George, or was possibly visiting him, when she died there in 1978, aged 83. George died in Pool-In-Wharfdale, Dorset, on 3 January 2002.[16] It is not known when or where Margaret died and whether her daughter Sally is still alive.

Conclusion

Researching the life story of Clarice Vizard has revealed a woman who deserves greater recognition on two fronts. Firstly, as one of the early female managers in English women’s football. Secondly, as a senior officer within the A.T.S. during the Second World War. Her life story is revealing though of how she moved through a variety of gendered environments. From her role as a “Hello Girl,” to women’s football, conservative politics, the British Army, and then world of pubs, she experienced and navigated her way through contemporary concerns, prejudices, and discrimination based on gender.

Her story is unusual, in that a large amount of evidence can be unearthed through digital sources. In the main part, this is due to her own abilities, rendering her visible through her political, military, and social activities. In addition, her husband’s own life was highly visible, providing useful contextual information. The challenge for historians is trying to assess how rare or unique she was as a female manager between 1917 and 1921. Equally important female managers may still be out there to be discovered, perhaps with equally rich life stories. For the moment though, I hope this series of articles will help raise interest and awareness of Clarice’s life and her contribution both to women’s football and Britain’s war effort during two World Wars.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Stephen Bolton for his generosity in sharing research on Bolton Ladies. Also, to Peter Crump and Dave Jones of the Wolverhampton Wanderers Museum, and the staff of the National Army Museum Templer Study Centre.

References/Sources

[1] Coventry Evening Telegraph, 6 April 1944.

[2] Percy M. Young, The Wolves: Their First Eighty Years (London: The Soccer Book Club, 1959), p.129.

[3] https://www.lfchistory.net/SeasonArchive/Game/2919 accessed 27.12.2024.

[4] Hull Daily Mail, 12 June 1948.

[5] Bolton Evening News, 12 June 1948.

[6] Wolverhampton Wanderers Club Minutes, 9 June 1948 and 5 January 1949. Provided by Peter Crump and Dave Jones from the Wolverhampton Wanderers Museum on 6.10.2023.

[7] Derby Daily Telegraph, 20 October 1948, and Yorkshire Post, 24 March 1949.

[8] Birmingham Daily Gazette,10 February 1949, Daily News, 5 February 1949.

[9] Western Daily Press, 25 March 1949.

[10] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 25 June 1949.

[11] Birmingham Daily Post, 30 October 1950.

[12] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 13 April 1954.

[13] Wolverhampton Express and Star, 17 June 1965.

[14] Wolverhampton Express and Star, 4 November 1970.

[15] Birmingham Daily Post, 9 January 1971, and 28 December 1973.

[16] England & Wales, Death Index, 1989-2023, accessed 23.12.2024.